Books

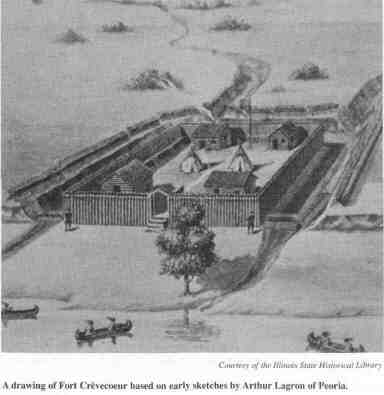

The story of French Peoria contributes another chapter to the stated colonial historyBy TOBY ECKERT French Peoria and the Illinois Country 1673-1846, by Judith A. Franke, Illinois State Museum Society, 1995. $23 (paper). The French occupied a broad swath of Illinois for the better part of a century. But, like the native people they encountered here, the earliest European settlers left a meager legacy. Except for exotic place names — Prairie du Rocher, Creve Coeur, La Salle — and a handful of recreated sites, there is little to mark Illinois' French heritage. Partly that is the result of the nature of French settlements — widely scattered, hardscrabble villages with mostly illiterate and often transient inhabitants. It's also attributable to their fate following the American Revolution and the nation's subsequent westward expansion. Like their Indian allies, the French were, in some cases, forcibly removed from their settlements, their land expropriated by "American" settlers. Others headed west with the remnants of the once great tribes of the prairies. The rest were eventually overwhelmed by successive waves of other, more durable European settlers. Nevertheless, a few historians have waded into the murky waters of Illinois' French colonial history. The latest contribution is from Judith A. Franke, the director of Dickson Mounds Museum. Franke's book, French Peoria and the Illinois Country 1673-1846, grew out of a 1990 museum exhibit that marked the tri- centennial of the French settlement at Peoria. As the name suggests, the book is primarily concerned with French activities in and around their small settlements along the Illinois River around present-day Peoria and East Peoria. But like a detail from a painting, it illuminates the broader story of the French in Illinois by providing some insight into the ways a typical French settlement was ordered — or, as was often the case, disordered — and how the people there lived. The story begins in 1673. A small band of French explorers, led by fur trader Louis Jolliet and Jesuit missionary Jacques Marquette, probed the hinterlands of "New France" in hopes of finding a river route to the Pacific Ocean. After descending the Mississippi River to the Arkansas, the explorers realized the great river would merely take them to the Gulf of Mexico. They returned up the Mississippi and veered east near present- day Grafton, heading up the Illinois River. Citing Marquette's journal, Franke believes the Frenchmen may have spent several days with an Indian tribe near Peoria. Several years later, in 1680, Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and a party of 30 men descended the Illinois River from the Great Lakes and built a small fort, called Crevecoeur, on the east bank of the river, in present-day Tazewell County. Though the fort was soon abandoned by its nervous pickets and fell into disrepair, the era of French dominance of the region had begun. La Salle and his men centered their trading operations upriver, at Starved Rock. But after La Salle's death in 1690, his lieutenant, Henri de Tonti, led a band of French and Indians downriver to establish a settlement on the west bank of the Illinois, at a bulge known as Lake

28/ December 1995/Illinois Issues Books Pimetoui. There they constructed Fort St. Louis and a mission. A settlement of French farmer-traders sprung up and endured for a century. The names of about 60 of the pioneers are known, Franke reports, including Jean-Baptiste Point Du Sable, who later became the first permanent settler in Chicago. For the most part, the French seem to have lived in harmony with the local Illinois tribes, including the Kaskaskia and the Peoria. But there were inevitable cultural conflicts. One Jesuit missionary, Jacques Gravier, caused a stir when he converted the daughter of a Kaskaskia chief. Other tribal elders grumbled that the French were corrupting the youth in other ways, such as encouraging them to marry younger than tradition dictated. More serious conflicts came later, when the French and Indians found themselves on opposite sides of alliances during the American Revolution and the War of 1812.

Franke provides intriguing glimpses into the lives of the French settlers and Indian inhabitants in biographical sketches sprinkled throughout the book. Of particular interest are the property and probate records of Louis Chatellereau, a farmer. The records, the only original personal papers remaining from any of the village's inhabitants, attest to a relatively wealthy individual with a mill, more than a dozen animals and two slaves. But there can be little doubt that life at the isolated outpost was hard, and many of the inhabitants met with violent and untimely deaths. The transfer of the Illinois territory to British control in 1763 following the French and Indian War apparently had little effect upon the village at Peoria. As Franke notes, the British had no effective administrative control of the area, with the Indians under Chief Pontiac in open rebellion and the French showing no inclination to cooperate with their former enemy. Nevertheless, the settlement entered a period of long, slow decline. It was hastened by the American Revolution. At the outbreak of the war, the French inhabitants had sworn fealty to the British. But by 1778, the Americans, led by Col. George Rogers dark took control of the region. A year later, a band of British soldiers and Indians descending the Illinois River for a campaign against St. Louis .apparently attacked Peoria. A new village was founded about a mile downriver in 1778 and the original settlement was abandoned around 1796. But more conflict erupted during the War of 1812, with the French and Indians once again on opposite sides of the front. Following a Potawatomi attack on Fort Dearborn, near Chicago, Ninian Edwards, governor of the Illinois territory, led an attack on a Potawatomi village at the head of Lake Pimetoui. Half the French inhabitants of Peoria fled south. A second wave of American troops that arrived after the attack accused the remaining French settlers of collaborating with the Indians on an ambush. They were arrested and taken to Alton, bringing about the demise of the French village. Six years later, some of the villagers returned to the Peoria area and set up a trading post near the site of Fort Crevecoeur. But the French influence was steadily diminished by an influx of American pioneers. Franke's account of the early settlement of Peoria is comprehensive and well written, a good guide for nonexperts wanting to know more about Illinois' French colonial history. Oddly, though, the seven appendices are nearly as long as the main part of the book, consuming 51 pages. They contain much information that could have been woven into the narrative to illuminate and add context to the facts she assembled. Particularly interesting are journal entries from French explorers describing the natural wonders they encountered in the region. A section on the fur trade and its central role in the struggle for dominance of the territory also is instructive. But, given the lack of historical resources Franke notes at the beginning of the book, her volume is a valuable contribution to the recording of Illinois' early history. Toby Eckert is a Statehouse correspondent for the Peoria Journal Star. Book briefs by Peter Ellertsen Two biographies of famous Illinoisans have been reissued by Southern Illinois University Press. Black Jack: John A. Logan and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era, by James Pickett Jones, is a reprint of a 1967 biography. Logan was a gleefully partisan Democratic congressman from Carbondale and a Union Army general. The book is nearly indispensible for understanding Illinois' role in the Civil War, but in recent years it has been hard to find The foreword by historian John Y. Simon produces new evidence that Logan's decision to support the Union was not easily reached. A hell-for- leather politician who had a master's touch with the common voters, Logan was torn as his section of the state was torn by the outbreak of war. But by summer, he sided with the Union. He resigned from Congress, raised a regiment -— the 31st Illinois — and served with distinction. This biography ends with his election as a gleefully partisan Republican to an at-large congressional seat in 1866. Freedom's Champion: Elijah Lovejoy, a 1964 biography of the abolitionist martyr by U.S. Sen. Paul Simon, has been revised. In the preface, newspaper columnist Clarence Page notes Simon's old-fashioned "virtues of hard work and charity" and says he stands out among politicians as being "refreshingly modest and dull." While it is far from dull, Simon's book is modest and refreshing. In 1964, as a newspaper publisher and state legislator from Madison County, Simon thought readers should know more about the Alton printer who was shot to death in 1837 in a pro-slavery riot. This edition still reflects Simon's concern with such values as courage and public service. The book is vividly written for non-expert readers. Peter Ellertsen teaches English at Springfield College in Illinois. December 1995/Illinois Issues/29

|

|||||||||||||||