|

POLITICAL CROSSROADS

Mass transit officials hope to hitch a ride

by Jon Marshall

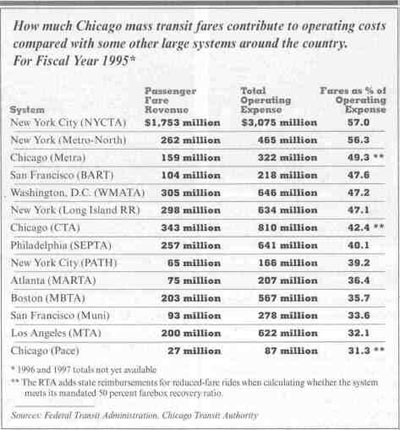

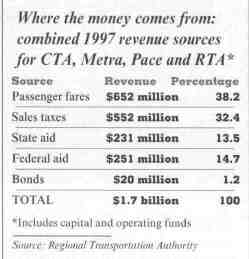

14 / February 1998 Illinois Issues regional transit planning. That figure doesn't include dollars for expansions of the system, he says. Although lobbying efforts hit a dead end last year, McCracken and other mass-transit backers plan to ask the Illinois General Assembly for more money again in 1998. And they've mapped out a strategy to drive the point home. In the past, mass-transit supporters and highway advocates often competed for tax dollars. Now backers of improved train and bus service are trying to hitch a ride with highway interests in an effort to win more votes in Springfield. And they're planning to extend more service to the politically powerful suburbs in an effort to regain riders — and gain supporters. But the CTA, Pace and Metra can't expect a free pass from the legislature. In fact, election-year politics could derail their plans as suburban Republicans and city Democrats jostle for power in Springfield. The most likely source for new funds is a hike in the gas tax or an increase in license plate fees, and legislators are always wary of raising taxes, especially in an election year. Further, many suburbanites, who dominate the legislature's Republican leadership, are not convinced of the value of mass transit in their communities. And many GOP legislators are leery of sinking more money into the CTA, which has been losing riders and money and is largely under the control of the city's Democrats.

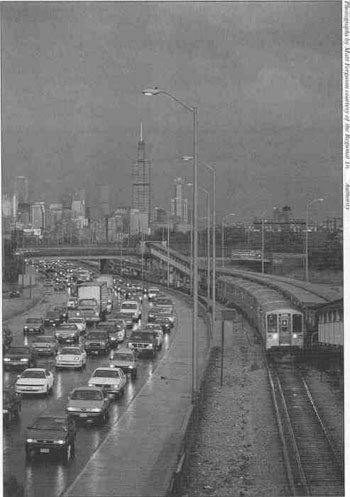

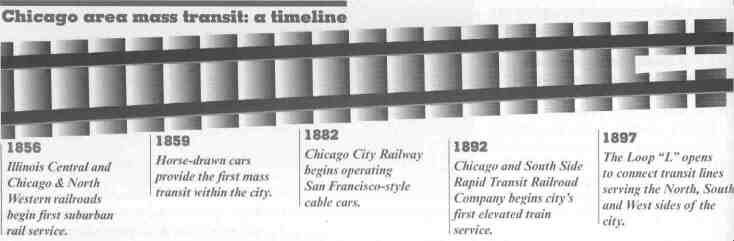

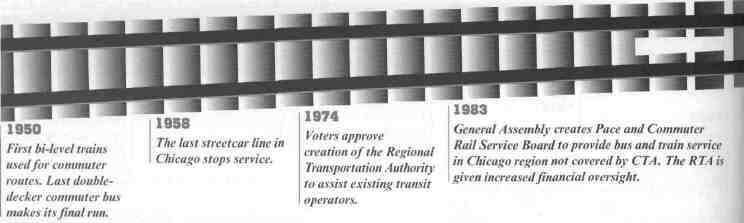

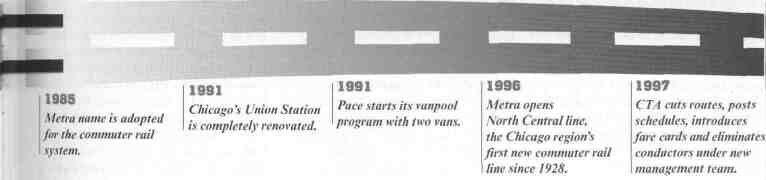

"We're doing our best to combine ourselves with highways to build a coalition," says McCracken, a former state senator and representative from Downers Grove. "I think the suburbs are recognizing we're partners with highways in the total transportation system." Road contractors and business groups are building their own case for more highway spending as Chicago's suburbs spread farther out and traffic increases. A million more cars and trucks are now registered in the six- county region than in 1980, bringing the total to 4.6 million. The number of miles those vehicles travel on an average day soared from 96 million in 1980 to 141 million in 1995, a 47 percent jump in traffic, the Chicago Area Transportation Study reports. Officials at the state transportation department say Illinois' roads need an additional $30.6 billion over the next five years for basic resurfacing and improvements. That doesn't include money for proposed projects to handle growing traffic in the suburbs, including extending the Elgin-O'Hare Expressway and widening the Stevenson Expressway. If nothing is done, potholes and cracks will only get worse, Brown says. Illinois already has 930 bridges and 2,800 miles of roads that are in poor or deteriorated condition and can't get repaired until more money comes through, according to department officials. Backers of improved train and bus service give similar dire warnings about their aging system. "It's slowly rusting out from under us," says Chris Robling, the RTA's communications director. Part of the problem lies with the system's own proud history. The Chicago region's first commuter rail lines opened before the Civil War, and elevated trains began running around the downtown Loop more than 100 years ago. But age began to take its toll. and increasing amounts of money were needed to keep locomotives, tracks and stations in shape. The CTA in particular traveled a bumpy financial path: Over the years, more of its money went toward operating expenses as costs rose and federal subsidies dwindled, leaving less money for equipment replacement. All of that has left a trainload of problems. The CTA says half of its buses need air conditioning, half of its trains need to be rehabbed and three- quarters of its El structure requires renovation. Poor track conditions mean trains must slow down over 28 percent of the CTA's Blue Line Douglas branch that runs through the city's West and Near Southwest sides. Metra reports 244 of its rail cars are older than 50 years and 66 of its bridges are in critical shape. Pace reports it has 348 buses that will need replacing next year. As this transit system grows more Illinois Issues February 1998 / 15 decrepit, it is bleeding passengers. Since 1980 the number of riders on the region's trains and buses has plum-meted from 812 million to 539 million per year, a 51 percent drop. Pace's ridership has remained steady and Metra has gained customers since 1990, but the CTA has seen a drastic decline, especially on its bus lines. The exodus from Chicago to the suburbs has also hurt mass transit. Chicago's population dropped by more than 800,000 between 1950 and 1990, while suburbs in the six-county metropolitan area gained nearly 3 million people. Chicago also lost nearly 400,000 jobs between 1970 and 1990, while suburban employment soared by more than a million. This migration makes it harder for the transit agencies to make their case to the legislature. Most of the new homes and jobs in the suburbs are scattered far from transit lines, prompting more people to rely on their cars, says Joseph Schwieterman, director of DePaul University's Chaddick Institute of Metropolitan Development. Mass transit has a tough time providing reverse commutes from the city to outlying areas and suburb-to- suburb commutes in low-density areas, he says. Pace, for instance, serves a six- county territory roughly the size of Connecticut, making it hard for its buses to reach many suburban neighborhoods. "There are a lot of people [in the suburbs] who feel mass transit is irrelevant to their lives," Pace Chairwoman Florence Boone observes. Boone knows the headaches of commuting between suburbs; she drives from her Glencoe home to Pace's Arlington Heights office because using trains and buses would take three hours. For mass transit to remain relevant, it must ease such long suburban commutes, she says.

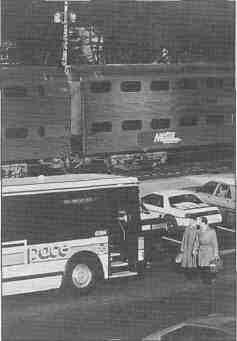

(Right) Reverse commuters board a Pace bus in Chicago's Pilsen neighborhood. But even if it can't reach every corner of the suburbs, a healthy train and bus system reduces traffic for everyone in the metropolitan area, Boone argues. Trains and buses can also carry workers from the city to the growing suburban job market, she says. Many suburbs are showing more interest in mass transit as employers scramble to find qualified workers and residents grow tired of endless traffic jams. Communities in Lake County and northwest Cook County, for example, chipped in money toward the 1996 opening of Metra's North Central Service from Antioch to Chicago. In another ambitious effort. Elk Grove Village, Schaumburg, Rolling Meadows and other northwest suburbs are pushing for an extension of the CTA's Blue Line past O'Hare International Airport and into their job-rich communities. "I think there's a recognition among the suburbs that additional mass transit has to be provided, especially where the jobs are, without adding more roads and congestion,"

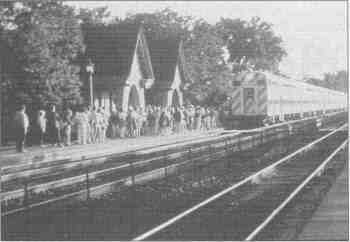

16 / February 1998 Illinois Issues Schaumburg Village President Al Larson says. The transit agencies are trying other tactics to reach out to the suburbs. Metra wants to build a second track for the North Central Line, lengthen its Union Pacific West Line to Elburn and extend its Southwest service to Manhattan. It also is thinking of adding commuter trains to the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern freight line that runs in a semicircle through the suburbs. Pace plans to expand its vanpool program, which provides vans to groups of commuters who handle the driving and pay for their own gas. In addition, Pace and Metra want to offer more shuttle vans from train and bus stops to nearby large employers. And the CTA and Pace are thinking of adding more express buses from the city to suburban job markets as a way to help some of Cook County's 91,000 welfare recipients find work. These efforts to better serve the suburbs could translate into more political support for mass transit. But there are limits to how well these tactics can work, warns David F. Schuiz, executive director of Northwestern University's Infrastructure Technology Institute and a former budget director for the city of Chicago. "It is simply nonsensical [to increase transit ridership] in the vast majority of suburban neighborhoods where the population densities are too low," says Schuiz, who has worked as a consultant for the CTA and the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority.

Frank Kruesi, the CTAs new president, agrees with Schuiz that the emphasis should be on fixing the existing system before spending huge sums on new projects. "It doesn't make sense to expand the Blue Line out to Schaumburg if you can't keep the rest of the line running," says Kruesi, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley's former chief policy adviser. Daley has shown he is serious about reviving the city's mass transit by putting Kruesi — his confidant since Daley was a state senator more than 20 years ago — at the CTA's helm, Schuiz says. The move resembles Daley's takeover of the Chicago public schools, which helped unleash a series of reforms and a flood of new money from Springfield. "I think you'll see a greater willingness of the CTA to embrace change," Schuiz says. "I think there's some light at the end of the tunnel that's not necessarily an oncoming locomotive."

Illinois Issues February 1998 / 17

"Any attempt to address the transportation needs are probably going to require a tax increase [from the legislature]," Metra's Jeffrey Ladd says. Last year, Gov. Jim Edgar's administration floated a proposal to raise $1.5 billion for roads and transit by hiking the state's 19-cent gas tax and raising license plate fees. But the deal went nowhere as legislators spent most of the year grappling with education funding. Transit leaders vow to try again this year. They hope Edgar will emphasize transportation when he releases his proposed budget later this month, the last one in his eight years in office. By linking mass transit money with highway spending, transit officials hope to gain downstate support. And by including suburban projects in their plans, they hope to attract suburban votes. But they understand the realities of election years when legislators are even more reluctant than usual to pass anything that remotely resembles a tax increase. A gas tax or license fee hike probably won't fly with voters until other alternatives are exhausted, says Dick Klemm, the state senator heading the legislative task force on transportation. "I don't know if there will be a package for new funding," he says. But Klemm says his constituents are demanding something

18 / February 1998 Illinois Issues be done about road congestion. "We can't just put our heads in the sand and say our traffic problems will go away," he says. Realistically, the soonest a transportation package is likely to pass is during this fall's veto session or possibly next year when the November elections are safely over, transit leaders say in private. What the General Assembly does will depend partly on what happens in Washington, D.C.,this spring, Klemm says. The Illinois congressional delegation is trying to get a bigger slice of money from the next version of the federal transportation bill, the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, better known as ISTEA. Last fall Congress reached a stalemate as it debated how to renew ISTEA for another six years. "We're hoping for the best [from Washington] but not holding our breaths," the RTAs McCracken says.

McCracken and Kruesi like to point to New York City's subways, where an infusion of state cash led to the rebirth of a system that once was close to receiving its last rites. Sixteen years ago, New York state authorized $3.1 billion in bonds that helped pay for clean, reliable trains to replace New York City's graffiti-smeared, dilapidated fleet. As a result, ridership is now at a 25-year high, according to Railway Age magazine. "What was arguably the world's worst system is now arguably the best large system in the world," McCracken says. The Chicago area, he says, can do the same thing if mass transit and highway interests work together. If they don't cooperate, Illinois will pay a heavy price, McCracken says. Increased congestion on the roads will waste time and produce smog, making the region less competitive in the world marketplace. If people can't get to work and goods can't get to their destinations, Chicago and the state will lose business to other areas with more viable transit systems, he argues. The Chicago area already has the fifth worst gridlock in the country, according to a 1996 study by the Texas Transportation Institute at Texas A&M University. The time and fuel wasted cost the region $2.8 billion annually, the study estimated, or about $370 for every man, woman and child in the Chicago area. This gridlock will only get worse if transit isn't helped, Metro's Jeffrey Ladd says. The trick, he says, is persuading enough people that trains and buses make a difference in their lives, even for suburban commuters who drive. They need to know that without mass transit an extra 1.8 million people would be forced to commute by car every day, he says. "Why can't we have a mass transportation appreciation week?" Ladd suggests with a mischievous smile. "Just shut it down for a week and see the effect on the highway system." Jon Marshall is a free-lance writer who has reported extensively on transportation issues. He catches the train and bus from his Wilmette home.

Illinois Issues February 1998 / 19

|