GOOD BOOKS IN BAD TIMES

Richard Shereikis is professor emeritus

of English at what is now the University of

Illinois at Springfield. He spends his

summers on an island in Wisconsin and his

winters in Evanston. He contributes reviews

and essays to such publications as Illinois

Issues and Illinois Times.

If there's a future for real books, it's

in places like Champaign, Carbondale and DeKalb

Essay by Richard Shereikis

"We read to understand, or to begin to understand.

We cannot do but read. Reading, almost as much

as breathing, is our essential function."

— Alberto Manguel, A History of Readin

To steal a notion from Charles

Dickens, you might say these are the

best of times and the worst of times

in the American book publishing

business.

If you're a bottom-line type, you

could look at the record-breaking $20

billion in U.S. book sales last year and

argue that things can't get much better.

With huge book superstores drawing

hordes of browsers and cappuccino

sippers to shelves and tables blooming

with books, you might assume we've

really become a nation of readers. But

a look behind the glittery facade

reveals another truth.

To serious readers and writers,

these are the worst of times, in which

celebrity "authors" (think Dick

Morris, O.J., and Paula Barbieri, for

openers) get millions for books they

may not have read, let alone written;

and where juggernaut book chains

like Borders and Barnes and Noble

steamroll their competition and drive

out good books with bad, discounting

stacks of schlock (tables full of

Princess Di bios, for example), while

letting provocative works of serious

authors languish for lack of

promotion.

This is "the dark heart of the [publishing] empire," as an editorial in a

special issue of The Nation called it

last spring. But while the bulk of that

issue explored the deplorable state of

America's book business, the editors

saw a ray of hope in operations like

university presses, where "literate

people produce books rich with meaning, motivated by an old-fashioned

love of art and ideas."

If there's any future for real books in

America, then, it lies outside the major

publishing houses, which are now just

tiny specks on the landscapes of huge

conglomerates like Time-Warner,

Viacom and Rupert Murdoch's News

Corp.

Given the values of that sordid

world, lovers of "old-fashioned art

and ideas" will have to look for sustenance in less glitzy places, like Champaign, Carbondale and DeKalb, where

Illinois' three public university presses

perform the traditional roles of higher

education. At a time when universities

have abrogated much of that responsibility, evolving into something akin to

trade schools or spas, the presses' productions provide generous benefits for

modest investments: They enrich our

culture and advance the frontiers of

knowledge, serving as a stay against

banal commercialism.

You won't find their products on

national best-seller lists, or featured on

Oprah's Book Club, but you will find

their book lists deep and lively, full of

solid scholarship, quirky surprises and

more food for thought than you'll see

down at your local superstore on 10

tables full of commercial pabulum

about cats, dogs, thighs, abs and

mutual funds.

Among the University of Illinois

Press' fall-winter offerings, for example, you'll find scores of books on

subjects ranging from advertising to

women's studies. Depending on where

you open the 40-page catalog, you

might think the press specializes in

studies of Abraham Lincoln, or labor

history, or country music, or sports, or

film, or literary studies, or astronomy,

or contemporary poetry. But even that

varied list doesn't capture the range of

the press' offerings, which evolved

from humble beginnings in 1918 when

a few faculty monographs were

published more or less informally.

Richard Wentworth, the press' director since 1979, credits his predecessor,

Miodrag Muntyan, with turning the

operation at Urbana-Champaign into

a "coherent, major publisher of scholarly books" sometime in the 1940s.

Publications in the New Math were

popular early, and, in the 1960s, the

press had a major financial success

14/ December 1997 Illinois Issues

with the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities, which tested children

under the third grade on their reading

abilities.

At a time when the press' annual

budget was something like $ 1.1 million, the $650,000 brought in by the

Illinois Test provided a sound financial

basis, which enabled the U of I to publish works it thought important but

unlikely to generate much income.

And that's precisely the challenge for

all university presses, according to

Wentworth, in a business where the

mission is to extend the frontiers of

knowledge, not swell corporate coffers.

"We're usually trying to market books

it's impossible to break even on,"

Wentworth says. "But you try to develop some that will sell enough to make

up for the valuable scholarly ones that

won't find a wide audience."

Over the years, the press' full-time

staff has grown to 35, with an annual

budget in the neighborhood of $4 million, around 17 percent of which

comes from the university, according

to Wentworth. (That subsidy is fairly

standard for other public university

presses.) The rest comes from sales,

and from efforts to attract other support. Some of the press' budget comes

from grants or donations from foundations that support specific books or

series, like the Prairie State Books,

reprints of classic regional works.

Some funds come from individuals, as

in the case of a $25,000 gift from a

graduate of the university's history

department to support historical

studies. Occasionally, the home university of an author will lend support to a

specific project, to advance a work it

deems important.

Or a university press can reap the

benefits of finding a surprise bestseller, as the U of I did in 1978 when it

obtained the distribution rights to

Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were

Watching God, first published in 1937.

Catching the wave of interest in

women's studies and African-American literature, Hurston's work sold

38,000 copies in 1985 and has gone on

to sell tens of thousands more, giving

the press the means to publish other

works that may not recoup their

production costs.

"Normally our books will break

even if we can sell 2,000 copies," says

Wentworth, "and we're happy when we

get a solid seller like [Irving Cutler's]

The Jews of Chicago, which has sold

around 5,000 copies."

Even those numbers would cause

contempt in commercial publishing

houses, of course, with steely accountants looking at the billing sheets. But

that's all the more reason to value

efforts like the U of I's labor history

series, for example, which was recently

enhanced by Rick Halpern's Down on

the Killing Floor: Black and White

Workers in Chicago's Packinghouses,

1904-54, which combines traditional

scholarship with oral history to tell a

compelling story about race relations

and American labor history. And without the U of I Press, there would be no

recognition for the fine poets who are

given voices in an ongoing series, some

volumes of which are published in

conjunction with a national program

to identify and cultivate deserving new

talent.

Like its older counterpart in

Urbana-Champaign, the Southern

Illinois University Press in Carbondale

grew from modest beginnings. When

it started officially in 1956, it was

essentially a one-man operation, with

Vernon Sternberg, who had journeyed

to Little Egypt from the University of

Wisconsin, taking on most of the

press' responsibilities: acquiring manuscripts, editing, marketing and shipping books. In its first six months, the

SIU Press had an income of $361, with

an inventory that could be stored in a

single room in the library.

From that beginning, the SIU Press

has grown to its current state with a

12,000-square-foot warehouse, a backlist of more than 1,000 titles, a fulltime staff of 23 and an annual budget

of around $1.3 million. The current

director is John F. Stetter, who came to

SIU from Texas A & M in 1993 with a

strong commitment to the traditions

established by Sternberg and his

successor, Kenny Withers.

One such tradition lies in the area of

rhetoric and composition, in which

SIU books have won awards from the

Modern Language Association, the

Conference on College Composition

and Communication, and the Association of Teachers of Advanced Composition. Another is the unofficial series

of books by and about Frank Lloyd

Wright, some of which have gone

through multiple printings, providing

a financial cushion for other press

endeavors. And for a number of years,

the press has published well-received

work on the film industry, including

Films of the Eighties, which Choice

magazine selected as one of its Outstanding Academic Books in 1993.

Among SlU's more ambitious scholarly projects is its 37-volume Collected

Works of John Dewey, started in 1961

under the supervision of Jo Ann

Boydston, a series which has earned

scholarly approval from the Modern

Language Association. The Papers of

Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John Y.

Simon, are also published by the SIU

Press. That project had reached 20

volumes by 1995.

But Sternberg's legacy and Stetter's

interests range beyond even these

substantial achievements. A series on

Scandinavian studies, several books on

the rights of special populations

supported by the American Civil

Liberties Union, books of literary

criticism and a projected series called

Writing Baseball fall within SlU's

compass, along with a number of

regional books that have been part of

the press' offerings for years.

"We've made a strong commitment

to our region," says Stetter, "which we

feel extends throughout the state and

across our neighboring states' lines.

We'll be publishing a book about Dan

Rostenkowski by a Chicago journalist

[Illinois Issues contributor James L.

Merriner], for example, and we intend

to continue our Shawnee Classics

series," which includes such titles as

Black Jack: John A. Logon and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era and

The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock, billed as

a "riveting saga of scoundrels and

rogues, an audacious cast of river

pirates and highwaymen who operated

in and around the famous Ohio River

cavern from 1795 through 1820."

The varied fare of SIU suggests why

university presses are crucial in a book

world dominated by corporate values.

Illinois Issues December 1997 /15

A publishing house in a large conglomerate wouldn't be allowed to risk

the publication of a philosopher's

collected works, or even the papers of

a crucial figure like Grant, let alone a

look at a quirky bunch of 19th century

bandits. But that variety, and the challenge of adding to our understanding

of ourselves and our culture, is what

makes John Stetter love his work. "If

you can't have fun in a job like this," he

says, "you're probably brain dead." He

goes on to talk about his hopes for the

baseball series, a project proposed by

Richard Peterson, a longtime professor of English at SIU.

|

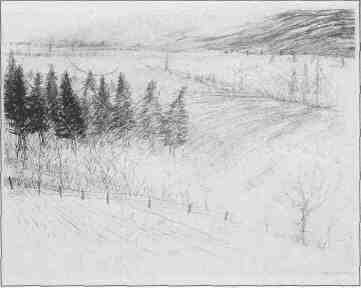

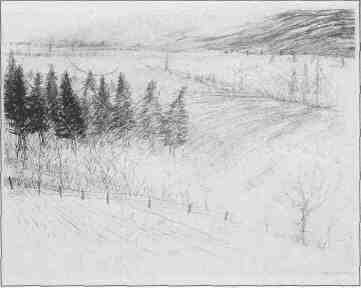

Fred Jones, Macomb

Winter Triptych, 91

1991

|

Like her downstate counterparts, Mary Lincoln, director of the

Northern Illinois University Press in

DeKalb, faces major challenges in a

volatile, commercial book world that

produces best-seller lists contaminated by the works of comedians (Drew

Carey, Whoopi Goldberg and Paul

Reiser, currently), the banalities of

the latest self-help gurus, and soggy,

formulaic novels. It's a world, too, in

which academic libraries have con

spired to damage publishers, reducing book budgets in order to spend

more on computers and other

technological gadgets designed with

built-in obsolescence.

Even so, Lincoln remains optimistic

about the future of her business.

"Actually, this is a good time for university presses," she says, "although we

have to develop a broader educational

mission. We've always been strongest

in literature and history here, and we

mean to continue that tradition, along

with our emphasis on regional studies.

But we're looking for books that might

have appeal beyond the scholarly community, like one we have in production

now by David Young, a journalist, on

the history of public transportation in

Chicago."

|

Young's book would complement

others related to the city, like Roger

Biles' Richard J. Daley: Politics, Race,

and the Governing of Chicago, and

Paul Kleppner's widely praised, solidselling Chicago Divided: The Making

of a Black Mayor, an examination of

Harold Washington's career. And it

would relate thematically to NlU's

Railroads in America series, which

includes histories of specific railroad

lines (The North Western and The

Corn Belt Route, to cite two) and a

number of anthologies on railroad

work and travel.

Not that NIU has abandoned more

specialized academic works, which

are evaluated by outside reviews, a

practice common at all three public

universities. Its fall 1997 list includes

Elisa Kimerling Wirtschafter's Social

Identity in Imperial Russia, along with

a half dozen other, earlier titles in the

press' Russian Studies series, which

has been reviewed favorably in The

New York Times Book Review. A

strong backlist of books in anthropology is enhanced by Elizabeth

Fuller Collins' Pierced by Murugan's

Lance: Ritual, Power, and Moral

Redemption among Malaysian Hindus,

the kind of traditional scholarly

study that will find a small audience,

but might have implications beyond

its immediate subject.

NlU's budget is about $750,000 a

year, with a full-time staff of eight.

The press has about 260 titles stored

16/ December 1997 Illinois Issues

throughout the campus in basements

and central stores. Lincoln estimates

the total number of volumes in the

tens of thousands.

Lincoln's optimism about the

prospects for NIU and the other university presses is tempered by her concern about the role of market forces in

the publishing business. "It's hard to

get exposure in the Borders and other

superstores," she says, "when they're

interested in big best sellers and they

have policies that make it hard for us

to work with them."

|

|

Major chains have been threatening

to charge between 1 percent and

3 percent of the invoice price for each

book returned, which would hamper

smaller presses' ability to give their

books exposure. But Lincoln hopes

that more aggressive marketing will

help university presses maintain a

presence in the superstores while they

continue to get exposure through

catalogs and the dwindling number of

independent book sellers — mostly in

urban areas near universities — which

are still interested in modest profits

for responsible work.

And, like Stetter and Wentworth,

Lincoln sees a silver lining in recent

developments among cutthroat commercial publishers. Last summer, for

example, HarperCollins shocked the

book business with its announcement

that it was canceling contracts on 106

titles. The company's claim, in most

cases, was that the authors had missed

deadlines, which, in the book business

is more the norm than the exception.

Like other publishers who had done it

less dramatically, HarperCollins had

rid itself of obligations to books that

it had decided wouldn't be profitable,

regardless of their merit or potential

significance.

|

Many of those authors went scrambling to find new homes for their manuscripts, and university presses may

become beneficiaries. "We normally

get around 300 manuscripts a year,

and we publish about 20 titles," says

Lincoln. "But we've seen signs that

that number may rise, and we've

already received at least one submission that we believe was among the

HarperCollins cancellations."

The future for university presses

may be brightening, in other words,

despite the smothering effects of

shrinking library book budgets,

schlock-dominated superstores and

commercial publishers who only want

blockbusters. If serious writers want

to tell their stories, argue their cases or

remind us of our past, they'll have to

look farther afield, to publishers for

whom "old fashioned art and ideas"

are still important.

And readers like Alberto Manguel

will have to look a little deeper to find

books that will sustain them. If, as

Manguel puts it, reading is akin to

breathing, the most bracing air for real

book lovers may be coming from independent and university presses, in

places like Champaign, Carbondale

and DeKalb.

Illinois Issues December 1997 /17

Where words really matter:

Illinois' independent presses

Curtis Johnson has been called

the "granddaddy of the underground literary movement" and

"almost the last of the angry

men/angry writers of conscience in

America."

|

Rhondal McKinney, Normal

#1322 from the series "Illinois Farm Families"

|

He's fiercely independent, a novelist, short story writer and essayist

who has fought for nearly 40 years

to keep alive the flame of independent publishing. When the founding

editor of December gave the magazine to Johnson in 1958, it had 17

subscribers. By the time December

ended its run in 1981, it had given

voice to such young writers as Joyce

Carol Oates and Raymond Carver,

and Curt Johnson was only losing a

couple thousand dollars a year on it.

But Johnson sustained the spirit

of December in the press of that

name, which he still runs out of his

Highland Park home. He has published some of his own works

through the press, and some of

those have been picked up for distribution by bigger publishers. His

recent Wicked City — Chicago:

From Kenna to Capone, which has

earned favorable reviews in mainstream publications, will be distributed by the Da Capo Press out of

New York, which gives Johnson

hope that he'll see some financial

returns for his effort.

|

Johnson is too seasoned, though,

to believe that current conditions in

American publishing give any

grounds for optimism. "Things are

exponentially worse now than they

were even a few years ago," he says.

"Let me tell you a horror story. I

had Wicked City finished about five

years ago, and I gave the manuscript

to an agent. He liked it, and he

shopped it around, got it to a

reviewer who liked it too. And then

he asked me for a prospectus! I said,

'What the hell do you need a

prospectus for? You've got the whole

book.' And he said they didn't want

to bother reading the whole book.

Can you imagine? A publisher not

wanting to read a manuscript?"

Which is when Johnson decided to

publish Wicked City himself. And

why he tries to help other writers

who, he believes, deserve to be read.

He's published novels like Jerry

Bumpus' Anaconda, "about a drunk

in southern Illinois," according to

Johnson, and The Second Novel by

Norbert Blei, a prolific essayist and

fiction writer from the Chicago area

18/ December 1997 Illinois Issues

who is now the scourge of developers and other predators in Door

County, Wis.

Johnson's feisty independence is

the sort that makes the universe of

small, literary presses lively and

interesting. There are at least 100

such operations in Illinois right now

— it's hard to track the number

exactly — and their names alone

suggest their range and variety:

There's Black Ice Books in Normal;

Stormline Press out of Urbana; the

Thorntree Press in suburban Winnetka;

Tia Chucha Press in the heart

of Chicago; the Black Dirt Press,

which you can contact c/o Midwest

Farmer's Market at Elgin Community College; and the Third World

Press on Chicago's South Side.

|

|

Together these small, often precarious operations give voices to writers

who have things to say about our

lives, our histories, our neighbors

who may be different from us. And

they usually do it as labors of love,

because it's a tough business competing with corporate publishing

houses that dominate displays at

your local Borders or Barnes and

Noble.

Ray Bial, who operates the

Stormline Press out of Urbana, is

one of those who gets satisfaction, if

not profits, from helping deserving

works get into print.

"What you see coming out of the

big commercial publishers today

isn't worth the paper it's written

on," says Bial, who works full-time

as a librarian at Parkland Community College in Champaign. "It's

just tabloid journalism in book covers: O.J. books and things like that.

They [the commercial publishers]

don't care about the culture of

books, about any kind of social

community."

|

So in 1985, Bial made an effort to

enrich the culture of books. He's

published The Alligator Inventions,

poems about his Cajun heritage by

Dan Guillory, an English professor

at Millikin University in Decatur;

and First Frost, poems about rural

life by Kathryn Kerr, both of which

have received warm reviews. Stormline's most recent title is Guillory's

When the Waters Recede, an account

of the Great Flood of 1993 and its

impact on four river towns that suffered from it.

"Getting books reviewed in

national publications is a key to getting any kind of sales," says Bial.

"We have an arrangement with Iowa

State Press, which distributes a few

of our titles, and we have a mailing

list which helps some. But getting

review copies to library journals and

places like that is the most important thing a small press can do to

generate interest and get some

orders."

Like most small publishers, Bial

isn't able to give his writers advances

Illinois Issues December 1997 /19

or high payments, but he does try to

help them realize some income from

their work. "We either give them 15

percent of whatever we bring in over

the cost of printing the book, which

means we have to sell about 1,000 to

1,200 copies," says Bial. "Or we just

let them have copies, which they can

take to readings and conferences

and sell on their own."

|

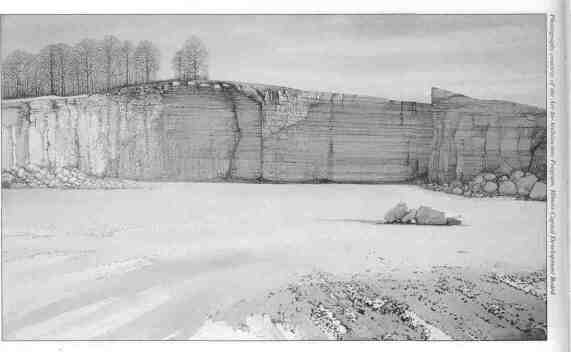

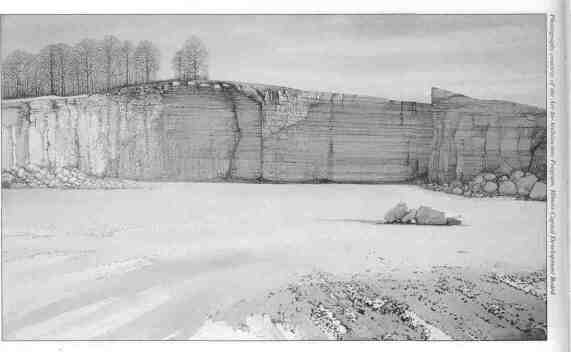

Kevin Booton, Springfield

Florence Quarry

1990

|

Either way, no one makes a living

from operations like Stormline.

"Now that the big publishers look

mostly for the entertainment angle,"

says Bial, "there's no market for the

old mid-list authors [like the Carvers

and Oateses]. University presses are

doing some really good scholarly

books, and they are moving into

things for more general readers. But

there's still room for good things

from small publishers, and it's great

to have an opportunity to help

writers find readers."

|

For the most part, Illinois' small

publishers operate in a Darwinian

world, in which they survive or

expire based on their sales alone.

But the Illinois Arts Council has

helped more than one such publisher develop a project or sustain

the operation. Rich Gage, who monitors the IAC's literary projects,

believes that small presses in Illinois

are "stronger than ever now,"

despite — or maybe because of —

the pressures from commercial publishers. Publishers like the Dalkey

Archive Press in Normal, and Tri-Quarterly, which has blended with

the Northwestern University Press,

are publishing serious fiction and

nonfiction. Three or four years ago,

a Dalkey book was nominated for

the National Book Award. And a

publisher like the Tia Chucha Press,

which is the publishing arm of the

Guild Complex in Chicago, a kind

of literary arts center, has done

about 20 volumes of poetry, mostly

by persons of color.

The IAC has helped these activities, with substantial grants to

Dalkey and Tia Chucha in recent

years, and with awards to various

literary organizations last year totaling more than $140,000.

Given the barren soil of the mainstream American book business, the

world of independent publishers

may be the only place where any literary flowers can bloom. While

Rupert Murdoch's and Ted Turner's

people are screening prospectuses,

people like Ray Bial and Curtis

Johnson will be reading actual manuscripts, looking for honest talent.

And when the next Carver or Oates

emerges, you can bet it will be from

the fertile soil of small publishers,

where literate people still have

respect for art and ideas.

Richard Shereikis

20/ December 1997 Illinois Issues