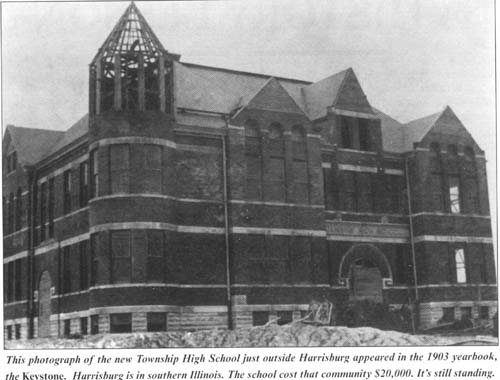

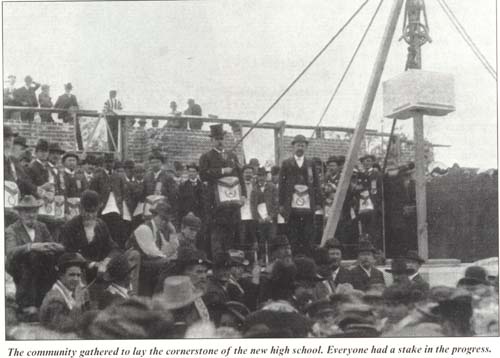

Guest essay A HISTORY LESSON'A good school is a great help to a community' by Carol McDowell Frederick My paternal grandmother, Grace (McHaney) McDowell, attended high school at the turn of the century in Harrisburg, a small mining town in Saline County in the southernmost part of the state. The year she graduated, the community was putting the finishing touches on its new Township High School. Grace's 1903 senior yearbook, the Keystone, announced the school was under construction "on a beautiful site just outside the southern edge of our city, and will be fitted with all modern conveniences." The building cost $20,000. It stands today. When my grandmother was a student, people believed in the power of education to help build a healthy community. Everyone had a stake. The yearbook's pictures of the new school building and of the ceremony to lay the cornerstone reflect the school's importance, and the town's pride in its progress.

Of course, the 1903 Keystone captures the usual time-dated moments,

meaningful only to those who remember. It includes the class will and the

class prophecy, along with photographs of students, teachers, the

football team, the homes of school

board members, the Methodist parsonage and the inside of Parker's Drug

Store. The advertisements reflect the

fashions and nostrums of another

time. The senior yell, as nonsensical as

today's rap music, is preserved, too.

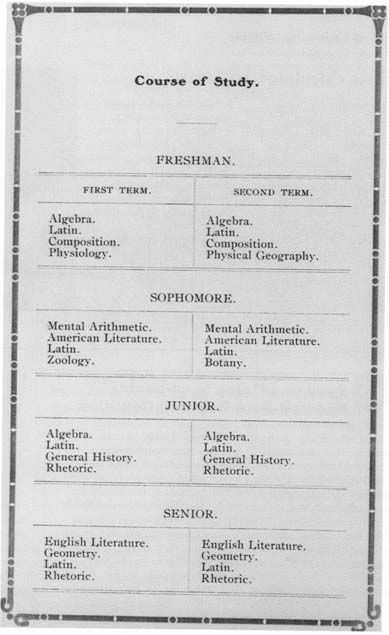

Hi rickety bo. Hi rickety bo! But the yearbook also spells out what that community expected of its schools — and of its students. The curriculum published in the Keystone, including four years of math, Latin and English, as well as physiology, zoology, botany and history, was comparable to a college degree today. As a result, the high school produced graduates who were well-rounded and competent enough to distinguish themselves when they went on to institutions of higher learning. They could compete successfully with students from larger, "big city" school systems. My grandmother, who was the secretary-treasurer of the class of '03, was one of 17 seniors listed in the book. The family names of many of those graduates — Gaskins, Skaggs, Pearce, Gregg, Parker, Whitley, Reynolds, Parish, Ingram and Davenport — are still familiar. Their class motto: "Success does not come, it is made."

But while everyone still has a stake in our schools, fewer people seem willing to pay the price. Repeated failures of local school referendums demonstrate that there is a worrisome lack of Illinois Issues June 1997 / 35

Illinois Issues June 1997 / 36 agreement among voters that "a good school is a great help to a community." Last April, 76 school referendums were held in the state. Only 28 of them passed. The citizens of the Harrisburg school district held their most recent referendums in 1987. Those, too, went down to defeat. When voters were asked whether they wanted to raise the tax rate for school buildings and for transportation, they said no by an overwhelming margin. Meanwhile, the yearly legislative struggle over school funding merely reflects such sentiment. Lawmakers fear a backlash for raising taxes. In truth, many voters appear antagonistic, if not outright defiant to the concept of free, public education. Our public schools appear to have lost the support of the public. Illinoisans, it seems, have lost the spirit of commitment to a universal education for all children evident earlier in this century.

The world my grandmother knew is gone. The social environment that lent itself to a more personal commit ment to future generations is too. The hope is that we'll find ways to engender a new sense of responsibility for a different kind of "community." Perhaps the best way to do that is by recalling earlier values that fostered commitment to our public schools. Carol McDowell Frederick, who grew up in Harrisburg, runs her own lobbying firm in Springfield. Illinois Issues June 1997 / 37

| |||||||||||||||||||