FROM LINCOLN TO FORGOTTONIA

Roads, schools and taxes

have always divided Illinoisans

by James D. Nowlan

Illustrations by Ralls Melotte

You can't do this to me, Pate," declared Richard M. Daley, mayor of Chicago, to James "Pate" Philip, Republican state Senate president from DuPage County. They were talking Chicago school reform in Philip's Capitol office in 1995.

Pate did it to him.

Maybe turnabout is fair play, and good public policy as well. A generation earlier in 1974, Richard Daley's father turned out his political machine to overwhelm strong suburban opposition in a binding referendum, creating a six-county regional transit authority.

So this is the story of how the leaders of the geo-political regions of Illinois have hammered out the issues that shaped the state we have today. Notwithstanding conventional thinking that regional political conflict has been harmful to our state, it appears - strange to say - each region has benefited at the hands of the others.

Is regional conflict an artifact of culture, or of good old-fashioned horse trading? By now, the geographic fault lines that separated the original settlers, the Upland Southerners, the Yankees, and later the hyphenated-Americans, have been fuzzed up, as a walk with your fingers down most any suburban phonebook will tell you.

In the 1830s, however, political battles were fought between Upland Southerners in the deep south of Illinois and their kind farther north, like Abraham Lincoln. In 1832, in his first race for the legislature (unsuccessful), 23-year-old Lincoln laid out three objectives in his platform: an internal improvements system, a system of education and control of interest rates. Throughout our state's history, those issues - transportation, education and finance - have been central to both Illinois policy-making and regional political divisions.

In 1827, Congress granted Illinois 300,000 acres of land to build a canal linking Lake Michigan to the Illinois River. Growth in the north of the state was already being spurred by the Erie Canal, which connected the East to Chicago. Lawmakers from Little Egypt and elsewhere in the south of Illinois, fearful their region would be left behind, became strong supporters of a railroad to link the Ohio River to the I&M Canal. And they were enthusiastic about a whole scheme of internal improvements - railroads, canals, plank roads, river developments - that would crisscross their region.

So in 1837, in a spasm of enthusiasm and logrolling, the legislature voted $10 million in bonds for internal improvements, twice the total tax base of Illinois, with interest payments equal to 10 times the annual revenue of the state. Every county got a road or a bridge or the promise of money. State Rep. Lincoln and his eight Sangamon County colleagues (all six feet or taller and thus known as the Long Nine) were suspiciously supportive of projects elsewhere, especially those of rival Alton, in

Illinois Issues September 1998 | 27

their efforts to relocate the state capital to Springfield.

The scheme fell of its own weight, leaving the state dotted with bridges from nowhere to nowhere and partially dug canals, as Paul Simon put it in his book on Lincoln's years in the state legislature. Only the I&M Canal was completed, and later the Illinois Central Railroad. As a result, it was not Little Egypt in the south as its lawmakers had hoped, but eastern Illinois north to Chicago that was "settled as if by enchantment ... a desert blossomed as the rose with towns and farms," in the words of Theodore Pease in his history of Illinois.

No matter how much ethnic and cultural lines have blurred across the Illinois landscape, Chicago was - and is today - different from the rest of Illinois, in magnitude, energy and politics. And observers and politicians have always played that card.

In 1869, William Lowman of Stark County went to Springfield to lobby for a charter for the Havana, Toulon and Galena Railroad (never built). In his diary he wrote: "Spent an enjoyable afternoon in the House gallery, listening to the lawmakers debate the question of whether to cede Chicago to Wisconsin or Indiana."

"Chicago! Chicago, queen and guttersnipe of cities, cynosure and cesspool of the world," declared English journalist George Steevens while covering the elections of 1896. "Not if I had a hundred tongues, everyone shouting a different language in a different key, could I do justice to her splendid chaos. The most beautiful and the most squalid, girdled with a twofold zone of parks and slums."

Eighty years later, in his first race for governor, Jim Thompson faced Michael Howlett, a jowly Chicagoan who reminded some voters of Mayor Richard J. Daley. "Do you want a governor who is close to Daley?" Big Jim thundered to downstate audiences. "No! No," came the resounding responses.

There has always been this City and the Plain around it, as the National Geographic defined Illinois in June 1967. Fear that this burgeoning city and its county of Cook would control Illinois politics caused the legislature to brazenly violate the Illinois Constitution of 1870, which called for redistricting of the legislature every 10 years on the basis of population. From 1910 until 1954, downstate lawmakers snubbed this proviso, and by 1950 Cook County had 52 percent of the state's population but only 37 percent of total membership in the General Assembly. That was cause for geo-political stress.

The outlanders' fear was warranted. In the 1973-74 legislative session, the Cook County Democratic Party, headed by Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, drew upon his political muscle in deliberations over development of a regional transportation authority to encompass the six counties around Chicago, a plan that would also bail out a financially strapped and patronage-laden Chicago Transit Authority.

By the 1970s, public transit in metro Chicago was in danger of collapse. The Chicago Transit Authority continually ran short of money for its trains, buses and clout-heavy union employees, and the railroad companies were talking about dropping their suburban commuter rail services. Republican Gov. Richard B. Ogilvie created an office of mass transit and called for a regional transportation operating agency. In a special session in November 1973, the legislature acted. With backing from the civic community, and with total support from Daley's Democratic contingent, House Speaker W. Robert Blair and Sen. John Conolly, both suburban Republicans, created the Regional Transportation Authority.

The legislation included a requirement for a region-wide referendum in the spring primary of 1974. The many suburban lawmakers who had opposed the legislation struck a responsive chord among voters with the cry of taxation without adequate suburban representation. Eighty-one percent of voters in the five suburban counties voted against the RTA, but the Daley organization turned out almost half a million Chicago votes in favor, and carried the issue by 14,000 out of nearly 1.4 million votes cast. In part as retribution from constituents, Speaker Blair and Sen. Conolly lost their seats in the legislature that year.

Because of the defection of one suburban RTA member, Chicago was able to name its own transit chief as the first chair of the RTA. But the tables would soon turn. By 1983, the CTA needed further financial help, but Chicago faced a Republican governor, as well as suburban lawmakers angered by sharp boosts in commuter rail fares and the complete shutdown for two months of suburban bus service imposed by RTA Chair Lewis Hill, another Daley man.

Gov. Jim Thompson and Republicans drove a hard bargain. In return for additional funding for the CTA, Chicago ceded control of the RTA board to the suburbs and the power to appoint the chair to the governor. In addition, CTA labor contracts could be reopened by the RTA board, and a new funding formula ensured that most revenue generated in the suburbs be spent on services there.

How has it all worked? "The RTA is one of the most significant accomplishments of the past 30 years," declares Philip. "When I go to campaign at Metra stops [the commuter rail unit under the RTA], voter after voter tells me how much they appreciate the great service."

Thanks, Chicago, Philip fails to add.

Illinois Issues September 1998 | 28

Even so, says Jeff Ladd, chair of the Metra board, "Transportation for the region is a ticking time bomb. A five-cent boost in the gas tax would all have to go for maintenance, yet we just have to provide more service to meet the exploding growth in the region." Ladd details some problems: rail passenger cars a half-century old must be replaced, 700 bridges in the region need work, 60 are on the critical list.

In other words, Illinois still needs "internal improvements."

Government support for education predates that for transportation. The Northwest Ordinances of 1785 and '87 provided that the 16th section (640 acres) of each 36-section township be given to the maintenance of public schools. In 1855, Illinois began using a small slice of its state property tax to complement local support, distributing it on the basis of population. Immediately, Cook, Sangamon and other large counties protested that they paid in more than they received, a concern for getting one's "fair share" that echoes to this day.

In 1920, state superintendent of schools Francis Blair complained that Illinois ranked 38th in the nation in state taxes for education, about where Illinois has ranked in recent years. By his fifth four-year term as state schools chief, Blair lamented the wildly uneven local support for schools, comparing a one-room school in Lake County that had an assessed valuation of $2.4 million in 1926 with one in Wayne County far to the south that had only $10,000 in total property value. In 1927, Gov. Len Small and the legislature responded. Every district would receive $9 per child in attendance, and low valuation districts that levied the maximum property tax allowed without referendum could claim an additional $25 per pupil.

These are precisely the arguments that have framed the school funding debate from then until 1997, when Gov. Jim Edgar and the legislature enacted a major advance in school funding.

"Schools are the biggest issue that sets suburbs and downstate apart," Philip observes, putting his cigar down. "They get more, and we pay more." He's right, of course, and that's what happened in 1997 when elected officials boosted sharply the minimum funding per pupil for children in low valuation districts, from about $3,000 to $4,225, with additional increases built into the future.

State Sen. Arthur Berman, a Chicago Democrat, has been at the forefront of education issues since he entered the legislature three decades ago. "Chicago and the suburbs got a

Illinois Issues September 1998 | 29

few things in this legislation, but the big winners are downstate districts. And this bill was passed with Chicago and suburban votes."

Two years earlier, led by a downstate governor and suburban Republican lawmakers, earth-rattling changes were forced upon the Chicago public schools, which had been mired in mediocrity, if not worse, for decades. Everybody was fed up, but Chicago politicians were strait-jacketed into helplessness by the teachers' union, the operating engineers, service employees and other unions and by a phalanx of African Americans with good jobs in school management. All Chicago legislators, save one, opposed Chicago school reform.

Suburban GOP senators began lobbing mortars onto Chicago school turf in 1993, calling for management reforms that would make it possible to fire bad teachers and give principals authority over their own buildings. But the shells fell harmlessly because Democrats controlled the House.

In 1995, however, the GOP held all the power levers - governor's mansion, Senate and House majorities - and they set to work in earnest to reform Chicago public schools, a world of 400,000 pupils and 600 schools as foreign to this working group of white staffers and law-makers as Outer Mongolia.

Daley could not be for the powerful management and teacher reforms the GOP put in his lap, could never have imposed them. Yet he salivated privately at the prospect, and has made the most of them thus far.

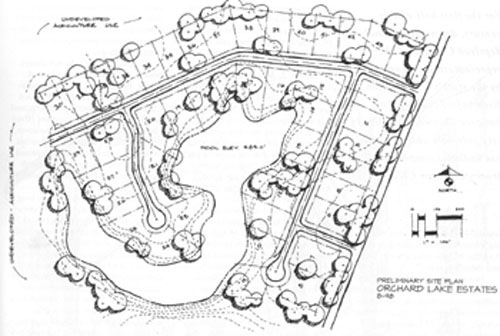

In 1972, Western Illinois University student and gadfly Neal Gamm proclaimed himself "Governor of Forgottonia," as he raised the flag of independence for a 16-county region, declaring that as a separate state western Illinois would be better off. At the time, travelers couldn't get to western Illinois from anywhere else. There just weren't any good roads out there, though the situation is somewhat better today.

Analysts with the University of Illinois and the legislature's own research unit have all concluded, however, that downstate receives a lot more in state spending than it sends to Springfield in taxes, especially western and deep southern Illinois. As former state Rep. Doug Kane wrote in his economics doctoral dissertation in 1975, "The flow of revenue and expenditures within Illinois is in the 'right' direction, that is resources flow from high income areas to low income areas."

Further, suburbanites tend to pay a much higher percentage of their higher incomes in property taxes than do downstaters. I wince when I shell out $1,100 in annual property taxes for a farmhouse on three acres. "You pay how much?" suburban friends gasp, pointing to their $6,000 and $8,000 bills. "But I live in the sticks," I counter, "where few people want to, or can, live, so my property isn't worth much."

Why has one region sometimes acted in ways that ultimately benefit another region? In the 19th century, southern Illinois helped spur growth in the north because it managed to wrangle some internal improvements for itself. In the 20th century, the creation of the RTA was sealed by a Mayor Daley, who, thinking of his own desperate need of cash for the CTA, helped to save suburban commuter rail in the process. And last year, many of the legislators from the metro-Chicago region who voted for school funding reform that benefited downstate heavily did so because they were ultimately convinced it was the right thing to do.

Illinois' regions have not always been so helpful to one another, of course. For the first half of this century, downstate lawmakers deprived Chicago of representation guaranteed to it by the state's Constitution. (Even before redistricting in 1955, however, when Chicago was underrepresented in the legislature, shrewd, disciplined city pols were able to carve out endless exemptions from state statute for Chicago.)

Poorer school districts have long been denied anything close to parity in resources with rich districts, and still are, even with the 1997 enhancements. (If cost-of-living differences are figured in, however, the disparity narrows. And many of the poorer districts make less local tax effort than do suburbanites, certainly so when figured on the basis of income.)

Still, this review suggests that historically the geo-political regions of Illinois not only need, but have helped one another along the way. And for the future, suburban and Chicago leaders need to think of themselves as part of an organic whole, not as simply different and separate.

There are positive signs. "Chicago assumed for too long that it could go it alone," says Jim Ford, longtime analyst at the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission. "But this mayor and his suburban counterparts have finally figured out they are not natural enemies." Indeed, last year Daley appointed Rita Athas, who formerly worked for a suburban municipal group, as his high-profile liaison with the suburbs. "I'm not sure what will come of it," says Ford, "but something [good] is taking place."

Jim Nowlan is a former legislator, retired professor and political scientist from the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Illinois Issues September 1998 | 27

|