SPECIAL FOCUS

Since the landmark 1869 legislation creating park districts, Illinois has benefited

from its unique and award-winning system of public parks and recreational areas

INTRODUCTION BY MALCOLM CAIRNS

| The awakening social concern for worsening urban conditions coupled with the economic promise that parks offered, opened a great opportunity for the rapid expansion of parks in Chicago and, later, many other Illinois cities. |

Politics, social reform and design have combined to produce a remarkable level of support for the provision of parks and open space for Illinois residents. Illinois has more independent park districts than any other state. This political and financial structure for the creation of parks in the state has produced an unrivaled collection of historic park landscapes.

The history of Illinois park design begins shortly after the Civil War. Before that time, there is little evidence in this country of land being designed for public use as park land. Large and small cities alike often had public land set aside during the town platting process. This land took the form of the public green or square, a public landing or market, and school land reserved by law for future construction of school facilities.

The nature of this type of public land was such that nothing ensured its continued existence as open space. Courthouses, town halls and other public edifices often replaced these open spaces. Additionally, most mid-19th-century cities were small. Residents had ample access to woods, lakes, streams and open countryside for relaxation. The industrial revolution, immigration and the associated rapid expansion of cities would affect this ability to seek therapeutic open space, prompting the impetus for creating public parks. Chicago's population, for example, swelled from 20,000 in 1848 to 300.000 in 1870. The city grew with little attention to planning and little provision for parks.

The potential for parks to serve as relief from worsening urban conditions was recognized in the 1858 design and subsequent construction of Central Park in New York. Parks were perceived as a means to encourage orderly expansion of cities, and appeared to improve the economic viability of a district in which they were located. Parks also had become sources of civic pride.

Chicago in 1860 had few public parks in which residents could take pride. The awakening social concern for worsening urban conditions coupled with the economic promise that parks offered, opened a great opportunity for the rapid expansion of parks in Chicago and, later, many other Illinois cities. This era commenced in 1864 with the creation of Chicago's Lake Park (renamed Lincoln Park a year later). Beginning in 1867 the city lobbied the Illinois legislature for permission to create park improvement commissions. In 1869 these efforts were successful, resulting in the West and South Park districts, independent taxing districts created to

September / October 1997 / 23

SPECIAL FOCUS

support park land acquisition and improvement.

This ability to levy property taxes by voter-approved park commissions separate from municipal and county government was extended to the rest of the state in 1893. Prior to this time several park associations had been formed in smaller cities such as Quincy. Following legislative approval in 1893, park districts were created in Quincy, Peoria, Springfield and Dixon.

Chicago further advanced the role that parks have played in the physical and social development of cities in establishing what may be the nation's first system of public recreation centers. Sparked by philanthropic concerns for the plight of the immigrant and poor, from 1900 to 1910 the city created a network of small parks that provided neighborhood-based public services: indoor and outdoor recreation facilities, community centers, public bathing facilities, and a host of social and educational programs. These small parks, designed in the Chicago South Park District by the firm started by Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., and in the West Parks by Jens Jensen, provided a model for a state and national movement for neighborhood parks and playgrounds that continues today.

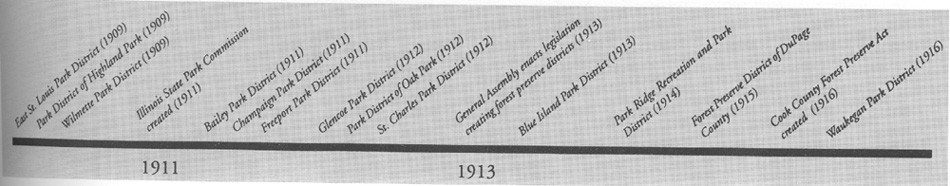

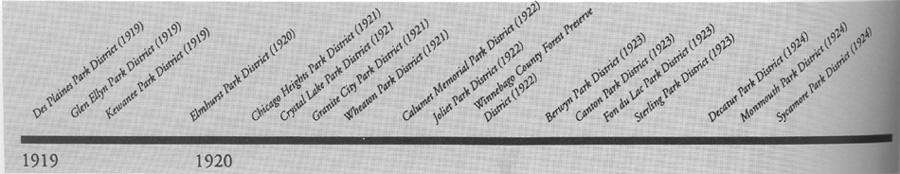

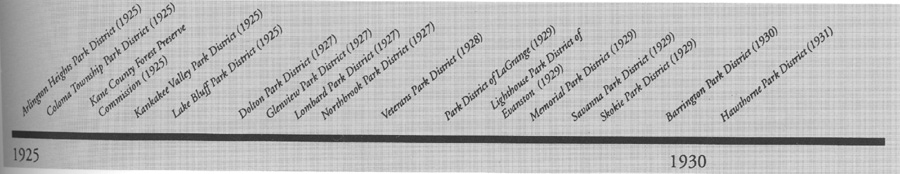

This brief history of parks in Illinois continued when the Illinois State Park Commission was created in 1911. In 1916, 10 years of legislative initiatives were finally successful in allowing the creation of the Cook County Forest Preserve, which solidified public support for the continued provision for a wide array of public open space. From 1870 to 1930, more than 60 Illinois park districts and forest preserve districts were organized.

The expansion and improvement of parks in the modern era began with the 1930s' projects of the New Deal. A drive north along Lake Shore Drive in Chicago from Jackson Park to Montrose Harbor reveals nearly a 15-mile chain of lakefront parkland entirely created by extensive dredging, landfill and plantings, implemented with the labor of hundreds of works paid by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Designs for these lakeshore parks north and south of Grant Park were prepared by Alfred Caldwell. Illinois was second only to New York in the amount of WPA money spent on park and recreation facilities. Over 50 cities had sponsored recreation projects totaling $121 million. Additionally, Civilian Conservation Corps labor created lagoons, drives, and golf courses in many of the region's forest preserves, and extensive facilities in state parks.

This heritage of legislation, which fostered the creation of a strong network of forest preserves and park districts, combined with an outstanding history of contributions from renowned landscape architects and park planners has given the state of Illinois a landscape of public open space and recreation grounds unique in America.

MALCOLM CAIRNS

is on associate professor in the Department of Landscape

Architecture at Ball State University and is the author of The

landscape Architecture Heritage of Illinois which is available for

purchase through the Illinois Chapter of the American Society of

Landscape Architects (ASLA). This article was reprinted with

permission granted by the author and J.K. Communications from the

1996-1997 Illinois Landscape Architecture magazine.

Today Illinois park districts and forest preserves number greater than 370. The quality of park lands and recreational services offered by these agencies has earned Illinois its reputation of having the best public park and forest preserve systems in the United States. Illinois park districts and forest preserves have won twice as many National Gold Medal Awards—which recognize excellence in park management and services—than any other state in nation.

Ideally every agency's unique history would fill these pages. Space limitations make that impossible, so by telling one story for every decade, we hope you'll get a feel for the unique and telling history of the Illinois park district system.

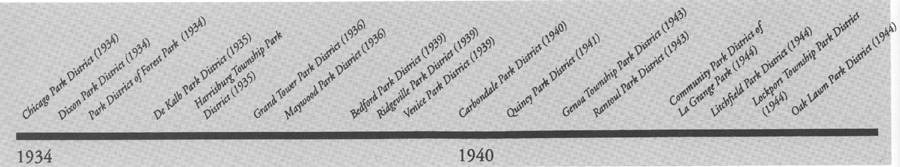

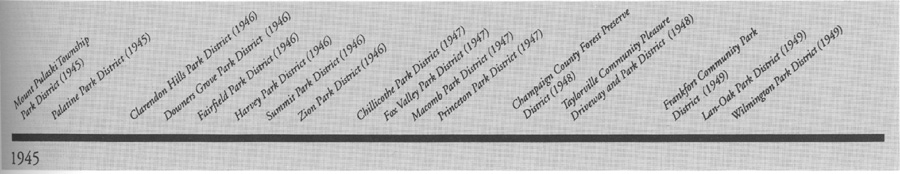

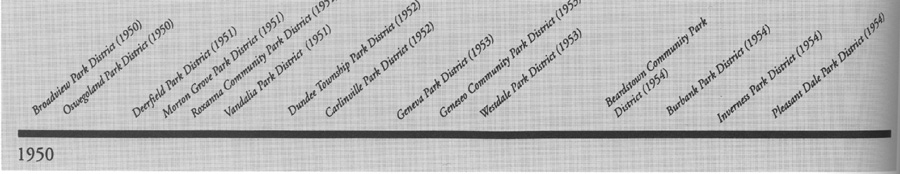

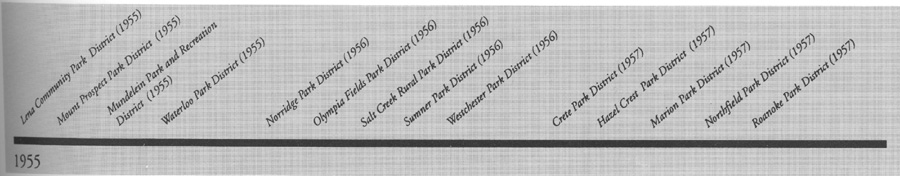

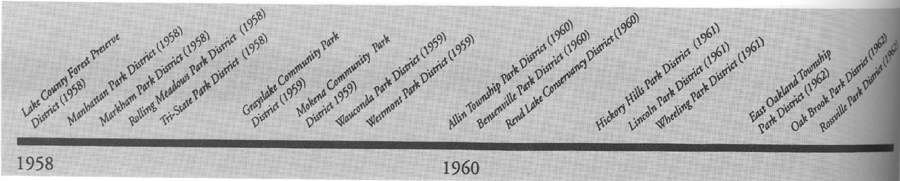

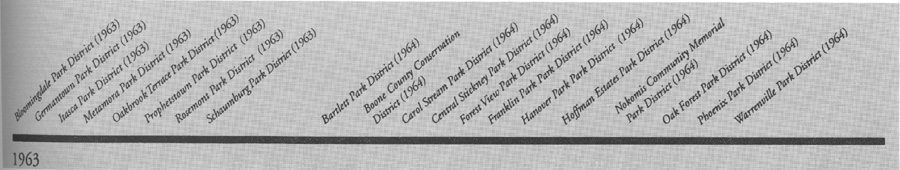

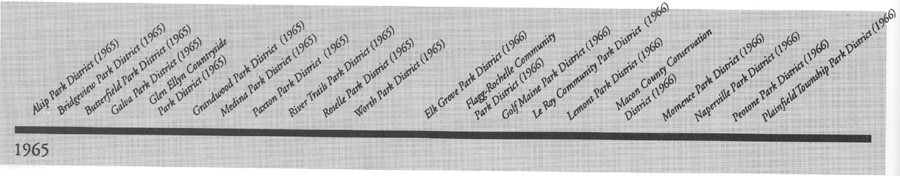

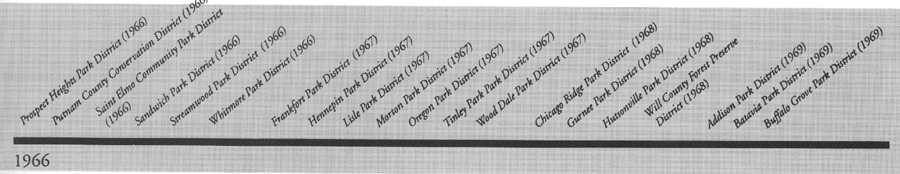

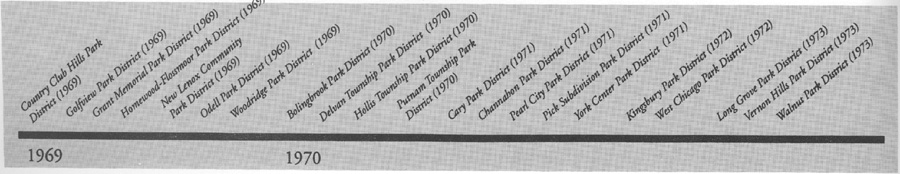

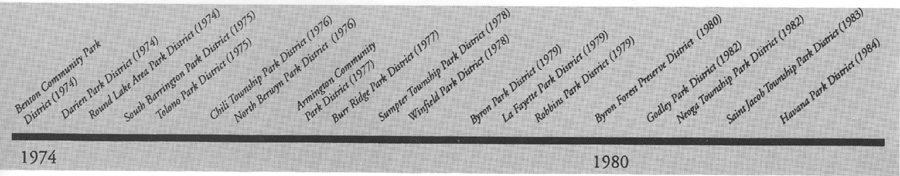

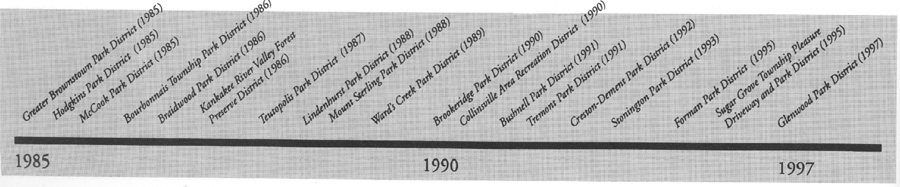

The time line that runs along the bottom of the pages shows the establishment dates of LAPD member park district, forest preserve and conservation district, plus key dates for legislative milestones in the early history of park districts.

24 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

1869

Chicago's Lincoln, West and South Park Commissions

Chicago was incorporated as a city in 1837. Though it adopted the motto "Urbs in Horto" ("City Set in a Garden"), the young city had few official policies relating to the acquisition or stewardship of public open space prior to 1869.

Dearborn Park (which no longer exists) is considered Chicago's first park. It was established in 1839 on a portion of land occupied by Fort Dearborn. Most of the other parks that were established before 1869 resulted from the donation or sale of lands at reduced rates by real estate developers.

In 1849. John S. Wright, a Chicago real estate speculator had imagined a grand scheme in which park development would have a beneficial impact on the entire city. He conceived a city-wide system of grand parks linked together with broad tree-lined boulevards. Though Wright 's idea eventually became the genesis of one of the nations first boulevard systems, at the time it did not become a reality. Rather, the city continued the piecemeal approach of purchasing and accepting donations of land.

By the 1850s growing concern about health and sanitary conditions in Chicago led citizens advocating park development to organize. There was particular concern about the public health threat posed by the "Chicago Cemetery," which was located on the northside lakefront. Due to the water level of Lake Michigan, the graves were quite shallow, and in them victims of cholera and smallpox were buried. Dr. John Rauch, of the Chicago branch of the National Sanitary Commission began leading a protest against further growth of the cemetery. This effort led to the creation of Lake Park, which was renamed "Lincoln Park" in 1865, its boundaries expanded and further burials forbidden.

Between 1865 and 1868 approximately $30,000 was appropriated by the city for landscaping. The donation of a pair of mute swans from New York's Central Park in 1868 became the inception of Lincoln Park Zoo.

While the northside group of citizens were lobbying for the creation of Lincoln Park in the 1860s, two other groups, from the south and west sides were also becoming organized in response to growing concern about the inadequate amount and quality of parkland in their areas. As a result, three Acts of State Legislature were approved in 1869, which established three separate park systems: the Lincoln, South and West Park Commissions. The legislation mandated the boundaries which could be expanded to enlarge Lincoln Park, and the specific lands for parks and boulevards to be established by the South and West Park Commissions.

The South Park Commission was given the responsibility of developing 1,055 acres of property into what was originally considered one park (South Park) and later renamed Washington and Jackson parks. The two sections were linked together by a boulevard, the Midway Plaisance. Land transfers began in 1869 and the landscape architectural firm of Olmsted and Vaux was retained to design the new park.

| Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and his partner, Calvert Vaux (1824-1895) influenced the design of public parks nationwide. Olmsted, who is now considered the "father of American landscape architecture," was responsible for the planning and design of regions, cities and suburban communities, urban parks, parkways, and campuses throughout the United States and Canada. His parks became the prototype for park development throughout the United States. They were large landscapes in which views and vistas could be enjoyed, winding paths could be leisurely strolled on, and meadows could be used for picnicking. The recre |

|

September / October 1997/ 25

SPECIAL FOCUS

ational activities which took place in the parks tended to be very passive, such as lawn tennis and roque, a game similar to croquet.

When an Act of Congress in 1890 authorized the World's Columbian Exposition and awarded its site to Chicago, Jackson Park became the obvious location. Olmsted and Daniel H. Burnham provided guidance to a team of renowned designers through their roles as chief landscape architect and chief architect for the fair. Burnham (1846-1912) is now also noted for contributing to the development of the skyscraper, the field of urban planning, and the City Beautiful Movement.

Later legislation allowed the city to transfer early parks to the three park commissions. One of the most important properties affected by this legislation was Grant Park, which was transferred to the South Park Commission. The land between Randolph Street and 12th Street was first given to the city by the federal government in 1839, with the provision that the land was "public ground, forever to remain vacant of buildings." After the 1871 fire, the area was used as a public dump site, making the first landfill extension of the park from the rubble of the fire.

The Act that established the West Park Commission in 1869 specified the creation of three park sites, each approximately 200 acres in size, with a system of inter-linking boulevards.

There was North Park, which was later renamed Humboldt Park; Central Park, eventually renamed Garfield Park; and South Park which became Douglas Park. William LeBaron Jenney (1832-1807), an architect, engineer, and planner who is best known for his pioneering efforts in steel skeleton construction, received the commission for designing the West parks and boulevards in 1870. Oscar F. Dubuis was appointed as engineer to the system from 1877 to 1892.

By the late 1890s the West Park system had become crippled by political corruption. Though some construction took place, the parks suffered from a terrible lack of maintenance. Change finally came in 1905 when reform-minded Charles S. Deneen became governor. After demanding the resignation of the entire board of commissioners, Deneen appointed a group of prominent businessmen and professionals to serve as the new board. To provide leadership, design direction, and insure honest management, Jens Jensen was hired as chief landscape architect and general superintendent of the West Park System.

| Jens Jensen (1860-1951) was a Danish immigrant who began working as a gardener for the West Park Commission in 1895. Enchanted by the native Illinois prairie, he began a process of experimentation by planting what he called an "American Garden" in Union Park which was composed entirely of native flowers. After having risen from laborer to superintendent of Humboldt Park, Jensen was fired in 1990 after repeatedly refusing to participate in political graft. During the five-year period between his firing and rehiring 1980-1905, he established private practice and continued exploring a naturalistic design philosophy. Eventually, Jensen's work evolved into what is now considered the prairie style in landscape architecture. |

Children in the Mark While Square Wading Pool, 1905 (Chicago Park District Special Collections) |

By the late 1890s a new wave of dissatis faction with parkland in Chicago became prevalent. A new crusade to create more parks was one aspect of a national Progressive Reform Movement. Generated by members of the social elite, the movement focused on the increasing problems associated with Chicago's tremendous industrial expansion. The reformers recognized that the city's existing parks no longer served all of its citizens. The large pleasure grounds were located far away from the overcrowded tenement districts which were in dire need for "breathing spaces." Associated with this effort were social reform ideas about the use of structured active recreation to better the lives of underprivileged children.

The South Park Commission was the first of three park systems to begin establishing parks in the congested tenement districts. In 1890, after a group of prominent Chicagoans had successfully lobbied for the earliest small parks legislation, the South Park Commission began acquiring the 34-acre site for the experimental McKinley Park near the stockyards. Equipped with a swimming pool and changing rooms, ball fields, and playgrounds the new park was an immediate success. This project was guided by J. Frank Foster, general superintendent of the South Park Commission from 1892 to 1925.

The tremendous success of McKinley Park

26 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

led the South Park Commission to engage in a comprehensive program of establishing a system of 14 neighborhood parks to offer comfortable "breathing spaces" in the congested neighborhoods. In addition, numerous services would be provided including public bathing facilities, other health services, educational opportunities including vocational training, social and cultural programs and active recreation.

|

Parks had long since had refectories, boat houses and other buildings geared toward

specific uses, generally oriented towards passive recreation; however, Fosters vision required a building type which would combine educational and social purposes with

that of indoor athletics. The program drew

from the settlement house's concept of social center and the play movement's emphasis on active recreation.

The building type was conceived of as a community center where families could recreate together and, as one commissioner explained, "Keep the boys and girls out of mischief." (Chicago Examiner, February 5, 1904). The fieldhouses generally included a branch of the public library, a lunchroom, club rooms, and assembly rooms. In addition, the buildings enabled active recreation to take place in the parks even during Chicago's bitter winters. |

Jens Jensen's Water Courts,

Garfield Park, ca. 1908 |

The immediate success of the South Park Commission small parks encouraged the fledgling Playground and Recreation Association of America to hold its first annual convention in Chicago in 1907. Before that meeting, President Theodore Roosevelt had issued a public statement suggesting that municipalities send representatives to the conference: "...to see the magnificent system that Chicago has erected in its South Park district, one of the most notable civic achievements of any American City." {SPC Annual Report, 1909)

Between the 1880s and the 1930s Chicago's boundaries were growing as many bordering townships and unincorporated areas were annexed to the city. Thus, growing portions of the city were nor within the jurisdiction of the South, West, and Lincoln park commissions. The residents of the newly annexed areas of the city were impressed by the flurry of neighborhood park construction, and they wanted similar amenities. A new Act of State Legislature was adopted to give these areas of the city an opportunity to create their own park commissions. This Act ultimately resulted in the creation of 19 additional park districts, bringing the total number to 22 by 1934.

Most of the new park commissions were located on the north and northwest sides of the city. Many of these communities were composed of middle class or upper-middle class residents, unlike the poor immigrant communities which the South, West and Lincoln park commissions had addressed. The residents of the north and northwest side communities tended to live in single- family houses or elegant apartment buildings with yards. Thus, the social needs of the new park districts were generally different from those served by the parks of the Progressive Reform Movement.

As the neighborhood parks of the 19 additional park districts began to develop, they were viewed more as an amenity of a good neighborhood and less as a vehicle for social change. These parks had great community significance. The formation of the 19 additional park commissions tended to be generated by groups of residents concerned with the development and welfare of their neighborhoods.

Clubs and the instruction of hobby activities were extremely popular and by the early 1920s most of these parks offered classes in arts and crafts, wood-working, rug weaving, brass work, millinery, sewing, model airplanes, glass blowing, plastic art and photography. Drama instruction and the presentation of plays was also quite common. The fieldhouses generally had large auditorium rooms in which the performances were given. Active recreation was also included in the programming for these parks.

The Great Depression of the 1930s made the unification of Chicago's 22 park districts inevitable. This occurred in 1934, creating the Chicago Park District that we know today.

The Chicago Park District history continues on page32.

— by Julia Sniderman Bachrach, historian for the Chicago Park District. This article is excerpted from Snidermans "Chicago's Historic Parks," which is available in Its entirety by calling 312.747.0551.

September / October 1997/ 27

SPECIAL FOCUS

1894

Pleasure Driveway and Park District of Peoria

As early as March 1868, the value of trees and green space was emphasized in a Peoria newspaper article lamenting the cutting down of a bluff area grove. Several private parks offered residents picnic areas, activities such as croquet and baseball, fountain sodas and ice cream treats, baths—even bears who caused quite a scare when they escaped from their cages one afternoon in 1875. But residents still were concerned about maintaining park areas in the face of developing industry and population congestion.

Peorias growing desire for green space was answered by the Illinois General Assembly's decision on June 19, 1893, to approve "An act to provide for the creation of Pleasure Driveway and Park Districts" effective July 1, 1893. This "green law" addressed, among other things, proper elections, record keeping and ways park districts could acquire land by gift, purchase or condemnation. Peoria was the first municipality in Illinois to seek organization under this new law.

Petitions for a special election resulted in a vote taken on March 13, 1894, with 2,672 voting for the creation of a special pleasure driveway and park district, 1,110 voting against. (Note: This was 26 years before women were allowed to vote.)

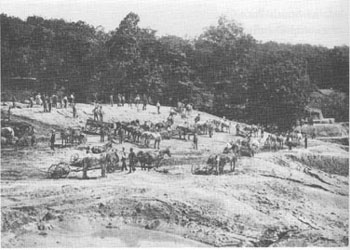

Events then moved very quickly with acquisition of land through two purchases in September (Birket's Hollow, later Glen Oak Park and Madison Park, and South Park); and the hiring of Oscar F. Dubuis, a landscape architect and engineer and a former student of and apprentice to Frederick Law Olmsted. Work began on Glen Oak Park in April 1895. It was dedicated just four months later with an estimated 30,000 people in attendance. More than 2,500 public school children attended the first Field Day held in 1897.

|

Progress continued at a similar pace during the first decade of the 20th century. A miniature railroad opened at Glen Oak Park, ground was officially broken for a drive along Prospect Heights (later to become Grand View Drive and listed on the National Historic Register in 1996), and the first public golf course, a nine-hole course at Madison Park, was opened. Yet another park materialized with Thomas Detweiller's donation of 661 acres in 1927. He donated an additional 80 acres in 1933, making Detweiller Park one of the district's largest parks. In 1945, the district hired Rhodell Owens as landscape architect. Owens was to play a prominent role in shaping the park district throughout the next three and a half decades. |

In January of 1963, the Peoria Park District merged with the City Recreation Department, adding a whole new dimension to the park district's offerings. Growth continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s with the addition of pools, golf courses, Lakeview Museum, an enclosed ice rink, a NCAA soccer complex and a large reservation park. This growth, coupled with the district's excellence in planning and management helped the Peoria Park District earn the prestigious National Gold Medal award in 1971. Owens Recreation Center—the only indoor facility with two hockey-size rinks in a four-state area—was dedicated in 1980 with an appearance by Olympian Dorothy Hamill.

The Peoria community was hit hard, however, in the recession of the 1980s. Approximately 17,000 jobs in the community were lost through layoffs and business closings over a ten-year period. The district's equalized assessed valuation (EAV) dropped 28 percent in the mid-1980s.

This challenge required a shift in paradigms and the district adopted a more entrepreneurial approach to financial planning, Through effective master planning and needs assessments, the district achieved 54 percent of its budget from non-tax revenues, gifts, or fees and charges.

In 1994 the district celebrated its 100th anniversary! Festivities included adoption of a 100-year logo; the naming of our Centennial Baby; placement of a time capsule, and production of a history book. The district also won the National Gold Medal Award that year.

Today, the Peoria Park District has a $20 million budget and encompasses 57 square miles with nearly 9.000 acres in public stewardship, offering more than 2,000 classes, programs and activities each year. Four years into our second century, the Peoria Park District is still going...and growing...Stronger than ever before!

— by Bonnie W. Noble, executive director, and Cynthia S. McKone, marketing director, of the Peoria Park District Photo; The construction of the Glen Oak lagoon was a massive undertaking that took longer than expected ( Peoria Park District 1898 annual report),

28 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

1907

Urbana Park District

The initial drive to preserve and protect Urbana's green space was spearheaded by visionary J.K. Wallick in the early 1880s. As acre upon acre of trees were harvested for lumber for railroad ties and log cabins, Wallick quickly purchased 39 acres of the original "Big Grove" and created Urbana's first private park, known then as Union Park.

The park was advertised as "the most beautiful resort in the state for picnics and pleasure parties." Activities included steamboat rides, boating, ice skating and picnicking. It was also a meeting place for the first of many Chautauquas held in the state. People traveled from far distances to attend these festivities which were highlighted by speakers including William Jennings Bryan, Jane Addams, Booker T. Washington and Captain Cook. In 1897, Wallick traded his park to Benjamin Swartz in exchange for an Indiana farm. The park was then renamed Crystal Lake Park.

The charge to create the park district began in 1902 under the leadership of professor Joseph C. Blair and attorney Franklin H. Boggs. After two initial defeats, voters in Urbana approved the creation of the district on October 7,1907. The first commissioners elected to carry the program forward were Blair, David C. Busey, Justin S. Hall, Charles D. Rourke and Edward Buckbee.

In the district's first two years, land donations included the 39-acre Crystal Lake Park. During the early years of the park district, this park was the focus of activity. On July 29, 1927, the construction of the 880,000 gallon Crystal Lake Pool, the first pool in central Illinois, was completed. Five thousand people, many of whom traveled hundreds of miles, attended the opening festivities. In the '30s and '40s, the park and its pool were so popular that reservations were made in advance to reserve picnic tables.

|

As Urbana grew and prospered, so too did

its park district. By its 50th anniversary, the

Urbana Park District had five different parks

for a total of 114 acres.

The 30 years that followed were intensive periods of land acquisition and developmen as the need to preserve future open space became apparent. Lohmann, Patterson, Prairie, Woodland and portions of Meadowbrook and King Parks and additional land for Victory Park were acquired during the 1960s. In the 1970s, the board of commissioners—faced with a growing and changing population—implemented the first citizen advisory committee in the state of Illinois (known as the Urbana Park District Advisory Committee or UPDAC) With UPDAC's assistance, the district again grew and prospered. |

|

An additional 28 acres were added during the 1980s and many parks were refurbished with new amenities. The construction of the new Crystal Lake Pool was completed at the same site as the original pool in 1980, and in 1986, a complete overhaul of Crystal Lake at a cost of $ 1 million and the construction of the Lake House in Crystal Lake Park were completed.

In 1992, the district learned that its 75- year-old recreation center was structurally unsound and was immediately closed. What followed was an opportunity for the district's board and staff to take a thorough look at the district and, its future. Projects pursued as a result included the replacement of the recreation center, the renovation and expansion of the Anita Purves Nature Center, and the development of its 130-acre Meadowbrook Park. In order to accomplish these projects, the district deemed it necessary to hold a general fund referendum. If the referendum failed, the district would have been financially unable to complete and operate its outlined projects. Support received from the community was overwhelming; the referendum was passed by a 2:1 margin.

The Urbana Park District is now 22 parks strong containing 435 acres. This year marks the districts 90th Anniversary. Celebrations include a party at the Lake House in Crystal Lake Park with hundreds of friends of the park district. Special guests such as residents of the community who are age 90 and older will attend this thanks to Urbana's residents for 90 years of parks, programs and support.

— by Heather Young, marketing and public information

coordinator for the Urbana Park District. Photo: Urbana

Park Pool, a photo postcard from the archives of William

Smith.

September / October 1997 / 29

SPECIAL FOCUS

1912

St. Charles Park District

In the early 1900s the city of St. Charles, located along the beautiful and meandering Fox River about forty miles west of Chicago, was a leading center for relaxation and recreation in the greater Chicago area. The peaceful river and woods, which originally attracted early settlers and wandering Indian tribes, offered many pleasures.

A historian stated that "all work and no play was never the lifestyle of the families who settled along the banks of the Fox." Most of the people came from the East, and, missing the cultured life they left behind, they created their own recreation, including community celebrations of feasting, dancing, and water sports.

Word spread about the attractive Fox River and the area's recreational opportunities, and soon many summer and weekend cottages were built along the river. The town became a thriving summer resort.

One showplace was the Lorenzo Ward mansion, a castle-like residence with a tower. It was built on a beautiful tract of land on the river a few blocks north of the town's main street. The house burned down before 1905, and the Chicago Great Western Railway, which ran a line south of the house, took over the entire property. Fears that the land would be acquired and used commercially led to circulation of a petition to form a park commission to purchase the parcel and develop a public park.

The park commission was formed and on May 20, 1912, the land became the first public park established under the Illinois Park Act. It eventually was named Pottawatomie Park for one of the Indian tribes that roamed the area.

The first commissioners were Bert C. Norris, David S. Wilson, and W.P. Lillibridge, whose terms of office were six years. One of the first projects the new park commission completed was installation of a cement floor for dancing in a picturesque pavilion, built along the parks shore in 1892. North of the pavilion was a sandy beach for swimming and a place for boat launching. Bridges and sidewalks were built throughout the park, and a baseball area was created at the north end.

Just prior to and during the 1910 to 1920 decade, many things occurred to update the area including installation of electric lights, water mains, gas mains, and sewers. Free mail delivery began, a Carnegie library was built, Main Street was paved, and several new industries came to town. The first automobile was driven down Main Street in 1905. In 1910, the Chicago, Aurora, and Elgin third rail electric line company was granted a franchise to run a street car line. This line and the Chicago Great Western Railway furnished the most direct transportation to and from Chicago. All this brought many fun-seeking people to Pottawatomie Park.

Beginning in the 1920s, the Great Depression seriously affected the area. Jobs were scarce and the economy was at a low point. The St. Charles Township park board, with visions of helping the local unemployment situation and, at the same time, improving its park system, applied to the federal government for a grant. A Works Progress Administration (WPA) project of $367,500 was approved with no direct tax or cost to the local taxpayers. This, the largest project in the area, included completion of an amphitheater; baseball diamond and bleacher work; a 9-hole golf course designed by the renowned Robert Trent Jones; a children's wading pool and mammoth (Olympic-sized) swimming pool and complex. To acquire land for the golf course and pool project, many of the summer cottages north of Pottawatomie Park proper were purchased and razed. This was the "birth" of the park district's land acquisition program. At the time commissioners adopted a goal to acquire additional riverfront property whenever possible.

In the mid-1960s, responding to state legislation that allowed park districts to issue general obligation bonds without public referendum, the St. Charles Park District became one of the first districts in the state to pass an ordinance permitting the sale of such bonds. The amount of the first issue was $360,000 to be retired over twelve years.

On April 4, 1967, the voters approved a referendum to change the form of the park district to a general park district. The city of St. Charles transferred its recreation functions to the new district, the tax base broadened, and the board of park commissioners increased to five members. In 1983, by resolution, the board increased to seven members to better serve the needs of the growing population.

St. Charles Park District now operates and manages 52 parks and more than 1,200 acres, including two dedicated Illinois Nature Preserves. Numerous awards have been received for facilities and programs, and the district is a four-time finalist for the National Gold Medal Award.

For many years, St. Charles has been known as the "Pride of the Fox," and it was listed in a recently published book as one of the United States' "50 Fabulous Places to Raise Your Family." The St. Charles Park District contributes much to the community's high quality of life and is part of the reason for the listing. 80

— by Carol Glemza, administrative assistant for the St. Charles Park District. Glemza has been an employee of the district for 55 years.

30 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

1925

Arlington Heights Park District

In the late 1880s in Arlington Heights, the muddy, unsightly conditions of the narrow plots of ground running along both the north and south sides of the railroad tracks brought protests from the townspeople. In response, in 1892, the railroad began to improve them by sowing grass seed. Crews watered the lawns from an elevated tank north of the depot. A windmill supplied the power to pump the water from a well nearby. Volunteer teamsters brought elm trees from Elk Grove Woods to plant in the "railroad parks," and Dr. John E. Best donated hard maples from Klehm's nursery to be planted along Railroad Avenue (now Davis Street).

During World War I, the maintenance stopped and the plantings and grass were left to grow wild. As its prime purpose to clean up the unsightly railroad parks, citizens petitioned for an organized park commission, resulting in the formation of Arlington Heights Park District on June 9, 1925.

In 1883, Dr. Best had given to the village a triangle of land at the intersection of Chestnut, Park and Fremont Streets for the site of a soldier's memorial to be part of the park district. The Business Men's Association donated $1,000 working capital, and an election made it official.

The first elected board of park commissioners included N.M. Banta, A.F. Volz, E.N. Berbecker, Julius Flentie, and Henry Klehm. William Meyer was secretary, and John Bauer, Sr., a retired farmer, became the first custodian of the parks.

In the early '30s, Walter Krause, Sr., donated 11 lots south of Miner Street for Recreation Park. Six more acres were bought, making more than 13.5 acres. The federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) program enabled the town to build the field house and the swimming pool.

To help pay for materials for the grandstand and ballfleld, local officials allowed slot machines in the village. Since this was against the law, the state's attorney put a stop to it, but not before the money was raised.

In 1952, the village attempted to buy several of the railroad parks in order to widen Davis Street and make parking lots. The park board and the citizens were so opposed to the idea that the project was dropped. When the Chicago and Northwestern lines offered to sell five of the eight parcels to the village in 1958, again the opposition was great, but the need for downtown parking was pressing enough that the village overrode the objections and purchased four of the parcels. By the 1960s, all the railroad parks were parking lots.

As the town grew, so did the need for recreation space, and the park district began a concentrated land acquisition program.

|

The federal government declared two parcels of Nike Base land on Central Road to be

surplus in 1964 and the park district was

able to purchase the area now known as the

Kingsbridge Memorial Arboretum, and a

portion of Heritage Park Sale of the Nike

Base land resulted in 12 acres being given to

the park district by the federal government

in 1973, and an additional 52 acres were

acquired in 1974. In 1976 26 more acres

were conveyed to the park district, enabling

the village to develop a golf course and flood

control retention ponds.The Arlington Lakes

Golf Club opened in 1979.

The district continued to add park lands and in 1983 was named the National Gold Medal winner for excellence in park and recreational management. Today, there are 11 parks of more than 20 acres and 47 smaller parks. Lake Arlington, a 93-acrc site, boasts a 50-acre retention lake and an 11-acre native wetland area, and offers sailboating lessons, paddle boats and a 2.2-mile bicycling and walking path. |

|

There are six swimming pools (one indoor at Olympic park), two golf courses (Arlington Lakes and Nickol Knoll), the Sunset Meadows driving range and golf learning center, and the Forest View Racquet Club. In the fall of 1990, the village and the park district jointly purchased the North School play lot and developed the unique and beautiful downtown outdoor recreation center. The district's Historical Museum and the Park Place Senior Center are also administered in conjunction with the village.

The Arlington Heights Park District continues to win awards for excellence. In 1992 it earned the National Gold Medal for a second time; in 1993, a Distinguished Agency Certification; and the Historical Museum has received five Certificates of Excellence from the Congress of Illinois Historical Societies.

The residents of Arlington Heights can be extremely proud of all the park facilities. They add a great deal to the towns good quality of life.

— by Margot Stimely, a columnist for the Arlington Post and a volunteer for the Arlington Heights Historical Society, which is housed in a park district facility. Photo: Arlington Heights train station and first park, ca. 1925.

September/October 1997/ 31

SPECIAL FOCUS

1934

Chicago Park District

The Great Depression of the 1930s made the unification of Chicago's 22 park districts inevitable. By this time hundreds of parks had been created and they were in various conditions and states of completion. Construction and repairs were hindered by severe economic problems, resulting particularly from the decease of the tax base.

In 1934, the Chicago Park District was formed by the consolidation of the existing park districts. By combining forces, the Chicago Park District was able to issue $6 million in bonds to secure WPA assistance for massive improvement programs. Throughout the WPA years (1935-1941) over $ 100 million was spent on Chicago parks.

Significant design work by in-house landscape architects and architects resulted from the WPA programs. Among these were landscape designs by Alfred Caldwell, who has previously worked for Jens Jensen. His work included the Lily Pool at Lincoln Park Zoo (Zoo Rookery), Montrose Harbor at Lincoln Park, and Promontory Point at Burnham Park. The Promontory Point fieldhouse was an important building which was constructed during the same period. Another significant architectural work was the North Avenue Beach House.

During this period, the expansion of cultural and physical recreation programs was re-emphasized under the leadership of George Donoghue, who served as general superintendent from 1934 to 1960. Two lasting programs were the Grant Park Concerts which began in 1935 and the Summer Day Camp Program, organized in 1936. Under Donoghue another act of consolidation occurred in 1959. The boulevards and the Chicago Park District's police force were transferred to the city of Chicago. In exchange, the park district took control of 238 small city parks and playlots.

The Chicago Park District continued to expand its programs in the 1960s. A recreation program for people with developmental disabilities was created and grew into the International Special Olympics. A new land acquisition policy began in the 1970s. The addition of South Shore Cultural Center, Warren and Peterson Parks increased the park districts holdings by 182 acres.

The 1980s saw the beginning of a new era for the Chicago Park District with greater community participation and many innovative programs. Reorganization provided for the decentralization of management, so that decisions could be placed in the hands of local residents. A playlot renovation effort resulted in hundreds of new soft-surface playgrounds throughout the city. Communities are participated by raising additional funds for equipment, or providing labor to build the facilities.

|

In 1986 significant historic photographs,

plans, and drawings were in an administation building basement vault. These archives

have contributed to a renewed interest in the

Chicago Park District's important history and

the preservation of the historic parks.

Today the Chicago Park District owns, operates and maintains one of the most extensive municipal park systems in the world. It includes 27 miles of shoreline, over 7,300 acres of park property, more than 250 facilities, including 9 of Chicago's leading museums and cultural institutions plus Soldier Field stadium (home of the Chicago Bears). |

|

Pre-934 Chicago Park District history appears on page25

— by Julia Sniderman Bachrach, historian for the Chicago Park District. This article is excerpted from Sniderman's "Chicago's Historic Parks," which is available in its entirety by calling 312.747.0551. Photo: Alfred Caldwell's Lily Pond in Lincoln Park, now known as the Zoo Rookery, ca. 1950 (Chicago Park District Special Collections).

32 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

1941

Quincy Park District

|

"(Quincy has) the aspect and ways of a model New England town; broad clean streets, trim neat dwellings and lawns, fine mansions, stately blocks, of commercial buildings

and there are ample fairgrounds, a well-kept park, and many attractive drives...."

-Mark Twain, 1882 |

Quincy settlers were thinking about open spaces for public use when Abe Lincoln was a 16-year-old boy living with his father and stepmother in Spenser County, Indiana. The year was 1825. A center square (now Washington Park) was surveyed and designated for "public enjoyment." Not bad, considering the fact that Quincy's first permanent settler, future Illinois Governor John Wood, did not settle the region until 1822,

And, what a rich history this spot has enjoyed: a former Sauk Indian Village, campground for the Mormons on their way to Nauvoo, and the site of a famous Lincoln Douglas debate held in 1858. Today, the Quincy Park District has 1,000 acres of property, within 34 beautiful areas set aside for "public enjoyment."

As far back as 1888, a group of 32 interested Quincy residents formed the Quincy Boulevard and Park Association. A few years after forming, they pushed through a $1 million public tax levy for the acquisition and maintenance of boulevards and parks. How times have changed; the resulting $5,000 annual budget has grown to almost $5,000,000.

During the early years, the association worked closely with the city of Quincy to acquire several properties for public park use. The first park, Madison Park (8.5 acres), was an abandoned cemetery and still boasts of several beautiful trees planted in the 1840s.

The association had the "modern" forethought to hire a landscape architect (then called a landscape gardener) to "horticulturally" design the park They contacted none other than Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New York City's Central Park, to ask him to be the Madison Park gardener. Some "gardner!" Olmsted was not available, but recommended H.W.S. Cleveland, another well-known gardner at the time. Madison Park was improved to Cleveland's specifications. The remaining parks at the time were all designed and planted by Chicago's renown O.C.Simmonds.

In 1891, the 32-member association purchased beautiful property on the bluffs of Quincy, overlooking the Mississippi River. Today, 16-acre Riverview Park has the character of a "Victorian" park, with brick walkways, stone walls along the vista and ornamental landscaping.

A new era emerged in 1941 with the establishment of the Quincy Park District. From 1945 to 1977, the district's board of commissioners was served by the same five members. This 32-year period of uncanny consistency was known as the "The Long Board" period. All five commissioners have been honored by having significant parks or major facilities named after them.

"The Long Board" proved to be a busy and dedicated group of volunteer commissioners. Also, the same consulting engineer, William H. Klingner, served during this period and continues to serve the present board of commissioners. More than 700 acres of park property were acquired during this time and selective capital development provided a host of diversified recreation and park opportunities still being enjoyed by residents.

Westview Golf Course, a regulation 27- hole PGA rated course, is probably the most noteworthy single facility developed during the Long Board. Westview opened to the public in 1946, and today consists of over 175 acres of pristine, heavily wooded fairways and gentle slopes which accommodate a heavy public use of 60,000 rounds a year.

Mark Twain would not recognize Quincy's riverfront today. Located just a few miles upstream from Tom Sawyers Hannibal, Mo., Mark Twain looked forward to his visits to Quincy and recorded in 1882 that Quincy "had the aspect and ways of a model New England town; broad clean streets, trim neat dwellings and lawns, fine mansions, stately blocks of commercial buildings and there are ample fairgrounds, a well-kept park, and many attractive drives...."

If he were to visit today, he would also, no doubt, record his observations of a beautiful riverfront made possible by a string of well- maintained riverfront parks extending for over a lush landscape of 1.5 miles. Although he would not see the nearly 3,000 riverboats which would pass by on an annual basis in his day, the occasional passenger riverboat still can be seen as it passes by Bicentennial Park, Kesler Park, All-America Park, Edgewater Park, Villa Katherine Park with its own fabulous Moorish Casde and the park districts 130-acre Quinsippi Island, with its 258-boat slip marina and village.

Much of the park property along Quincy's riverfront was acquired in the 1950s; however, development, in earnest, did not start until after the completion of a "Riverfront Renaissance" Study completed of 1989.

Today the Quincy Park District continues the legacy of the past with an active and progressive eye to the future. The districts Comprehensive Plan presents a challenging vision through the year 2020. The vision recognizes that the future of the Quincy Park District relies upon the involvement by all its citizens.

— by Stephen H. Carpenter, executive director of the Quincy Park District

September / October 1997/ 33

SPECIAL FOCUS

1958

Lake County Forest Preserve District

The Lake County Forest Preserves' roots reach back to 1957 and a three-year-old boy who wanted to go exploring in the woods.

When Ethyl Untermyer's son, Frank, made his request, she asked a friend where the nearest forest preserve was. Like many families, the Untermyers had just moved to Lake County from nearby Chicago and were unfamiliar with the area.

She was stunned to hear Lake County had no forest preserves. Chicago's Cook County, after all, had already protected 47,000 acres. So the next day she did what few other 33- year-old homemakers would do. She organized a county-wide referendum to create the Lake County Forest Preserve District.

In those days, Lake County's population hadn't even reached 300,000. But people were already shaking their heads about the loss of open space. Unique to Illinois, forest preserve districts were designed to protect large natural areas. Education and recreation would be important offerings but primarily within that natural context. The concept arose from Cook County in 1915. At that time, Chicago's population was one million and climbing. Leaders were planning for 10 million. Of today's 14 districts, only those of Cook and DuPage counties existed during Untermyers campaign.

Just four people came to Untermyers first meeting. She spoke with groups, sought out local leaders and got a quick education in politics. By election day in the fall of 1958, a ground swell of public support had emerged. The referendum passed with an overwhelming 60 percent of votes. Twenty days later, the Lake County Forest Preserve District was legally established in circuit court. A citizens advisory committee was created, and Ethyl Untermyer was named its chair.

|

And in 1961, four years after Frank

Untermyer asked

for a place to explore, the first Lake

County Forest Preserve was created:

162-acre Van

Patten Woods.

Buying land and providing basic public access were the earliest priorities in the '60s. More than 3,000 acres were acquired, and the first parking lots, trails and picnic shelters appeared. But by decade's end, its first prairie was burned and an old farm field was reforested. Land management had begun. And whether a sign of the times or a natural development of any such agency, Lake County's first ranger went on patrol in 1969. |

"This is the secret, the magic everyone is looking for |

Land acquisition kicked into high gear in the '70s, with more than 8,000 acres added. Many of the facilities and programs that win awards for us today originated then: the Des Plaines River Trail, Ryerson Woods, the Youth Conservation Corps and Lake County Museum. Lake County earned its first national awards at this time, when Old School Forest Preserve combined natural areas and recreation facilities in a way that was emulated nationwide.

Care for the environment was always of paramount importance. Our first of seven properties was named to the Illinois Nature Preserves System, a collection of the state's highest quality areas. And land management intensified, with controlled burns more frequent and resource inventories underway.

By the end of the '80s, the district owned more than 15,000 acres and were offering places to play and learn throughout the county. Environmental education was boosted with creation of Friends of Ryerson Woods. This is when a major shift in land management occurred, as the value of native species and communities was recognized.

By the early '90s the agency had grown from adolescence to adulthood. Computers became as useful and common as shovels. Recreation facilities set a new standard of service for the public. Proactive deer management earned attention and admiration from peers throughout the nation.

New publicity and marketing efforts helped people better enjoy and understand their preserves. Voters embraced another referendum, this time for funds to buy more

34 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORY OF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

1963

Schaumburg Park District

land, restore more natural areas and create more places to learn and have run.

President Clinton signed legislation transferring to the forest preserve—at no cost— a 255-acre portion of the closed Army base at Fort Sheridan. And WW. Grainger, Inc., donated 257 acres of prime land, the district's largest donation ever.

Today, the Lake County Forest Preserves encompass more than 20,246 acres. For two consecutive years, it has been a finalist for the profession's most coveted honor: the National Gold Medal Award.

More than 50 endangered species find refuge on these properties. Hundreds of teenagers pass through the Youth Conservation Corps, and annual attendance at nature programs, special events and nationally accredited museum tops 90,000. The Des Plaines River Greenway has grown to more than 5,100 acres. People enjoy two dozen picnic shelters and more than 70 miles of trails. They play more than 155,000 rounds of golf each year and enjoy canoe launches, campgrounds, fishing ponds, a marina, nature center and more.

More than 1,300 people volunteer here. The staff of 136 full-time and 243 part-time employees includes many award-winning professionals who take pride and satisfaction in their work.

With leadership from president Robert M. Buhai, the 23-member elected board of commissioners and executive director Steven K. Messerli, Lake County continues on this path of success.

And when three-year-old boys and girls want to go exploring in the woods, they now have many places to do it.

- by Susan Surroz, public information coordinator for the lake County Forest Preserves.

Schaumburg is known for its growth. Since the organization of the Schaumburg Park District in 1963, which is a short 34 years ago, the population of the district has more than quadrupled.

The district was organized in 1963 through the insight and understanding of Robert Atcher, who was the mayor of Schaumburg at that time. The village population was less than 10,000. He, along with several other people interested in developing the community, was instrumental in getting the Woodfield Shopping Mall to build in Schaumburg, which gave the district its premiere tax base. He, along with members of boys' Little League baseball (which soon became the Schaumburg Athletic Association), worked with other community leaders who were interested in becoming park commissioners in the design and structure of the corporate limits of the park district.

The district in the mid-1960s was also fortunate in obtaining the services of Paul Derda, its first park director, who worked with the park board in gaining land from the many developers who were building homes, corporations and shopping malls within district boundaries. In the late '60s, a referendum passed that enabled the district to construct a swimming pool and develop some of the 30-plus acres of land that it had at the time into usable play areas and park sites for the fast growing community.

The Schaumburg area was growing so fast that the district had a difficult time keeping up. Many developers were attempting to unload undesirable pieces of property for detention and retention. The park district board and staff, led again by Paul Derda, had the insight to utilize many of these detention areas as multiuse and multipurpose fields. A recreation center was developed

along with another major swimming pool complex with the first 50-meter-length swimming pool, a 60-foot deep diving well, a 10 meter tower, and numerous diving boards and platforms. That pool became a premiere facility for outdoor swimming competition and aquatic programs and activities. By the late '60s the district's assessed valuation had grown by well over 100 percent since its inception. The original $25,000 budget had grown to well over $750,000.

Growth did not stop when the '70s rolled around. The district continued to build more facilities, acquire more property, and the assessed valuation continued to mushroom.

Since 1963, with one swimming pool, one recreation center, less than 100 acres of park land—and the meager amount of money with which it started—the Schaumburg Park District has grown to more than $2.6 billion assessed valuation. It has two golf courses, a 140-acre nature sanctuary with a 20-acre historic farm site, almost 1,200 acres of park land, numerous ball fields, lighted tennis courts and basketball areas, and a cable television station. The district has one of the only indoor aquatic park facilities in the Midwest and has received a variety of awards nationally, regionally, and statewide.

Here in 1997, the Schaumburg Park District continues to grow, continues to look to the future by working with developers, businesses, corporations and with the residents of the community on a variety of advisory committees that the park board has organized. The population of Schaumburg is currently over 78,000 and is projected to reach the 90,000 mark shortly after the year 2000. The '60s were the beginning, but the '90s are certainly not the end.

— by Jerry Handlon, CLP, director of the Schaumburg Park District.

September / October 1997/ 35

SPECIAL FOCUS

1971

Channahon Park District

While the Channahon Park District has only just celebrated its 25th anniversary, the Channahon area could be considered one of the oldest leisure venues in Illinois. Centuries ago, Native Americans named the area "Channahon," meaning "where the waters meet." In southwest Will County, the Des Plaines, DuPage and Kankakee Rivers meet to form the Illinois River. I

Indians traveled to the area for fishing, relaxation, and horse racing. At least two Indian villages were located in the area. One included burial mounds that are listed today on the National Register of Historic Places.

The village of Channahon grew rapidly with the arrival of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, when two locks were built here during canal construction in the 1830s and 1840s. Some 130 years later, the canal also played a role in the formation of the Channahon Park District.

Illinois Department of Conservation (now Department of Natural Resources) holdings included the 25-acre Channahon State Park, a scenic camping and canal trail access point. In 1971, the state was seeking to divest the site from its system, and a successful referendum formed the Channahon Park District to maintain the site as public open space.

Original park commissioners George McCoy, John McMillin, Bill Reece, Jon Scudieri, and Dale Stokes performed much of the park maintenance and early recreation programming, including a summer movie series and annual Easter Egg Hunt.

The park district lease at the site continued for about four years, at which time the park reverted to the state. Fortunately, the district had just acquired, with OSLAD funding assistance, a 120-acre site for a future community park. Emphasis shifted to development of that location, which was aided with a LWCF grant.

The 1980s were marked by expansion of the district's holdings. The park district purchased what became 44-acre Central Park, and a number of smaller park sites were realized through the village's park site contribution ordinance.

The past eight years have seen a series of new capital developments virtually unparalleled in any community, much less one of fewer than 10,000 residents. A strong industrial assessed valuation in the south regions of the 38-square-mile park district, anchored by international corporations Mobil Oil, Amoco Chemical, BASF, Exxon, and Dow Chemical, led to bonding ability that left less than 40 percent of the costs to the real estate taxes of local homeowners.

The award-winning Arrowhead Community Center opened in 1990. The 17,500- square-foot facility houses program and meeting rooms, two racquetball courts, a fitness center, and the district's offices.

In 1993, Tomahawk Aquatic Center—an outdoor water park with a zero depth pool and waterslide—opened and in 1995 received IPRAs Award of Merit.

Heritage Bluffs Public Golf Club, the district's championship 18-hole golf facility, opened in August of 1993. The course was named as one of the 10 best public golf courses to open in the country in 1993 and 1994 and is currently named to a list of the best 75 affordable golf courses in America.

Joining original park district commissioner George McCoy on today's park board are Dennis Clower, Carol Hoffman, Ron Lehman, and Tom Lesniak.

In addition to the park district's 378 acres of land and facilities at 19 sites, area residents and visitors can enjoy thousands of acres managed in the community by the

Channahon Park District 's partner agencies:

• the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor (National Park Service)

• Des Plaines Conservation Area and I&M Canal Trail (Illinois Department of Natural Resources)

• McKinley Woods and Rock Run Preserve (Will County Forest Preserve District)

• the new Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie at the former Joliet Army Ammunition Plant (U.S. Forest Service)

From the 1970-era recreation programming, the district now offers hundreds of leisure programs annually. A program and service guide published three times a year lists activities for infants, seniors, and everyone in between. Community special events include an Independence Day celebration, the Three Rivers Festival, and holiday theme events throughout the year.

The Channahon Park District continues to plan for the future. Among the district's current projects is working on a plan with the local elementary school and library districts for a 50-acre shared site and facility in the rapidly growing western region of the community.

A National Gold Medal Finalists in 1996 and 1997, the Channahon Park District board, its 20 full-time staff, and 155 part- time and seasonal staff take great pride in their leadership role to make the community strong and vibrant with outstanding leisure time opportunities.

— by Charles J. Szoke, director of the Channahon Park District

36 / Illinois Parks and Recreation

HISTORYOF ILLINOIS PARK DISTRICTS

1986

Bourbonnais Township Park District

Lomira Perry probably couldn't have envisioned the creation of two local districts when she included in her last will and testament the words "to be used for purposes of a public park or public recreation area having an area of at least 40 acres,"

Little did she know the controversy that would develop when the state announced in 1984 that they would give the property to a local government agency to follow her request. The next two years of intense debate and disagreement ultimately led to the property being awarded to the newly formed Bourbonnais Township Park District in 1986.

Perry was a descendant of David Perry, who married Martha Durham, daughter of Thomas Durham, the first "American" settler (to distinguish him from the French Canadian settlers) in what was then called Bourbonnais Grove. The 320-acre property owned by Durham had Kankakee River frontage, hardwood timber forest, a crescent-shaped marsh area, natural prairie and a unique geologic historic feature in a 40-foot deep limestone canyon. Legend has it that Native Americans used the canyon caves for shelter, and a cave wall drawing is barely perceptible in the far reaches of one of them.

In her last will and testament, Perry bequeathed the remaining 165 acres other farm property to the Illinois Department of Conservation (now Department of Natural Resources). There were many restrictions and options for the state to use the property. Only 40 acres were required for use as public park space; the remainder could be sold and the profits used to support the park. The remaining tenant, Francis De Voisin, was bequeathed a lifetime option to live and farm the property.

In 1984, the state announced it would give up the property to a local buyer who would present the best plan for its development. The property rested in an unincorporated area bounded by all three local municipalities: Kankakee, Bradley and Bourbonnais. All three agencies were hungry for any development dollars that would add property taxes to their organizations. (At the time, Kankakee County was faced with double- digit unemployment and the closing of several industrial plants.)

Lines were quickly drawn to try to surround the property and allow annexation. No municipality succeeded in this attempt, and years of controversy, debate and public drama unfolded.

Led by Larry Powers, Mark Steffen and Harry Burkhalter, a small group of community members began circulating petitions in 1986 to form the Bourbonnais Township Park District. At the same time, Kankakee County officials circulated petitions to form the Kankakee County Forest Preserve District.

The final ballots cast in the November 4, 1986, election indicated the creation of the Bourbonnais Township Park District by a vote of 3,604 in favor, 1,942 against. At the same time, five commissioners were also voted into office, and at their first official meeting on December 3, 1986, Harry Burkhalter was elected as its first president.

However, in the same election, voters also approved the creation of the Kankakee Forest Preserve District. Now what would the state do with the property? Both presented plans for the property in February 1988 to the state for consideration. On July 27,1990, then Governor Jim Thomson signed a Quit Claim Deed awarding the property to the Bourbonnais Township Park District.

In 1988, the district combined with the Kankakee Valley Park District and the Limestone Park District to create the River Valley Special Recreation Association (RVSRA). Today, the RVSRA serves more than 300 area residents with special needs. In 1989, the park district hired its first employee, Craig Culver, to provide recreation activities. Today, more than 250 recreation programs are held annually without a district-owned recreation facility. And in 1990, it hired Marilyn O'Flaherty to establish a children's museum. Today, more than 45,000 people visited the small 1,800-square-foot facility.

In 1992, the park district was awarded an Open Space Land Acquisition and Development grant to develop the Perry Farm Park. Today, the park has grown to 178 acres. In November, 1996, the park district dedicated more than 30 acres as an Illinois Nature Preserve to protect the geologic features of the Bourbonnais Creek.

In 1996, the park district hired its first executive director, Steve Cherveny. The park district currently has 10 full-time employees. It serves a population greater than 30,000 in a 42-square-mile boundary.

Situated in the next growth area south of Chicago, it anticipates rapid development and is working cooperatively with other villages to assure the future parks and recreation needs of the community will be met.

Several advisory committees have been formed and the board of commissioners Brian Gadbois, Gerald Kuntz, Karen McClure, Harry Burkhalter and Ralph Sims—are preparing to work with the community to provide the best quality public parks and recreation agency available.

— by Steve Cherveny, CLP, executive director of the Bourbonnois Township Park District.

September / October 1997/ 37

SPECIAL FOCUS

1990

Collinsville Area Recreation District

Prior to 1990, the Collinsville area's community parks operated under the city of Collinsville. There were no recreation programs being offered by any public entity and youth as well as adult sports were conducted by private athletic associations not-for-prof- its.

In 1989 a citizens committee involving city park board members, citizens, representatives of the League of Women Voters and the Collinsville City Council, headed by Mary Ann Bitzer, began studying the benefits of forming a park district. Several public meetings were held with visits by park district directors and Dr. James Brademas of the University of Illinois. It was determined that the most desirable boundaries for the proposed park district should take in all of Collinsville Township, providing services for all of the current residents with an adequate tax base of approximately $ 190 million of equalized assessed valuation (EAV).

The proposition of whether a park district should be formed was placed on the ballot at the November 13,1990, consolidated election. Interestingly, the city if Collinsville also placed the question of converting from a commission to city manager form of government at the same election. Both issues passed with overwhelming majorities.

Following the referendum the first director, Richard Dooley, was hired and an intergovernmental agreement was developed whereby the city of Collinsville leased all but one park site to the newly formed Collinsville Area Recreation District (CARD). The district developed a master plan program for the repair and improvement of each property and, since 1990, has made more than $300,000 in improvements.

In 1993, at the suggestion of an employee, Schnucks Supermarket donated 9.6 acres of undeveloped property to CARD. Development of mis neighborhood park was completed with grant assistance from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Schnuck Memorial Park represents the first site developed by CARD and has been a big hit with users and the community.

CARD was fortunate, in 1994, to recruit Mark E. Badasch as its second executive director. The district was going through a period characterized by conflicts with special interest groups, a successful corporate fund rate reduction petition, and legal actions caused by the Schnuck Park Development proposal.

Early in 1995 the district began a strategic planning process to identify areas that park district residents felt should be addressed. This process included several public "Charrettes" designed to offer citizens the opportunity to give input in small groups. The major issues that surfaced were that citizens did not want duplication of services to occur among community organizations; the area lacked a public swimming facility and CARD should be acting to fill this area; and the need for more open space.

Subsequently, the park board acted to investigate the feasibility of developing a public aquatic facility. Again the district asked citizens for input on various issues including facility design, projected range of fees, target user groups and methods of financing. The conclusion of the professional study indicated that development of a Family Aquatic Center was economically feasible.

About this same time CARD was attempting to purchase the school building being leased for office space from the Collinsville School District. However, the school district chose not to sell the building and gave notice to CARD that the lease agreement would be terminated. It was decided that a 7,500- square-foot building should be designed as part of the aquatic complex and would house the administrative offices.

After more than 18 months of planning and design work ground was broken for "Splash City" Family Water Park and the Administrative Office/Activity Building on August 13, 1997. Completion of construction is targeted for the middle of May 1998.

The district also has been working with the Madison County Transit (MCT) District to assist in the development of hiking/ biking trails. Recently, the district was awarded a Bike Path Grant to develop the first phase (3.6 miles) of the Schoolhouse Trail in a joint project with MCT.

Since its beginning in 1990, the district has improved maintenance of existing parks, recreational programs are offered for all ages and, when possible, programs are developed jointly with other community organizations such as the YMCA, Jaycees, area youth leagues and schools. New park lands are being sought and the only public aquatic facility in the Collinsville area is under construction. Staff has grown from only the director and a secretary to four professional staff, four full-time park operations personnel and four permanent part-time employees.

The Collinsville community has witnessed the district become a credible, active advocate for open space and leisure, open to their input and new ideas. Still, as an "infant," the Collinsville Area Recreation District must actively work to bring resources together to serve the community as the millennium approaches.

— by Mark E. Badasch, CLP, executive director of the Collinsville Area Recreation District

38 / Illinois Parks and Recreation