|

MEETING ADA DEADLINE CAN BE DIFFICULT

By ROBIN JOHNSON and NORMAN WALZER

In January, 1995, all local governments across the

United States face an important deadline for compliance with the Americans With Disabilities Act

(ADA).

In Illinois, and probably many other states, municipalities will not meet the deadline and some will not be

in compliance for several more years due to cost factors. These were the preliminary findings of a survey of

Illinois municipalities commissioned by the League, the

Local Government Affairs division of the Office of the

Comptroller and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs

(IIRA) at Western Illinois University.

Surveys were mailed to all 1,282 municipalities in

Illinois. As of December 15, there were 406 responses

received for a 31.7 percent response rate. Additional

responses are still being tabulated. Final results will be

available in early 1995. The average respondent population is 9,460. Fifty-five percent of municipalities responding are from metropolitan counties and 45 percent are from nonmetropolitan counties.

The survey gathered information on compliance

efforts by municipalities in Illinois, the associated costs

involved, innovative management approaches and attitudes of municipal officials toward ADA. This article

describes compliance efforts and procedures. Future

articles will describe other ADA compliance issues examined in the survey.

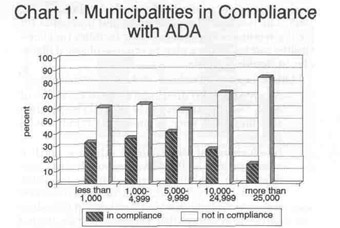

Survey Findings. More than 60 percent of cities and

villages responding report they will not have all structural modifications to municipal buildings and services

completed by January 1995. Compliance rates are

lower in large cities. More than 80 percent of municipalities with a population over 25,000 will not be in compliance (chart 1).

"For most cities and villages in Illinois, especially

large cities, the cost of complying with ADA has prolonged efforts to meet the deadline," said Ken Alderson, Executive Director of the Illinois Municipal

League. "Confusion over the Acts' mandates have also

hurt compliance efforts among small towns."

Large cities are more likely to have a variety of

buildings and services to make accessible. Compliance

will take longer and be more expensive for them. Small

Source: ADA Survey of Municipal Governments, Fall 1994.

|

towns, in many instances, have few, if any, physical

structures to renovate. This may explain the differences

in compliance rates between large and small cities.

The survey listed 18 structures (curb ramps, stairs,

entrances, etc.) involved in making facilities and services accessible. Respondents were asked whether the

structural issue applied to them, their stage of compliance, and whether they were in compliance currently. Overall, 32.4 percent were already in compliance or completed the accessibility projects, with 13

percent reporting the projects almost complete.

Another 22.6 percent believe the elements do not apply

to them. Nearly 16 percent say the review of facilities is

still in progress and 16 percent report little or no action

currently underway. Municipalities are most likely to

have made parking, entrances and corridors and aisles

completely accessible to the disabled.

|

"The results are not surprising. Parking and entrance

accessibility are the most visible and symbolic examples of making services available to disabled people,"

said Vickie Wilson, Program Director of the Coalition

of Citizens with Disabilities in Illinois. "You have to get

into the building before you can access services and

programs."

ADA was enacted in 1990 and prohibits discrimina-

January 1995 / Illinois Municipal Review / Page 11

tion against disabled people in employment, public

services, public accommodations and telecommunications. Under Title II of the Act, all programs, services

and activities provided by local governments must be

made accessible to disabled people by January 26,

1995. The Act provides procedures and timetables for

local governments to evaluate their facilities for accessibility and to create a plan to remove physical obstacles to disabled people.

Other important findings of the survey include:

—Awareness. Most municipal officials are aware of

ADA. Nearly 90 percent of officials responding

said they were very or somewhat familiar with

the Act;

—Involvement of the disabled. About a third of

municipalities in the survey report having residents with disabilities involved in the transition

process. Larger cities are more likely than smaller

towns to include disabled residents. ADA advocates recommend that disabled people have a

role in the process to relate their experiences and

suggest creative and low-cost methods of compliance.

—Prioritization. More than 75 percent of municipalities prioritized the structural changes required

by the transition plan in order of importance.

Priortization was recommended by state local

government organizations as a way to make

compliance more coordinated and efficient.

Municipalities in Illinois have made facilities and

services accessible to the disabled for many years in

response to federal and state disability mandates. On

the federal level, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

of 19731 prohibits recipients of federal funds from discriminating on the basis of handicap. In Illinois, the

Environmental Barriers Act2 requires that newly-constructed facilities, additions to facilities and alterations to facilities meet specific accessibility guidelines.

ADA goes further by creating regulations and standards

for compliance and implementation in existing facilities

and codifying administrative regulations designed to

implement earlier laws.

Most municipalities have made structural changes

as part of ordinary replacement of services and other

programs. For example, under sidewalk improvement

plans, cities can install curb ramps for disabled people

at little or no additional cost. The survey revealed that

municipalities, on average, have completed approximately 35 percent of structural changes as part of ordinary replacement.

Making programs accessible does not necessarily

involve structural changes and increased expenses.

"Reasonable accommodations" may mean simply a

change in policy or providing services and programs at

different locations. For example, Lake Forest officials

moved their City Council meetings to a local school

after a wheelchair-bound citizen could not obtain access to the upstairs council chamber because the building had no elevator.3

According to the survey, the main reason given by

municipalities for not being in compliance is cost, with

nearly 70 percent citing financial considerations. Approximately one in four cities report insufficient time to

comply fully. Larger cities are more likely to cite time

Page 12 / Illinois Municipal Review / January 1995

considerations as a reason for non-compliance. Cost

factors will be explored in more detail in a later article.

In small communities, local officials are less familiar

with the law or may not have the same expertise and

resources available as in larger cities. In some cases, the

law may be seen as vague and an "unfair, unfunded"

federal mandate. Without an attorney or human resource director to advise on how to comply, these

communities may not act as quickly as larger cities.

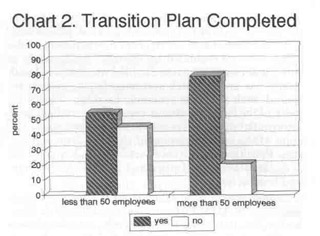

Future Problems? Municipalities that have not followed the process authorized by ADA may face problems in the future. ADA created a compliance process

that includes a self-evaluation and transition plan. The

self-evaluation identifies changes in programs and policies needed to comply with ADA. A committee of

residents from each municipality was responsible for

completing the self-evaluation by January 26,1993. The

transition plan provides a timetable for implementing

recommended structural changes. While local governments had to prepare a transition plan, only those with

|

50 or more employees were required to prepare and

maintain a written plan. Local governments with fewer

than 50 employees, however, were urged to create a

written plan to demonstrate, if challenged, a good faith

effort to comply with ADA.

According to the current survey, nearly 75 percent

of municipalities completed the self-evaluation and

nearly 61.8 percent prepared a transition plan. Only 20

percent of municipalities with more than 50 employees

have yet to complete a transition plan as required but 45

|

Source: ADA Survey of Municipal Governments, Fall 1994.

|

percent of those with fewer than 50 employees have not

completed one (chart 2). Compliance with both requirements varies with size and smaller towns are less

likely to be in compliance than larger cities.

Municipalities that have completed the transition

plan are slightly more likely to be in compliance with

ADA by the deadline according to survey results. Also,

those cities not completing a transition plan were more

likely to view ADA compliance as more difficult than

expected. Municipalities, large and small, that have not

completed a transition plan may face substantial expense if a resident or other group files a complaint.

January 1995 / Illinois Municipal Review / Page 13

The outcome in municipalities that have followed

the process but are not yet in compliance, is less clear.

ADA tries to balance the rights of the disabled and the

rights of those regulated by the Act. The mandate to

provide accessibility to the disabled was tempered with

conditions under which accommodations are not required, such as undue economic hardship. The ambiguity of the language almost ensures that conflicts over

interpretation will necessitate Judicial remedies, despite ADA'S encouragement of alternate dispute remedies. Penalties include court action by individuals, the

U.S. Department of Justice and possible loss of state

and federal funding.

Some courts have taken a rigid stance on compliance with ADA. For example, city officials in Manhattan, KS, planned a $200,000 curb ramp installation

program during a four year period, believing that the

January 1995 deadline was for completing the transition

plan only, not completing the work. A district court

judge disagreed, ruling in July, 1994, that ADA required

all the city's planned curb ramp work be done by the

1995 deadline.4 The decision resulted in three full-time

crews, one part-time crew and contractual employees

working to meet the deadline.

City officials in Philadelphia, PA, interpreted ADA

as requiring curb ramps only when building new streets

or reconstructing streets, not during resurfacing. The

Supreme Court in April 1994 upheld a lower court

ruling requiring the city to install curb ramps on resurfaced streets also.5 Not only must the city install curb

ramps on all streets it plans to resurface in the future, it

must replace curbs with ramps on all streets resurfaced

since January 26, 1992, the date ADA went into effect.

Illinois municipalities not in compliance, but with

transition plans in place, should hope that courts adopt

a more lenient attitude. With many structural improvements completed or in progress, local officials

believe they are making a good-faith effort to comply

with ADA.

Wilson, the Coalition of Citizens With Disabilities in

Illinois director, which has approximately 1,500 members statewide, does not expect a rash of complaints

after the compliance deadline. "We encourage our

members to work with local governments as much as

possible. Complaints to force compliance are used only

is a last resort."

Compliance efforts will continue in most municipalities after the deadline. Officials from towns of less than

25,000 people estimate they will need on average, four

more years to fully comply while officials from cities

over 25,000 in population estimate about five and a half

more years, according to the survey.

While there is visible progress in many communities, such as ramped sidewalk curbs, modified entrances and handicapped parking spaces, much work

remains to be done. Full compliance with ADA will

continue to challenge municipalities for years to

come. •

1. Stephen L. Percy, "The ADA; Expanding Mandates for Disability

Rights," Intergovernmental Perspective, (Winter 1993), pg. 1.

2. Illinois Compiled Statutes, Ch. 410, Section 25/1 et seq.

3. Monica Fountain, "Accessibility Boils Down to Cash," Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1994, pg. 7.

4. David Fleming, "Cities Scramble to Meet Curb Dadline," Peoria Journal Star, August 28, 1994, pg. A10.

5. Ibid.

Robin Johnson is an administrative assistant with the Local Government Affairs Division of the Office of the Comptroller. Norman

Walzer is director of the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs at Western

Illinois University.

14 / Illinois Municipal Review / January 1995

|