|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

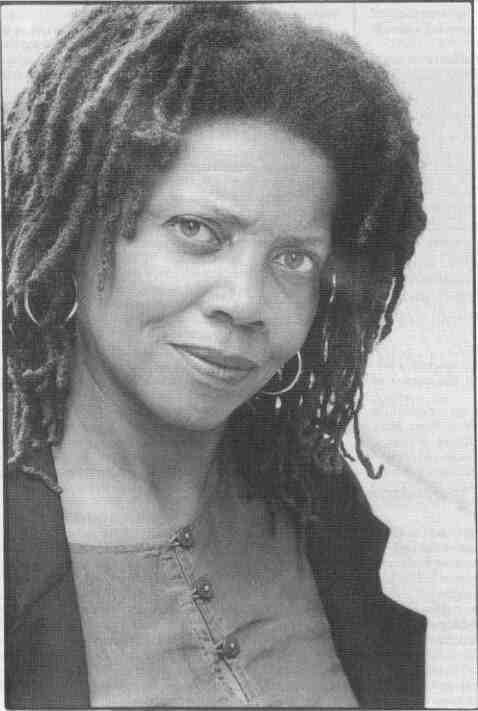

First Person by MARY A. MITCHELL Affirmative action cannot undo past racism, but it still serves as an equalizer to balance real discrimination  Mary A. Mitchell

Mary A. MitchellPhotograph by Jon Randolph If it were not for affirmative action, you probably wouldn't be reading this. At least not under my by line. I entered journalism through the doorway provided by an aggressive newspaper union that successfully bargained for a minority internship and scholarship program. I began my working career in the late '60s just as affirmative action programs were being introduced as a way to force the majority society to make room for its dark-skinned citizens. Back then, those of us who were stuck in urban ghettos and on the plantations in the South were supposed to benefit from a network of programs designed to guarantee fairness in housing, job opportunities and education, as well as protect our voting rights. But before that, when I was a legal secretary trying to make the most of a public education, I saw firsthand how utterly senseless it is to depend on others to be fair in a way that would bring about economic opportunities for non- whites. November 1995/ Illinois Issues/15 Despite the whining of those seeking to protect the ranks of white males — and charges that affirmative action programs have resulted in discrimination against their group — it is clear to me that such programs merely served to dislodge some of the stumbling blocks in the pathway of minorities. Even with such programs, many blacks gained only an entryway to professional achievement. Affirmative action did not provide the kind of inclusion needed for most to build a ladder from the ground floor to the upper suites. Traditionally, such inclusion has depended on nurturing and mentoring and, while preferential treatment allowed many of us inside, it did not and could not force disgruntled whites to take us under their wings.

Now, some 30 years later, opponents of affirmative action are seeking to dismantle the system based on misguided perceptions that blacks have gained ground at the expense of white males.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR While testifying recently before a committee considering a statewide ban on affirmative action programs, Rose Mary Bombela, the director of the Illinois Department of Human Rights, flat out refuted the white male discrimination myth. "[That myth] incorrectly assumes that each time a minority, female, or disabled individual is hired, the selection is made by passing over an equally or more qualified white male," Bombela said at the time. And according to statistics compiled by the NAACP in 1993, African Americans, who constitute 11 percent of the nation's total work force, account for less than 4 percent of workers in the highest paying professions, including lawyers and judges, dentists, doctors, industrial engineers and managers. While one can argue about the plight of the white male during the heyday of preferential programs, recorded evidence has clearly chronicled the sorry plight of African Americans without them. In 1963, those of us who lived in the Chicago Housing Authority's Ida B. Wells public housing developments on the Near South Side had a choice of attending Dunbar Vocational High School — a top-rated vocational school — and Phillips — a high school offering general education courses. Both were all black. Dunbar, however, was a few miles from the housing pro- jects and was located across the street from Prairie Shores — a private high-rise where doctors and professionals lived. They were mostly white people who worked at the nearby Michael Reese Hospital. I chose Dunbar because it meant that I got to get away from my neighborhood. And I would walk the three miles to school each morning, taking the path through Prairie Shores' private walkways, and imagine that I, too, was one of those successful professionals. It was a dream that was fostered by the countless novels that I curled up with in any comer I could find in our crowded four- bedroom apartment. The oldest of my mother's and father's 10 children, I often neglected my babysitting duties as I immersed myself in books about life beyond the housing projects. Because of my voracious appetite for the written word, by the time I had graduated grammar school, I was already scoring on the 12th grade level in reading. I began my working career in the late '60s just as affirmative action programs were being introduced as a way to force the majority society to make room for its dark-skinned citizens. Back then, those of us who were stuck in urban ghettos and on the plantations in the South were supposed to benefit from a network of programs designed to guarantee fairness in housing, job opportunities and education, as well as protect our voting rights. When I entered the job market soon after my high school graduation, I was equipped to compete for any secretarial or stenographic job available. My alma mater made sure of that. I still remember how tough my business teacher Ms. Shumate was. By the time we finished her course, the best of us could take dictation at 100 words per minute, and type 80 to 90 words per minute. We understood the fundamentals of secretarial work, and the importance of good grooming. Ms. Shumate made sure we would not be caught off-guard during an interview. Not satisfied that we could type and take shorthand, once a week we would have to dress up in proper business attire. Ms. Shumate would call on us one by one to walk up to the front of the classroom for an inspection that included lifting our arms to make sure we had shaved our underarms. But when I went looking for that first job — armed with a high school diploma and secretarial certificate — interviewers could not get beyond my color. On several occasions, interviewers looked embarrassed when they had to compliment me on my skills and then tell me that I was wasting my time — without ever coming right out and saying their company wasn't about to hire a black secretary. I ended up working in the mail room of a local gas company. Instead of typing and filing, I pushed a cart from station to station right alongside a group of white women who had no secretarial skills. I spent my free time coaching those who had failed their secretarial skills test. I neither complained nor moped about, but energetically pushed that mail cart until I landed another job in a steno- 16/November 1995/Illinois Issues graphic pool at the local telephone company. It still amazes me that I did not protest this blatant unfairness. Instead, I took it as a fact of life, despite the endless rhetoric about how opportunities had opened up for blacks. Those opportunities, for the most part, merely meant that government, and those entities doing business with government, were compelled to let some blacks inside. The goal of state Sen. Walter Dudycz' bill is to dismantle this system by prohibiting the state or any of its political subdivisions from using "race, color, ethnicity, gender or national origin" as a criterion for either discriminating against or granting preferential treatment to any individual or group. To pass such a bill, one must believe that all things have been made equal between the races. But as President Bill Clinton concluded when he called for a review of affirmative action programs, we are not yet at the point where the playing field has been leveled. In Illinois, two-thirds of state agencies are more than 80 percent white, with minorities bunched up in the social services areas, including the Department of Public Aid and the Department of Children and Family Services, according to reports filed by the agencies. In 1993, among state workers, white men held most of the state jobs that paid more than $30, 000 a year. It is no wonder that it took nearly 30 years for me to reap one single solitary benefit from affirmative action. Five years ago, I was hired as the Chicago Sun-Times' first- minority and scholarship intern. I had returned to college two years previously after giving up the notion that I would ever break out of the secretarial gridlock, despite excellent credentials. While white secretaries had no difficulty getting promoted to better jobs, talented and hardworking black secretaries were regularly passed over. When my supervisor had to come and tell me that I was yet again being held at the gate — this after a decade of service — with no explanation other than a "you know why," and a pitiful expression, I gave notice. So there I was: middle-aged, family to feed, mortgage to pay, and embarking on a new career. I didn't think twice about accepting the Sun-Times' set-aside scholarship. To my way of thinking, I had earned the opportunity to succeed or fail. Besides, the program served to increase the pool of African- American journalists, something that clearly would benefit the industry in the long run. Nearly three decades after the Kemer Commission report called for an aggressive hiring strategy of African Americans by the nation's media, newsrooms across America are still nearly lily white. In the end, an opportunity can only carry you so far. Individuals, both black and white, must prove that someone's faith in their abilities hasn't been misplaced Blacks were needed in newsrooms to add their voices. Without them, the coverage of issues affecting us all would continue to be distorted and told from a narrow perspective. After all, reporters don't just bring their writing talents to the newsroom, they bring their life experiences. When I came to the Sun-Times, I was not only black, but I was a woman and a mother. And I had grown up in an allblack environment in one of the most impoverished areas in the city. Those experiences, while not unique, set me apart from many of my peers. So when certain stories break — such as the tragedy that occurred last year when 5-year-old Eric Morse was thrown from a window of the very building I once lived in — I am able to bring a perspective to the coverage that many other reporters cannot. There are other reasons for diversity in the workplace as well. The population in Chicago, as with many other urban areas, has gone from predominantly white to predominantly minority — with blacks and Hispanics gaining a bigger share of the political pie. It is only reasonable to expect that the makeup of the news media will begin to reflect such a shift. Even with such an obvious disparity, one of the arguments against affirmative action is put forth by black conservatives, who argue that there is a stigma attached to beneficiaries, like a scarlet letter across one's chest. White folks, they fret, will always wonder, "Was she hired because of her unique skills and potential, or was it because she is black?" Of course, both answers contain some element of truth. But those truths are only starting points. In the end, an opportunity can only carry you so far. Individuals, both black and white, must prove that someone's faith in their abilities hasn't been misplaced. Those committed to diversity know this. That is why many companies bolster their affirmative action hiring with auxiliary programs that include mentoring and additional educational opportunities. Affirmative action cannot undo the nation's past racism, but it still serves as an equalizer to balance real discrimination. It is by no means a perfect system, but because of the opportunities such programs provided, people like me found a way around someone else's biases. November 1995/Illinois Issues/17

|