SPECIAL LEGAL FEATURE

Supreme Court Confirms Park District Immunity for Swimming Pool Drowning by James D. Wascher In order to minimize exposure to tort liability for drownings and other aquatic injuries, park districts and forest preserve districts should follow a few simple rules. The Illinois Supreme Court recently ruled that park districts, forest preserve districts and other units of local government are immune from liability for injuries, including drownings, that occur during the posted hours of swimming pools, beaches, and other aquatic facilities, so long as they provide supervision during the posted hours. Prior to the Supreme Court's April 18 decision in Barnett v. Zion Park District [Docket No. 78161], drownings and nonfatal submersion injuries, or "near drownings," were perhaps the single greatest source of potential legal liability for park districts and other units of local government. In Barnett, however, the Supreme Court held that, under Section 3-108(b) of the Local Governmental and Governmental Employees Tort Immunity Act, units of local government have "unconditional immunity [from] liability when supervision is provided" at an aquatic facility. Section 3-108(b) provides that: "Where a local public entity or public employee designates a part of public property to be used for purposes of swimming and establishes and designates by notice posted upon the premises the hours of such use, the entity or public employee is liable only for an injury proximately caused by its failure to provide supervision during the said hours posted." The Supreme Court rejected the plaintiff's argument that all provisions of the Tort Immunity Act, including Section 3-108(b), contain an implied exception allowing liability for willful and wanton conduct. Writing for a 5-2 Supreme Court majority. Justice Charles E. Freeman of Chicago declared that, "The plain language of section 3-108 is unambiguous. That provision does not contain an immunity exception for willful and wanton misconduct. Where the legislature has chosen to limit an immunity to cover only negligence, it has unambiguously done so [in other sections of the Tort Immunity Act]. Since the legislature omitted such a limitation from the plain language of section 3-108, then the legislature must have intended to immunize liability for both negligence and willful and wanton misconduct." The decision in Barnett arose from the drowning of 10-year-old Travis King in the Zion Park District's Port Shiloh swimming complex on June 9, 1990. The Park District submitted evidence to the Circuit Court for the 19th Judicial Circuit in Lake County demonstrating that it had posted 11 American Red Cross-certified lifeguards at the pool complex, which consisted of three swimming pools, including the "deep pool" at which the accident occurred. The deep pool had 3,375 square feet of water surface area. There were no more than 170 bathers in the pool at the time of the accident. The Illinois Department of Public Health's (continued on page 16) Illinois Parks & Recreation • July/August 1996 • 15 Swimming Pool and Bathing Beach Code requires swimming pool operators, including park districts and forest preserve districts, to provide lifeguards at a ratio of 1 per 200 bathers, or 1 per 2,000 square feet of water surface area, whichever is less. The Zion Park District had posted six lifeguards at the deep pool at the time of the accident, and therefore exceeded guard quota set by the Code. The Supreme Court's decision emphasized that "the District satisfied state public health regulations in terms of the number of lifeguards present and their qualifications." The plaintiff alleged that the park district's lifeguards did not provide adequate supervision of the deep pool. One witness for the plaintiff claimed that she had seen Travis struggling in the water within her arm's reach. She testified that she did nothing other than to tell a lifeguard about the boy. Another witness testified that this woman actually was sitting in her car outside the pool complex at the time of the accident, and therefore could not possibly have seen and done what she said. Yet another witness gave a completely different account of how Travis got into trouble in the water, and testified that a lifeguard whom he alerted had retrieved Travis from the water. In fact, it was another pool patron who brought the boy to the edge of the pool, where lifeguards removed him and performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation. All six of the park district's lifeguards testified that they were actively monitoring the swimming pool, and saw nothing out of the ordinary involving Travis or any other patron. The plaintiff in Barnett argued that the mere presence of lifeguards was insufficient to establish immunity under Section 3-108(b) and that some minimum level of competence or active control over the swimming facility was required. The Supreme Court disagreed. The plaintiff "'attempts to apply a substantial limitation on the immunity of section 3-108(b) where none exists,'" the Court stated. "The plain language of section 3-108(b) unambiguously does not require any particular level or degree of 'supervision.' The legislature omitted from the plain language of section 3-108 any reference to the quality of supervision required thereunder. Thus, the legislature must have intended to provide unconditional immunity [from] liability when supervision is provided." This holding applies not only to Section 3-108(b) of the Tort Immunity Act, which relates to aquatic facilities, but also to Section 3-108(a), which provides that "neither a local public entity nor a public employee is liable for an injury caused by a failure to supervise an activity on or the use of any public property." Section 3-108(a) immunity extends to a broad range of activities on public property concerning which a plaintiff might claim that a park district or other unit of local government failed to provide supervision, or provided supervision in a fashion constituting negligence or even willful and wanton conduct. Two years ago, the Illinois Appellate Court for the Third District had ruled in Blankenship v. Peoria Park District [269 Ill. App.3d 416, 647 N.E.2d 287 (3d Dist. 1994)] that Section 3-108(b) did not immunize the Peoria Park District from liability where an adult swimmer drowned allegedly while alone in a park district swimming pool. Three park district lifeguards were in the pool area, but allegedly were in "a small room adjacent to the pool where they were unable to see the pool." The Appellate Court held that, since the lifeguards "were not in a position to observe the pool," their conduct "was not mere inattention or a momentary lack of vigilance, it was a complete absence of supervision." The court therefore ruled that Section 3-108(b) did not apply, and reversed the dismissal of the plaintiff's complaint. The Supreme Court cited the Blankenship decision with approval in Barnett. "This case is distinguishable from Blankenship," the Supreme Court declared. "Here, the District provided lifeguards, as state public health regulations prescribe, who were not only physically present, but were actually supervising the deep pool." Justices Moses W. Harrison, II of Fairview Heights and Mary Ann McMorrow of Chicago dissented from the Supreme Court's decision in Barnett. The practical effect of Barnett and two other recent Supreme Court decisions, Mt. Zion State Bank & Trust v. Consolidated Communications, Inc. [169 Ill. 2d 110,660 N.E.2d 863 (1995)] and Bucheleres v. Chicago Park District [Docket Nos. 78760 and 78790] (discussed in Part 1 of this article) will be to shield park districts and forest preserve districts from liability for the vast majority of drownings and other aquatic injuries. Barnett extends sweeping immunity from liability for swimming and diving accidents at designated aquatic facilities during posted hours, as long as the district provides supervision. Mt. Zion and Bucheleres hold that property owners generally owe no duty to protect swimmers and divers from injury at all times when aquatic facilities are closed and at all locations where swimming and diving are never permitted. Of course, it is always possible that a future Supreme Court majority may adopt the reasoning of the two dissenters in Barnett, and substantially narrow the applicability of Section 3-108(b) immunity, or that the General Assembly may accept the Barnett majority's suggestion that Section 3-108(b) should be amended to reduce the protection it affords to park districts and forest preserve districts. The Illinois Association of Park Districts (IAPD), the Chicago Park District and the Illinois Governmental Association of Pools (IGAP) jointly filed an amicus curiae ("friend of the court") brief in support of the Zion Park District's position in the Supreme Court, as did the Chicago Board of Education and the Cook County Forest Preserve District. IAPD, IGAP, the Illinois Municipal League, the Illinois Association of School Boards and the Institute for Local Government Law also jointly filed an amicus curiae brief in support of the Chicago Park District's position in Bucheleres. This unprecedented level of intergovernmental cooperation certainly contributed to the Supreme Court's positive reception of the defendant park districts' arguments in both cases. 16 • Illinois Parks & Recreation • July/August 1996 In order to minimize their exposure to tort liability for drownings and other aquatic injuries, park districts and forest preserve districts should follow a few simple rules: • The district should officially designate for use for purposes of swimming all pools, beaches and other bodies of water at which it intends to permit swimming, and the hours of permitted use. This designation should be made by ordinance, resolution, rule or regulation. • The district should adopt an ordinance, resolution, rule or regulation prohibiting any person from entering or remaining in the water (not just swimming or diving) at all other times and for all other bodies of water. Section 3-102(a) of the Tort Immunity Act provides that a unit of local government has a duty to maintain its property in a safe condition only for persons "whom the entity intended and permitted to use the property." The courts have held that this duty does not apply to persons using public property in a manner prohibited by ordinance. • At each facility that the district has designated for use for purposes of swimming, it should post a notice stating the hours that the facility is open for swimming. The notice should be placed conspicuously, perhaps at the main entrance to the swimming pool or other swimming facility. • The district should provide lifeguards to supervise all of its swimming facilities during all hours that they are posted as open to the public. • As required by the Illinois Department of Public Health's Swimming Pool and Bathing Beach Code, the district should ensure that each lifeguard has received current training and certification from "the American Red Cross, YMCA, or equivalent." The Department of Public Health announced in 1994 that it accepts training and certification by Jeff Ellis & Associates, Inc. as "equivalent" to training by the Red Cross or YMCA. • The district should carefully monitor the number of bathers in its swimming pools, so that, at all times, there is one lifeguard for every 200 bathers, or one lifeguard for every 2,000 square feet of water surface area, whichever is less. • The district should require all bathers, including experienced swimmers, to get out of the water if the lifeguards must leave their posts for any reason. • At locations where the district knows that persons are frequently diving into shallow water, or water containing subsurface obstructions such as rocks, debris or even sandbars, the district should post signs that both prohibit diving and, in the words of Section 3-109 (b)(2) of the Tort Immunity Act, give "reasonable warning as to the specific dangers present." For example, a warning sign might read "Danger—Shallow Water—No Diving—May Cause Serous Injury." These measures should not only protect park districts and forest preserve districts from legal liability for drownings and other aquatic injuries, but should help to prevent such incidents from even occurring. Of course, immunity from liability is no substitute for a thorough and effective loss control program. James D. Wascher is an attorney with the Chicago law firm of Friedman & Holtz, P.C. He was lead counsel for the Zion Park District in the Barnett case and for the Chicago Park District in the Bucheleres case, and argued both cases before the Illinois Supreme Court.

Part 1 of this article appeared in the May/June 1996 issue of

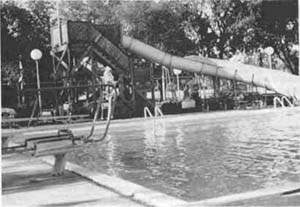

Illinois Parks & Recreation. Photo: The "deep pool,"

scene of the

accident in Barnett v. Zion Park District. The Illinois Association of

Park Districts (IAPD) co-sponsored "friend of the court" briefs in

support of the park district defendants in both Barnett and Bucheleres.

IAPD's participation was instrumental in winning two major victories for

park and forest preserve districts.

Illinois Parks & Recreation • July/August1996 • 17 |

||||||||||||||