"No buffalo ranging across the prairie, no deer starting through the forests, no bird interrupting the solemn stillness which uniformly reigns aver the country." William Keating penned this observation in "Expedition to the Source of St. Peter's River," made in 1823. In writing about the excursion across the Midwest, which included northern Illinois, Keating repeatedly noted the scarcity of wildlife, especially large game animals. Just 150 years after Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet—the state's first European explorers—traveled the Illinois and Mississippi rivers, Keating observed that once abundant wildlife species were vanishing from the Prairie State. Illinois has lost a host of animal species since it became a state in 1818. No longer does it support black bear, elk, bison, gray wolf or mountain lion. Gone are such other native species as white-tailed jack rabbit, porcupine and dozens of species of freshwater mussels. Many fish species have been extirpated—they no longer occur— in Illinois. These include the alligator gar, the blackfin cisco and several types of darters and shiners. Birds that used to breed in Illinois no longer do. The whooping crane, the common loon and the trumpeter swan are among them, as are species which are now extinct: the ivory-billed woodpecker, the Carolina parakeet and the passenger pigeon. "Extinction is a natural process," says Sue Lauzon, executive director of the Illinois Endangered Species Protection Board. "But human activities have significantly accelerated its rate." Natural processes did not cause the extinction of the passenger pigeon. Rocks migrated through Illinois in massive numbers in the 1800s, searching for food and cover after northern forests of beech and other hardwoods were cleared for farm land. Noted American ornithologist Robert Ridgway, born in 1851, described a boyhood sighting of passenger pigeons along the Wabash River at Mount Carmel. "I can well remember the enormous flights of these birds," he said in a Throughout history Illinois wildlife species have been disappearing because of the influences of human civilization

52 * Illinois Parks & Recreation * March/April 1996

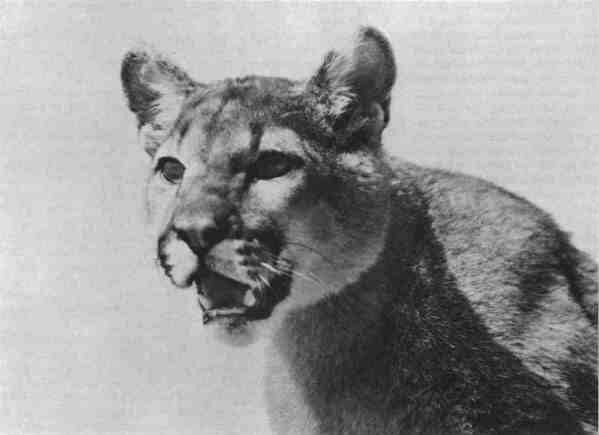

The mountain lion has been extirpated from Illinois since about 1800. Though once indigenous to the state, the only place to see an elk in Illinois now is in a zoo.

Illinois Parks & Recreation * March/April 1996 * 53

1926 article, "and recall one that extended completely across the sky from horizon to horizon, the noise of their wings sounding like distant thunder." Other observers, including E.S. Ricker in Iroquois County. Nelson McFarland in Brown County and Christian Schultz in Alexander County, reported how the pigeons would roost in such numbers that their weight would cause tree limbs to break. Throughout the 19th century, passenger pigeons were killed commercially for meat, as nuisances and for sport Loss of habitat confined the birds to ever-diminishing forests, leading to malnutrition and resultant disease. Attempts were made to breed captive birds, but they failed. By the 1870s, the species had virtually disappeared in Illinois, although sightings were reported until about 1911. The last known passenger pigeon died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. With the extinction of the Carolina parakeet, or "paroquet" as C.R Gilman spelled it in 1835, Illinoisans would no longer catch a glimpse of the colorful bird along tree-lined riverbanks. "They present a most beautiful appearance when on the wing," wrote Gilman, "their green plumage glittering in the sun beams." So many Carolina parakeets were destroyed because of crop depredation or were captured as pets that by the mid- to late-1800s, they no longer existed in Illinois. By 1901, they didn't exist anywhere. Why settlers and their descendants exploited the animals that inhabited America likely was due, in part, to their European heritage, in which wildlife was the property of nobility and commoners were severely penalized for illegal hunting. With no restrictions in their new country, market hunters, trappers and pioneers took advantage of what seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of wildlife. During his 1823 excursion, Keating noted that while American Indians chiefly subsisted on bison, commonly called buffalo, "it must likewise be remembered that it is characteristic of the Indian never to destroy more than he can consume, in this differing much from the white hunter, who will frequently kill a buffalo for its tongue or its marrow bones, leaving the rest of the animal as a prey to the wolves. In the destruction of the buffalo, the white man cannot even plead the inducements of trade, since a great many are killed whose hides are never turned to use." Keating observed that Native Americans, too, began to take wildlife indiscriminately after seeing white hunters waste the game the Indians had wisely managed for centuries. John White of Ecological Services in Urbana says Keating thought they had given up on their earlier conservation ethic.

"Keating speculated the Indians saw what was happening and believed they didn't have anything to lose," White says. In addition to game being taken beyond that which was needed for use as food or clothing, Illinois wildlife experienced further declines in the early to mid-1800s as homesteaders cut the forests and plowed the prairies, destroying native habitat. One species that appeared to escape huge population losses was the white-tailed deer. Whitetails no longer were preyed upon by wolves or mountain lions, which had relocated north and west of Illinois, and they easily adapted to land converted to farming. However, by the middle of the 19th century, unregulated market hunting also had taken its toll on whitetails. The Illinois General Assembly recognized that—as with elk, bear and bison—the supply of white-tailed deer was not inexhaustible. In 1853, it passed a law prohibiting deer hunting, as well as hunting for prairie chicken, quail, woodcock or partridge, in 16 mainly northern Illinois counties for the first six months of each year. Although it proved to be ineffective—deer numbers decreased to such an extent that whitetails were all but wiped out of the state by 1910—it is recognized as Illinois' first game law. Today, Illinoisans rely on a variety of measures to help maintain viable wildlife and fish populations, prevent future losses and re-establish species that once existed in the state. A Fish Commission authorized in 1879 and a Game Commission established in 1903 made early attempts to regulate and manage the state's fish and wildlife resources. The commissions joined forces in 1913, and in 1925 became part of the Department of Conservation, the forerunner to today's Department of Natural Resources.

54 * Illinois Parks & Recreation * March/April 1996

Hunting licenses have been required in Illinois since 1903 and fishing licenses since 1923, with revenue used to enforce seasons and limits. Through wise management, game species that once were scarce or absent have made successful comebacks—wild turkey, beaver and whitefish among them. White-tailed deer, which could not be legally hunted in the state from 1901 to 1957, are now abundant in Illinois woodlands, river bottoms and scrub lands, and, yes, in its corn and bean fields. Last fall's firearm deer harvest totaled more than 105,000. In addition to game management concerns, non-game wildlife needs also have been addressed in Illinois. In an effort to halt the loss of animal species from the state, the General Assembly passed the Illinois Endangered Species Protection Act in 1972, a year before Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, now up for re-authorization. Illinois' first lists of endangered and threatened animals were adopted in 1980, and have been periodically revised, most recently in 1993-94. A species with a sustaining population in Illinois is classed as endangered if it is in danger of becoming extinct throughout all or a significant portion of its natural range. It is listed as threatened if it is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future. Listing a species gives it legal protection from being taken or destroyed. The executive director of the Endangered Species Protection Board says the group constantly gathers information to identify which species are in trouble. "Because the Department of Natural Resources is entrusted to oversee the state's wildlife on both public and private lands, the board advises the Department on ways of preserving species," says Sue Lauzon. "Our goal is to get species recovered." Endangered species that have benefited from the board's work include the peregrine falcon and the river otter, both beneficiaries of Wildlife Preservation Fund backing. Following reintroduction efforts a decade ago, pairs of peregrines now nest amid downtown Chicago skyscrapers, with other sightings sometimes made elsewhere in the state. Currently, the Wildlife Preservation Fund is being used to bring river otters back to the Illinois, Wabash and Kaskaskia river basins. (Individuals wanting to make a tax-deductible donation to the Wildlife Preservation Fund can do so by designating an amount on line 15a of the IL-1040 income tax form or line 7a of the IL-1040EZ simple form.) Lauzon believes government needs to look beyond economics whenever biological diversity is at stake. "Government exists for the good of all," she says. "We as citizens have a right that the wildlife, which we all own, will be protected." Just as the death of a canary taken into a coal mine is a warning to miners that the air is deadly, wildlife is one of the best indicators of an area's, and ultimately the planet's, biological health. Because of the interrelationships among all living things, the warnings from passenger pigeons, Carolina parakeets and other "canaries" should not go unheeded. Anne Mueller is a staff writer for Outdoor Illinois, a publication of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Illinois Parks & Recreation * March/April 1996 * 55 |Home|

|Search|

|Back to Periodicals Available|

|Table of Contents|

|Back to Illinois Parks & Recreaction 1996|

|

|||||||||||||||