|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

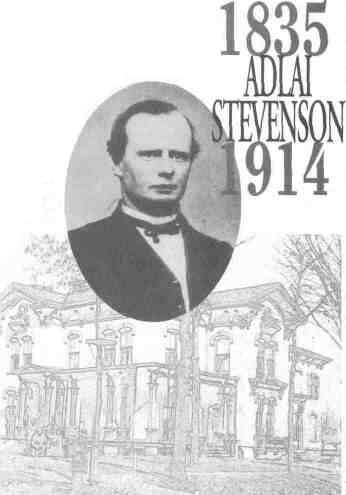

Leonard Schiup, Dynastic political families, an American tradition since the birth of the republic, have often experienced periods of triumph and tragedy. Certainly the Adamses, Harrisons, Tafts, Roosevelts, and Kennedys knew the rewards of victory as well as the sorrows of loss. The Stevensons of Illinois have also contributed to the nation's history. Adlai E. Stevenson I (1835-1914), patriarch of the family and founder of a political dynasty, was vice president of the United States from 1893 to 1897. His son, Lewis G. Stevenson, who served as Illinois secretary of state, unsuccessfully sought the Democratic vice presidential nomination in 1928. The vice president's grandson, Adlai E. Stevenson II, governor of Illinois from 1949 to 1953, was defeated for the presidency in 1952 and 1956, but later eloquently represented the United States as ambassador to the United Nations. His son, Adlai E. Stevenson III, after serving in the Illinois House of Representatives and as state treasurer, won landslide elections to the United States Senate only to retire from politics after two gubernatorial defeats, which brought to a close his family's century of service to the nation. While Adlai E. Stevenson IV has not yet expressed political interests, the recent birth of Adlai E. Stevenson V holds the possibility of a future restoration of the family dynasty. Not one of the descendants of the vice president, however, had as lengthy a political career as his political forefather, the "Sage of Bloomington." The first Adlai E. Stevenson, who attained the highest elective office of any member of his family, experienced both a rewarding and a frustrating career in politics that spanned nearly a half century. He sought political power and enjoyed the pinnacle of his success. A master of political maneuvering unencumbered by rigid ideological restraints, Stevenson was a welter of coexisting contradictions. He could be considerate and calculating, easygoing and ambitious, an achiever and a casualty, and a perplexing mix of private hesitation and political brilliance. Stevenson seemed at times to resemble a political chameleon who assumed the coloration of

11

a particular constituency. His actions often highlighted this perception: the appearance of mediocrity in an obviously intelligent man, trite statements from one who could write well and speak clearly, organizational ability from an incisive politician who vacillated unpredictably, and political activity involving intense partisanship in Washington but nonpartisanship in Illinois. Undoubtedly, part of Stevenson's flexibility was a matter of practicality, for he was a pragmatic politician and coalition Democrat who preached the politics of accommodation. Above all, he was a master of personal relations. In fact, Stevenson's forte as a politician was his closeness to the people. His adoration of the common man and a belief in the American ideal of democracy fortified his political foundation. A prominent Bloomington lawyer, Stevenson entered national politics in 1874 when he secured the nomination of the Democratic party for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. During the campaign, he was personally hurt when his Republican opponent, Representative John McNulta, accused him of having been a Copperhead during the Civil War. The charge of disloyalty to the Union cause offended his sensibilities. Although he had not fought in the war due to family responsibilities, Stevenson assisted in organizing the 108th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry. The local electorate disavowed McNulta's onslaught and Stevenson won the election. The charge, however, haunted him throughout his career. Two years later, Stevenson failed to retain his seat. He succeeded in recapturing it in 1878 only to lose the race again in 1880. Serving in Congress for two nonconsecutive terms and representing a rural Republican constituency, Stevenson in large measure managed to obtain a House seat due to his persuasive skills and political instincts. Persistent salesmanship on his part sustained his image of evenhandedness among his constituents. Yet he won only in off-year contests that coincided with national Democratic victories and majority control of the lower chamber, and he narrowly lost reelection bids in presidential years when he suffered the effects of high voter turnout and presidential coattails. Those defeats tempered Stevenson as a politician and bred a cautious outlook, making him cognizant of his political vulnerability and absence of seniority. A turning point in Stevenson's career occurred in 1884 with the presidential election of Governor Grover Cleveland, a New

12

York Democrat. Stevenson became first assistant postmaster general in the new administration. While functioning in this role, he removed nearly forty thousand Republican postal employees across the nation, replacing them with Democrats. Stevenson relished this assignment, for he typified the spoilsman of the 1880s who earned the wrath of civil service reformers, whose criticisms he accepted as compliments. These duties and responsibilities gave him a new sense of purpose and whetted his appetite for higher office. He had become infatuated with Washington life. After Cleveland's defeat for re-election in 1888, he selected Stevenson for an associate justiceship on the Supreme Court for the District of Columbia, but revengeful Republicans, who controlled the Senate, blocked the nomination. This judicial defeat wounded Stevenson personally but failed to end his political career. Chairman of the Illinois delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1892, Stevenson surfaced as the vice presidential candidate. His nomination, a political development based on the demands of practical politics, stemmed from several factors, including his ability to mollify discordant elements within the party. A political moderate and gentleman of temperate disposition with unquestioned personal integrity, Stevenson did not antagonize diverse intraparty groups, and he found himself in the advantageous position of being a compromise choice. He emerged as the Great Conciliator, providing both philosophical and geographical balance to the ticket headed by Cleveland. Stevenson conducted a whirlwind campaign that fall, visiting several states. When Democrats won the presidential election, William F. Harrity, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, credited Stevenson with having contributed to the victory. The vice president's political future looked bright indeed on inauguration day, March 4,1893. In the next four years, Stevenson's life turned from triumph to tragedy. He suffered a personal loss in the death of a daughter and the political humiliation of losing the presidential nomination in 1896. The vice president endured the frustrations and unrewarding tedium that were inseparable from his office and confronted unexpected developments that damaged his political credibility during Cleveland's problem-plagued presidency. The Panic of 1893 and ensuing severe depression gave rise to political protest, economic distress, and social unrest. Moreover, Stevenson was caught in the middle in 1894 when Cleveland dispatched federal troops to Chicago to quell the Pullman Strike, an action called by the American Railway Union that immobilized railroads in the Midwest. The president's decision met with hostile opposition from Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld, who angrily condemned Cleveland. Not wishing to antagonize either Cleveland or Altgeld, Stevenson remained reticent on the issue. These national problems, together with the vexatious currency question, spawned crippling divisions within the Democratic party. As a result, in 1897, instead of moving into the White House, Stevenson barely escaped political extinction. The most trying time politically for Stevenson occurred in 1896 when the contentious money issue strained his relationship with "sound money" and "free-silver friends" in the party. Agitation for resuming silver coinage increased when new discoveries of silver were made in the West. The expansion of silver production coincided with an international trend toward adoption of the gold standard. Advocates of gold feared that the free and unlimited coinage of silver would drive gold from circulation and contribute to inflation. Silverites, on

13

Adlai E. Stevenson Home

Also that year the vice president experienced internal conflict—a match between the gentleman in his Prince Albert coat and the politician who wore many hats. The enigma was how far Stevenson could perpetuate his political ambitions without antagonizing the Cleveland conservatives. Stevenson's instinct told him to keep his two jobs—vice president and practicing politician—distinct, but that was a self-defeating mistake that undermined his chance for the presidency. He not only misjudged the political situation that year, but everything he did seemed desperate and insincere. In short, Stevenson's style of leadership was his strength and, in the end, his undoing. Radical silverities, who espoused the free and unlimited coinage of silver at a ratio of sixteen to one with gold, viewed Stevenson as an unlikely patron of change. Secluded in his Bloomington home at the time of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Stevenson experienced a rapid fall from grace. Stevenson's innate political cautiousness, a successful trait in the past, proved calamitous in the tumultuous arena of Democratic politics in 1896. It was the ultimate irony for someone who had achieved success in the political world with his talent for fashioning compromise and shunning confrontations. Preferring to merge groups into the middle ground of happy consensus, the vice president, torn between fiscal orthodoxy and the free-silver crusade and holding to the Jeffersonian model of executive leadership, ultimately had to displease one group or the other by stating what kind of monetary system he envisioned for the nation. Stevenson was caught between the vacuum that was former President Cleveland and the resentment that was William Jennings Bryan, a rising young Democrat. Stevenson, whose interest was in the larger aspects of governing, faced his worst political identity crisis in 1896, bedeviled by an issue he sought to avoid. He tried to appease all factions with concessions but went down to humiliating defeat when nontraditional conditions between reformers and regulars demanded a different approach. Stevenson's longed-for presidential ascendancy in 1896 would have required deep intraparty wrangling fueled by a policy clash with insurrectionists over the money issue, a deadlocked convention, and his emergence as a compromise savior on a platform of prudence and moderation. It did not happen. Vice President Stevenson, who found value in both sides of the currency argument, lacked the personal dynamism 14 to energize Democrats with frenzied enthusiasm; he was not the heroic figure that the occasion demanded that year. He created an impression of indecision or unpredictability that undercut what he had attempted to convey earlier—namely, that his fidelity was to the Democratic party and that he would remain its faithful servant. Stevenson believed that a major portion of his task was to gauge accurately the limits of the politically possible and then to remain within those boundaries. In the end, the courtly vice president became an unwilling victim of his own political practice. In many ways, Stevenson was a typical product of nineteenth-century American politics. Following the Civil War and prior to 1896, real issues were often buried under the bombastic recollections of the civil conflict. Compromise and even vacillation were necessary for political success, and Stevenson was quite successful with both. On the other hand, highly divisive issues such as slavery, which confounded Henry Clay, and the money question, which tormented Stevenson, defied compromise, and the skilled neutralists were shunted aside. This perhaps more than anything else explains Stevenson's political demise in 1896. It was a portrait of a master politician skillfully moving through a series of successes that made his ultimate failure all the more tragic. After Bryan's defeat for the presidency in 1896 and the end of Stevenson's term as vice president in 1897, Stevenson returned to his law practice in Bloomington and to the presidency of the McLean County Coal Company. He surfaced again politically in three years. When events took a surprising turn in 1900, delegates to the Democratic National Convention in Kansas City extricated Stevenson from political retirement by choosing him for vice president to run with Bryan. He received the vice presidential nomination on the first ballot in 1900 because he was the most available man to provide the stability and harmony that the party needed that year. Nominated in 1892 as a liberal to balance a state led by a conservative, the rehabilitated Stevenson obtained a second nomination in 1900 as an elder conservative statesman to balance a ticket headed by a progressive. The Democrats changed presidential nominees and philosophical direction in eight years but kept Stevenson. The vice president's talents to survive politically in both the

15

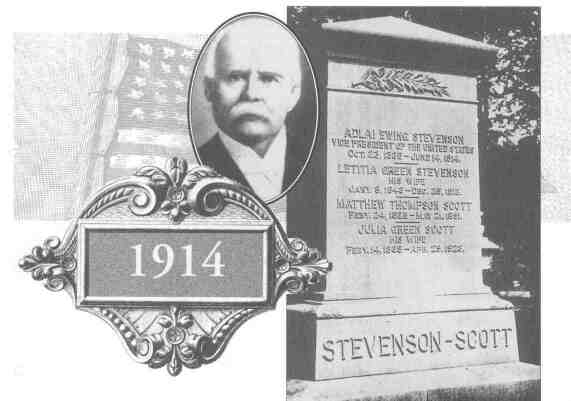

Cleveland and Bryan camps in the same decade earned him the distinction of being the American Talleyrand of the era. (Charles Maurice Talleyrand-Pengord, 1754-1838, was a French diplomat and statesman noted for his wily negotiations.) Stevenson traveled the nation during the fall campaign, enunciating his opposition to trusts and imperialism. Following Bryan's defeat in 1900 at the hands of President William McKinley Stevenson returned to Bloomington. There he lived a quiet life as a respected elder party spokesman. In 1908 he narrowly lost the Illinois gubernatorial election. Vote fraud in Chicago wards controlled by Republican Mayor Fred A. Busse probably cost Stevenson the governor's office. Six years later, Stevenson died in a Chicago hospital. Possessing both strengths and weaknesses, Stevenson must be analyzed within the complicated political context in which he lived and the ambiguities of his beliefs and policies, for he embodied the contradictions of an age that was simultaneously resisting and welcoming the ongoing change of society Like most Gilded Age politicians, Stevenson suffered from an inability to recognize that the major problem of his generation reverberated around the adjustment of American politics to the enormous economic and social transformations imposed on the United States by industrialization and urbanization. Part liberal-progressive and part conservative-moralist, both a reformer and a conformer, Stevenson, controlled by the political and economic forces in his age, sought the society of Old Guard security but often registered dissenting opinions. Although not in the first rank of great men of his generation, Stevenson was a good vice president in an era when the public neither expected nor sought great political leaders. He also served as a transitional figure in bridging the passing of the Democratic party from the conservatism of Grover Cleveland to the progressivism of Woodrow Wilson. Like many nineteenth-century vice presidents, however, Stevenson failed in his quest for lasting fame. His glory, like that of many who preceded him, rested in achieving, rather than holding, political office. On the other hand, as the founder of a political dynasty, Stevenson's contribution to the American political tradition was a legacy for his family and the nation.

Click Here for Curriculum Materials 16 |

|

|