SINE DIE

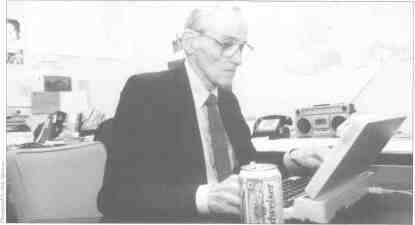

A veteran State house journalist adjourns his political reporting career

The day before James R. Thompson left office as Illinois' longest-serving governor, he invited the four reporters from the Statehouse press corps who had covered his entire 14-year administration to the Executive Mansion for some final reminiscing. One of them was Bill O'Connell, the dean of the Illinois legislative reporters, who began covering the State-house in 1955 during the administration of Gov. William Stratton. "Near the end I asked him, Are you prepared to go?' and he said, 'Yeah, I'm looking forward to it,'" O'Connell says. But First Lady Jayne Thompson joked that her husband would "handcuff himself to the stairs tomorrow" rather than leave. O'Connell recalled the January 1991 incident shortly before his own June 15 retirement as a political writer for the Peoria Journal Star. 22 ¦ July 1996 Illinois Issues "I had the same kind of feeling. I'm prepared to go on to the next phase of my life, but I wondered on the last night of the session. If I could have found those handcuffs I might have used them." For the last 16 of the 41 sessions of the General Assembly Bill O'Connell covered, I was privileged to share an office in the Statehouse Press Room. Most of whatever insights I have gained about the often Byzantine world of Illinois politics I gleaned from Bill and his phenomenal contacts, insights and instincts. This Irish leprechaun from Peoria seemed to be on a first-name basis with every legislator, legislative staffer and lobbyist, as well as several Chicago mayors and U.S. senators. At the office during legislative session days, he would be a one-man wire service, quickly pounding out story after story, often listening at the same time to floor debate piped into the pressroom. At night, holding court at the old Play It Again Sam's saloon across the street from the Capitol, Bill would frequently know what deals were going down the next day on major issues. If it was an issue important to Peoria, sometimes he helped make the deals. Even though he liked to joke that he was a victim of "Anheuser's disease," a reference to the Budweiser he sipped during the day, Bill's memory has always been amazing. On major issues that popped up every session, he could typically recall the year, the bill number and the number of votes it had gotten in committee. I recall one day asking him about a member of the Democratic State Central Committee. Bill listed not only all of the then-22 members and brief anecdotes about each, but all but one of the Republican committee members, as well. In what is increasingly a rarity among both lawmakers and reporters, Bill read many of the bills and could explain them in clearer language than most of the legislative staff. He's an expert on virtually every issue that has come up, from pension bills to annexations by local government, as well as the background of every article in the 1970 state Constitution, the making of which he covered. He could cut through the rhetoric and tell you whether a bill or a plan, to use one of his favorite phrases, was "all gums and no teeth." In 1990, Bill was appointed by his good friend, then state Senate President Philip Rock, to be on a Committee of 100 to make recommendations on whether another constitutional convention should be held. "I wasn't going to go through another constitutional convention. The year I covered both the General Assembly and the Constitutional Convention if I had had a broom up my ass, I could have had three jobs: I could have swept the streets of Springfield going from building to building." In a tribute to Bill delivered in the House in May, Speaker Lee Daniels noted, "We do have an institutional memory in Bill O'Connell...and that's always something that you want to value and to keep in mind, because the memory of how this place operates and some of the intricacies of it and the ins and outs are what help make your profession even better. ..." In fact, Bill used his thorough grounding in his own community to produce a smorgasbord of stories about state politics and government in a writing style intended to appeal to the everyday readers he likes to call Grace and Elmer. They are losing an acute eyewitness to Illinois political history who may be the last of a breed. He was also loyal to them, passing up opportunities to work at larger newspapers or in government. Now, a Statehouse reporter is considered a grizzled veteran at five years, and some reporters seem more interested in winning awards and moving on rather than writing for Grace and Elmer. Bill chose to stick with the nuts and bolts of government reporting. Generally coming to Springfield only during legislative sessions, Bill covered a variety of beats and broke major stories in Peoria that led to changes. A series of articles on how bail bondsmen were posting the same piece of property in several counties to spring clients from jail led to a change in state law. Exposure of a secret campaign war chest established by bankers to help a Peoria mayor spurred an ordinance requiring the toughest campaign disclosure in the state. After Bill discovered another mayor had put a boiler purchased for the city dog pound in his own house instead, giving his old boiler to the pound, voters approved a city manager post. Although he could be testy if someone interrupted him on deadline, Bill was generous in giving advice to pressroom interns in the University of Illinois at Springfield Public Affairs Reporting program, and to the constantly changing parade of reporters in the Statehouse. However, Bill had little patience with the loud Chicago TV reporters who came to Springfield for a day or two and were often unprepared. He leveled sarcastic insults at them and sometimes practical jokes, particularly against the bombastic Hugh Hill of Chicago's WLS-TV. On the closing night of one legislative session, Bill jokingly told Hill lawmakers would turn back the clock to beat the deadline, a practice that had ended several years earlier. Hill, however, rushed the information on the air in a live report. Other Chicago TV reporters who irritated Bill might "lose" the chairs or the mouthpieces of telephones they were using. "When I first came into the picture you had all the guys who were careerists," Bill recalls. "It wasn't just a short stop. It was a reward. People came down here because they had covered city hall and the courthouse and this was the next logical progression in their career. Today it seems it's half interns, and half people who are here briefly and move, or it's 'let the wires do it.' "I know there's a philosophy that you become too familiar with your beat, and I'm probably the perfect example of that. But the idea of bringing in someone new every two years makes it very difficult to build up confidences. And if you don't have confidences, you just can't play." A depth perception problem that kept him from driving helped Bill with those confidences as he commuted to Springfield with members of the Illinois Issues July 1996 ¦ 23 Peoria area legislative delegation. I don't take readership surveys on what you have to do to move a paper. But we had 100,000 subscribers when we had hard news, and we've got 80,000 with soft news, so apparently there's 20,000 people who don't think we have a better product.' When he first came to Springfield in the 1950s, legislative reporters would hit the big hotels at night to glean their next day's stories from the card games and buffets. "The Republicans lived at the Abe Lincoln and the Democrats lived at the St. Nick and the lobbyists and few swing guys in the delegation stayed at the Leland, so if you were an enterprising reporter every night you really had to gallop," Bill recalls. A veteran Peoria lobbyist for Illinois Power took Bill under his wing, and the colorful legislative scene "was pretty heady wine for a kid in 1957." Shortly after he started at the Peoria Star, Bill became the protege of the managing editor. "He gave me all the important beats, and he was determined I was going to be the legislative correspondent or the political writer." That came naturally because his father, Bill O'Connell Sr., was the paper's Kewanee correspondent for several years. Although he threatened to stop writing his political column several times when friends of the paper's publisher complained about Bill's admitted preference for the Democratic Party, he says, "I've never walked in with a chip on my shoulder or the idea I wanted one more scalp on my belt. If the facts are there, the facts are there and you wrote them." Referring to widely published profiles by Ray Long of The Associated Press — another of our former office mates — and Rick Pearson of the Chicago Tribune that highlighted some of Bill's many lobbying successes, he adds: "I hope nobody thinks I spent more time as a community activist than as a reporter because 90 percent of the time I was a reporter. "It's hard to remember a day I didn't enjoy. Not many people are blessed with a career like that," Bill said after the end of the spring session. He was primarily a classic hard-news reporter who could frequently be heard every morning in the Statehouse pressroom giving a tongue-lashing to an editor back in Peoria who had allowed a story Bill considered important to be "overset" or left out of the paper. "I was fortunate for years to have a whole page and [get to] whine because I didn't get more. But today everything is reduced to briefs. I don't take readership surveys on what you have to do to move a paper. But we had 100,000 subscribers when we had hard news, and we've got 80,000 with soft news, so apparently there's 20,000 people who don't think we have a better product." Because of his Irish gift for the funny anecdote and his phenomenal memory, as well as his ability to speak and write in lucid full sentences, Bill has been urged by many to write a book about his experiences covering state government. But so far he has joked that if he did, he would sell the galley proofs page by page to the highest bidders. In the House tribute to Bill, Rep. David Leitch, a Peoria Republican who got his own introduction to the legislature as one of the Journal Star reporters, or "sorcerer's apprentices," helping Bill, added: "And he'll make a whole lot more money, because literally, there is no secret in this town that Bill O'Connell does not know nor have in that extraordinary memory that he possesses." Although he has sometimes been described as the Peoria area's best legislator for helping "facilitate" civic centers, bridges, highways and revenue for parks and museums, Bill almost officially became a legislator about three years ago. He was offered the appointment to a vacant Senate seat, but after several weeks of being addressed around Springfield as "Sen. O'Connell" he decided to turn it down and "go out the way I came in." The only regret Bill expresses about his career is that it took him away from his family for much of many springs. "My wife and my kids have demonstrated amazing patience and sacrifices to let me pursue a career I love." At a reception in Bill's honor at the new state library in May, he gave an emotional tribute to his wife, Helen — St. Helen, as their children refer to her — and one of the stories I have heard him recount most often over the years has to do with her. Helen's birthday is June 22 and until recently that came during a busy part of the spring session. One year Bill forgot and called her on June 25. After he realized his lateness, Helen responded, "I didn't hear from you but Alan Dixon and Mike Howlett [then state treasurer and secretary of state respectively] called on my birthday." After Bill's retirement was announced, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, who credited Bill with first teaching him the ropes as a legislator, sent a proclamation in his honor. U.S. Rep. Dick Durbin of Springfield, former state Attorney General Neil Hartigan and scores of others called. But Bill says he was most touched and surprised by the people who have stopped him in Peoria and congratulated him on his retirement — the embodiments of "Grace and Elmer," the mythical readers he tried to explain state government to for so many years. "I have had all kinds of people stop me on the street or in the bank or in the grocery store saying, 'you've really earned your retirement' or 'we're going to miss reading you,' and I don't know these people from Adam. That's the most satisfying thing of all." Incidentally, with typical puckish wit and perfect timing, shortly before the end of the spring session, Bill finally revealed for the first time Grace and Elmer's last name. "Fudd." Dennis McMurray was Springfield correspondent to the Alton Telegraph from 1978 until the paper's Statehouse bureau was closed in May after 22 years. 24 ¦ July 1996 Illinois Issues |

||||||||||||||

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |