Keeping Our Parks a Safe Place to Play by Harry E. Carlile, Jr. Whether you call them park police officers, conservation police officers, or ranger police, they all have one mission: keeping our parks a safe place to play. Recently the need for park district law enforcement officers in Illinois and across the country has come under fire. The debate surrounds the questions, who are these officers and what do they do? Critics claim they are a waste of money and should be eliminated since they duplicate the services already provided by other local law enforcement agencies. Advocates claim park policing is a specialized type of law enforcement which requires knowledge, training and experience above and beyond that of a regular law enforcement officer. Who is right? To effectively answer this question it is beneficial to learn some background information about park district policing. Who are these officers? How arc they selected? How arc they trained? What do they do? How many are there? These are just a few of the questions we will examine in this article.

History of Park Police

Pleasure Driveway and Park District of Peoria was voted into existence. Peoria hired its first police officer, S.L. Gill, on August 7, 1895. Finding a need for more law enforcement in the parks at night, the district hired Samuel Neff on September 11, 1895. Larger cities such as Chicago and Decatur also began forming park district police departments during this time. Even smaller park districts like Dolton (established 1929) formed their own police departments. Since those early years many park districts have formed police departments. Others—depending upon

The Peoria Park District Police Department (summer 1898) photographed in front of the Palm House in Glen Oak Park. Left to right: Jas Elsen, W.H. Donahue, Henry Oeldrich, W.W. Malonly and J.W. Meredith. Illinois Parks & Recreation • September/October 1996 • 19

Park districts, forest preserve districts and conservation districts cannot just appoint police officers and form police departments. They first must have the authority to do so granted to them by the state legislature. For each of the types of districts listed above, legislation for the appointment of police officers appears in their respective codes. For park district police departments, the enabling legislation has been around since the formation of the first districts and now can be found in 70 ILCS 1205/4-7 (hiring of police officers) and 70 ILCS 1325/1 (arrest powers). Since 1894 there have only been three significant changes to the law as it pertains to park district police departments. The first occurred in the early 1930s, adding language to the code that defines the arrest powers of park district police. The second addition occurred during the 1960s and allows a park district to tax specifically for the organization and maintenance of a park district police department. In June of this year Governor Edgar signed into law Public Act 89-458 which essentially clarifies statutory language written in the 1930s. These changes "clean up" the language of the statute and make it easier to interpret. It also clarifies the jurisdictional powers of park district police. This legislation was developed by the Illinois Association of Park Districts (IAPD) in consultation with the Illinois Park Law Enforcement Association (IPLEA) and was welcomed by the professional park law enforcement community.

Park District Police Today

Qualifications

Once these qualifications are met, the district usually uses a stringent testing process to ensure the best applicant gets the position. This process includes a written exam, physical agility exam, interviews, a battery of psychological exams, and a background investigation. Currently there is a large pool of highly qualified individuals seeking law enforcement positions. The Peoria Park District recently received more than 60 qualified applicants for one full- time patrol officer position.

Training

After successfully completing the academy and passing the certification examination, most park district police officers return to their agencies where they must prove themselves by successfully completing a two- to three-month certified Field Training Officer (FTO) program. If successful with the FTO program, the officer usually must complete additional training in conservation law enforcement, hands-on driving skills, and 20 • Illinois Parks & Recreation • September/0ctober 1996 other areas that are not covered at the academy. Finally, the recruit must successfully complete a probationary period of at least one year. Then and only then do most park law enforcement agencies feel an officer is qualified to work solo in their parks. However, the learning does not stop there for park district police officers. Most park law enforcement agencies require more education and training than their non-park district counterparts. Park police start out with more and continue to receive more training throughout their careers in park law enforcement

Duties

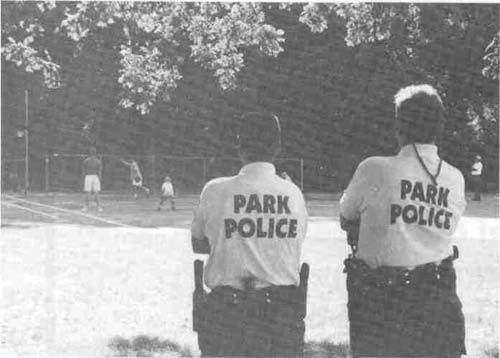

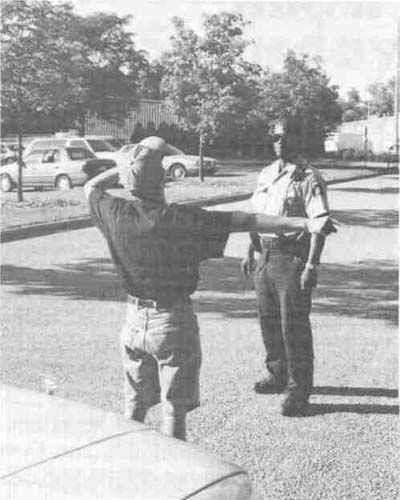

However, the job of Illinois park district law enforcement officers is usually a little quieter than their local non-park district counterparts. But not as much as you may think. Park police agencies are responsible for many law enforcement activities which occur in their jurisdictions. First, let's examine the special events aspect of park law enforcement. Most districts host special events throughout the year, designed to attract people to a given area. They may involve a large number of people for a short time period or smaller numbers for a longer period. Either way, the park district police department is required to provide traffic control and enforcement as well as security, which large amounts of people and personal property always call for. Next, there is routine patrol. The activity level for routine patrol of any given park district law enforcement agency will usually mirror that of the local agency that surrounds most of its park property. Thus, if a park area is surrounded by a high crime area, you can expect some of that high crime attempting to seep onto park property. If this occurs, park police officers will experience some of the same levels of activities as their local counterparts. Parks surrounded by low crime areas usually have a lower level of crime. However, low crime areas can develop some of the most serious criminal activities since most criminals know the police are less likely to be watching or working low crime areas. In addition, if a district has an intergovernmental agreement with one or more of the local police agencies where a district has property, park police officers can find themselves backing up local units on all types of crimes as well as providing solo services when other local units are not available. Park district police officers may also become involved with special units or "details" within the agency. The details are as varied as the agencies themselves. Some may mirror regular law enforcement agencies with positions in administration, training, crime prevention, detectives, or anti-crime. Others may have more of a park law enforcement angle such as a conservation enforcement unit, which looks for poaching violations on park property or various undercover operations.

Conclusion

The Park Police Debate Recently in Illinois and across the country there has been discussion concerning the need for separate park law enforcement agencies. Critics claim they are a duplication of services with existing law enforcement agencies. Advocates claim park law enforcement is a specialized type of law enforcement which, when employed correctly, can greatly enhance the park experience. In this article we examine why, in most cases, park police can make a difference for many park districts. The need and desire to form or maintain a park district police agency always rests with the board of trustees of the park district. The Illinois legislature has given park districts the authority to organize and maintain park district police departments as well as a funding source through a separate park police tax. However, for most small districts a separate park police agency is usually not the most cost-effective means of providing safety and security for park users. If there is a need for additional security above and beyond that provided by the local police agency, a board may consider hiring off-duty officers from the local agency or contracting directly with the local agency for officers. For small districts, this method of providing security is usually less expensive than developing and maintaining a professional park district police agency. This does not preclude a board from electing to maintain a park police agency. Some smaller park districts in Illinois (such as Dolton, Zion, and Morton Grove) have elected to spend the extra money it takes to maintain a professional park district police department to help ensure the safety of their visitors.

Critics claim park police are a duplication of services already provided by

local law enforcement agencies. Yet, this

has not been the experience of many park

districts including three of the larger park

districts in the state (Decatur, Peoria, and

Rockford). They maintain park district

police departments for many reasons, including the public's perception of safety,

managerial control and costs.

Perception of Safety Illinois Parks & Recreation • September/October 1996 • 21 park visit they will be plagued by such problems as loud music, drunks, problem juveniles and panhandlers, they will not use it. However, when a police officer who is not only state certified but is also thoroughly versed in the philosophy of park law enforcement, is put into the same area, case studies indicate the park user immediately feels safer and is not plagued with the problems mentioned above. Why does this happen? Experience indicates that training the officer in the philosophy of park law enforcement plays a definite role, however, the main reason is one of time. Individuals who cause problems in parks know the professional "park law enforcement officer" will always be there. The parks are his or her beat. The officer will not be called away from park district property to handle murders, robberies, batteries, and other crimes which may afflict other areas of the city or county. They will always be there "making our parks a safe place to play."

Managerial Control

However, what happens when there is a serious problem outside of the parks such as a major crime or even a storm that hits the area? Where will these officers be spending their time during such an event? On park property dealing with park problems or inside their respective jurisdictions doing the job they are primarily responsible for doing? Although contracting for police protection is an acceptable practice for some districts, when you consider some of the problems mentioned here, park districts too may find it costs more than an agency is willing to pay.

Costs

Even if the district is getting a good deal from the local agency for small amounts of time, can a local police department absorb this type of request for additional manpower? If so, what is the end cost to the district? If all of these costs are passed on to the district, over the course of three to five years the cost to contract would be the same or higher (depending upon the salary structure) as it would be for developing and maintaining the district's own law enforcement agency. However, with contracting you still do not have managerial control and the increased perception of safety which comes from the district having their own law enforcement agency. In the end, the decision to develop and maintain a park district police department is mainly an economic deci- sion. The costs of developing and maintaining a professional park law enforcement agency is one of the best values in law enforcement today. Harry E. Carlile, Jr., is the president of the Illinois Park Law Enforcement Association (IPLEA) and a sergeant with 15 years experience for the Peoria Park District Police Department. He currently serves on the Park District Risk Management Association's Law Enforcement Advisory Board and the board of directors for the Illinois Police Instructor Trainers Association (IPITA). For more information, contact Sergeant Carlile at 309/686-3359 or the Illinois Association of Park Disricts, 217/523- 4554. 22 • Illinois Parks & Recreation • September/October 1996 |

||||||||||||||