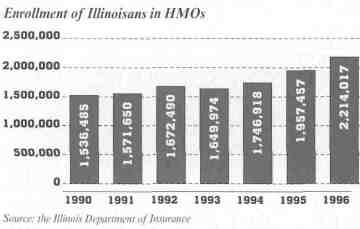

CRITICAL CONDITIONManaged care reforms have been put on life support, but the long-term prognosis is uncertain by Frank Vinluan Jerry Prete winces in pain these days, it's only because he remembers how managed care handled his back problem. Two years ago, the 77-year-old Chicago resident sought treatment for spinal stenosis: pressure on. the spinal nerve from bone growth in the vertebrae. Such activities as kneeling, walking, even sitting, caused anguish. Despite Prete's request for a neurosurgeon, his primary care manager — who was not a doctor — advised against surgery and instead referred him to his regular doctor. Prete's health maintenance organization had no neurosurgeon in its network. Only at his insistence did his HMO finally refer him to an orthopedic surgeon, though it would not disclose information on the surgeon's experience treating spinal stenosis. "I was at the end of my rope. I was in constant pain," he says. Frustrated with the process, Prete dropped out of his HMO and used Medicare. Staying with his HMO, he says, would have meant eventual confinement to a wheelchair. Managed care, often through HMOs, was originally conceived as a way of improving access to health care while controlling costs. But Prete's story highlights a situation critics say is increasingly common with managed care plans: difficulty in getting to specialists for necessary treatment. They argue such problems point to the need for reform. Yet the insurance industry dismisses "anecdotal stories" as exceptions, not the rule. And businesses worry reform will translate into added costs through mandated procedures. The Illinois Senate wants to hear all sides in greater detail. Sen. Tom Walsh, chair of the Senate subcommittee on managed care, began taking testimony in April. The LaGrange Park Republican says more public hearings will be held this summer. "We plan on looking at everything and trying to come up with a workable solution," he says. This spring, possible solutions were outlined in more than 30 health care and health care coverage bills. Some measures dealt with more comprehensive reform, while others addressed specific coverage, such as emergency care or hospital stays following a mastectomy. Of three House measures proposing comprehensive reform, only one made it to the Senate. It was held in Walsh's committee. That "consumer protection" bill would address cases like Jerry Prete's by granting specialist referrals to treat specific conditions. Rep. Mary Flowers, a Chicago Democrat, sponsored the measure. "We heard horror stories in my district, all across the state, all across the country," she says. "It's unfortunate that's the reason why we're doing what we're doing." The proposal includes provisions that clarify the terms of a patient's coverage — a key factor in winning the support of health care reformers. Whereas consumers can find out about goods or services from business groups, no such resource exists for health care organizations, according to Jim Duffett, director of the Illinois- based Campaign for Better Health Care. "Right now, I can learn more about my refrigerator than my own HMO." The Senate's cautious approach is understandable given the issue's complexity. In recent years, HMOs have flourished nationwide, and the number of people enrolled in such health plans has increased. Illinois has 47 licensed HMOs, enrolling roughly 2.2 million of the more than 10 million Illinoisans covered by some type of public or private health insurance. Managed care, as the name suggests, means controlled medical access. Rather than provide fee-for-service care, primary care doctors serve as "gatekeepers." In theory, by emphasizing preventive medicine and directing patients toward the appropriate treatment, managed care provides quality care while keeping costs down. Cost, counter critics, is HMOs' top priority. "The cheap and easy way to save money is to keep enrollees from getting health care," says Bettina French of the Illinois Hospital and HealthSystem Association. But the HMO industry argues that cost control and quality care are synonymous under managed care. Robert 28 / June 1997 Illinois Issues Burger, executive director of the Illinois Association of HMOs, says the problems people associate with managed care are not different from problems found in other types of health care. The advantage is the system managed care provides for identifying and redressing patient complaints. And, Burger maintains, those complaints are few and far between. Of Illinois' 10 largest HMOs, only American Health Care Providers of Matteson averaged more than five complaints per 10,000 enrollees in 1996. Although managed care through HMOs has long been a health care option, it was with President Bill Clinton's unsuccessful 1993 initiative for a national health care policy that it became a contentious issue. Clinton tried to find a way to broaden health care coverage and keep skyrocketing health care costs down. Managed care has controlled costs, a fact the insurance industry touts and doctors concede. Where they differ is how managed care affects the quality of health care. But just how widespread are managed care abuses? "That's the problem. Nobody really knows," says Bettina French of the hospital association. While complaints can be counted, what constitutes a horror story is subjective. Jerry Prete, for one, says expense was the only reason his HMO did not refer him to a specialist or authorize surgery. "All of the decisions that they made, their biggest concern was cost, not care," he says. Indeed, politicians find stories like Prete's compelling. Illinois' foray into the managed care debate is only one of a number of state-based regulatory efforts. Last year, 13 states enacted comprehensive managed care reform. In the 1996-97 legislative session, 31 more were considering similar reform of managed care, according to the Washington, D.C.-based Health Policy Tracking Service. The proposals range from consumer protection efforts to more business-friendly measures. Among the states passing comprehensive reform this year are Idaho and Arkansas. Illinois lawmakers have so far chosen to take a piecemeal approach. Last year, they approved legislation requiring longer hospital stays for mothers following childbirth. This year, they debated requiring longer stays for women who have had mastectomies. Yet, legislation by body part hasn't made anyone happy. "Trying to legislate this type of thing, it's clumsy. It doesn't allow for the individual decisions of the doctor," says Dr. Jane Jackman, president of the Illinois State Medical Society. Richard Coorsh, spokesman for the Health Insurance Association of America, says, "It's easy for legislators to address a perceived problem by passing legislation that does not affect state coffers." Comprehensive reform has emphasized controlling how managed care covers patients rather than specifying what those plans cover.

Such efforts are not entirely new to Illinois. The Managed Care Patient Rights Act — a proposal backed by the medical society — was introduced last year but failed to get out of committee. Though lawmakers resuscitated the measure again this year with more than 30 cosponsors from both parties, it failed to get a vote on the House floor. Rep. Tom Cross, an Oswego Republican, was a cosponsor of the measure this year and last year. He says competition between medical interests and business for specific provisions kept the bill from being called. That fate befell many reform measures, including the bill backed by Illinois businesses. Managed care reform would be a bitter pill to swallow for representatives of Illinois business, and they have been reluctant participants in the debate. Regulations, they say, amount to mandates that increase the cost of their insurance plans, an increase that will be passed on to consumers. Rather than absorb the higher costs, they argue, businesses would have to limit the health care options they give employees or drop health insurance altogether. "You're actually taking away choices under the guise of giving more choices," Alan Peres of Ameritech told members of the Senate subcommittee on behalf of the Illinois Chamber of Commerce. If there is any agreement about managing managed care in Illinois, it is only that the system needs to be reformed. How reform — especially comprehensive reform — is to be achieved is the elusive and unanswered question. Jerry Prete shies away from the politics of the debate. He's heard the arguments from business and the insurance industry. What he knows is his own experience. After disenrolling from his HMO, Prete got the surgery he needed and, with therapy, learned to walk again with the aid of two canes. Legislation, he says, could prevent situations similar to his from occurring. "We've regulated auto insurance and everything else. We ought to pass bills for managed care." Illinois Issues June 1997 / 29

| |||||||||||||||