|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

By JENNIFER HALPERIN A return to orthodoxy

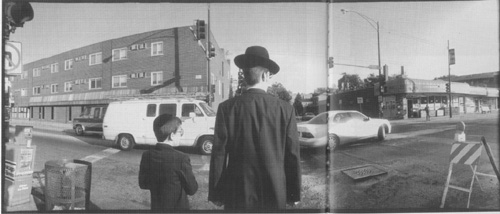

Photograph © Bill Stamets The growth of the Orthodox Jewish community in Chicago's West Rogers Park reflects yearning for family and tradition 26/November 1995/Illinois Issues When Julie and Mark Steinberg's son Yudi was born nearly two years ago, it was a joyful occasion mixed with some anxiety for the young couple. In Orthodox Judaism, the birth of a son calls for his parents to host a shalom zachar — a celebration welcoming the child into the world — on the first Friday night after his birth. Because Yudi was born several weeks before he was expected — and on a Friday — Mark had only hours to prepare the feast. He left the hospital, Julie recalls, nervous that he didn't have nearly enough time to buy groceries, cook and prepare their home for guests. As it turns out, he needn't have worried. "By the time he got home from the hospital," says Julie, "there were boxes and boxes of food piled outside both our front door and back door. I'm talking full meals, wine, liquor, desserts ... we had food piled in our freezer for literally six months. It seems like the entire Orthodox community, from friends to people we did not even know, brought something." It was one of several times Julie felt her neighborhood in West Rogers Park, on Chicago's far North Side, more closely resembles a tight-knit, supportive village — a shtetl, as she puts it — than a section of one of the most booming metropolitan areas on the planet. The community has become a hub for Orthodox Jews throughout the Midwest during the past 20 years, says Philip Lefkowitz, an Orthodox rabbi who lives in West Rogers Park and sits on Chicago's Commission on Human Relations. Although the population has not been formally tracked, a 1990 study by the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Chicago found that more than 10, 000 Jews in the Rogers Park and North Park neighborhoods observed several Orthodox customs. Young people who grew up Orthodox — or who turned to this most observant of Jewish denominations later in life — are congregating here with their families, says Rabbi Israel Fishweicher, president of the Chicago Rabbinical Council. They work all over the Chicagoland area, as everything from surgeons to computer programmers, but at home they carry on the 3, 000-year-old Orthodox way of life. Disintegration of the modem family and disconnection from familial roots have spawned a wave of Jewish youth embracing this lifestyle, he says. "Orthodoxy pushes a strong family sense, and that's what brings them back in. The closeness is what they want for themselves." For Julie Steinberg, who was raised in a nonreligious Jewish home, this was a major motivation. "This way of life is very, very family oriented," she says. "So many of the cus- November 1995/ Illinois Issues/27

Photograph © Bill Stamets toms and traditions are based on gathering family and friends together." The long history, too, of Orthodox Judaism appeals to people. "Young people want to know why their grandparents and ancestors lived this way, and why more recent generations have turned away from it," Fishweicher says. "It has very deep roots." Indeed, to an outside observer, there are scenes in this community that hearken back to another time and place: Groups of full-bearded men in long dark coats and wide-brimmed black hats walk to synagogue on Saturday mornings, their heavy garb a constant, even when temperatures rise into the 90s. Young Orthodox women in wigs, long skirts and knee socks visit kosher merchants along Devon Avenue to stock up for their Sabbath meals. In a schoolyard, a group of young boys wearing the small round head coverings known as yarmulkes play catch, their shouts punctuated with Yiddish exclamations. White fringe, or tzitzis, peeks from beneath their shirts; they wear their hair in payos, which hang in curls along their face. But to those inside the community, it is the common observance of the Jewish holy book Torah that lends West Rogers Park a village-like camaraderie. Those who follow the Torah observe the Sabbath strictly: From sundown Friday to sundown Saturday they do not work, do not carry money, do not use electricity and do not travel, except by foot. "There's a warm feeling," says Lefkowitz, who has lived in West Rogers Park for almost a dozen years. "I walk down the street on a Friday night, and I can see Sabbath candles in window after window after window. It's a good time for friendships, a time for family to be together. In my home, there's not a tremendous gap between the generations because we do a lot of things together every single weekend for the Sabbath. My teenage son and I stand next to each other at synagogue. We have dinner together. I always know what he's doing." Besides the family closeness, people are drawn to this traditional way of life in reaction to the increasingly high-tech world around them, says Rabbi Yosef Kazen, who operates a computer bulletin board on Judaism and studies Orthodox sects across the nation. "There's been movement toward this lifestyle for 30 years," he says. "People are looking for meaning in life. This way of life offers a tranquil environment; it offers an island of peace on the weekend that's family oriented. We're experiencing and reliving what's been going on for 3, 000 years." That's not to say there aren't strains within the Orthodox community. The financial burden of private day schools _ which emphasize a Jewish education — is tremendous. Orthodox families believe public schooling, even supplemented with after-school training at synagogue, is insufficient to educate a Jewish child culturally and religiously, Lefkowitz says. But Orthodox families have an average of six kids, Kazen says. And at $3, 000 to $4, 000 a year for each child, the cost of day schools can be nearly impossible for parents. For this reason, the community supports government vouchers that can be put toward private education. Another "sore spot" in the community, says Lefkowitz, is that there are no lay leaders within West Rogers Park _ '''no plan for growth, no plan to keep up housing." He worries that as buildings become older, landlords will sell rather than refurbish. If parts of the neighborhood become run-down, residents could flee — as they have from other parts of the city — and break up this tightly knit community. He also worries there are no plans to develop affordable housing for large families. "When families have five or six kids," Lefkowitz says, "they can't live in one- or two-bedroom apartments. We've spent literally millions of dollars between synagogues, schools, the Jewish Community Center; now I'd 28/November 1995 / Illinois Issues

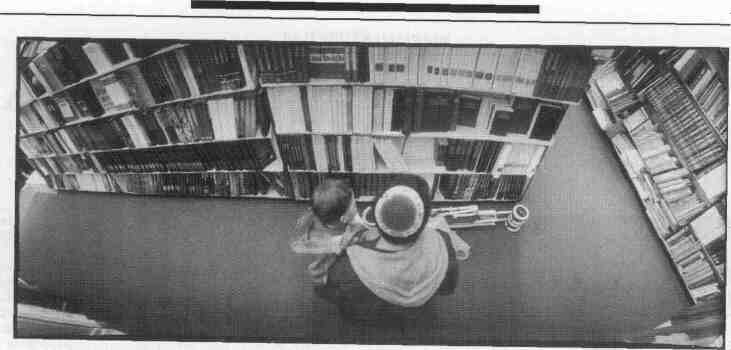

This young man is considering the purchase of material, for a Sutkah - a temporary house that is built to be used during the holldiday of Sukkot. Although the po;ulationhas not been formally tracked, a 1990 study by the Jewish Federation of Chicago found that more than 10,000 Jews in the Rogers Park and North Park neighborhoos of the city observed several Orthodox customs. like to see us move toward planning overall for our development as a community." And, for all the growth and vitality of this community, its perspective is not well represented politically. In many ways, Orthodox Jews are conservative people. As a group, they don't have the stereotypical "liberal" mindset many expect from Jews. They are against abortion and gay rights; they favor school prayer and vouchers for education. They don't use birth control. Yet they haven't tapped their political potential. "Their numbers are large enough to start affecting public policy," says Democratic state Rep. Lou Lang, who represents West Rogers Park. "I know their views on many social issues, and I know ... I have some sizable differences of opinion with them on certain social issues. But, like a lot of growing minority groups, they haven't put their political beliefs all together for the larger public." Due to their relatively small numbers compared to the Reformed and Conservative denominations of Judaism, says Lefkowitz, the Orthodox have been left out of the larger political dialogue. Further, adds Fishweicher, there is a schism between some older Orthodox Jews who want to leave politics to others and younger members who want to use the community's clout to effect change. "I think the next generation will be more active," he says. "They understand the importance of getting out the vote, and making your political voice heard." And today's political and cultural climate may provide a sympathetic forum for them. Emphasis on family and community would be a welcome message to many young people who grew up in more fragmented worlds. "Society is moving in a more conservative direction," says Lefkowitz. "The standards of human relationships are gone _ that's why people are moving toward the fundamentals of religion, whether Islam, Christianity or Judaism. When I look at the problems in the world, Judaism is a very good answer." Julie Steinberg agrees. "In a time when the nuclear family has suffered a tremendous meltdown — which has caused many ills of our society — this way of life keeps the family together. I wanted my children raised in a way that holds these things sacred." November 1995/ Illinois Issues/29

|