Taking the high road?

It may take the outrage of suburbanites

stalled on the Tri-State

before the wheels

of regionalism really

move in

the Chicago metro area

by Jon Marshall

Illustrations by Ralls Melotte

Some unusual gatherings are occurring around northeastern Illinois these days.

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and dozens of suburban mayors are chatting amiably about what they have in common. A task force of legislators and community leaders is discussing ways to control the region's growth. Cook County Assessor James Houlihan and more than a hundred government officials and civic activists are talking about overhauling the area's tax structure.

Suburban and city leaders sitting down together to discuss metropolitan Chicago's common good - what's going on here? Is this some bizarre side effect of El Niño? Have we left Illinois, where political body slamming between different parts of the state is a favorite sport?

The answer is none of the above. What's really happening is northeastern Illinois' version of the latest national political trend: regionalism. Greater Chicago's head-over-heels expansion has spurred many government, community and business leaders to look at common approaches to such headaches as traffic congestion, pollution, inequitable school funding and vanishing open space.

"The awareness of the problems is greater than ever and a wider variety of people are interested in exploring options," says Joyce O'Keefe, who promotes regional partnerships as associate director of the Openlands Project, a nonprofit environmental group.

But efforts to forge regional partnerships will have to navigate the realities of a political landscape where competition is more common than cooperation. The existing regional bodies have little authority to make substantial changes, and the area's hundreds of local governments are reluctant to give up power. Any regional strategy will have to win the blessings of the state's many competing power centers.

In other words, it isn't going to be easy.

What exactly is regionalism? Instead of tackling issues at the national, state or local levels, it focuses on creating cooperative efforts in metropolitan areas that share common environmental and economic bases. In the Chicago region's case, we're talking about issues facing the 7.6 million people who live in the six-county area of Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry and Will counties. Some analysts include DeKalb, Grundy, Kankakee and Kendall counties, northwest Indiana and southeast Wisconsin.

Regionalism takes many forms nationally. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, a regional council shares a percentage of tax revenues from new developments among nearly 200 municipalities. In Portland, Ore., and its suburbs, a regional government coordinates transportation planning

32 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

and administers an urban growth boundary. And in Maryland, "Smart Growth" laws require that state school, road, water and sewer funds be used to support existing communities rather than new infrastructure on open land.

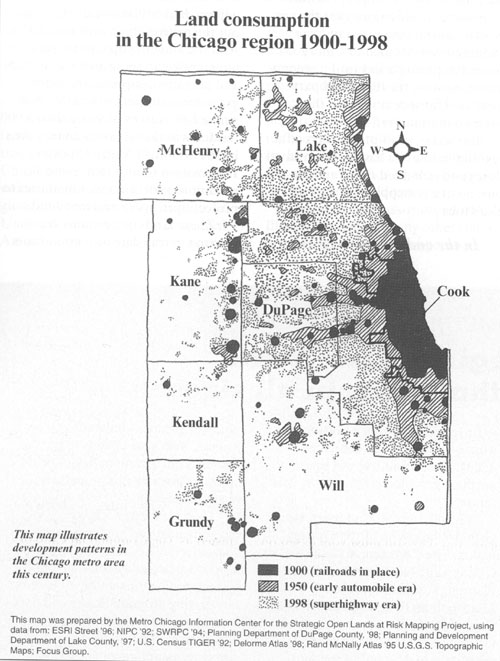

In metropolitan Chicago, the demand for regionalism stems largely from the land-gobbling monster called sprawl. Between 1970 and 1990, the six-county population grew by only 4 percent while the amount of land in urban use spread by more than 33 percent. During that time, more than 450 square miles of open land were converted to residential and commercial uses while Chicago and its inner ring of suburbs lost population, according to the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission (NIPC).

All this outward growth creates tremendous waste, observes Richard Ciccarone, who reviews municipal fiscal health for Van Kampen American Capital Investment Advisory Corp. in Oakbrook Terrace. Ciccarone says taxpayers have to pay for schools, hospitals and sewer lines to serve new neighborhoods when similar infrastructure already exists in older towns. Workers, meanwhile, spend more of their time in traffic as employers move farther out into suburbs lacking mass transit and affordable housing.

When investment moves to newer communities, disparities among different parts of the region widen. For instance, in the northwest suburbs, where growth has boomed, Elk Grove Village and Schaumburg have tax bases of more than $32,000 per resident in equalized assessed value. That's more than four times greater than such communities as Dolton and Markham in the southeast suburbs, where investment has stagnated. This disparity means poorer communities have much smaller tax bases to fund schools, police and other vital services. To avoid this fate, municipalities and counties desperate for property tax revenue compete to lure new malls, office complexes, industrial parks and housing.

Regionalism makes sense in tackling economic disparity, smog, traffic congestion, gangs and other problems that cross municipal and county boundaries. It also makes sense in a global economy where jobs and capital easily cross national boundaries. Nowadays, communities in the Chicago region must compete against Bangkok, Berlin and Buenos Aires rather than against themselves.

But no matter how sensible the idea of improved regional cooperation sounds, the nature of the metropolitan area's politics makes any significant change difficult to achieve. The six-county area has so many power centers with competing interests - Mayor Daley, suburban mayors and village boards, legislative leaders, county board chairmen, congressional bigwigs, business executives - that nobody is really in charge.

The sheer multitude of governments in northeastern Illinois makes it difficult to attain consensus on what the region's strategy should be. The six-county area boasts 287 municipalities, 113 townships, hundreds of school, park and library boards, not to mention countless mosquito abatement, sanitary and other special districts.

What these local governments support depends largely on where they're located. While directing resources to bolster the region's existing infrastructure would please Chicago and such older suburbs as Evanston and Oak Park, it raises the hackles of growing communities on the outskirts of the metropolitan area. People migrate to suburbs like Grayslake, Hoffman Estates, Naperville and Orland Park in search of good schools, safe streets and a nice big yard. Many believe declining communities should fix their own problems rather than asking thriving suburbs to share their tax dollars.

Suburban mayors and village boards balk at the idea of some superregional body usurping their power and controlling the destinies of smaller communities. "I have a real problem telling an edge city what they can and cannot do just because it's in the path of the metropolitan region," says Karen Bushy, Oak Brook's village president and the immediate past president of the DuPage Mayors and Managers Conference.

The region's municipalities often clash over growth issues with their county governments, which control zoning and infrastructure development in unincorporated areas. Although county governments can exert tremendous influence over what goes on within their own borders, none of the county commissioners in the six-county area has become an actor on the broader political stage.

Cook County Board President John Stroger would be the natural leader because he oversees the second most populous county in the nation and a massive judicial and health care system. But most of Cook County is under the control of municipal rather than county government, and Stroger remains overshadowed by Mayor Daley's political influence.

DuPage County, the second most populous county in Illinois, holds many of the region's political cards. It's home to Illinois Senate President James "Pate" Philip of Wood Dale, House Minority Leader Lee Daniels of

33 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

Elmhurst and Attorney General Jim Ryan of Bensenville, a prosperous high tech corridor and a concentrated GOP voting bloc.

Lake County follows close behind. It has the third largest population in the state and the homes of many of the region's CEOs and such other top players as House Deputy Minority Leader Robert Churchill. Lake County, along with north and northwest Cook County, contain some of the region's richest enclaves, and with that wealth comes power. And if Al Salvi of rural Mundelein wins his contest for secretary of state, the patronage power at his command would boost Lake County's influence.

Kane, McHenry and Will don't hold a lot of power yet but are growing so fast they soon will.

That leaves the poorer Cook County suburbs south and west of the city, including Harvey, Hodgkins, Maywood and Robbins, with the least influence. Regional policies to fix up old industrial sites, renovate dilapidated housing and extend public transit would help these suburbs the most. But because they are so busy dealing with day-to-day crises like crime, unemployment and poverty, they have little time left to take on long-term political leadership, observes Wim Wiewel, dean of the University of Illinois at Chicago's college of urban planning and public affairs.

Any major change in regional policy - whether it's revenue sharing, revising the tax system or creating a regional planning body - would have to come from Springfield. The state could accomplish a lot without threatening the power of local governments by using a regional development approach to decide how it spends its money and where it grants permits. Like Maryland's Smart Growth program, Illinois' government could emphasize improving roads, schools, water lines and sewers in existing communities rather than funding new infrastructure on previously undeveloped land.

But a suburban-dominated General Assembly makes such a program unlikely in the immediate future. Philip and House Speaker Michael Madigan, a Chicago Democrat, have a virtual veto in the legislature because they can bury bills they don't like in committees they control. "If Mike Madigan and Pate Philip can agree on something, then it can happen," says Woods Bowman, a professor at DePaul University and a member of the Illinois House from 1977 to 1990.

Philip is known for protecting the interests of his caucus, which is dominated by the suburbs. He says legislators are increasingly aware that their communities share common problems, but they still must vote based on the desires of their constituents. In DuPage County, for instance, voters want their motor fuel tax dollars spent on improving their own roads, not on projects in other parts of the region, he says. "Come here [to DuPage County] between 4 p.m. and 5 p.m. and tell me we shouldn't build another road."

Although Madigan hails from Chicago, his razor-thin majority in the House means he must keep suburban legislators happy. An icy relationship between Daley and Madigan, who doubles as state Democratic chairman, tends to divide the

Democratic caucus and render it less able to act on a regional basis. If Madigan loses his majority in the November elections, the Republicans under Lee Daniels are even more likely to cater to suburban interests.

A stronger push for regionalism, however, could come next year when a new governor replaces Jim Edgar, who has remained relatively quiet on the subject of controlling growth. Democratic nominee Glenn Poshard has said if elected he will create a smart growth commission representing all parts of the state to be chaired out of the governor's office. GOP candidate George Ryan promises to appoint someone in his administration to coordinate development policy and direct state agencies to work together toward managing growth.

Other people could play important behind-the-scenes roles encouraging regional partnerships. Suburban Rosemont Mayor Donald Stephens, for instance, has accumulated power by virtue of his city's economic might and his generous campaign contributions to leaders in both parties. The top executives at major banks, utilities and other businesses can also make things happen. When the legislature granted tax cuts last session, it was the business community that quietly maneuvered to get the lion's share. "They get the ear of anyone they want and generally get what they want," says Gary Mack, a public affairs and media consultant who used to run Edgar's Chicago press office. Their influence will be tested as The Commercial Club of Chicago, the most prominent business group, prepares a campaign to promote more regional cooperation.

Such cooperation becomes especially tricky when tough political decisions must be made about where money is spent and who controls it. Regionalism's real test will occur over such messy questions as whether to allow more casino gambling, extend the North-South Tollway or Route 53, or change the tax system to make school funding fairer.

Nowhere is the stalemate among regional power centers clearer than over the question of whether to build a new airport in the south suburbs. Nearly all political players agree the region will need more airport capacity to keep its economy humming into the next century, but they disagree bitterly over where that capacity should go. Daley, many northwest suburban business and political leaders, and United and American Airlines (with

34 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

the backing of much of the downtown business community) argue that O'Hare International Airport can continue to meet the growing demand.

The push for more flights at O'Hare is opposed by nearby mayors and the area's most powerful congressman, Republican Henry Hyde of Bensenville. They are working with business and political leaders in the south suburbs, including U.S. Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr., a Chicago Democrat, to promote a new airport near Peotone. To get a new airport off the ground, Philip, Madigan, the next governor, the region's congressional delegation and the White House would all have to agree. Small wonder the airport question is no closer to being resolved than it was a decade ago.

One reason such deadlocks occur is that none of the existing regional agencies have any real teeth. As the region's official planning organization, the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission makes forecasts and recommendations on issues ranging from flood control to smog reduction. The Chicago Area Transportation Study (CATS) is responsible for long-term highway and mass transit planning. But neither NIPC nor CATS has the budget or authority to make things happen on their own.

Examples of successful partnerships, however, do exist. The Regional Transportation Authority coordinates mass-transit spending throughout the six counties. The Openlands Project, NIPC and dozens of local jurisdictions are working on a Greenways Plan to link 1,700 miles of bike and pedestrian trails throughout northeastern Illinois. For the past two years, a similar coalition of government and private groups has worked on the Chicago Wilderness campaign to restore the region's natural areas.

But the best examples of cooperation appear at the subregional level. Councils of government, such as the Northwest Municipal Conference and South Suburban Mayors and Managers Association, have gained power in recent years by cementing ties among local governments. Municipalities now cooperate on waste disposal, water supplies and a host of other needs. For instance, after the General Assembly voted to deregulate electricity, the councils of government crafted a model law used by more than 150 municipalities so each would not have to develop an ordinance from scratch.

In this way, councils of governments are acting as building blocks to greater cooperation across the region. In Cook County the councils are participating in Assessor Houlihan's review of the tax system, and mayoral groups from all six counties are sending representatives to the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus formed by Daley.

In the past, Daley had a strained relationship with the suburbs over such issues as affordable housing, economic development and O'Hare noise. But last year he began paying more attention to the suburbs by forming the mayors' caucus and hiring Rita Athas, the former executive director of the Northwest Municipal Conference, as a special assistant. Since the caucus began last December, the mayors have held three meetings and plan to get together quarterly to discuss such issues as complying with EPA air standards, ending traffic bottlenecks and preventing ComEd blackouts. "We're finding there's a lot more that unites us than divides us," Daley says.

Some other scattered seeds of regionalism are sprouting in Springfield.

35 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

Last spring, the General Assembly approved $500,000 to help NIPC draft a regional growth strategy, the most help it has given the planning agency for at least a decade. The House, meanwhile, created a Smart Growth Task Force to study how state transportation, land use and budget policies are contributing to the loss of farmland and open space.

The area's congressional delegation has also been promoting regional cooperation on individual projects. For example, U.S. Rep. John Porter, a Wilmette Republican, used his influence on the House Appropriations Committee to win money for the new North Central commuter rail line running from Antioch to Chicago, a project requiring cooperation among municipalities, the Illinois Department of Transportation and the Metra commuter rail service.

But so far, most of the successful regional initiatives have come in small doses and remained rather innocuous; no one is stepping on anyone else's toes.

In the end, the power centers will back a more aggressive regional approach only if residents throughout the metropolitan area demand it. And the longer people sit in traffic jams, choke on smog and watch fields and pastures disappear, the more grass-roots

36 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

support will build. Witness a 1997 survey of more than 3,000 residents in the six collar county area by the nonprofit Metro Chicago Information Center that found 71 percent support zoning boundaries to protect open space and farmland.

These kinds of opinions are starting to translate into grass-roots activity. The Center for Neighborhood Technology and the Metropolitan Alliance of Congregations, for instance, are building alliances between suburban and city community groups to tackle such issues as affordable housing and mass transit.

Another powerful voice is coming from United Power for Action & Justice, formed by the Archdiocese of Chicago, the state's three largest labor unions and more than 250 other religious and community organizations. United Power is using the Industrial Areas Foundation, started by famed community organizer Saul Alinsky, to train activists and conduct an outreach campaign in the city and suburbs. They are succeeding in drawing attention: Last fall about 10,000 people attended the group's first rally in Chicago. Thus far, United Power has not promoted any specific solutions to the region's problems, but its leaders have mentioned education funding, crime and affordable housing as issues they may address.

Despite such grass-roots efforts, Illinois lags behind many other states in promoting regional cooperation. But then again, other states don't have political divisions quite like Illinois. As a result, backers of regionalism may have to settle for small victories before they can expect dramatic changes.

"In Springfield they say if you can't get a dinner, take a sandwich," Woods Bowman says. "Maybe we have to inch our way into the grander plan."

Jon Marshall writes about social, political and economic issues. His last article for Illinois Issues, "No Free Ride," appeared in the May issue.

37 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

SOMETHING TO SNEEZE AT?

'Regionalism' floats

plans that come in all sizes

"Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood."

Daniel Hudson Burnham, 1846-1912

In 1909 famed architect Daniel Burnham and colleague Edward Bennett introduced The Plan of Chicago, a grand scheme that shaped the city through much of the 20th century. The Burnham Plan envisioned much of what has made Chicago great: beautiful lakefront parks, boulevards to carry traffic between the city and suburbs, a bounty of neighborhood parks and an organized system of railroad tracks and terminals.

Nearly 90 years later, some of the region's mightiest movers and shakers, academic thinkers and community organizers are drafting big plans of their own. Their agendas include some of metropolitan Chicago's biggest issues: education funding, crime, taxes, transportation, economic development and land use. Running through them all is one common theme: promoting more regional cooperation.

Whether these plans have the power to stir anyone's blood remains to be seen. But if even a portion of what's being considered becomes reality, these initiatives will shape northeastern Illinois far into the 21st century.

The players involved comprise a virtual Who's Who of the Chicago region. The Commercial Club of Chicago, the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission, the Metropolitan Planning Council, the Cook County Assessor's office and Governors State University are among those developing regional campaigns and plans.

"There are a lot of people of tremendous goodwill who want to see things happen regionally," says attorney Elmer Johnson, director of The Commercial Club's Metropolis Project. "We haven't seen anything like this since the days of Burnham."

One of the most ambitious is Johnson's project. Two years ago The Commercial Club - which boasts some of the top CEOs and civic kingpins in Chicago - created committees to draft reports on the region's transportation, taxation, education, governance, economic development, land use and housing. This spring the club asked for feedback on its findings from other political, business, religious and civic leaders. Next year it plans to publish the results in a hardback book and create a committee to promote its recommendations.

The Commercial Club's recommendations are likely to stir controversy. They may encourage the legislature to change the state's tax system, Johnson says, and promote a tax-sharing program that would create a regional agency. This approach could decrease the competition among municipalities, develop a fairer way to fund schools and give incentives to counties and municipalities that fix up blighted areas and discourage leapfrog development.

Another regional plan is brewing at the governmental level. Last fall the Northeastern Illinois Planning Commission - the state planning agency for Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake, McHenry and Will counties - embarked on a three-year project to create a regional growth strategy. A NIPC committee is preparing recommendations to guide the region's growth in ways that encourage investment in existing communities.

Last year NIPC also joined the

36 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

Metropolitan Planning Council, a nonprofit group of business, professional and planning leaders, to launch the Campaign for Sensible Growth. The campaign's partners include the Regional Transportation Authority, Openlands Project, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Business and Professional People in the Public Interest, the American Lung Association of Metropolitan Chicago and the Urban Land Institute.

"Groups like these understand how their issues are linked with the broader regional context," says MarySue Barrett, the Metropolitan Planning Council's president. The campaign's goals are to identify and pursue sensible growth policies for the metropolitan area. Its members plan to advocate for policy changes, provide technical assistance to communities and teach the public about the advantages of balancing economic growth with environmental quality.

In June, Cook County Assessor James Houlihan convened his own forum to discuss reforming the local and state tax systems. The forum has more than 250 members, including representatives from the Suburban Mayors Action Coalition, the Civic Federation, the Taxpayers' Federation of Illinois and local chambers of commerce. Three task forces are now studying the tax system and its impact on development. By next spring, Houlihan hopes to have a report with recommendations ready for the Illinois General Assembly and the Cook County Board.

The area's universities are also getting into the act. In 1994 Governors State University in University Park and the South Suburban Mayors and Managers Association developed the Regional Action Project/2000+ for the southern suburbs. RAP/2000+ has held town meetings and created action teams to address such regional issues as education, economic diversity and environmental protection. It also sponsors LincolnNet to help people and institutions share ideas and information through computer and telephone access. Two years ago Governors State created the South Metropolitan Regional Leadership Center to carry on the RAP/2000+ process and continue developing new regional initiatives.

Foundation money is fueling much of this recent focus on regionalism. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, for example, is funneling roughly $2 million a year to projects geared toward regionalism, including the work of the Metropolis Project, Governors State, Metropolitan Planning Council and Houlihan's tax forum. In May, the MacArthur Foundation and the Chicago Community Trust co-sponsored a three-day retreat in Wisconsin, where political leaders and members of The Commercial Club reviewed the preliminary findings of the Metropolis Project.

The danger remains, of course, that all of the groups working on regional initiatives will issue reports and plans that end up sitting on shelves collecting dust for the next generation to sneeze at. "Indeed, Chicago is legendary for producing ambitious plans that are never implemented," write Graham Grady and Pamela Freese in Toward a Regional Plan of Chicago: Shaping a Burnham 2000 Initiative, a 1996 study for DePaul University's Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development. The solution, Grady and Freese suggest, is for the groups to come together to develop a single regional plan. They propose the creation of an advisory board of regional leaders to steer this mega-plan's creation.

Plenty of cross-pollination, however, already exists among the different efforts. For instance, Paula Wolff, the president of Governors State, co-chairs one of the Campaign for Sensible Growth's committees and serves on one of the Metropolis Project's subcommittees. "A lot of the groups that had previously worked in isolation," she observes, "are now working together."

Jon Marshall writes about social, political and economic issues. His last article for Illinois Issues, "No Free Ride," appeared in the May issue.

37 | September 1998 Illinois Issues

|