|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

OUR BEST WRITERS

HAVE BEEN INSPIRED BY

THEIR HOME STATE'S

CITIES AND TOWNS AND

PRAIRIES

Essay by Sandra Olivetti Martin

| Read the great writers from anywhere; take your pick. No doubt you'd

be wowed at the literary achievement of New York, Texas or even Alaska.

But Illinois, I can tell you, is special.

Illinois is the state of divine inspiration. Our writers are life-struck lovers, effervescent over what nature or God or humankind hath wrought. They are street-corner preachers, climbing onto their soapboxes to broadcast the apocalypse. They are somber realists, anguished existentialists, conscientious reformers and thrilled lyricists. Regardless of color, creed or sex, of national origin, of outlook pessimistic or optimistic, Illinois writers sing as irrepressibly as canaries, pouring out their faith in a world perfectible. If only they can find the right word. Consider the words of Donald Culross Peattie, prefacing his 1935 biography of naturalist John James Audubon, Singing in the Wilderness: "I wanted to tell of him as all Americans love to tell each other Lincoln stories. Our listeners have usually heard them before but even so, we cannot hold them in; they let something escape from our hearts into the open; they let the winged best of us free." |

|

So who's Donald Peattie? Born in Chicago in 1898, he is one of a scant three dozen on whom Illinois has bestowed its highest literary honors. His name is carved in stone, literally, in a 35-writer band nearly spanning the upper story of the Illinois State Library in Springfield, which opened in 1990. Peattie, who combined his best skills — biography and nature writing — in his story of Audubon, belongs to an even more exclusive society. His is the only repeated name; He shares that distinction with his mother, Elia Peattie.

You say you haven't heard of her? Elia Peattie, who died in 1935, has just given me the gift of the best novel I've read in a year. That's The Precipice, a story of how women strive to balance independence and family life. Peattie's 1914 novel could have been written last year. Or in 1924, '44 or '74. And it still will make sense in 2004.

Elia Peattie is one of six women whose names have been chiseled in Indiana limestone for all to see. Lorraine Hansberry and Gwendolyn Brooks are two of four African-American writers elevated to the top of Illinois' literary pantheon. With them are Richard Wright and Cyrus Colter.

Brooks and Colter are two of the six writers up there who are still alive. The others are Saul Bellow, Studs Terkel, William Maxwell and Ray Bradbury.

22 / December 1996 Illinois Issues

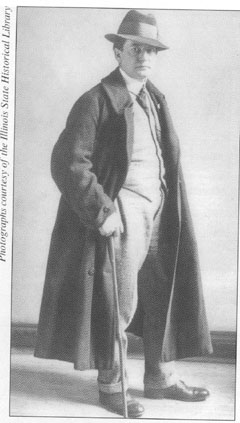

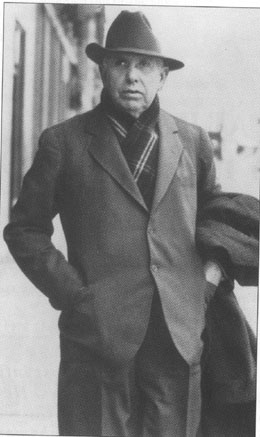

Sherwood Anderson |

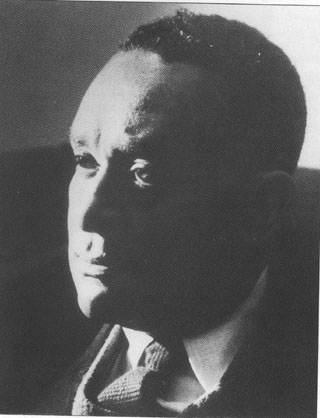

Richard Wright |

Brooks, Illinois' 79-year-old poet laureate, visited the library on which her name is carved just two months ago, to keynote the 1996 Illinois Authors Book Fair.

Homegrown William Maxwell, 88, won the Chicago Tribune's, 1995 Heartland Award for All the Days and Nights, a collection of moving stories, many of which are set in his hometown, Lincoln. Ray Bradbury, 76, made headlines in October as the featured speaker at a science fiction convention in Collinsville and as a favorite interview subject on the Mars rock. Saul Bellow, 81. is a Nobel laureate lively enough to have penned a Democratic Convention- week piece for the Tribune in August.

None of the 35 writers is of Hispanic, Italian or Asian descent. One, Black Hawk, is Native American. Still, they are a study in literary diversity. Which is just what was intended, according to library Director Bridget Lamont.

"We wanted to give a very visible message about the quality of Illinois writing, and we wanted to represent all the regions of Illinois, all the literary genres, women and men, the living as well as the dead." It was Lamont's idea to circle the new library with the names of illustrious Illinois writers. "With hundreds from which to choose, we locked ourselves in a room in downtown Chicago for a day and didn't come out until we had decided," she recalls.

Why 35? Illinois could no more divide its poetic side from its practical than the face of a coin could leap off the back. Thirty-five names used up all the space currently available.

I knew about two-thirds of them. Some were particular favorites: George Ade. whom I'd discovered browsing the shelves of the Lincoln Library in Springfield in the late 1970s and after whom I'd modeled my own early journalism. Nelson Algren and Sherwood Anderson and Edgar Lee Masters and Ring Lardner, who knew (and. with the exception of the cool Lardner, loved) their grotesque characters better than those characters would ever know themselves. Carl Sandburg, who early put the magic of poetry in my life; Vachel Lindsay, who tried to convert Springfield's soul to poetry; and Studs Terkel, who has assigned to himself about the best genre I could imagine: recording the voices of ordinary people.

Others — Edna Ferber, Ray Bradbury, Ernest Hemingway, Theodore Dreiser — were my girlhood and school chums. James Jones wasn't; where I went to school in St. Louis, he was too risque to read. Still others — Richard Wright and Upton Sinclair, Lorraine Hansberry and Gwendolyn Brooks — had opened my eyes and my heart. Lincoln and Black Hawk I'd known as great Illinoisians without thinking of them as writers.

Many of the rest were just names who now insisted on voices.

Who are they? I wondered about these strangers. Are they good, or just good for you? Had the old loves passed or did they live? Most of all, I wondered, what do they think about this state that claims them for its own? I answered my questions by browsing the shelves of the University of Illinois at Springfield library and the Illinois Writers Room in the state library. There are other ways, I've since found. The more famous and contemporary of the writers can be found in any bookstore, while works by many of those who are less known have been reprinted by Vintage Press or by the U of I Press as Prairie State Books.

Illinois writers love their place. Even when they hate it, they love to hate it. Chicago most of all. Carl Sandburg's Chicago is the definitive poem on that city.

Illinois Issues December 1996 / 23

| Jane Addams, 1860-1935

George Ade, 1866-1944 Nelson Algren, 1909-1981 Sherwood Anderson, 1876-1941 Paul Angle, 1900-1975 L Frank Baum, 1856-1919 Saul Bellow, 1915- Black Hawk, 1767-1838 Ray Bradbury, 1920- Gwendolyn Brooks, 1917- Cyrus Colter, 1910- Theodore Dreiser, 1871-1945 Finley Peter Dunne, 1867-1936 Eliza Farnham, 1815-1864 James T. Farrell, 1904-1979 Edna Ferber, 1887-1968 Henry Blake Fuller, 1857-1929 Hamlin Garland, 1860-1940 |

|

Lorraine Hansberry,

1930-1965

Ben Hecht, 1894-1964 Ernest Hemingway, 1899-1961 Robert Herrick, 1868-1938 James Jones, 1921-1977 Ring Lardner, 1885-1933 Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1865 Nicholas Vachel Lindsay, 1879-1931 Edgar Lee Masters, 1868-1950 William Maxwell, 1908- Frank Norris, 1870-1902 Donald Peattie, 1898-1964 Elia Peattie, 1862-1935 Carl Sandburg, 1878-1967 Upton Sinclair, 1878-1968 Louis (Studs) Terkel, 1912- Richard Wright, 1908-1960 |

"I turn once more to those who sneer at this / my city, and I give them back the sneer and say to them: / Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.... / cunning as a savage / pitted against the wilderness ... / Bragging and laughing that under his wrist is the pulse, and under his / ribs the heart of the people."

Maybe Lincoln or Lorraine Hansberry in A Raisin in the Sun wrote better remembered words than those. But nobody better typifies the sense of place.

In his City on the Make, Nelson Algren — he of the sweet sentences telling the bitter experience of being at the bottom of the barrel — celebrated his mixed emotions in much the same high, lyric cadence as Sandburg, though his has a blues rhythm: "Town of the flagpole sitter, iron city, where everything looks so old yet the people look so young.... [of] the ceaseless, city-wide century-long guerrilla warfare between the Do-As-I-Sayers and the Live-and-Let-Livers ... with the brokers breaking in front. ... not that there's been any lack of honest men and women sweating to Jane Addams' hopes here — but they only get two innings while the hustlers are taking four.

"It remains Jane Addams' town as well as big Bill's. ... But it's a rigged ball game."

Theodore Dreiser felt the fatal attraction, too. In Sister Carrie he wrote, "The city has its cunning wiles, no less than the infinitely smaller and more human tempter. There are large forces which allure with all the soulfulness of expression possible in the most cultured human. The gleam of a thousand lights is often as effective as the persuasive light in a wooing and fascinating eye."

Even Saul Bellow, in his 60s, brought near contempt by years of familiarity, could not untangle himself from the city where he discovered poetry, though nearby the "South Branch of the river, you remember, was Bubble Creek because the blood and tripes and tallow, the stockyards' shit, made it bubble in the summer." He wrote in The Dean's December: "I'm attached to Chicago."

When Bellow was young — The Adventures of Augie March was published in 1952 when he was 37 — that passion burned brightly. Other writers love Chicago for its sprawl or its machinery, but Bellow loved it most, it seems, for the human mass drawn to its thousand lights: "Children of immigrants from all parts, coming up from Hell's Kitchen, Little Sicily, the Black Belt, the mass of Polonia, the Jewish streets of Humboldt Park. ... In the mixture there was beauty — a

24 / December 1996 Illinois Issues

Jane Addams |

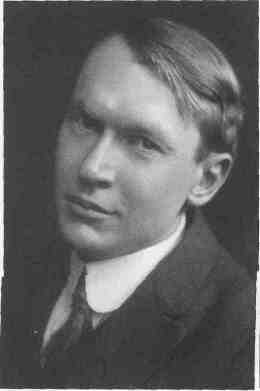

Vachel Lindsay |

good proportion — and pimple-insolence, and parricide faces, gum-chew innocence, labor fodder and secretarial forces, Danish stability. Dago inspiration ... an immense sampling of a tremendous host, the multitudes of holy writ, begotten by West moving, factor-shoved parents."

Love of the human bazaar that makes up Chicago is as common a theme as the city's allure. Feeling that love, some of Illinois' writers crusaded to correct the crush of social ills that was also their city. Upton Sinclair wrote novel after long novel to dramatize "the furies of greed and hate" in hopes of provoking outrage and reform. In The Jungle (1906), he took on Chicago's meat packing industry and had some of the success he hoped for, though the changes did more for food safety than for the workers he championed.

Reformer Jane Addams chronicled her work among the immigrants who thronged to the city, winning a place among the Illinois 35 for the stories she told. One of the many inspired by Addams' crusade was novelist Elia Peattie, whose heroine in The Precipice, Kate Barrington, joins Addams in teaching the city to be a good family: "A city, she maintained, was a great home. She demanded, then, to know if the house was made attractive, instructive, protective. Was it so conducted that the wayward sons and daughters, as well as the obedient ones, could find safety and happiness within it? Were the privileges only for the rich, the effective, and the out- reaching?"

Other writers loved the city for itself alone. So great is the fascination that generation after generation of writers have rushed into the city's streets to rub shoulders with their inspiration. That's where George Ade found his "Stories of the Streets and the Town." Journalist Ade, who wrote those Chicago Record columns during the last decade of the 19th and first of the 20th century, was so wrapped up in the world around him he bragged that his type compositor never needed to reach for the capital I.

A dozen years later, the same Circe sang to Ben Hecht, who dashed into the streets for inspiration for A Thousand and One Afternoons in Chicago and convinced his editor, Henry Justin Smith, that he would for one year faithfully record what he saw in his column for the Chicago Daily News. Hecht's "Big Idea," wrote his editor, "was that just under the edge of the news as commonly understood, the news often flatly and unimaginatively told, lay life; that in this urban life there dwelt the stuff of literature, not hidden in remote places, either, but walking the downtown streets, peering from the windows of skyscrapers, sunning itself in parks and boulevards. ... His was to be the lens throwing city life into new colors, his the microscope revealing its contortions in life and death."

In our time Circe sings to Studs Terkel, who has adopted a style for our times, capturing people's living words on tape and transcribing them in his books of city life in the last half of the 20th century. Studs Terkel is a man so much in step with Chicago's literary tradition that he changed his given name, Louis for the name of a fictional Irish street thug.

Studs Lonigan, the selfconsciously tough brainchild of the prolific James T. Farrell, took his strength from the city, too: "Studs Lonigan, looking tough, sat on the fireplug before the

Illinois Issues December 1996 / 25

Lorraine Hansherry |

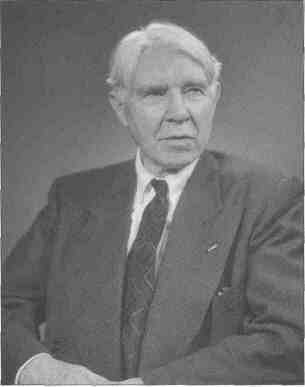

Carl Sandburg |

drug store on the northeast corner of Fifty-Eighth and Prairie. ... People paraded to and from along Fifty-Eighth ... Studs vaguely saw the people pass, and he was, in a distant way, aware of them as his audience. They saw him, looked at him, envied and admired him, noticed him, and thought that he must be a pretty tough young guy."

James T. Farrell, of course, is another name carved in stone.

Yet the polyglot masses that make the city great despise one another. Farrell records, for example, that the Irish hated the Jews. "Davey Cohen, Tommy Doyle, Haggerty, Red Kelly and Killarney happened along. Killar- ney had a pepper cellar, and they went over to the park to look for Jews and throw pepper in their eyes."

Negroes remained slaves in the South, as you read in Richard Wright's undimmed 1942 autobiography, Black Boy: "I could calculate my chances for life in the South as a Negro fairly clearly now. I could fight ... I could submit... I could drain off my restlessness by fighting with others with a black skin [or]... I could forget what I had read and find release from anxiety and longing in sex and alcohol."

Yet Chicago, the end of the pilgrimage made by thousands of African Americans, offered more oppression. In 72 Million Black Voices, Wright's history of his race in America, he describes the city's "prison: our death sentence without a trial, the new form of mob violence that assaults not only the one individual, but all of us, in its ceaseless attacks.... The kitchenette, with its filth and foul air, with its one toilet for thirty or more tenants ... scatters death so widely among us that our death rate exceeds our birth rate, and if it were not for the trains and autos bringing us daily into the city from the plantations, we black folks who dwell in northern cities would die out entirely."

Richard Wright is another name carved in stone.

Hatred as practiced and experienced among races and nationalities gives Illinois writers another great theme. Injustice so inhabits the world of Illinois writers that one, Lorraine Hansberry, she of A Raisin in the Sun, claimed it was impossible to divide the artist from the social critic.

So apparently, thinks Cyrus Colter, another name carved in stone. Colter retired from what University of Illinois English professor James Hurt in his official biography for the state library calls a "distinguished career as a Chicago attorney and a commissioner of the Illinois Commerce Commission" to describe the war of the races in painfully existential novels:

"And look happy, will 'ya? Don't forget what I've told you agin and agin — they always expect us to be happy! Don't ask me why — I'll be Goddamned if I know. But they do. We ain't got a pot nor a window, but we're supposed to be happy!" writes Colter in The Hippodrome.

Chicago has no monopoly on injustice, according to Illinois writers. Writers of town and prairie know it too. Even the gentle William Maxwell conspired in the inequality between "The Front and the Back Parts of the

26 / December 1996 Illinois Issues

Theodore Dreiser |

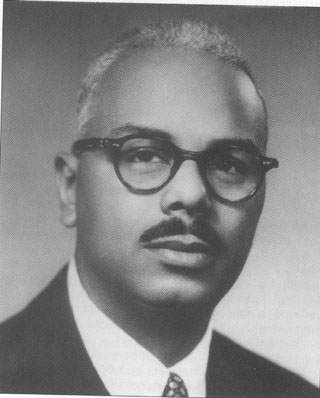

Cyrus J. Colter |

House." With all good will, he presumed upon and fictionalized the lives of the black servants in his childhood household. That the injustice of his 1991 story, from the collection All the Days and Nights, is cut to domestic scale makes it the more familiar.

Nor is difference of nation or of race the only scourge Illinoisans use to beat one another. As Edgar Lee Masters or Sherwood Anderson remind us, any difference will do.

Yet just as the city is bigger and better than its worst in the tales of Illinois writers, so is the state. On many, the land cast a spell. "It is not a fond looking back to youth days that keeps me enchanted," writes Edgar Lee Masters in The Sangumon (1942), his personal history of that central Illinois river. "It is magic in the soil, in the plains, the borders of forest, the oak trees on the hill."

Hamhn Garland, who chronicled in personal narrative the nation's great change to an industrial economy, believed that agricultural America bred a race of heroes. "The men and women of that far time loom large in my thinking for they possessed not only the spirit of adventurers but the courage of warriors. Aside from the natural distortion of a boy's imagination I am quite sure that the pioneers of 1860 still retained something broad and fine in their action, something a boy might honorably imitate," he wrote in A Son of the Middle Border (1917).

All the spirits seem to Masters to enrich nature's gift, so that the land had the power of a medium: "I am sure that if you should drive through Menard County," he writes, "strange dreams would come to you, and, moreover, those dreams would tally with mine. If so, does not something float out of that soil, are not the past people of this region double-lived?"

Keep reading, and Illinois writers tell you that bounty stretched from Indian times to pioneer to village, even to our day.

William Maxwell, who edited The New Yorker for 40 years, found inspiration in little Lincoln, his hometown: "Three-quarters of the material I would need for the rest of my writing life was already at my disposal. My father and mother. My brothers. The cast of larger-than- life characters that I was presented with when I came into the world. The look of things. The weather. Men and women long at rest in the cemetery but vividly remembered. The Natural History of home."

It stands to reason that the muse and you and I are neighbors, too.

This is, of course, what I expected Illinois writers to tell me. Perhaps because I became a writer in Springfield, I've felt kin to Vachel Lindsay, who threw himself on the mercy of the land like a beggar with perfect faith in plenty. He dedicated A Handy Guide for Beggars, his handbook on meeting inspiration where you find it, to the "one hundred new poets in the villages of the land."

With the growth of Illinois' population since Vachel's time, today there are probably many more inspired writers in city, town and fertile prairie. If you've looked at the unfinished east side of the Illinois State Library, you'll see the open space where their names will someday be carved in stone.

As an Illinois writer herself, Sundra Martin was a founder of Brainchild, the women 's writing collective. These days, she publishes New Bay Times, a regional weekly in Maryland covering the Chesapeake Bay. She dedicates this article to Illinois librarian Florence Lewis.

Illinois Issues December 1996 / 27

| Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator

Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digitial imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |