By KENT D. REDFIELD

Cash clout

Political money in Illinois legislative elections: New book tracks the flow of campaign contributionsFor a while during the spring of 1993, it appeared the General Assembly would pass an abortion bill for the first time in four years. The right-to-life supporters went head-to-head with the pro-choice supporters over a parental notification bill. The right-to- life forces won in the House and again in the Senate when the bill came up for votes on final passage. It seemed certain that a bill would reach the governor's desk requiring women under the age of 18 to notify a parent before getting an abortion. Instead, the bill was defeated in the House when it came back for a vote on changes made in the Senate. That defeat came after last-minute objections by one of the most powerful interest groups in Illinois — the Illinois State Medical Society — which opposed penalties for doctors who knowingly violated the law. After the Medical Society signaled its opposition, 13 legislators who had supported the bill in the House changed their votes to no or present.

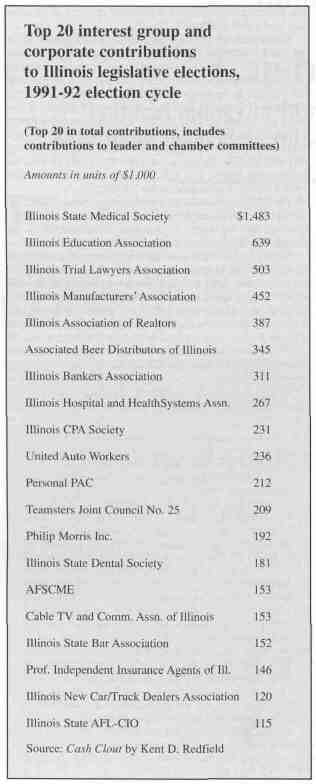

Why was the Medical Society successful in defeating the bill? The sources of interest group influence are many: large memberships, strong grass-roots organizations, expert knowledge, persuasive representatives and powerful emotional appeals. But the most effective currency of influence in the legislature is cash. Legislative elections in Illinois are expensive and are becoming more expensive with each election cycle. With few exceptions, influential interest groups in Illinois politics are those that contribute large sums of money to the campaign committees of legislative leaders, incumbent legislators and candidates for legislative office. In raising and spending money on legislative campaigns, the Medical Society stands head and shoulders above other interest groups. During the 1992 election cycle (calendar years 1991 and 1992), the Society contributed $1.48 million to the political committees of candidates for the legislature, to those of the legislative leaders and to the chamber political committees. The next largest amount contributed by a single interest group in that election cycle was $639,000, contributed by the Illinois Education Association's political action committee, IPACE. While the IEA is also able to influence legislative elections by directing local volunteers and local education association money to targeted races, the Medical Society's advantage is still substantial. Do those who contribute the most money always win in the legislature? If that were true, then legislation raising the state tax on cigarettes would have remained buried in committee in the 1993 spring session, just as it had in previous sessions. Most of the groups supporting a cigarette tax increase are not- for-profit or public-interest groups, such as the Illinois Cancer Society, that have little or no money to contribute to political campaigns. In contrast, the tobacco interests have a long history of contributing large amounts of money to legislative leaders and members and, until 1985, an equally long history of successfully opposing attempts to increase the tax on cigarettes. A review of the campaign reports of legislative candidates and leaders for the last six months of 1992 shows that two corporations (Philip Morris Companies Inc. and R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.) and one group representing tobacco interests (the Tobacco Institute) contributed more than $240,000 to legislative campaigns during the period. But that money did not prevent the governor and the legislature from incorporating a cigarette tax increase and a new tax on other tobacco products as key elements in the budget agreement passed in July 1993. The major players Who is and is not on the list of top interest group and corporate contributors says a lot about Illinois politics. The list of interest group contributors in the 1990 and 1992 legislative elections is dominated by healthcare providers, public employee and trade labor unions, lawyer associations, and business and financial associations. Missing are environmental and consumer groups and social service organizations repre- 24/ December 1995/ Illinois Issues senting children, the poor and the physically or mentally disabled. Groups representing single issues or ideological positions are also absent, with the exception of Personal PAC, a group advocating choice on abortion. It's a paradox that large categories of people with common interests, such as electricity consumers or healthcare patients, do not organize and raise money for campaign contributions precisely because they are so large. The communication and organizational costs are too great, and the incentives for any individual to act are too small. Raising large sums of money for campaign contributions is almost always the result of the individual actions of corporations, the cooperative actions of a relatively small number of private corporations, or the collective actions of members of professional associations or labor unions. Contributions, access, influence "While the current system of financing elections does not allow you to buy a congressman, it does allow you to lease one." This often repeated gag line, while a commonly held belief, is an oversimplification of the relationship between campaign contributions and influence in the Illinois General Assembly. A straight quid pro quo between an interest group and a legislator on a vote is both unusual and illegal. What interest groups and corporations seek through campaign contributions, first of all, is access — a foot in the door. Lobbying is communication. But even before lobbyists can present their positions and rationale, they must gain access to the decision-makers. After all, if legislators won't return phone calls or meet face to face to discuss legislation, lobbyists will have little influence on their voting behavior no matter how persuasive the arguments and coherent the analyses. Campaign contributions ensure that phone calls are returned and meetings are held. They are not, however, the only means for gaining access; a strong grass-roots organization, connections with a legislative member and a reputation for good policy research or good political analysis are all ways to gain access to legislators. But most interest groups will form PACs and make campaign contributions if they have the resources. Contributions provide direct links to legislators and signal that the interest group is a serious player in the legislative game. Ultimately, groups that arc organized are better able to raise money, and money helps groups communicate with legislators. If interests with money want to pass a bill and those who might be affected are unorganized and silent, the outcome almost always favors the organized. The Illinois New Car/Truck Dealers Association ranked 18th on the list of the largest interest group contributors to legislative elections in 1990 and 19th in 1992. Nowhere on the list do you find the buyers or potential buyers of cars. It is not surprising that the law that makes it illegal to sell cars in Illinois on Sunday was passed at the request of the new car/truck dealers and that they have successfully resisted attempts by individual legislators to repeal the ban. In addition to access, campaign contributions may provide leverage with a legislator for an interest group because they can be increased, decreased, withdrawn or given to an opponent in the next election. The importance of campaign contributions was reflected in the number of newspaper stories in November 1993 concerning the upcoming vote in Congress on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Many national labor unions came out strongly in opposition to NAFTA and openly threatened members of Congress with the withdrawal of support if they voted for the treaty. Many of those members struggled openly with their vote in the face of that threat. While the role of campaign contributions in a legislator's voting decisions is rarely on public display the way it was prior to the vote on NAFTA, the potential impact of a roll-call vote on campaign contributions is always a consideration for legislators. The opposite outcome of votes on the parental notification bill and the cigarette tax increase in the 1993 legislative session illustrate the influence of campaign contributions in the General Assembly — and the limits of that influence. When parental notification came back to the House for concurrence in the changes made by the Senate, the Medical Society, which had previously taken no position on the bill, signaled that it had concerns with the penalty provisions that could be applied to doctors. When the sponsors indicated they were not interested in entering into new negotiations on the bill, the Society took a position in opposition. When the bill came up for a vote on concurrence, it received only 53 votes, down 11 from the first vote and seven votes short of the 60 needed for passage. While a legislator's position on abortion legislation may cost some votes in an election, it is widely believed by legisla-

December 1995/Illinois Issues/25

tors and political observers that being identified as a person who has flip-flopped on the abortion issue can be even more politically damaging. Deciding to change a vote on an abortion bill may be all the more significant because of this. Of those 13 legislators who changed their votes, 12 received campaign contributions from the Medical Society. Four legislators received contributions totaling between $10,000 and $36,000. The remaining eight received contributions totaling between $1,250 and $3,000. If the only consideration in voting on the bill were campaign contributions, then the seven other House members who voted for the bill on third reading who received campaign contributions of $5,000 or more from the Medical Society would have switched their votes when the bill came back to the House for concurrence. Yet, the Society's campaign contributions and its reputation for aggressive involvement in legislative elections gave it access to a large number of legislators. A legislator's voting decisions usually are the result of a calculation of personal policy preferences, who is supporting and who is opposing the bill, the preferences of constituents, and the intensity of those preferences. The Medical Society's interest in the parental notification bill halted passage of the bill as members considered the Society's opposition and arguments against the bill. While the abortion bill was not as important in the universe of legislative decisions as school funding or a tax increase, its defeat does illustrate the ease with which the Medical Society can exercise political muscle in the General Assembly. No one can know whether the legislators who changed their votes on parental notification did so on the basis of the soundness of the Society's arguments, concern over the resources the group can bring to bear in elections, gratitude for past support, or some consideration unrelated to the Society's opposition to the bill. What is clear is that the Medical Society's campaign contributions give it instant access to legislators and, with it, the opportunity and ability to influence votes. The limits of influence Tobacco interests have long been a strong lobby in the Illinois General Assembly. Taking full advantage of the corporate ability to contribute directly to candidates in this state, they have contributed freely to legislative members and leaders, cultivating key lawmakers as supporters. As a result, tobacco lobbyists have generally been successful at resisting attempts to increase the cigarette tax, even when those initiatives came from the governor. Faced with a series of budget crises in the 1980s, then-Gov. James R. Thompson proposed raising cigarette taxes on several occasions in an effort to finance state budgets. Two of these proposed increases passed, one in 1985 and one in 1989. Gov. Jim Edgar included a cigarette tax as part of his first budget proposal, but was not able to get it enacted. However, during the 1993 spring session, despite the $240,000 tobacco interests contributed to legislative elections in the 1992 cycle, the legislature passed a cigarette tax increase and imposed a tax on other tobacco products for the first time, all to help fund the state budget for the 1994 fiscal year. 26/ December 1995/ Illinois Issues While the tobacco interests' campaign contributions do give them considerable access and influence in the General Assembly, they also are limited in comparison to the most powerful interest groups in Illinois politics. Unlike the IEA or the Medical Society, they don't have a strong grass-roots organization that is active in most legislative districts in the state. Unlike the Illinois Manufacturers'Association, they don't represent the employers of large numbers of Illinois workers. And, unlike the beer distributors, the consumers of their products aren't favorably portrayed in TV commercials every night. The continuing budget crisis in 1993 gave the governor and the legislature few options once a general tax increase was ruled out. Once the cigarette tax increase had the backing of the governor and the four legislative leaders and became part of the budget agreement, no amount of lobbying by the tobacco interests was able to defeat the increase. The unified position of the governor and the leaders provided political cover for the members and left the tobacco interests with a major defeat. The more things change In the end, legislators control their own votes. This limit on the ability of interest groups to influence legislators through campaign contributions is captured in a comment attributed to the late Jesse Unruh, speaker of the California House in the 1960s. Noting the relationship between interest groups and legislators, he said, "If you can't take their money, eat their food, drink their booze, screw their women, and then vote against them, you don't belong here." While sex and booze are less important in the legislature of the '90s, due to changing mores, increased press scrutiny and tougher lobbying reporting laws, the same cannot be said for money. The cost of legislative campaigns in Illinois will continue to escalate because of the intense competition for control of the legislature and the absence of limits on how much can be contributed to or spent by a candidate. And legislators facing re-election will find it more difficult to "take their money and vote against them." Simon, Stratton co-chair Illinois Campaign Finance Task Force U.S. Sen. Paul Simon and former Gov. William Stratton are co-chairing a new task force created to analyze campaign contributions. The Illinois Campaign Finance Project will examine contributions from 1990 to 1994. The group, which will issue a report in 1996, is expected to recommend changes in the state's campaign finance laws. Illinois Issues received a two-year grant from the Joyce Foundation to coordinate the project. The magazine's publisher, Ed Wojcicki, in cooperation with the Institute for Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Springfield, will head the project. Kent D. Redfield, associate director of the Illinois Legislative Studies Center at UIS and author of Cash Clout, will be the principal investigator. The project has three components: • Creating a statewide task force. Additional members of the group will be named in the near future. • Researching contributions and expenditures in the 1994 election cycle and conducting interviews with the individuals who raise and spend campaign money. Project staff is creating a computer database of all contributions and expenditures in 1994 for the six constitutional officers and for each member of the General Assembly. The database will be designed to track groups that made contributions, to analyze the flow of money from legislative leaders to targeted races and to help citizens' groups and media throughout the state gain better access to information about contributions and expenditures in their local areas. Researchers are supplementing the campaign finance data with survey research, case studies and interviews with several dozen key players, including lobbyists, candidates, current and former officials and major contributors. • Educating the public. The research will provide the foundation for a major public education effort in 1996. Project staff will conduct a series of public forums on the findings throughout the state. And the results of the research and the task force report will be distributed widely, including on the World Wide Web. In addition, the project staff will be able to customize reports for local media or organizations. For more information If you're interested in specific contribution or expenditure data about any candidates, you may call project coordinator Carol Frederick at 217-786-6643 or Wojcicki at 217-786-6084. Or you can make your request on e- mail by writing Frederick at cfredric @uis.edu or Wojcicki at wojcicki @uis.edu. December 19951 Illinois Issues/27

|

|||||||||||||||