|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO |

Staff |

Links |

|

CLOUT AND MEDICINE

When politics decides where dollars go for medical research,

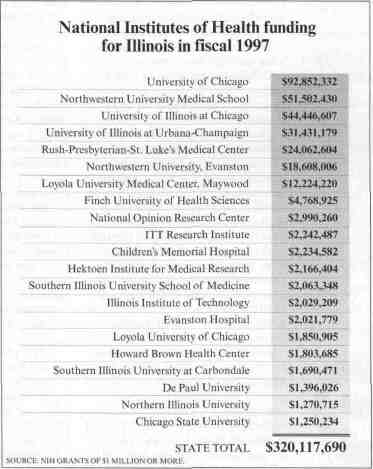

Essay by Howard Wolinsky Back when he was in the U.S. House of Representatives, Paul Simon remembers a phone call from a parent of a girl his son was dating. The girl had cystic fibrosis, the life-shortening genetic disease that clogs the lungs with excess secretions. The parent was worried because funding for CF research was drastically cut by the National Institutes of Health, the nation's premier medical research organization. Simon called the NIH director and found that the agency's top CF expert was retiring and the agency's budget had to be cut, so funding in this area was being reduced. Simon took the issue to his House colleagues. "This was the largest genetic killer of children. I got on the floor and I got an amendment passed. We ended up getting more research money, rather than less." Simon did what any officeholder — from the U.S. Congress to Chicago's wards — would do if a constituent called wanting help with filling a pothole or hunting down veterans' benefits: He used clout. Politics plays as big a role in the multibillion-dollar biomedical research enterprise as it does in defense contracts, albeit on a less grand scale. The analogy is apt: Advocates for diseases war with one another for scarce federal dollars while researchers fight for the money. In research, as in most endeavors, politics is often the tail that wags the dog. Scientists like to think of themselves as being above the fray. But in government- sponsored research, the connection between politics and research is inescapable. Dr. Harold Varmus, director of the National Institutes of Health since 1993 and the 1989 winner of the Nobel Prize in medicine, says, "Obviously, we're a public institution, and we get our money from the Congress and the taxpayers, so we listen to what people have to say. Because we're a government agency within the Administration, we follow directives from on high. We are subject to a variety of kinds of influences from the indirect to the direct." The stakes are high, with lives, billions of tax dollars and even Nobel Prizes at stake. Medical research is big business in America, and advocates would like to see it get even bigger. About $30 billion a year is spent on medical research in this country, approximately half with funds allocated by Congress to the NIH and the remainder coming from private industry and philanthropy, including advocacy groups. Advocates are quick to point out that this is a relatively small amount. After all, Americans spend $15 billion a year to rent videos, Illinois Issues June 1998 / 17

18 / June 1998 Illinois Issues Sometimes members of Congress are statesmen fighting for the interests of the entire medical-research enterprise, which is viewed as a source of Ameri- can prestige and an engine for economic growth. Sometimes, they more resemble ward committeemen getting potholes filled or doling out garbage cans, looking out for their own and themselves by seeking to increase dollars for a pet disease in hopes of winning goodwill that might translate into votes on Election Day — a classic instance of doing well while doing good. Simon, now retired from the U.S. Senate and founder and director of the Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, says funding decisions are determined "in part on the basis of need and in part on the basis of politics." This link between political science and medical science was first observed by pioneering 19th century German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, who noted: "Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine on a grand scale." U.S. Rep. John Porter, a North Shore Republican, concedes there's a bit of politics in everything. But as chairman of the Subcommittee on Labor, Health & Human Services and Education of the House Appropriations Committee, he insists he tries diligently to keep politics out of the budgeting process so that NIH scientists can decide how best to spend research dollars based on scientific merit and public health need. He opposes Congress' telling the agency how to allocate the money by "earmarking" funds for particular diseases or projects. Porter says, "We don't fund by disease. We fund by institute. It has always been done that way. And though Congress certainly has strong opinions on where the money ought to go, it has never crossed the line and said: You must fund this research. It has always left the final determination of the most promising avenues to pursue to science. That is as it should be." Porter's attempts to cleanse research funding of politics wins praise, but some observers believe earmarking still occurs. The annual report from Porter's committee contains not- so-subtle recommendations that the NIH pursue a particular direction in research, sometimes favoring certain diseases affecting constituents or even relatives and friends. The report contains dozens of "encouragements" and "urgings" from members of Congress for research into a panoply of ailments, from the common and well- publicized (hardening of the arteries, Parkinson's disease, eating disorders)

to the obscure (facioscapulohumeral disease that wastes skeletal muscles; Rett Syndrome, a crippling brain disorder in baby girls; and Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia, a rare blood cancer). Insiders claim that the NIH ignores such recommendations at its peril, but Varmus says it's "hard to measure whether anything extra actually happens" as a result of congressional hints. Even so, Michael Langan, vice president of public policy for the National Organization for Rare Disorders, which advocates for the 20 million Americans with rare diseases, says Congress is playing games with such language. "When you go into the committee report language, they say it's not earmarking. But you know what? It is," says Langan. '"We the distinguished committee on appropriations feel that it is very important that NIH spend $100 million on epilepsy or something.' And even though that's not a line- item earmark, not legally binding, it's a very strong suggestion that you better do it, or we're going to be mad at you next year. And you don't want us mad at you next year." Porter contends: "The report that accompanies the bill contains lots of suggestions. They are not, however, mandated. There is an ability to direct the attention of NIH, and there is an ability at times to get them to move in certain directions. We still leave the final decision to science; and we don't politicize it." Still, politics show up. For instance, it's not unusual for Congress to bypass the usual budgetary process to press for funding of a priority disease. Last year, as part of the Illinois Issues June 1998 /19

Ray Merenstein, vice president of Research!America, an umbrella group for health groups seeking more funding for medical research, says the advocates for research into AIDS and, later, those for breast cancer pioneered a new way to increase funding that became a model for other organizations. "The AIDS movement epitomizes [the notion] that if you couple scientific opportunity with loud knocking at the door, it can make a difference," he says. "Successes like protease inhibitors and identification of a breast cancer gene coupled with declining AIDS and cancer rates in the U.S. are proof that more advocacy and more money can make a difference." Sometimes it takes money to make money, even for research funding. Groups seeking more funding for research — such as the American Cancer Society, the National Breast Cancer Coalition, the American Foundation for AIDS Research and the American Diabetes Association — are spending millions to lobby Congress for more research money. Last year, following the example of such power brokers as the American Medical Association, the National Breast Cancer Coalition even went so far as to form a political action committee. The coalition says its PAC spends "a very small percentage of PAC funds [on] the campaigns of candidates who support the organization's mission." Most funds, the organization says, will be used for the Breast Cancer Political Campaign, which educates politicians and opinion leaders and asks them to support the coalition's platform. Research funding advocates and politics make for the usual bedfellows. While the success of advocates for AIDS research changed the political calculus of research funding within Congress, it also, perhaps inadvertently but probably inevitably, altered the political landscape outside Congress. It heightened the disease wars. 20 /June 1998 Illinois Issues In the early 1990s, advocates for women with breast cancer formed the National Breast Cancer Coalition with the goal of being "squeaky wheels" to obtain increased research funding. At an organizing session in Chicago in 1991, Ann Maguire, a breast cancer patient representing the Women's Community Cancer Project in Cambridge, Mass., said, "If we can find billions to bail out the savings and loans and to send 600,000 troops to the Persian Gulf, we should be able to find more money for breast cancer research." Organizers noted that in the first 10 years of the AIDS epidemic, 120,000 Americans died, while at the same time more than 500,000 women died from the "silent" epidemic of breast cancer. Sharon Green, former executive director of the Chicago-based Why Me National Breast Cancer Organization, says advocates for women with breast cancer vowed to use any tactics necessary to advance their cause. Some threatened to bare their mastectomy-scarred chests to Congress; some, for dramatic effect, did pull off wigs to reveal heads made bald by chemotherapy. A new generation of women was contracting breast cancer, and they no longer were satisfied to raise funds and awareness with support groups, teas and fashion shows. "The women who were activists in the '60s were now of the age where breast cancer became a higher risk. You had women who were used to speaking out," says Green, who left Why Me a year ago to become deputy director of the new Illinois Office of Women's Health. In 1991, she spearheaded the coalition's "Do the Right Thing" campaign, with the goal of delivering 175,000 letters to Washington, one for each life claimed by breast cancer. In the end, more than 600,000 letters were handed to Congress and the White House in 1991. "The interest was phenomenal. Women wanted to come to Washington and deliver the letters themselves. Almost every state was represented. This was totally unexpected," says Green. She says the movement benefited from the fact that there were more than one million survivors of the disease. Such a movement had never been possible for lung disease, a bigger killer, that has no community of survivors. In addition, breast cancer not only was a dread disease, like AIDS, but unlike AIDS, which affected shunned minorities, could more easily attract mainstream support. Two first ladies, Betty Ford and Nancy Reagan, had been among those who survived the disease. Showing their own political aptitude, breast cancer groups did an end run around those in Congress, who opposed earmarking research dollars, and breached the "firewall" between civilian and military spending. The coalition found a loophole that allowed funds from the Department of Defense to be spent on breast cancer research. The Pentagon was willing to use some resources to build good relations with the civilian world. The "war on cancer," declared by President Richard Nixon in the 1970s, could now be joined by can-do medical research warriors from the military. The defense department appropriation for the research has been $600 million over the past five years — about 40 percent of what Congress spent through NIH. Although they are men and women of science, NIH administrators are not immune to the political winds blowing from Congress and advocates for people with particular diseases. Porter says: "NIH itself does not exist in some kind of scientific vacuum. They're impacted by the patient advocacy groups. They're impacted obviously by Congress. They're impacted by the American people generally, by the Administration specifically." Meanwhile, the NIH funding process has started to come under congressional scrutiny. At the request of Congress, the National Institutes of Medicine, an affiliate of the National Academy of Science, held a one-day hearing in April to examine NIH's process for setting priorities in funding. Conservatives led by U.S. Rep. Ernest Istook, an Oklahoma Republican and a member of Porter's committee, have attacked that process. Istook

Illinois Issues June 1998 /21 |

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator |