|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO |

Staff |

Links |

|

STATE OF THE STATE

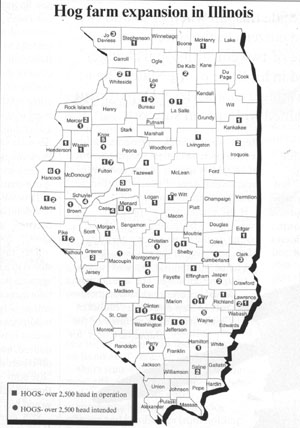

Illinois politicians haven't by Jennifer Davis We know large hog farms stink, and some say they put small farmers out of business. But it's what we don't know that should disturb us. This little piggie went to market; this little piggie stayed home; and this little piggie cried "wee, wee, wee, wee" all the way to the Illinois General Assembly. Indeed, hogs, specifically large corporate hog farming operations, became one of the issues in this year's do-nothing, pre-election legislative session. That was evident in the huffing and puffing in the standing-room-only committee hearings and in the message children delivered from the Illinois Pork Producers Association. "Dear legislators: Please save us from the big bad wolf — local control." Lawmakers considered giving county boards control over the siting of so-called mega-hog farms. And they debated increasing restrictions on such operations, an effort to find balance in industry, environmentalist and public concerns. In the end, they did nothing. For the time being, that may be just as well. Lawmakers appeared bent on plunging ahead with regulations without getting the full scoop on hogs. Will Illinois benefit from the shift to large- scale production? Are the profits staying in Illinois? What will be the long- term effect on the environment? We don't know. Politicians aren't asking. "We recognize that our industry is going to be regulated more," says Mark Gebhards, executive director of the Pork Producers Association. "We just ask that those regulations be based on science, not emotion." Indeed, the issue is unlikely to go away. The National Conference of State Legislatures, a bipartisan education and advocacy association that tracks state government policies, calls it "one of the hottest issues in Midwestern legislatures." "This issue is such a moving target," says NCSL policy analyst Barbara Foster. "We don't have a really good idea right now what's going on in all the states. What we would write today would be changed tomorrow." Such has been the swiftness of change in this industry. "In 1989, a farm with even 1,000 sows was considered big," explains Christopher Hurt, agricultural economist with Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind. "Now, it's not uncommon to see [farms] with 5,000 sows. There are even some with 20,000 within a relatively small area. The very large growth of these operations got ahead of where the science was." And that's what led to the major manure spills in North Carolina, Missouri and Iowa in 1995, he adds. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, such spills in North Carolina have "killed more than 10 million fish and closed nearly 365,000 acres of coastal wetlands to shellfish harvesting." That state has imposed a two-year moratorium on new mega-hog farms in order to conduct a pollution study. And the federal government is considering environmental standards covering large livestock facilities. Meanwhile, the evolution in hog production has brought a large, odorous cloud to the Illinois Statehouse. We know these mega-hog farms stink. (DeWitt County recently lowered the property taxes of 23 people living close to hog farms.) But some say they also run small farmers out of business and pose environmental risks. Yet we don't know for sure. Indeed, there's very little we do know. For example, what is a mega-hog farm? Illinois doesn't have a definition. How many large livestock facilities are there and where are they? Until two years ago, no state agency tracked them. Who owns these farms? We have little to no clue. "We don't require a list of all the investors, just whoever's building the facility," says Patrick Hogan, spokesman for the Illinois Department of Agriculture, the agency that regulates mega-livestock facilities. That means we also don't know who is profiting from the influx of larger operations. Is it an Illinois-based company or is it Wendell Murphy of North Carolina, the largest hog farmer? How much of the $1.04 billion from 1996 hog sales actually stayed in Illinois? "There's no way to gauge," says Garry Kepley, state statistician with the Illinois Agricultural Statistics Service, a joint federal-state office. The University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign recently looked at four multicounty areas, in an effort to find out how hog farming affected each region's cash flow. But the necessary data doesn't exist, says Michael Mazzocco, professor of agriculture and consumer economics. Kepley notes that while Illinois has fallen from the nation's second largest hog producer to the fourth, the number of Illinois hogs "is not down that much. It's just that other states have increased production." 6 / June 1998 Illinois Issues Still, the number of Illinois hog farms has declined in the past decade. In 1988, there were about 17,000 hog operations: About 7,000 operations had 99 hogs or less and about 4,000 had more than 500 hogs. In contrast, last year there were just under 8,000 hog operations statewide, says Kepley. Of those, about 2,000 had 99 hogs or less and about 2,000 had more than 500 hogs. And while the largest farms only make up 31 percent of Illinois' total hog farm operations, they account for 84 percent of hogs raised here. "Each category [of farm] has seen a decrease, but the larger farms have seen less," says Kepley. Yet the Illinois Stewardship Alliance, a nonprofit organization supporting small farmers, argues Illinois is on the brink of being swamped by factory farms. Since last May, the Department of Agriculture has received 133 letters of intent from producers wanting to put in farms with more than 1,000 hogs. The average projected size is 2,900 hogs; whereas, the average existing farm is 540 hogs. "This new information on the number of facilities wanting to come in really does emphasize the need to put a stop order on new permits," says alliance spokesman Chirag Mehta. "It's obvious they want to be grandfathered in just in case the legislature passes stricter regulations." Nationwide, states with few regulations on large- scale hog farms have seen an increase in the industry. Oklahoma's "hog numbers quadrupled in just five years," according to the Center for Rural Affairs, an advocacy and education organization. Further, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says, "several counties in northeast and eastern Colorado have some of the highest concentrations of confined animal operations in the country." And those "animal feedlots are a major source of groundwater contamination." What, if any, are the environmental consequences as this industry moves from primarily small- and medium-size farms to large, concentrated operations?

According to the U.S. EPA, agricultural practices as a whole have caused the degradation of about 60 percent of surveyed rivers and streams. And 16 percent can be traced to animal feeding operations. There are approximately 450,000 such operations nationwide, yet only the largest — about 6,600 — are subject to ERA regulations. But that could change as the federal agency considers requiring more pollution permits. Here, the Illinois State Geological Survey is studying a leaking lagoon located near an aquifer. The exact site is confidential. Since July 1996, the agency has tracked the movement of "some bacteria" as well as ammonia, chloride and sodium from the lagoon, says Bill Dey, associate agriculture engineer with the survey. "There have been a lot of studies in other states, and the literature says these lagoons seal up in two to six months. This lagoon is four or five years old. Either it's not self-sealing or that's taking place more slowly for some reason." Dey notes that the lagoon in question, which has no man- made liner, could not be built under today's guidelines. But how many lagoons like it exist in Illinois? "We don't know. We're trying to get some funds to track them." Dey's group is also looking for more money for the current study, which runs out at the end of this month. And the survey wants to study deep manure pits, which currently are exempt from regulation. "Many producers are going to deep pits," he says. Pork producers argue they are safe stewards and stricter regulations will hurt their industry. That could be true. As Purdue University ag economist Christopher Hurt says: "Who would have thought the U.S. would be an importer of cars 25 years ago? Down the road, we may be importers of pork." But, with all the unknowns surrounding this mutating industry, shouldn't we be asking how Illinois will fare in the future economically and environmentally? "That's a very good question," says Hurt. Illinois Issues June 1998 / 7 |

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |