JOHN WHO?

Democrat John Schmidt wants to be governor, but don't worry if you've never heard of him. He can afford the kind of campaign that makes someone a household name in a hurry by Mark Brown Photographs by Jon Randolph John R. Schmidt, the man Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley would prefer as the next governor of Illinois, was marching this spring in a St. Patrick's Day parade through the city's Beverly neighborhood when he chatted up a fellow about the need to replace Jim Edgar. "You're right," the gentleman eventually agreed. "We do need a new governor. What's your name again?" If you can't place the name, let alone the face, don't worry. Even in the Democratic strongholds of his hometown of Chicago, most people couldn't pick John Schmidt out of a police lineup filled with other lawyers suspected of yearning for elective office. But be assured, one year and millions of dollars in television commercials from now, all that will have changed. Schmidt, who tells the parade story on himself, can afford to poke fun at his anonymity. With a personal net worth in excess of $7.5 million and friendships with most of Illinois' major Democratic donors, he also knows he can afford the kind of campaign that makes someone a household name in a hurry. And while spending a lot of money doesn't guarantee anything in politics, it helps. Schmidt, 53, will use the money (he says he expects to spend relatively little of his own) to sell himself to Illinois voters as a thoughtful reformer with a record of getting things done in Chicago, Springfield and Washington, D.C. Those commercials will undoubtedly stress his role in putting more cops on the nation's streets as the third-ranking official in the U.S. Justice Department, as well as the jobs and tourism dollars resulting from his chairmanship of the agency that renovated Chicago's Navy Pier and expanded the city's McCormick Place convention center. Rounding out the picture may be reminders of his past crusades to reform the Cook County courts and the state's mental health laws. If he can survive the countervailing spin that he's just another rich lawyer who is too liberal, untested and beholden to Chicago's mayor, Schmidt might still be around next summer to make good on his promise to go on the attack against Edgar, or whomever the Republicans nominate, for what Schmidt likes to call the "drift and decline" of state government during [the GOP's] 22-year death grip on the governorship. "Fundamentally, I see myself as running on a record of having held major public office and shown I can achieve important results," says Schmidt, who doesn't think voters will mind that none of those offices have been of the elective variety. "I think people like the idea of someone who is not a career politician whose objective has simply been to get elected to one office after the other." His friends see John Schmidt as the smartest guy in the room, yet nice enough to let you figure that out on your own, a principled public servant who has never used his government service for personal financial gain. "Intellectually, he has few equals," says Chicago journalist/political consultant Rob Warden. Schmidt's doubters, though, wonder about his evolution from reformer to insider, from someone who made his mark in Chicago as an antagonist of the late-Mayor Richard J. Daley to someone who draws at least part of his political viability from the expectation that his good friend, Daley's son, will support him in the Democratic primary. Both friends and doubters wonder aloud whether his reserved, cerebral style will allow him to connect with the public. So far, he's been better at achieving that in small group settings than large political events, where he still seems too boring and a little out of place. Patrick Botterman, Democratic committeeman of Wheeling Township in Chicago's northwest suburbs, says 30 of his party activists sat in for a 105minute get-acquainted session with Schmidt this spring and 90 percent of them signed up afterward to volunteer in his campaign. "I think Schmidt is the type of candidate that many suburbanites could embrace," Botterman says. "He didn't walk in with all the answers. He wasn't political to the point that you could see your own Illinois Issues June 1997 / 23

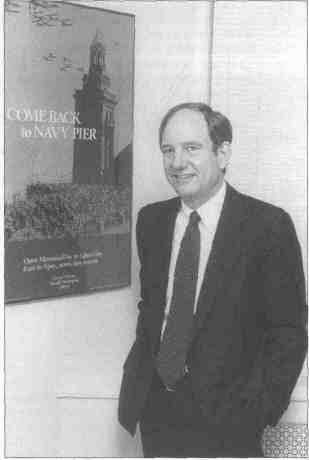

reflection in his face." Still, a statewide campaign is bound to be a tough haul for someone who hasn't stood before the voters since getting elected secretary of his seventh grade class. "I don't think there's any question that he would make a superb governor," says former U.S. Sen. Paul Simon, who benefited from Schmidt's fund-raising efforts during his 1988 campaign for president. "What he has to prove to people now is that he will be a good candidate." Former state Comptroller Dawn dark Netsch, the Democrats' failed 1994 gubernatorial nominee, agrees. "He may be a better governor than he is a candidate. That was Adiai's problem," she says, comparing Schmidt to former U.S. Sen. Adiai Stevenson III, her party's losing nominee in 1982 and 1986. Contemplating Schmidt on the campaign trail, she observes, "I don't think it's his natural milieu." It's an odd situation for someone who has always been regarded as an effective public speaker, dating back to when he helped his Evanston Township High School debate team win the state championship. But Schmidt has quickly found that political communication poses its own unique challenges, which he is determined to master. Unlike other wealthy Chicago lawyers of recent history who got a hankering for elective office and wanted to start at the top, Schmidt lacks the charisma that goes with a successful courtroom practice. As a corporate lawyer who specialized in merger and acquisition work, he has never tried cases. He's the kind of lawyer you might send in on occasion to face the Supreme Court, but not a jury. Colleagues say he's at his best running a meeting or conducting negotiations. Schmidt, though, has something the other lawyer-candidates didn't have: a long history of involvement in public affairs. Here are the highlights: • At the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach, Schmidt and law partner Wayne Whalen humiliated the senior Mayor Daley by engineering the credentials challenge that ousted his delegation and replaced it with a group led by then-Chicago Aid. Bill Singer and the Rev. Jesse Jackson. • As a founder and president of the Chicago Council of Lawyers and the primary financial benefactor of Warden's Chicago Lawyer magazine, Schmidt crusaded throughout the 1970s and 1980s to reform the Illinois courts, beginning with reducing the control the senior Daley's Democratic organization exercised over the Cook County judiciary. The council, an anti-establishment bar group, helped head off two of the senior Daley's picks for the state Supreme Court and campaigned successfully for the ouster of Cook County Chief Judge John S. Boyle. • Gov. Dan Walker picked Schmidt in 1973 to serve on a 25-member commission that studied and then proposed broad revisions in Illinois' mental health laws. Schmidt was later 24 / June 1997 Illinois Issues given responsibility for working with the legislature to turn the recommendations into law. It was a role that brought him into close contact with the current Mayor Daley, then a lightly regarded state senator who had decided to make his first mark as a serious politician through mental health reform legislation. A few years later, Gov. James R. Thompson appointed Schmidt the first chairman of the Illinois Guardianship and Advocacy Commission, which provides legal assistance to those with mental and physical handicaps. • Having forged a friendship during their work on the mental health legislation, Schmidt enlisted in Daley's successful 1980 campaign for Cook County state's attorney and headed his transition team. He supported Daley in the 1983 Democratic mayoral primary over eventual-winner Harold Washington. When Daley ran again in 1989. Schmidt was first in line with a $150,000 loan to his campaign. a crucial assist in that Daley had just exhausted his funds in a state's attorney reelection bid. Again Daley called on Schmidt to run his transition team, then kept him on four months as his unpaid chief of staff while Daley got his feet on the ground. • Daley then made Schmidt chairman of the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, where he helped cut the $1 billion deal to finance McCormick Place expansion and developed the concept for the Navy Pier renovation that has proven extremely popular.

As extensive as it is, Schmidt's resume is notable as much for what it lacks: any post in which he had to compile a voting record. "I'm envious," says Netsch, who was bludgeoned with her own legislative record in 1994. "There's nothing they can go after him on." Yet some Chicago Democrats who are less than enthusiastic about Schmidt's candidacy have taken to referring to him as John dark Schmidt or Dawn dark Schmidt, meant as an unflattering comparison. Netsch and Schmidt are indeed kindred political spirits. They come out of the same Lakefront independent wing of the Cook County Democratic Party and have worked together over the years for merit selection of judges. These days they work just down the hall from each other at Northwestern University's Law School, where Netsch is a professor emeritus and Illinois Issues June 1997 / 25 Schmidt is teaching a constitutional litigation seminar. Schmidt's Justice Department post kept him on the sidelines during Netsch's 1994 campaign for governor, but his wife, Janet Gilboy, donated $25,000 to her cause. And Schmidt seems to share Netsch's sense of vindication that Edgar has embraced the concept for which he savaged her in the 1994 campaign: an education funding plan that would swap higher income taxes for lower property taxes. When he was interviewed in April, Schmidt said he hoped the education funding debate in the legislature would be resolved with a plan to increase the income tax and the tax on riverboat gambling profits while reducing property taxes. The state, he said, should provide at least 50 percent of the funding for education. (He's even picked up the old refrain about the Illinois Lottery being a "shell game" that doesn't really increase the amount of money going into education.) At the same time, Schmidt said he opposes any attempt to limit what wealthier school districts can spend on educating their students. "I believe strongly that the last thing we want to do is level down. ... I've never thought the problem was inequality as such," Schmidt said. "The problem is that we don't have a system where every school has the basic resources it needs to provide a decent education." Early in his campaign, Schmidt has ripped the Edgar Administration for the influence of street gangs in the state prison system. He touts community policing as "the single most important factor in bringing crime rates down." And he doesn't seem interested in handwringing about the explosion in prison construction. "I think, in general, the fact that we've sent serious offenders away for longer periods of time is positive," Schmidt says. "We need to build whatever jails or prisons are needed in order to carry out appropriate sentences." He supports the death penalty and cites as one of his federal accomplishments an effort to limit the appeals process for someone awaiting execution Among his other positions: • He supports the ban on assault weapons. • He is critical of the state's record on collecting child support payments. • He is pro-choice and points out that it was part of his responsibility at Justice to make sure women have safe access to abortion clinics. "I believe I can win because I believe I stand with the majority of Illinois citizens on the critical issues," Schmidt says, in a not-so-subtle dig at Democratic U.S. Rep. Glenn Poshard of Marion, the first announced gubernatorial candidate, for his positions against abortion and gun control. Poshard, meanwhile, is clearly irritated at having to compare his credentials with someone who has never been in elected office. "I don't think Mr. Schmidt has ever cast a vote in his life," Poshard responds. "When you've been in the arena, you take some lumps. You get some people mad at you. I've been in the arena." With the help of U.S. Rep. William Lipinski, Poshard has been campaigning hard in the Chicago area in an effort to make inroads before Schmidt or anyone else can establish himself, possibly forestalling the day when Daley weighs in. As yet, Daley hasn't endorsed Schmidt, for his own purposes and for Schmidt's. The mayor rarely gets involved early in somebody else's election, preferring to let things shake out on their own. But there is no doubt that he's for Schmidt if Schmidt is still standing next spring. Many of Daley's political advisers, including former state Sen. Timothy Degnan and media consultant David Axelrod, are already assisting the Schmidt team. In fact, Schmidt seems to want to distance himself from Daley for a while, to prove he's an independent presence. As evidence, he cites a handful of Chicago political contests in which he and Daley chose different sides, not policy differences. "I've never had a situation where there's the slightest suggestion he would tell me what to do on anything." Make no mistake, however, Daley's guy or not, Schmidt enters this campaign with a decidedly Chicago point of view. On the question of the expansion of gambling, for instance, he supports bringing riverboats to Cook County, but isn't interested in any other forms of gambling. "I have always thought that Cook County ought to be able to do whatever can be done elsewhere in the state." He continues to defend a proposal he tried to advance while at the McPier Authority that included a statewide hotel-motel tax as part of a package to finance the McCormick Place expansion and a new domed stadium for the Chicago Bears. Downstate legislators helped kill that plan. Schmidt is definitely someone who loves the city. He and Gilboy live with their 13-year-old daughter, Laura, and a scampish West Highland White Terrier named Brittainy in a $1.5 million condo in the exclusive Lakefront neighborhood that Chicagoans call the Gold Coast. Gilboy, a sociologist by training, is a researcher at the American Bar Foundation. Laura is a student at the pricey private Latin School. But the Christmas wreath still hanging in late April on the living room wall provides evidence that Schmidt's attention is elsewhere these days. Schmidt was raised in Evanston, the second oldest of four sons born to Edward and Josephine Schmidt. Edward was a top executive of W.W Grainger Inc., eventually becoming president of the company that he helped grow into one of the country's largest distributors of electrical parts. Josephine, the daughter of an Indiana state legislator, was the only Democrat on the block in what her son recalls was then a staunchly Republican Evanston. The home, four blocks in from Lake Michigan, was very comfortable, but certainly not what some would associate with a modern CEO. Edward didn't actually get the top job until Schmidt was seven years out of high school. Schmidt took no part in student government at Evanston Township High School, where he played the trombone and piano and studied hard, graduating fifth in a class 26 / June 1997 Illinois Issues of about 1,000 in 1960. "Music has been something that's been very important in our lives," says Robert Schmidt, the candidate's brother and campaign treasurer. Edward and his sons performed around town in their own brass quartet. During the four years of commuting back and forth from Washington on weekends, Schmidt would often fly to Chicago on weekday evenings to attend his daughter's flute recitals and then fly back the next morning in time for an early meeting, Robert says. Schmidt sticks to the piano these days, mostly accompanying Laura on the flute, although he has also been known to entertain friends with show tunes. A lover of the symphony, he's also been known to throw a party by commissioning an original composition by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Ellen Zwillich, have the Chicago Symphony Orchestra perform it and then arrange for conductor Sir Georg Soiti to come out afterward to greet his guests. Ameritech General Counsel Kelly Welsh, Daley's first corporation counsel and Schmidt's replacement at the McPier Authority, regularly attends the opera with the Schmidts but hastens to add that his old friend is just as comfortable at a ball game. Schmidt got his law degree from Harvard, graduating cum laude in 1967. His draft status during the Vietnam War was 4-F because of asthma. He met Gilboy on a blind date after returning home to join the law firm of Mayer, Brown & Platt. They immediately agreed to collaborate on a scholarly paper, "'Voluntary' Hospitalization of the Mentally 111," that was published in the Northwestern Law Review in 1971. It took them 12 more years to get married. He still says she is his best friend. His net worth comes from inheritance and his law practice. Indeed, the money really started rolling in when he and Whalen split from Mayer, Brown & Platt to open a Chicago office for Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, a New York firm that made its mark as the go-to guys in the go-go 1980s era of corporate raiders and hostile takeovers. In those high-flying days, Skadden partners were reportedly making a million dollars a year. Schmidt's 1993 buyout from the firm earned him $2.5 million. Some think the law practice is Schmidt's Achilles' heel in a campaign, but aside from his role in the merger of Centel Corp. and Sprint, in which the Chicago area lost 500 jobs, there isn't much evidence that Schmidt was involved in deals that led to a lot of downsizing. It could even be argued the Centel merger was better for the company's workers than the alternatives. Schmidt says he was usually on the defensive end in takeover battles. Likewise, there is no evidence that he used his Daley ties to cash in with legal business from the city or any other public agency. Schmidt only brought one lobbying client to City Hall after he left, according to public disclosure forms. And Securities Data Co. reports Skadden showed up on only one city bond deal after his departure. "I don't think there's any nexus between his private practice and his public involvement," Whalen says. So what does motivate a guy to give up a highly lucrative law practice to run for public office?

Usually, of course, it's ambition, and there is little doubt that Schmidt has been bitten by that bug. But his friends swear there's something else. "I really believe he's doing it because he thinks he owes something back," says Gary Nickele, general counsel for JMB Realty Corp., one of Schmidt's former clients. A contributing factor may have been the 1993 death of his younger brother Willard. age 47, from a brain tumor. "It's the kind of thing that, when it happens, you say to yourself, 'I should do the things I believe in, and I shouldn't wait.' It gives you a sense of the fragility of life and of the importance of your own values," Schmidt says. As much as anything, Schmidt seems to think he's the right guy for the job. "I always thought if there was an elective job that I would be good at, it would be governor," he says. "I do think that I have an executive temperament. I think I'm good at setting objectives and moving toward them and bringing people together to move toward them. That is a lot of what a governor does." Mark Brown is a reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times. Illinois Issues June 1997 / 27

| |||||||||||||||||||