SECRETARY OF STATE?

Why are so many people competing by Jennifer Davis Illustrations by Mike Cramer From the plush, redecorated confines of his second-floor suite, the current secretary of state has a wide view of his domain. One 14-foot window, nearest the marble fireplace and the baby grand piano, faces the Michael J. Howlett Building, named for a predecessor, and a stone wall where some of his thousands of employees are taking a break. Another window, swathed in yards of navy velvet, offers a view of the Illinois State Library, which he also oversees. Indeed, the Capitol itself is under the secretary's control. It's his janitors who sweep the marble floors, polish the rotunda railings. And he decides who can hang banners from that railing, who can rally on the steps outside. Yes, there are lots of trappings of power, beginning with a suite that, despite a 10-foot conference table and big screen TV, still feels roomy. The office is bigger than the governor's, yet the officeholder manages to come across a lot like Norm from Cheers. In fact, that's the best part about being secretary of state. Everybody knows your name. The reason? It's blazoned across the top of each and every driver's license. And the secretary gets to go on television to promote traffic safety, literacy, organ donations. Little wonder then that many consider the post the perfect political stepping stone to governor. And perhaps that's why five candidates are competing for the job in the March primary. The lineup is not only long, it's diverse. On the Republican ticket: two conservative white lawyers from Lake County in the populous Chicago metropolitan region. The Democrats appear to be covering all bets: a woman state senator from downstate Decatur who won her battle against breast cancer but lost a bid for lieutenant governor four years ago; a national hero who took a bullet for former Republican President Ronald Reagan and now fights crime in Orland Park, part of the south suburban area where the contest between Democrats and Republicans is particularly close; and a black Cook County recorder of deeds from Chicago known nationwide for his tumbling team. All of the candidates say they're running for secretary of state because that's the job they really want. Fair enough. But they'll get asked more often than not whether their aspirations really go no further than issuing driver's licenses, filing forms and securing the state seal. And, after all, George Ryan, who holds the post now and is the Republican gubernatorial candidate, isn't the first secretary of state who's had his eyes on the office halfway down the hall. Jim Edgar says he wouldn't have been elected governor if he hadn't first been secretary of state. He used that office to broaden his downstate base as a popular Charleston legislator and state government staffer. "When I became secretary of state, we got involved in the issue of drunk driving and traffic safety, which [former Republican Secretary of State Charles] Carpentier did a little. Drunk driving had been a problem for years, but nobody who had any name recognition or any kind of status in the political community championed it. When we championed it, the media took notice. So it helped the issue, but it also helped me. That's one of the beauties of that office." For his part, Ryan used the post to win a lower drunken driving threshold. While Edgar tried unsuccessfully to get approval of a lower blood alcohol limit during his two-and-a-half terms as secretary of state, Ryan won a reduction to .08 from . 10 last spring, just in time for the election. Edgar also rode the amorphous, but feel-good issue of traffic safety to the top; Ryan appears poised to do the same. And safe driving is the message from the current crop of secretary of state candidates. Republican state Rep. Robert Churchill of Lake Villa wants to crack down on drivers who don't have insurance. Churchill's main opponent Al Salvi, another prominent conservative from Lake County, would get rid of license plates on the front of vehicles. As for the Democrats, it's not surprising that Orland Park Police 30 / January 1998 Illinois Issues

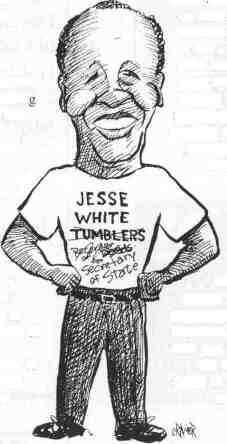

Chief Tim McCarthy is taking a law enforcement approach to the office. McCarthy, who has 22 years with the Secret Service at the top of his resume, proposes standardizing roadside drunk driving tests and making license plates easier to read. Cook County Recorder of Deeds Jesse White would streamline and modernize the office. He says he's done that in his current administrative post, "saving taxpayers more than $3 million a year." White, who is probably better known for the tumbling team he created nearly 40 years ago to keep kids off the streets, would pursue the same goal through the libraries the secretary of state oversees. "Let's put books in our students' hands, not guns," he says. Democratic state Sen. Penny Severns of Decatur would focus on literacy. "Some seek this office for its power," Severns said in announcing her candidacy. "I seek it because of its potential. I wish to solve a profound yet simple problem: At least one in five Illinois citizens cannot read. That must end." But, in fact, the power to issue literacy grants to community groups throughout the state was another key to Edgar's rise. As the Chicago Tribune reported the month after he narrowly beat Democrat Neil Hartigan for governor in 1990, Edgar used his position as secretary of state "to establish a foothold in minority communities by bestowing literacy grants to black groups with increasing frequency." Edgar adviser Erhard Chorle allowed that black support was crucial in the tight race. "What was supposed to be the cushion," Chorle told the Tribune, "became the bench." Ryan took his cue from Edgar's success. About 70 percent of some $5.4 million in literacy grants he bestowed last fiscal year have benefited minorities. In all, Ryan's office issued $73.3 million in various awards and grants, the majority for libraries. In short, the secretary of state's post is the second most powerful state job. And arguably the most visible. Ironically, Edgar says that at the time of his appointment in 1981 he "didn't really want to be secretary of state." He did want to be governor, though. "I always thought, 'Gee, being lieutenant governor would be better.' That shows you how foolish I was, because lieutenant governors don't become governor." Thompson appointed Edgar to finish out the unexpired term of Democrat Alan Dixon. Then, in 1989, Edgar and then-Lt. Gov. George Ryan were both under consideration for the Republican nomination for governor. Though Ryan was second-in-command behind the governor and had served 10 years in the legislature, including a stint as House speaker, it was Edgar's high name recognition and his mini but mighty army of employees/campaign workers that gave him the edge over Ryan. 'I think that helped him considerably," Ryan says now. "His name ID was up. The ability to raise money was there. It made a big difference. So, does it help being in this office compared to being lieutenant governor or some other office? I would guess that's probably true." Now that Edgar isn't seeking re-election and Ryan has plastered his name across the state during his two terms as secretary of state, it's Ryan's turn to try for governor. The secretary of state employs nearly 4,000 people at offices throughout the state, including licensing facilities, the most of any statewide elected official except the governor. The lieutenant governor, for instance, employs about three dozen people in Chicago and Springfield. Though court rulings have restricted the power of state officials to hire and fire for partisan reasons, even hundreds of loyal political workers make the secretary of state a political force to be reckoned with. As political analyst James Nowlan explains, "With that many dedicated foot soldiers, you have Illinois Issues January 1998/ 31

a lot of campaign fund-raising potential." But Nowlan, a political scientist and former state legislator who currently hangs his hat at the University of Illinois' Institute of Government and Public Affairs, adds that only will get you so far. "I believe the office is quite valuable for achieving the nomination in the primary, but becomes of little value in helping the nominee to the governorship." Nowlan also happens to head Ryan's campaign efforts in Stark County. "I think for George Ryan the office [of secretary of state] has achieved as much as it can. For one, it's scared all the other wannabes out of challenging him. But in a general election, where you're appealing to the whole electorate, the role of several hundred dedicated foot soldiers is much less important than it is in the low-turnout primary." History bears out this conclusion. Only two former secretaries of state — Edgar and Louis Emmerson — were able to successfully use the office as a springboard to the governor's mansion. Emmerson, also a downstate Republican, served one term as governor during the Great Depression. He refused to seek a second term. Among those who tried and failed was Democrat Michael J. Howlett. He won his party's nomination but lost in the 1976 general election to Republican James R. Thompson. Democrat Edward Hughes and Republican Charles Carpentier likely would have had their party's gubernatorial support, but both died before the primary. Democrat Edward Barrett lost the 1952 governor's nomination by one vote. However, many men — and so far only men have held the post — did use the secretary of state's office as a stepping stone to other offices, including the Illinois Supreme Court and Congress. Stephen A. Douglas, for instance, was secretary of state for just under three months when he resigned to join the state's highest court. He later served in both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate before unsuccessfully running for president. And Alan Dixon, a Democrat from Belleville, used his popularity as secretary of state — when he was elected in 1978 he was the first political candi 32 / January 1998 Illinois Issues

date to carry all 102 Illinois counties — to propel him to the U.S. Senate, where he served from 1980 to 1992. From the beginning, the secretary of state's office has been a political plum, even when the governor appointed that official and he was little more than a personal secretary to the chief executive. Elias Kent Kane was Illinois' first secretary of state, appointed under the 1818 Illinois Constitution, which he helped write. Historians say Kane, a Yale graduate, had more power than the governor, Democrat Shadrach Bond, who had little education. It's said Kane wrote Bond's message to the first General Assembly along with other papers. "He dominated Bond's administration," according to Keepers of the Seal, A History of Illinois Secretaries of State. Kane later went on to the U.S. Senate. Secretary of state was made an elective post in the 1848 Constitution. And over the years the General Assembly has added to the secretary's duties. In the 1840s, he was both the state sealer of weights and measures and the ex-officio superintendent of common schools. Both duties were later transferred. With the 1870 Constitution, the secretary of state became the custodian of the state seal. In 1891, the office began to administer the anti-trust act and to register trademarks. Even as early as 1892, Secretary of State Isaac Pearson summed up his office by saying, "The nature of this service is entirely new and without precedent in this state." Indeed, the job of secretary of state in Illinois is like no other such post in the country. It is the largest in size and Before the deadline for declaring candidacies, the Reform Party filed competing slates for statewide offices, including secretary of state. The Reform Party is an Illinois offshoot of Ross Perot's organization. Illinois Issues January l998 / 33

scope. "The secretary of state is, truly, the state's secretary," says Dave Urbanek, Ryan's press secretary. "We handle all the minutia that doesn't fall under the governor's office." And, though more politicians have failed than succeeded at making the switch from secretary to governor, the office's potential remains undiminished. For one thing, no other constitutional office is as well-known. If you don't see George H. Ryan's name in your wallet or on your television screen, you might spot it on a sign at a highway toll booth, reminding you about the lower drunken driving threshold, or at the satellite offices dotting Illinois' landscape from Chicago to Albion, population 2,100. "This is the only office interacting with people on a daily basis statewide," says Charles Wheeler III, a former Statehouse reporter who now 34 / January 1998 Illinois Issues

directs the public affairs reporting program at the University of Illinois at Springfield. "In a sense, you're a household word." But Churchill, Salvi, McCarthy, Severns and White will tell you they're itching for the chance to keep track of more than 7.6 million drivers and 9.2 million vehicles as well as nearly 340,000 corporations and almost 100,000 people and companies registered to sell securities, and the state's network of libraries. "It's a fairly complicated administerial office," says Nowlan. "So, if someone really wants to manage people, it's a good office. But, then again, if that's what you want to do, then why not go into private practice and make some real money?" Editor's Note: This candidate lineup was correct at press time. But all candidate filings are subject to challenge with the State Board of Elections. Illinois Issues January 1998 / 35

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||