NOT JUST FOR THE REFRIGERATOR

Art teachers are fighting the perception

that what they do is a frill.

They're making progress

by Jennifer Davis

Five minutes ago, 6-year-old Kemi

Arogundade was running around the

playground with her friends. Now

she's in Mrs. Kichinko's first-grade art

class at Springfield's Dubois Elementary School intently coloring her

lemon yellow "Mr. Sunshine."

|

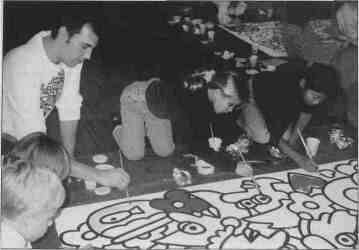

A student at Springfield's Dubois Elementary

School illustrates her own hook in art

class.

|

This "Mr. Sunshine" has purple eyes

with inch-long spiky eyelashes, a pert

nose and dangling earrings. Kemi

cocks her head, selects a blue crayon

and fills in the full lips. The colors she

has instinctively chosen vibrate

against each other, jumping off the

page. The dark daggers in the background, Kemi calmly explains, are

birds. The black streaks? Rain.

At her table, the other children chatter. They share crayons, critiques. But

Kemi is immersed in sweeping her arm

across the page. For her, it's obvious:

This is fun, but it's not play.

|

Arts educators nationwide are struggling against the perception that

Kemi's "Mr. Sunshine" is a frill,

nothing more than refrigerator art.

They've made great progress. Compared to the '80s with its "back to

basics" education movement, this

decade is a mini-renaissance for arts in

the classroom. There's money, research

and interest where there was none just

a few years ago.

|

Dubois students get instruction from a visiting artist on how to make hooks.

|

The change is due in large part to a

1990 wake-up call that rallied art communities across the country. That year,

then-President George Bush and the

nation's governors announced national

educational goals, including a core

curriculum to be stressed through the

year 2000. The arts were absent. The

message couldn't have been more clear.

Arts educators issued an equally

clear response. Shortly after the arts

were overlooked, then-U.S. Secretary

of Education Lamar Alexander was

speaking in his home state of Tennessee. A school choir was scheduled

to perform, but the curtains parted to

reveal an empty stage. That embarrassing and deafeningly quiet moment

struck home. The arts are now

included in our national goals as essential subjects, along with English,

math, science, foreign languages, civics

and government, economics, history

and geography.

|

Still, the momentum from that

grass-roots effort hinges on what happens in the near future. Earlier this

year, a national sampling of eighth

30/ December 1997 Illinois Issues

grade students were tested in the arts

for the first time in two decades.

Preliminary results could be available

soon. Final results are expected next

spring. In Illinois, a statewide sampling of fourth-, seventh- and 11th-

graders were tested in the arts last

spring to get a baseline. A new,

improved test will examine another

sampling of students next spring.

|

Testing the arts, even on a small

scale, is a huge victory for arts education. "It's sad, but true. What gets

tested, gets taught," says Doug Herbert, director of arts education for the

National Endowment for the Arts.

Ironically, say some, arts education

may benefit more if our children do

poorly. Herbert recalls the American

public's shame when testing showed

our students didn't know basic geography. Increased attention resulted. So,

conversely, good test scores could

mean the arts will have to fight harder

to prove their worth.

|

A side walk artist

|

It's a local battle. President Bill Clinton can praise the value of a well-

rounded education that includes the

arts. U.S. Secretary of Education

Richard Riley can say it's "at the heart

of education reform in the 1990s." Art

educators can say the arts teach creativity, problem solving and teamwork. But if local school boards don't

agree, that means nothing. Herbert

notes another motto in education that

many superintendents hold dear: "In

God we trust. Everybody else better

bring their data."

|

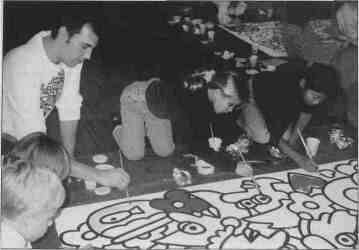

Artist Charles Houska helps students with a painting.

Six of the student paintings now grace the walls at Springfield's Dubois Elementary School.

|

The arts — dance, music, theater,

drawing and painting — are not

geared toward quantitative documentation. And, until recently, such

research didn't exist. "Proof that the

arts are important started to emerge in

the late '70s and '80s," says Nadine

Saitlin, executive director of the

Illinois Alliance for Arts Education.

"Prior to that, the arts were really

targeted as being a frill. In the '80s,

anything that didn't smack of the

three R's was considered irrelevant to

schooling."

Cam Davenport, fine arts coordinator for Springfield's District 186,

remembers that time. When he taught

art at Springfield's Lanphier High

School in the '70s, there were four fulltime art teachers. Then came the '80s

when there wasn't even one full-time

art instructor at the school. Today,

there is one full-time and one parttime instructor.

|

"Fifteen, 20 years ago, Springfield

used to have a string program," marvels Davenport. "It was an amazing

opportunity for kids who might not

otherwise have had that exposure. The

district even provided the instruments.

I came across them in an old middle

school shower room that's now used as

a storage area. I saw these beautiful

violins and cellos propped up against

these shower walls and heard this drip,

drip, drip. It was eerie and sad."

He pauses. "We still own a number

of them. I keep them, thinking someday we'll pull them out, fix them up

and use them." A longer pause. "That

may not be in my lifetime."

He sounds tired. Still, Davenport

does what he can. "I always tell new

art teachers, 'If you're not up to a constant struggle, don't come here.' It's

not enough to have knowledge about

how to teach the arts. You have to be a

strong advocate. I also tell them, 'We

can fight all day with administrators

and boards of education and not grow

an inch. Our best route is to be proactive and engage the community —

parents first.'"

Two months ago, Davenport and

about two dozen other representatives

of Springfield arts organizations tried

to rouse community interest with a

first-ever arts education roundtable.

They sat in the Masonic Temple basement, surrounded by propped-up art

Illinois Issues December 1997 /31

posters and pamphlet-laden card

tables and brainstormed with the

audience, a good-sized group of

parents, teachers and students. Mrs.

Kichinko, Kemi's teacher, was there.

The first obstacle mentioned? Money.

Mainly, the lack of it.

|

Schools don't have many options

when it comes to funding the arts.

They can allocate dollars in their base

budgets or apply for arts grants from

the Illinois Arts Council, a statewide

agency with a $14.1 million budget to

promote Illinois art. This year, the

council has about $650,000 to spend

on arts education statewide.

The Illinois State Board of Education also gives grants, but only to K-6

programs. This fiscal year $499,700 is

available. About $1.5 million was

requested. Still, it's a start. "For a

number of years, the state encouraged

schools to develop an arts curriculum," says Merv Brennan of the

state board. But only in the last decade

has the board backed that encouragement with cash.

|

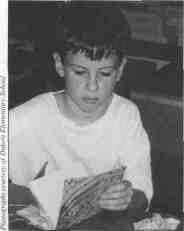

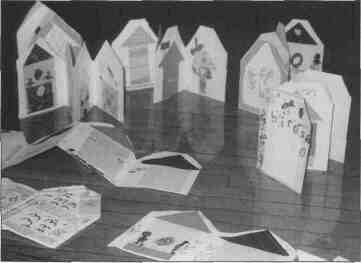

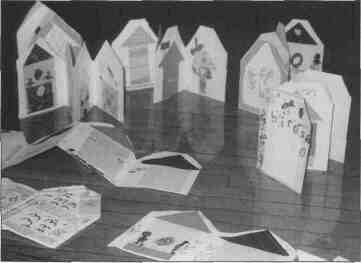

The students at Springfield's Duhois school learned

first how to make the paper

for their hooks.

|

There are no federal funds earmarked for arts education per se by the U.S. Department of Education,

but new Goals 2000 money — a significant chunk at $410 million this

past fiscal year — could help fulfill

arts-related goals. Schools have great

flexibility with that cash, says Sarah

Howe of the federal education department. The only hitch? Unlike other

federal education money, which is

automatically distributed under a formula, states have to apply for those

funds. Illinois got $16.6 million in

Goals 2000 money last fiscal year.

But, because schools could use those

dollars to address a variety of needs,

only the Tazewell Regional School

District specified an amount for arts

education: $28,225. Three other districts planned to use some of their

grant dollars for fine arts, but

amounts weren't specified.

|

Then the students were allowed to give their imaginations free rein

in writing and illustrating their books. The students were guided by artist Nancy Vachon.

|

But money isn't everything. "If a

community wants arts education,"

says Joanne Vena, director of the arts

in education program at the Illinois

Arts Council, "they'll have it, regardless of the dollars."

The arts are a priority for Cliff

Hathaway, principal of Dubois,

Kemi's school. But Dubois is not

wealthy. Hathaway's office is a cubicle

pushed back into a corner — no real

walls or door. The school's 100-year-

old halls are beautiful. They're filled

with plants and children's drawings,

with painted popular cartoon

characters and photos of students

dancing. Hathaway went to school

here. "My first memory," he recalls,

"is of my mother walking me to

kindergarten, and my teacher was

there playing the piano."

|

In addition to Martha Kichinko,

Dubois' full-time art teacher, this

grade school continually brings in

guest artists. Two years ago, Charles

Houska helped the students paint six

large pieces that now grace the walls.

He himself painted a striking 50-foot

black-and-white mural that curves

across the school's library. And,

earlier this year, Nancy Vachon taught

the kids how to make paper, which

they then turned into books they

wrote and decorated. Fourth-grader

Sarah Spilker has fingerpainted the

cover of hers in purple and burnt

orange. A blue feather and some

sequins peek out from the inside,

which is filled with poems.

|

Night

lot of stars

shining brightly at night

hardly breathing at all

stars

|

For the past several years, Dubois

has used grant money to pay for those

guest artists. This year, for the first

32/ December 1997 Illinois Issues

time, the school's parent-teacher organization is picking up the $4,000-plus

tab.

The books the children made are a

good example of using the arts to

teach other subjects. That's something

Dubois strives to do on a daily basis.

On Hawaii Day, the fourth-graders

pretend to fly to that Pacific island,

and, once there, they learn to dance

the hula and make flower necklaces,

or"leis."

|

"They learn the culture, and it's

fun," says Mrs. Kichinko, who has

taught 30 years' worth of art students.

Until the Industrial Revolution,

the arts were integrated into every

subject, says Herbert of the NEA.

"Before the turn of the century, learning was a seamless whole," he explains.

"It was when we started putting

people on assembly lines that we

developed a penchant for compartmentalizing our curriculum. Really,

there is an affinity between the

scientist and the artist. Einstein knew

that."

Arts educators are now starting to

prove that link in a way that parents

can appreciate: research.

Musical instruction has been linked

to higher SAT scores, and related

research continues to surface. In February, another such study said musical

instruction results in increased spatial

reasoning. Chicago Public Schools

CEO Paul Vallas gave opening

remarks when the study's authors

visited Chicago two months later. He

said then that the arts "will not be

sacrificed on the altar of high

academic standards or on the altar of

other core curriculum subject areas."

|

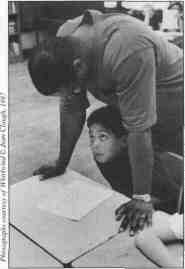

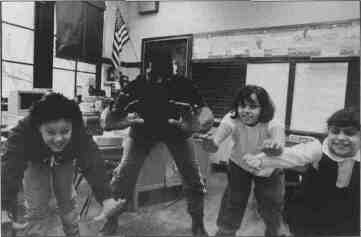

Whirlwind drama artist Little Tom Jackson gives

a student at Waters Elementary

School some personal attention.

|

In October, Whirlwind, a

Chicago-based group that uses drama

to teach the language arts, released a

study showing its students scored

significantly higher in reading and

reading comprehension than other

students who are not in the program.

Karl Androes, the program's executive director, spent almost 15 years

taking his music, drama and dance

company into schools. Then his son, a

third-grader, helped him see that the

arts could be used as a teaching tool.

|

Jackson leads stretches with students at Pulaski

Community Academy

to warm up their bodies and imaginations.

|

"My son did really well in math in

second grade when there wasn't a lot

of reading attached to it. But in third

grade, suddenly everything — math,

science — involved reading. More and

more of his math was story problems,

which messed him up. Pretty soon he

felt like there was nothing he was good

at. It dawned on me that if our

children can't read, it doesn't matter if

they can dance. They need to get

through school to succeed in life.

Before, when we went into schools,

everybody had a good time and we all

went home. Now we're helping these

kids improve their basic skills."

Androes has discovered that kids

understand and remember stories

better when they act them out with his

drama troupe.

|

Indeed, fairly recent revolutionary

thinking in education shows that

students learn differently. Some

absorb information visually; others

kinesthetically. As artist Georgia

O'Keeffe once said, "I found that I

could say things with color and shapes

that I had no words for." The evolution in the way we approach and value

arts education has been slow, but it

has steadily gained steam in the past

decade.

For now, arts educators are holding

their collective breath, waiting for

those national test scores. Good or

bad, Kemi will still learn about the

arts as long as she's at Dubois. Her

school thinks it's important. Other

schools, however, might not, especially

if testing doesn't continue.

"We're preparing for either outcome," says Herbert. "We'll be ready

to defend ourselves."

Illinois Issues December 1997 /33