An essay by HAROLD HENDERSON

Illustrations by Olin Harris

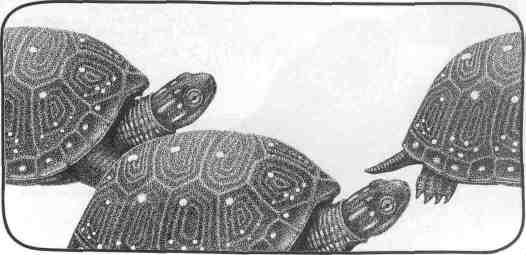

Spotted Turtle, Clemmys guttata Danger zone Weakening the Endangered Species Act may be the only way to save threatened species 10 / December 1995 / Illinois Issues The most alarming thing about the Endangered Species Act, now up for reauthorization in Congress, is the debate over it. Or should we say the shouting match? Pew involved seem to have the common sense to care about both economics and environment when they conflict. And few politicians seem willing to do what politicians do best — force the two sides to sit down and deal. Earlier this year, environmental writer Gregg Easterbrook asked a good journalistic question about the alleged extinction crisis in his book A Moment on the Earth: Where are the bodies? If we are exterminating 50,000 species a year worldwide, as the eminent Harvard entomologist E.O. Wilson has suggested, then (very roughly) some 66,000 species should have been hounded out of existence in the United States alone since 1973, when the Endangered Species Act was passed in its current form. Easterbrook's 66,000 figure is too high because it assumes wrongly that species are evenly distributed over the globe. But even so, where are the bodies? "Of the first group of species listed in 1973 under the Endangered Species Act," Easterbrook writes, "today 44 are stable or improving, 20 are in decline, and only seven, including the ivory-billed woodpecker and dusky seaside sparrow, are gone. This adds up to seven species lost over 20 years from the very group considered most sharply imperiled. ... There is a rather amazing gap between a projected 66,000 and a confirmed seven. And the United States is the most carefully studied biosphere in the world, making U.S. extinctions likely to be detected." Peter Raven — director of the Missouri Botanical Garden, MacArthur fellow and an authority on biodiversity — reviewed Easterbrook's book in the Natural Resources Defense Council's Amicus Journal. Referring specifically to this chapter, he sneered at Easterbrook's "glib style," and "superficial reading of secondary sources," and lamented that he is "clearly confused regarding the facts." The one thing Raven did not do was address Easterbrook's question. This non-exchange is tame stuff compared to the spotted- owl wars in the West. But it's a good example of why the 1973 Endangered Species Act — and endangered species themselves — are in as much danger from their self-proclaimed friends as from Republican yahoos. When ardent environmentalists choose to meet attempts at informed criticism with abuse, they are asking for trouble. The other side is no better. In its critiques of the Endangered Species Act, the right-wing Competitive Enterprise Institute is solicitous of allegedly wronged landowners. But its proposals — such as "allow states and Indian tribes to opt out of the federal program entirely" and "leave the conservation of foreign species to foreign governments" — are transparently obvious attempts to accomplish nothing. They display a profound and willful ignorance of the benefits — aesthetic, economic, medical and ecological — that other species offer human beings. If serious negotiations on this issue ever do take place, perhaps they should start from a surprising premise: The Endangered Species Act is too strong for its own good. A species listed as threatened or endangered cannot be disturbed without the OK of the U.S. Department of the Interior. "Congress viewed the value of endangered species as

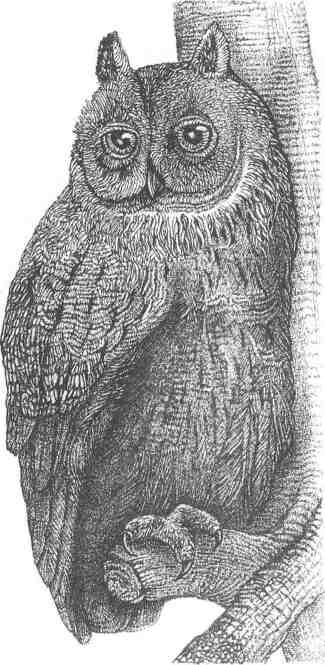

Long-eared Owl, Asio otus Endangered in Illinois December 1995/Illmois Issues/11 'incalculable,'" the Supreme Court explained in the famous 1978 case that pitted the tiny snail darter fish against the TVA's Tellico Dam. The law provides no way to balance the survival of such species (or subspecies, or populations) against other competing values. Its "plain intent" was "to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost." We Americans are a romantic people living in a romantic era. We like the idea of pursuing a worthy goal "whatever the cost." But such an approach is philosophically untenable, economically unsound and politically disastrous. Philosophically untenable Preserving all kinds of plants and animals is a good thing. Elephants and soil bacteria, orchids and clams are beautiful and inspiring. Each species is a repository of valuable information and potentially unique resources for medicine and crop improvement. As a group, they process waste, exhale oxygen and provide other "ecological services." These facts are not in dispute. They're well documented in E.O. Wilson's books and in the concluding chapter of Critical Condition: Human Health and the Environment, published by Physicians for Social Responsibility. They are the indispensable foundation of any intelligent discussion of the Endangered Species Act. But no good is absolute. In their highly readable and scrupulously fair book, Noah's Choice: The Future of Endangered Species, Charles Mann and Mark Plummer tell how in 1990 the Endangered Species Act prevented the state of Oklahoma and the Choctaw Nation from completing a 13-mile gap in State Highway 82 through the Sans Bois Mountains, a route which would have made it much easier for area Native Americans to get to the Choctaw Nation Indian Hospital near Talihina, Okla. But, in the words of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the highway was "likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the American burying beetle," Nicrophorus americanus. So it was not built. Mann and Plummer are not making a joke out of this.

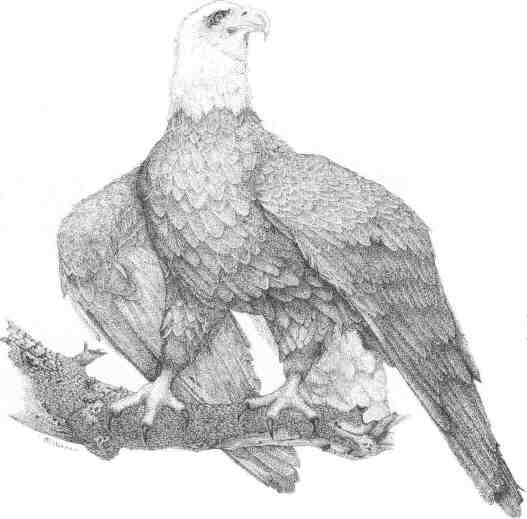

Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus Endangered in Illinois and federally Neither am I. To kill off the last one of anything is a terrible, heavy decision. But neither is it an easy decision to (in effect) tell an Indian woman in labor that she must either travel an extra 50 miles to reach the hospital or find a four-wheel-drive vehicle that can follow the dirt roads through the mountains. True, exterminating the beetle is irreversible, but so is a human death that could have been prevented by timely arrival at the hospital. The point is that these are competing goods; such situations do not pit evil "developers" against an innocent creature of God. The decision is agonizing; it's not automatic. As currently written, the Endangered Species Act pretends that it's automatic. Does the American burying beetle have some kind of inalienable right to continued existence that trumps all other concerns? Not in the natural scheme of things. Species rarely last longer than 10 million years before vanishing; roughly 99.9 percent of the species that ever existed are extinct. 12/December 1995/Illinois Issues Economically unsound We can't afford to confer full protection on every endangered species — in the same sense that you can't read every book in the U of I library. Even with the best will in the world, there just isn't enough time, or money, to go around. Understanding this is not exactly brain surgery: If you spend extra for your children's education, you spend less on their insurance. It's prudent to buy insurance, and preserving biodiversity can be viewed as an important kind of insurance; it's not prudent to spend all your money on insurance. Even within the universe of endangered species, the same principle applies. Money spent to save the Florida panther, a subspecies of panther, cannot also be spent on whole species in danger of extinction, such as the black-footed ferret or the whooping crane. As Steve Packard of The Nature Conservancy told the Chicago Reader earlier this year, "You can say, 'I'm Noah and I'm going to save everything — even every blade of grass. After all, what if there's some unique and valuable mold on that leaf?' If that's your attitude, you'll be a poor steward of the land because a lot of things will go extinct while you're working on something less important." On the subject of cost, environmentalists can seem schizophrenic. Defenders of the act as written sometimes assert that the costs of protecting endangered species are negligible. A recent study by Massachusetts Institute of Technology political scientist Stephen Meyer found no measurable correlation between the number of federally listed species in a state and its gross state product or number of construction jobs. That suggests that the economy is more resilient than property-rights activists care to acknowledge; it does not imply that we can protect continually increasing numbers of listed species at no cost. There is an exact ecological parallel: Believers in Barry Commoner's ecological "law" that "everything is connected to everything else" do not like to acknowledge that we have gotten along fine without the passenger pigeon. But ecosystems' remarkable resilience does not imply that we can let any number of species go extinct with no consequences. On the other hand, defenders of the act would also like to go well beyond it. Writing in the journal Science in August 1991, Paul Ehrlich and E.O. Wilson urged that we take the "first step" toward protecting biodiversity: "Cease 'developing' any more relatively undisturbed land." That's hardly a prescription with zero economic impact. And in their 1994 book, Saving Nature's Legacy, conservation biologists Reed Noss and Alien Cooperrider are only slightly less grandiose: "Calculations of the area necessary [to preserve in order] to represent all species and ecosystem types in a region can run as high as 99 percent [of an area], but are usually in the range of 25 to 75 percent... an order of magnitude beyond what is currently protected in most regions. We harbor no illusions about our vision being easy to accomplish. A smaller and better-educated human population is ultimately required." Good public policy depends on good science. But proposals like these show why decisions about endangered species cannot simply be turned over to the biologists (or economists!), no matter how high-minded they may be. Experts get to be experts because they only care about one thing. Politically disastrous Even if species had an absolute right to survival, and even if there were an infinite supply of time and money to guarantee it, a law that makes it an absolute priority is likely to engender an absolutistic backlash. The argument has been made that the Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortions turned out to be a long-run political disaster for advocates of reproductive choice.

River Otter, Lutra canadensis Endangered in Illinois December 19951 Illinois Issues/13

Yellow-headed Blackbird, Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus Endangered in Illinois Instead of gaining political support state by state (as was supposedly happening in the early 1970s), they were handed a nationwide victory, demobilizing them and ultimately galvanizing a dedicated opposition — an opposition that would have had much more difficulty mobilizing without a Supreme Court decision to demonize. The Endangered Species Act may also suffer from Premature Success Syndrome. By making species protection an absolute priority, it has provoked a desperate and often irrational reaction. The act creates a core constituency with powerful reasons to oppose it. Most listed endangered species have most of their habitat on nonfederal lands. If your land is found to harbor one, then you immediately lose a lot of control over what changes you can make on it — and you get nothing in return. Whether the changes you wanted to make involved making money, personal safety or personal preference is irrelevant, for the same reason that the First Amendment protects moronic insults as well as important policy-wonk articles. Preserving biodiversity is a valid public goal that may often dictate limits on property use. But why should the individual landowner bear the full cost on society's behalf? The answer had better not be, "Because we could never get a tax increase passed to buy the land needed to protect endangered species." If Americans are unwilling to pay for the environmental preservation the vast majority tell pollsters they want more of, then they don't really want it. Getting it on the cheap by laying the cost on randomly selected landowners is just an abuse of power. Besides being unjust, it's inefficient. The law, as written, encourages landowners to lie about or eliminate endangered-species habitat, or even the creatures themselves. And by making preservation seem free, it encourages the government to try to protect everything. As Thomas Lambert of the Center for the Study of American Business at Washington University in St. Louis writes, "Requiring the government to compensate landowners for their lost property value would force regulators to consider the technical practicability of recovering a species, the species' biological and aesthetic significance and other costs and benefits of saving the species. These deliberations would result in much more sensible decisions about which species to protect and in which locations." And by the way, the tools for more sensible decision-making are at hand. If our goal is to save as many species as reasonably possible, a July 21 article in Science by Stuart Pimm and colleagues shows that the most vulnerable species are those with limited geographic ranges — called "endemic species" — and that they tend to occur in "hot spots" rather than uniformly across the globe. In Illinois, for instance, freshwater clams in rivers tend to be endemic, and the state Natural History Survey reports that more than half of them are either extirpated from the state or in danger. Also in Illinois, we can all draw on the authoritative resource — little noticed by journalists — of the seven-volume The Changing Illinois Environment: Critical Trends, published last year and available from the Department of Natural Resources. New and improved So, what to do? An improved Endangered Species Act would be conservative, by acknowledging competing values and including a mechanism to weigh them. It would provide compensation for landowners who suffer significant loss through no fault of their own. Liberal populists who idolize grass-roots resistance to incinerator siting and who demonize grass-roots resistance to endangered-species designations do not understand their own principles. An improved act would also be environmentalist, by placing a high priority on protecting species and their habitats, and by acknowledging our need to learn much more about both. It would include increased funding for the interior department's research arm, the National Biological Service, especially money to train more taxonomists and support their work. Conservatives who slash research budgets and then argue against protecting species "because we know so little about them" are like children who murder their parents and then beg the court for mercy because they're orphans. Neither group of advocates has distinguished itself in this debate so far. Conservatives' disinterest in the natural world is often painfully apparent. Most environmentalists' disdain for legitimate private property rights is equally plain. In this situation, courageous politicians will not mouth the party line on either side. They will use their power to bring about dialogue and compromise. Harold Henderson is a staff writer for the Chicago Reader.

14/December 1995/ Illinois Issues

The Prairie State has already lost the

buffalo, the black bear, the elk and the

timber wolf. Now, according to the

Illinois Endangered Species Protection

Board, 511 species in the state are facing possible extinction. They've been

listed by the board as either "endangered" or "threatened."

A century ago, animals were driven

from their Midwest range by hunters.

Today, plants and animals are more

likely to be exterminated when their

habitats are destroyed.

In fact, about 40 percent of the

state's endangered species depend on

our dwindling wetlands for survival.

The highest concentrations of such

species have been recorded by the

board in areas with remaining wetlands: the northeast corner and the

southern tip of the state, with one patch

in the state's west-central region. Lake,

McHenry, Cook, DuPage and Will

counties are among 12 in Illinois with

50 or more known endangered species.

Lake holds the state's record at 300.

Unfortunately, Illinois has lost al-

most 90 percent of its wetlands due, in

part, to modem farming practices. Now

Congress is debating proposals that

could reduce programs designed to protect wetlands, and encourage farmers to

put more acres into production.

A plant or animal is listed as "endangered" in Illinois, officials say, if it

could soon disappear as a breeding

species in the wild. Appearance on the

"threatened" list is an indication of

trouble, though less immediate.

• The board lists 21 endangered fish

in Illinois, including the lake sturgeon

and the sturgeon chub.

• Among the nine endangered reptiles and amphibians are the spotted turtle and the Illinois mud turtle. In addition, the alligator snapping turtle is

threatened, as is the Illinois chorus frog.

Among the threatened species we

may not want to see firsthand are the

timber rattlesnake and the Great Plains

rat snake.

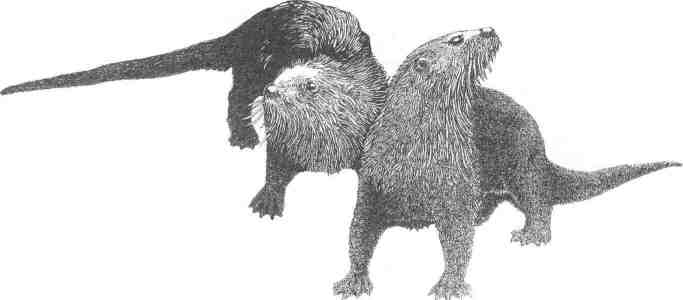

• There are six endangered mammals, including the favorite, the river

otter, and the not-so-favorite bats (the

gray bat, the Indiana bat and the

Rafinesque's big-eared bat).

• Of the 33 endangered birds, the

bald eagle, the osprey, the peregrine falcon and the sandhill crane may be the

most commonly known. But there are a

host of hawks, owls, herons and even

sparrows on the list.

• By far, plants make up the longest

list, with 306 endangered species —

including orchids and lilies — and

another 57 threatened species.

Peggy Boyer Long

December 1995/Illinois Issues/15

|

|||||||||||||||