|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

CIVILIANS,

Theodore J. Karamanski Soldiers from Illinois clashed with southern rebels at Athens, Alabama, in May 1862, and sacked the town. Yet, the name of Athens does not appear on the list of battlefields associated with the Nineteenth and Twenty-fourth Illinois Infantry. What happened in Athens was an atrocity, by no means on the scale of My Lai or Lidice, but an arresting break with the image of Christian soldiering that had marked the initial year of the American Civil War and a step on the road toward making the conflict a total war. The incident at Athens is an example of how in the course of a war both politics and society become enmeshed in the escalating violence of the conflict. The incident occurred in the wake of the costly Union victory at Shiloh. The federal Army of the Ohio pushed deep into the Confederacy after capturing and using the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The sudden occupation of northern Alabama shocked Southern civilians. Among the many towns garrisoned by the Yankees was Athens, the seat of Limestone County and home to nine hundred civilians. Many of the townspeople professed to being pro-union and offered to cooperate with the Army of the Ohio. That may have lulled the soldiers into a false sense of security because on the morning of May 1,1862, the First Louisiana Cavalry mounted a surprise attack on the garrison, driving the Union soldiers from the town. Residents of Athens delighted in the blue coats' rout, aiming curses and spit at the fleeing foe. The rebel cavalry was "greeted with cheers and a waving of hats and handkerchiefs... the ladies at the tavern brought to light a Confederate flag that hasn't seen the light in some time...," wrote diarist Mary Fielding. As many as one hundred townsmen joined with the Confederate soldiers in a six-mile pursuit of the retreating federal garrison. Rebel commander Colonel J. S. Scott reported, "My boys took few prisoners, their shots proving singularly fatal." The fortunes of war swung just as suddenly the next day when the Eighth Brigade (consisting of the Eighteenth Ohio, Thirty-seventh Indiana, Nineteenth Illinois, and Twenty-fourth Illinois) forced the Confederates to once again abandon Athens. Colonel John Basil Turchin led the counterattack. Determined to punish the citizens of the town for what he regarded as treacherous conduct, Turchin strode into the town square and loudly told his officers and men: "I shut my eyes for two hours." The angry and tired soldiers required no further clarification, and they proceeded to sack the town. Shop windows were shattered, and in short order jewelry stores, druggists, and dry goods stores were relieved of their wares. With enthusiasm the troops then turned to the private homes of Athens. Bureau drawers were pulled to the floor and trunks were pried open with bayonets and rifled in the quest for valuables. Some men feverishly pocketed silver utensils, gold watches, and jewelry. Others simply sought the tobacco, sugar, or molasses that would improve their rations. Most— even officers— seemed to have delighted in insulting the men and women of the town. Although physical violence was kept to a minimum, troops firing their guns into one home unknowingly caused a pregnant women to suffer a miscarriage, resulting in both the mother's and fetus's death. "Indecent and beastly propositions" were made to many of the women, and at least one "servant girl" was raped. When night came, the soldiers appropriated private homes and completed their despoilment by chopping roasts on pianos and cutting bacon on rugs before retiring. "Men who had been sleeping in the 48 mud," one veteran recalled, "laid fine broadcloth on the ground that night and slept on it."

The sack of Athens, Alabama, seems mild in light of the recent civil war in the former Yugoslavia, yet, in the summer of 1862, the action was deeply shocking to American soldiers and civilians. What happened on May 2 was an atrocity to Americans because both North and South had gone to war with an idealized vision of war and the warrior. Victorian commitment to duty, knightliness, bravery, manliness, and most of all, honor placed a heavy burden of expectation on the volunteer soldier. Men were expected to bring to military service a perhaps unrealistic combination of aggression and forbearance. The Chicago Zouave Cadets, Illinois' leading pre-war militia company, reflected those values when it required each of its men to swear not to enter a saloon, brothel, or billiard parlor. At the outbreak of the war the Zouaves helped form the Nineteenth Illinois Infantry, the very unit that ravaged Athens. Even within the Union Army, the reaction to Colonel Turchin's actions at Athens was swift and negative. Area commander General Ormsby Mitchel hurried to the town immediately upon hearing of the incident, met with the victimized citizens, and encouraged them to establish a committee to gather complaints against individual soldiers. While Mitchel promised to punish those responsible, "if the perpetrators could be found," he was sympathetic to the frustration created in his men by rebel hit-and-run tactics. Without sympathy for Turchin and his men was Major General Don Carlos Buell, who labeled the incident an "undisputed atrocity" and ordered a court-martial to examine charges against Turchin and his officers. Brigadier General and future U.S. president James A. Garfield, who was ordered to preside over the trial, initially believed that Turchin's men had "committed the most shameful outrages on the country here that the history of this war has seen." John Basil Turchin sat before the court-martial for ten days while the citizens of Athens enumerated the abuse they suffered at the hands of his Eighth Brigade. Turchin made an appealing villain. He was born Ivan Turchinenoff and was educated in a Russian military academy. After rising to a post on the Czar's staff during the Crimean War, Turchin immigrated to the United States. He settled in Chicago, where he was one of the leading construction engineers for the Illinois Central Railroad. Testimony by the Alabamians, however, painted Turchin "as fierce and brutal a Muscovite as the dominions of the Czar could produce." Such descriptions reveal native-born Americans' suspicion of immigrant soldiers as potentially more brutal and less honorable than native-born Americans. This suspicion was reenforced by the fact that the Twenty-fourth Illinois, which participated in the sack of Athens, was a largely German unit. Its Colonel, Geza Mihalotzy, also a veteran of European armies, was reprimanded for having "behaved rudely and coarsely to the ladies" of Athens.

49

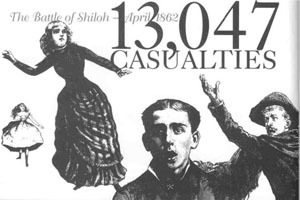

But Colonel Turchin had no intention of quietly subjecting himself to General Buell's discipline. In the weeks after Athens, Turchin openly disobeyed Buell's orders to protect all private property, by ordering his men to burn the nearest farm house whenever they were fired on from ambush. In his defense before the court he refused to refute the bulk of the charges against him. "I have tried to teach rebels that treachery to the Union was a terrible crime," he said. "My superior officers do not agree with my plans. They want the rebellion treated tenderly and gently. They may cashier me, but I shall appeal to the American people and implore them to wage this war in such a manner as will make humanity better for it." Even while the court-martial deliberated, Turchin's words began to resonate in the court of northern public opinion. The press lionized Turchin as a "man who handled our enemies roughly." James Garfield, the head of the court-martial, received a letter from his wife that reflected the public's view of the proceeding. "I hope you will find Col. Turchin guilty of nothing unpardonable," she wrote,"... severity and sternness should be turned to the punishment of rebels for the barbarities committed on our boys rather than to the punishment of our own... It seems very strange that as soon as a man begins to accomplish something in the way of putting down the rebellion he is recalled, or superseded, or disgraced in some way." For a brief time in the summer of 1862 Turchin became a symbol of a fundamental change in public opinion among midwesterners. The war goal of 1861 had been to restore the southern states to the Union, slavery and all. The rebellion was seen as the action of a hot-headed minority of southerners. It took a year of fighting to convince most Illinoisans that the Confederacy had deep support and that defeating the South would entail a desperate struggle. Shiloh, fought in April 1862, drove home that point. Of the sixty-five Union regiments engaged in the battle, twenty-eight came from Illinois; the 13,047 casualties suffered in the victory were a terrible shock to the Prairie State, and polarized public opinion. A sizable minority turned against the war in disgust and formed the basis for a strong peace movement. To bolster support for the war, Republican newspapers, the Chicago Tribune among them, began to demonize the rebels with rumors of atrocities against northern soldiers. The brutal slave system had made southerners full of "the malignant fury and the foul lust of the savage," and therefore different from other Americans.

50

Even after he was found guilty by the court-martial, Turchin remained a potent symbol of a new willingness on the part of Illinoisans to see the harsh hand of war directed against the citizens of the South. Although General Buell ordered Turchin dismissed from the Army, Turchin was invited back to Chicago, his adopted hometown, for a hero's triumph. Amid the "din of clapping hands, stamping feet, vivas and huzzas," Turchin announced that instead of being sacked from the service, President Abraham Lincoln had set aside the verdict of the court and promoted him to the rank of Brigadier General. Before a hall packed with over-heated Republicans, politicians proclaimed that Turchin's promotion was a sign that "this kid glove business is all played out." Turchin himself called for enlisting slaves against their masters and closed his address by saying: "What I have done is not much; but what I could do, were I allowed might amount to something... We have been talking about the Union and hurrahing the Union a great while. Let us now talk and hurrah for conquest." Turchin returned to duty and proved himself an able brigade commander in the battles of Stone River, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga before retiring due to wounds in 1864. General Don Carlos Buell, disdained by many Republicans as harboring "proslavery" sentiments because of his determination to protect southerner's property, was himself relieved of command in October 1862. Buell's unaggressive pursuit of the rebel army after the Battle of Perryville and his attempt to scuttle Turchin eroded Lincoln's confidence in Buell's judgment. Athens, Alabama, was occupied several more times during the course of the war. Although the courthouse was burned during one occupation, the blaze appears to have been an accident. The Union army refused to pay a penny of the $54,689 claimed by the victims of Turchin's visit. The sack of Athens was a minor event in the course of the Civil War. Yet, what happened in that north Alabama town and Illinois' reaction to it brings into sharper relief the escalation of the Civil War. Whether the Civil War was ever a total war—one in which civilians as well as the soldiers of the opposing side were the declared enemy—is open to interpretation. But beginning with Athens, Illinoisans accepted the necessity of making the southern people pay the price for rebellion in destroyed property. From that acceptance came the political will for the Emancipation Proclamation and the infamous March to the Sea. As one Chicago veteran of the Athens incident later recalled, "It was pitiful, but it was war." Click Here for Curriculum Materials

51

|

|

|