|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

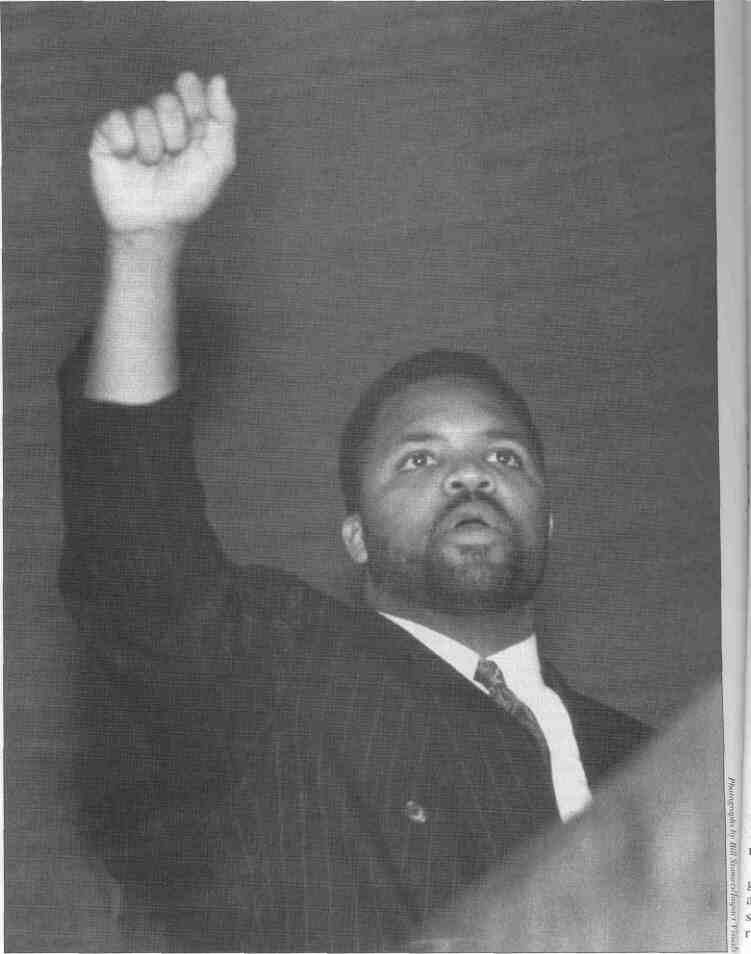

Illinois' newest congressman, Jesse Jackson Jr., rallies supporters at Operation PUSH headquarters in Chicago. Illinois Issues March 1996 | 12 Jesse Junior:

Making a name for himself

Chicago political junkies are already

handicapping the promising newcomer

who defeated a veteran state lawmaker

last winter in the 2nd Congressional

District's special election. They're asking: Could this guy beat Mayor

Richard M. Daley some day? Or is he

just a smooth talker with a famous

name?

For his part, Jesse Jackson Jr. — who surprised Democratic stalwarts

by beating state Senate Minority

Leader Emil Jones Jr. — disavows

interest in the Chicago mayoralty, or

for that matter the U.S. Senate. "I have

no other office in mind besides where

I'm at now," he says. "This is my magnificent obsession."

Yet the 30-year-old freshman congressman, no novice to public life, is

already used to standing on a larger

stage. He has three college degrees,

runs a weekly fax list with 5,600 subscribers nationwide and, in a single

campaign appearance, can skillfully

weave English, Spanish and the language of both the church and the

street into his speech.

And it doesn't hurt that his father,

the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr., ran two

credible campaigns for the presidency.

Jackson Jr.'s high-profile, nationally

honed advocacy skills could benefit his

south Chicagoland constituents. But

first, he'll need to adjust to the slow

pace of acquiring power in Congress,

where the inside track is reserved for

those with years of seniority. Some are

betting this will be his toughest challenge. But veteran South Side political

activist Timuel Black believes the

younger Jackson has the brains and

energy to overcome such frustrations.

Indeed, his political future will depend

on it. 'If he does well for the district,

then the sky's the limit," Black says.

"He's got to produce. And he can."

In fact, Jackson easily won a special

election December 12 to complete the

term of Met Reynolds, who landed in

prison for sexual misconduct. But only

about 20 percent of the eligible voters

in the district bothered to go to the

polls, leading some to suggest Jackson's support is thin. Still, nobody

questions Jackson's savvy in defeating

Jones, an established politician who

had the support of the committeemen

in the district. Jackson used sophisticated voter list software that enabled

him to target the most likely voters

and overcome the low turnout. Now

he's looking ahead. Jackson will have

to run again in this year's regular election cycle, though he's a shoo-in for

the March Democratic primary, where

he's running unopposed. And in a district that's overwhelmingly Democratic

and two-thirds black, presumably he

Illinois Issues March 1996 * 13

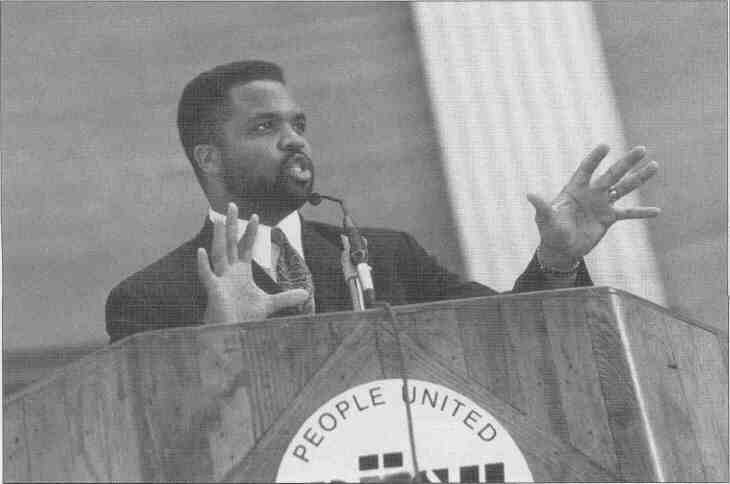

Congressman Jesse Jackson Jr. (above) will have a vote on the U.S. House's Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee. He's angling for a spot on Transportation. Jesse Jackson Sr. holds the mostly ceremonial position as the District of Columbia's "shadow" senator. will be elected in November to his first full two-year term. Unlike Jackson Sr., who rose through the church and cut his teeth as part of the Rev. Martin Luther King's civil rights struggles, the younger Jackson began his activist career by working for labor causes and against apartheid in South Africa. And unlike his father, who holds the mostly ceremonial position as the District of Columbia's "shadow" senator, Jackson will have a vote in the halls of Congress and in the House's Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee. Critics wonder what role the father will play. In fact, three days after his son's primary victory, Jackson Sr. announced he would be moving back to Chicago to retake the reins of Operation PUSH. But outgoing U.S. Sen. Paul Simon says he believes the son has a "bright future" on his own. The Democrat has known Jackson for eight years. "He has the potential to be governor, senator or mayor," he says. Nevertheless, Timuel Black, who led the campaign to register 250,000 voters for Harold Washington's victorious 1983 mayoral run, cautions the freshman congressman not to get ahead of himself. "The problem [Jackson] faces is being in the adversarial role in the present House of Representatives led by arch-conservative Newt Gingrich." Although Jackson wasn't always strong on specifics, during the campaign he stressed his opposition to Gingrich on virtually every issue, including welfare reform, affirmative action and aid to cities. But the issue closest to Jackson's heart is a proposed third Chicago-area airport in rural Peotone south of the city. Despite opposition to the airport from his own party, Jackson supports the proposal. Indeed, Chicago's South Side and the surrounding south suburbs could use a major public works project. The city portion of the district once was home to vast — now shuttered — steel mills that brought middle-class jobs to the area. Today, it's a contrasting blend of vacant industrial land and comfortable bungalows. After the 1990 Census, the district was redrawn to include some of Chicago's south suburbs, ranging from the very poor Harvey to the upper-middle-class Country Club Hills. While 15 percent of the people in the 2nd District live below the poverty line, it also has the highest median income of Chicago's four predominantly minority districts. Although Peotone lies just south of the 2nd District, Jackson says the airport would bring to his district the development that O'Hare Airport brought to the northern portion of the metropolitan area. "Peotone is important because jobs help bring safe neigh- 14 * March 1996 Illinois Issues borhoods. We have a drain of professionals in our community, and we can get them back with jobs," Jackson says. "And the caliber of jobs is important. What's near an airport? You have the tourism industry, you have hotels. You have other industry. You have company headquarters; you have a high level of economic development." The proposal is controversial. Gov. Jim Edgar and Republican legislative leaders support an airport in Peotone. By contrast, Mayor Daley, who had a city-based South Side airport idea shot down in 1992, has been bad-mouthing Peotone ever since. The airlines, who would foot the bill for a new site, are aligned with Daley in the political tussle. Meanwhile, Jackson is angling for a spot on the Transportation Committee so he can push Peotone. Like father, like son. Now that he's in Washington, Jackson is working hard to cut his own path in Congress. A look at his formative years reveals where that path has paralleled, and diverged from, his father's. Both were born in Greenville, S.C. — the younger Jackson on March 11, 1965. He is the second child and oldest son of Jesse and Jacqueline Jackson. Jackson and his father received degrees from North Carolina Agricultural and State University in Greensboro, and attended Chicago Theological Seminary. Both went to the University of Illinois, where Jesse Jr. earned his law degree. But before college, Jackson grew up in Chicago and Washington, D.C., with an influential father who provided a wealth of opportunities and contacts. His parents gave their children the option of attending public or private school, Jackson recalls. He chose the prestigious St. Albans School for Boys in Washington. The school, known for grooming the offspring of the powerful, was where Vice President Al Gore went when his father was a senator from Tennessee. At St. Albans, Jackson went to classes with the children of such major players as Washington Post Publisher Katherine Graham, the ambassador of Saudi Arabia and a number of congressmen, including Rep. Harold Ford of Tennessee. "Many of my peers there are now at the same stage in life that I am," Jackson says, citing an advisor to President Bill Clinton, a friend in the New Jersey statehouse and Harold Ford Jr., who is planning a run for his father's seat. During his adolescence, his brother Jonathan, whom Jackson calls "my most trusted guide," was attending Whitney Young High School in Chicago. At Young, Jonathan went to 15 funerals for his classmates, says Jackson. The two brothers grew close when they went to the North Carolina college together. "I grew to appreciate his history," Jackson says of his 10-month-younger brother. "I learned from him the experience of inner city children." Jackson used this broad educational background in his campaign speeches, jumping from an eloquent explanation of the economic benefits of Peotone to a rhyming rap on why he belongs in Congress. While earning his bachelor's degree in business management, Jackson says, he was most affected by a professor of statistics at A & T. "He made me see the importance of numbers, and I apply that during the budget debates we're going through," Jackson says. "I learned how numbers relate to real people and how the budget will affect them." After graduation, Jackson attended seminary in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. He says he still plans to be ordained some day, that if he hadn't felt the urge to enter politics, he would be a minister. "Ministers see things that politicians don't see," Jackson says. "They christen your baby, bury your child or parent. They're there to pray with you and give comfort if your child is drug addicted or born disabled." The attraction to spirituality clearly reflects his father's influence. But Jackson Sr., who never got a degree from the seminary, chose instead to channel his energies to the church-based progressive movement. Eventually, though, he ran for president — twice. The son, meanwhile, has already made headlines in politics. Yet he still ponders a career in the church. Jackson Jr. graduated from seminary in 1990, and from the College of Law at the University of Illinois in 1993. He doesn't plan to take the bar exam, saying his reason for studying law was as much personal as it was professional. "My [future] wife Sandi was at law school at Georgetown. I was in Chicago. We had been going out," Jackson says. "But I was a little concerned she might meet another guy there. I said I'd go to law school if she would go with me to the University of Illinois." They were married in 1991. Sandra is an attorney and was active in his congressional campaign. Throughout his youth, Jackson was active in causes his father had long been associated with, including voter registration drives and anti-apartheid protests. Jackson Jr. earned national recognition by introducing his father to the 1988 Democratic Convention in Atlanta. In 1990, the two of them, along with Jonathan, were arrested at a protest at the South African embassy in Washington, D.C. Jackson Jr. also joined his father's activist organizations Operation PUSH and the National Rainbow Coalition. Illinois Issues March 1996 * 15

Computer campaign. As is often the case in politics, one man's downfall can mean another's fortune. In the summer of 1995, when 2nd District Congressman Mel Reynolds was on trial for sexual assault, Jackson and his wife were moving into a house in the area. When Reynolds was convicted, Jackson was putting together his campaign team. From the Rainbow Coalition came Frank Watkins, who had worked in Jackson Sr.'s presidential campaigns. The connections made through his father, and his own work in registration drives around the country, helped Jackson Jr. garner $1,000 contributions from members of the Congressional Black Caucus and such noted celebrities as Bill Cosby, Aretha Franklin and Smokey Robinson. About 89 percent of his donations came from outside the district. While money was the cornerstone of the campaign, Jackson also brought a striking new approach to politicking on Chicago's South Side. He contacted nearly every voter by combining high-tech mailings with a high-energy "knock on every door" effort by a throng of dedicated young volunteers. Meanwhile, Jones was content to rely on the remnants of the old Richard J. Daley Democratic Machine to promote his run. The nearly $400,000 Jackson raised for the abbreviated campaign went to voter software from firms in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles that market to candidates nationwide. With the software, Jackson's team was able to categorize constituents who voted in the primary and general elections of 1992 and 1994. These "Four by Four" voters received mailings that stressed that Sen. Jones, recently elected minority leader of the state Senate, could best serve the district by staying in Springfield. A constituent who had voted only once in the last four elections received a mailing that stressed the historic struggle in the black community for the right to vote. Voter data software can also provide a wealth of personal information. So, in a lighter vein, the Watkins-led campaign team sent a congratulatory card on voters' birthdays. Polls taken prior to the primary showed Jackson had close to 99 percent name recognition in the district, a huge advantage in such a short run for office. When the primary returns came in, Jackson had won 52 percent of the Chicago vote and had run nearly even with the 60-year-old Jones in the suburban portion of the district. In the December 12 general election, Jackson easily beat Republican Thomas Somer, an attorney from Chicago Heights. A return match for the two candidates is set for this November. Both are running unopposed in their respective primaries on March 19. Learning the ropes. In December, Jackson Jr. spoke confidently about convening a January meeting in Chicago of 40 young Democratic candidates from across the country to 16 * March 1996 Illinois Issues share expertise on registration, campaigning and get-out-the-vote strategies. But that plan proved overly ambitious. He's been too busy organizing his office and hiring staff. He's also been embroiled in an effort to secure that spot on the Transportation Committee, a move that has turned into a battle between Jackson and fellow Democratic U.S. Rep. William Lipinski, the veteran Chicago politician and Transportation Committee member. Lipinski's South Side district is home to Midway Airport, a cramped but convenient site that experts say could be put out of business by a huge Peotone airport. Lipinski has spent much of his career building the new rapid transit Midway/Orange Line that's helped revitalize the airport. It may not be to Lipinski's or Midway's benefit for Jackson to have a committee slot that provides him the platform to promote Peotone. The issue has forced Jackson to learn quickly how to navigate the halls of Congress.

Jackson walks a tightrope on

endorsements. U.S. Senate candidates Dick Durbin and Pat Quinn want his support. He's also had to maneuver around the potential political land mine represented by campaign endorsements. U.S. Rep. Dick Durbin and former state Treasurer Patrick Quinn are among those vying for the Democratic nomination to replace the retiring Sen. Simon — and for an endorsement from Jackson. Durbin is trying to help Jackson with the Transportation Committee assignment. Quinn did some campaigning for Jackson during the congressional run. Whom do you support? So far, Jackson has remained out of the fray. After all, he's got plenty of other things to keep him busy, including the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's plans to win back majority status in the House. Jackson says he's already met with President Clinton, House Minority Leader Rep. Dick Gephardt and other party leaders to discuss Jackson's help in campaigning for young, black candidates throughout the country. New Jersey Rep. Donald M. Payne, who heads the 39-member Black Caucus, says that group plans to tap Jackson's voter registration skills. Although he's the newest member of the House and one of its youngest, Jackson also has quickly found that sometimes it's best to respond to reporters' questions by not really saying anything. When asked about the possible Daley vs. Jackson Jr. mayoral matchup the pundits are promoting, Jackson is decidedly low-key. "I don't share the rivalry the press seems to have," Jackson says. "I look forward to working with him." * Burney Simpson, who specializes in covering the connection between politics and money for The Chicago Reporter, covered the Jackson campaign for that magazine last fall and winter.

Illinois Issues March 1996 * 17 |

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |