The State of the State

Child death review teams try to keep kids alive

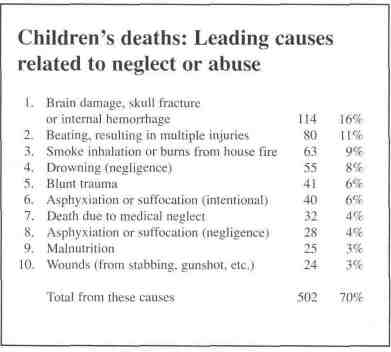

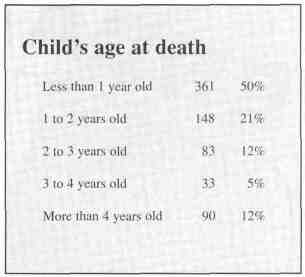

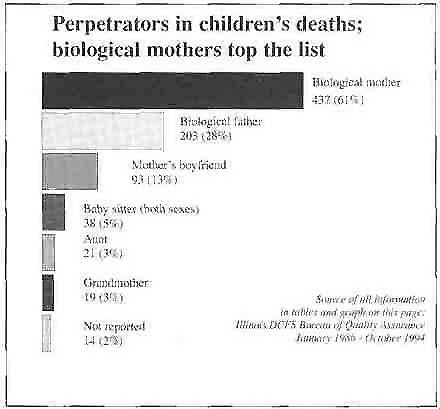

'Nobody can prevent idiosyncratic behavior that leads to kids' deaths, but often there's a long buildup' By JENNIFER HALPERIN Illinois officials bristle when this state is chastised for lagging on policy issues. After all, politicians don't like to be considered followers rather than leaders. But, unfortunately, we have another example to prove the point. After more than 30 other states set up regional teams to investigate the deaths of children through abuse and neglect, Illinois has launched its own program. Few would say the state acted too quickly. Between 1986 and 1994, 715 child deaths in this state were attributed to abuse and neglect, according to the Department of Children and Family Services. In one-third of the cases, there were prior reports of maltreatment. In 95 percent, the victims' families were deemed involved in the children's deaths. "We absolutely were falling behind," says state Rep. Jay Hoffman, a Democrat from Collinsville who has tried for years to get fellow lawmakers' support for these teams. "Illinois had nothing in place to coordinate different professionals' services to look into these deaths." The idea behind these DCFS-coordinated teams is simple — almost commonsensical. Bring together professionals in law enforcement, medicine, social services and education, and ask them to look into any child's death whenever it was caused by abuse, neglect or other factors they believe could have been prevented. Ask them to take clues from each death and recommend ways to keep other children from suffering the same fate. Last year, the idea was signed into law. This year, nine teams are up and running — two in Cook County, seven elsewhere in the state. And already they are reporting a cooperative attitude between team members, the DCFS and other agencies. "Nobody can prevent idiosyncratic behavior that leads to kids' deaths, but often there's a long buildup," says Neil Hochstadt, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago medical school. "Often they could have been prevented by one person's stepping in to save a life." Hochstadt chaired a statewide task force that recommended setting up the new regional teams. He says the Cook County teams already have seen results from their cooperative studies of children's deaths. There was a case in one Chicago suburb, he says, in which police didn't know how to proceed before involving the child death review team. It seems the autopsy showed the victim had been battered, but both parents denied it. A DCFS worker on the team looked into the case and found that the mother's family had taken photos of the child that showed bruises before his death. Hochstadt says the caseworker and police officer on the team got advice from a team member who works with the state's attorney's office, and eventually they gathered enough information to charge the father in the child's death. In another case, two parents went to pick up their daughter from their baby sitter's home and found her unresponsive. They rushed her to a nearby hospital, where she died soon after. An emergency room physician told police the child had been shaken to the point of being braindamaged, but that the shaking could have occurred anytime within a 24-hour period. When police brought the case to the death review team, though, a forensic pathologist studied the case and determined the shaking had to have occurred within five minutes of the parents' time of arrival at the baby sitter's home. Ultimately, the baby sitter was charged in the child's death. "This was a case where the police may have been steered off track and given the wrong information by a doctor in an emergency room," Hochstadt says. "But these teams get people talking to each other. They open lines of communication between agencies that otherwise might be operating in a vacuum, each going on fragmented information." Regional task forces have flexibility to 8/December 1995/Illinois Issues

tackle whatever issues they deem appropriate, along with abuse and neglect prevention, Hoffman says. If some teams want to focus on bicycle safety, for exam ple, or preventing Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, they're free to do so. Anything that could help prevent kids' deaths is considered fair game. The first child death review team in the country was started in Los Angeles County in 1978 by Dr. Michael Durfee. "Everybody does their piece of the job better," says Durfee, who coordinates child abuse prevention programs for the Los Angeles County Department of Health. "Better autopsies, better child protective services. ... Agencies are connected with each other in ways they never were before." For instance, he says, police investigating a baby's death might not ask to see the baby with its clothes off, whereas a health professional would. "The cops we worked with used to have this Clint Eastwood mentality," Durfee says. "Over the years they've learned how to work with others and look for things that also have to do with the child's family situation and other factors." Hoffman hopes all of the Illinois teams yield similar positive feedback. In any case, he says, it was time to try a new approach to preventing these kids' deaths. "I don't think we should have the attitude that bureaucrats have all the answers," Hoffman says. "We should use experts to come up with solutions. If mistakes have been made, let's correct them. Don't hide problems under the rug. Make sure that out of tragedy comes something positive."

December 1995/Illinois Issues/9

|

|||||||||||||||