CONVERSATION WITH THE PUBLISHER

Spinning gun, burned-out van

define low points of campaigns

by Ed Wojcicki

A group of Northwestern University

students watched a selection of

television commercials from this fall's

Illinois political campaigns. Showing

them the ads were Gordon Walek

and Cynthia Canary of the Illinois

Campaign for Political Reform, which

conducted an Ad Watch during the

last six weeks of the campaign. Asked

which ads stood out most, the students

identified two from the gubernatorial

campaign.

One depicted Democrat Glenn

Poshard as an extremist on guns. It was

one of Republican George Ryan's

earliest TV spots, showing a closeup of a

pistol turning slowly on the screen until

it pointed directly at the viewer. It also

included images of ghostly gang members running as if ready to do harm.

Ryan's message was clear: Poshard

would allow dangerous people to carry

guns freely all over Illinois; and, since

the ad elicited fear, Poshard must be a

frightening candidate.

The other ad, sponsored by the state's

Democratic Party, showed a burned-out

minivan in which six children had died

after a truck accident. The ad linked that

accident to a scandal involving the

issuance of commercial driver's licenses

by the secretary of state's office, thereby

suggesting that Ryan was responsible for

the death of those children.

The spinning gun and burned minivan are the two most lasting images from

this year's campaign. Asked for whom they would vote based on those ads, the

Northwestern students said they would

not vote at all, Canary related. Instead,

the students asked rhetorically why

they should vote for someone who wants

everyone to have a gun, or for his

opponent, who kills kids.

The sad truth is that these ads

probably served their purpose, because

campaigns design negative ads to stop

citizens from voting for someone they

might have considered, or to stop them

from voting at all. Nasty campaign

messages are targeted mostly toward

that 20 percent to 30 percent of voters

who are independent, undecided or

"persuadable." Studies by Stephen

Ansolabehere and colleagues at UCLA

in the mid-1990s confirm the conclusion

that negative ads reduce voter turnout.

They extensively analyzed several California races and then 34 other campaigns around the country, and found

strong correlations between negative ads

and lower turnout. "In short," they said,

"exposure to campaign attacks makes

voters disenchanted with the business of

politics as usual," and the result is that

the class of nonvoters is on the increase.

A strategy for winning has come to

this: making one's opponent the focus of

the campaign and defining that opponent negatively. That is what Ryan did to

Poshard, first with the spinning gun ad

in the summer and then with additional

messages both on television and in print.

These messages painted Poshard as

Illinois Issues December 1998 / 3

extreme — extremely dangerous — on

issues that people care about, such as

guns and the environment. Ryan also

ran ads in Spanish-language newspapers

in Chicago, using the tag line, "Poshard

is not the Democrat you think he is,"

Northwestern's Medill News Service

reported. Ryan used quotes from prominent Latino Democrats who criticized

Poshard, but these ads did not reveal

that the quotes were from the primary

election season, when the Latinos

supported John Schmidt over Poshard.

Poshard never recovered from the

initial image that he, like the gangsters on television, is a scary man. Paul

Kleppner, a longtime political observer

at Northern Illinois University, said he

had gathered anecdotal information

before the election that some Democratic voters in the liberal Lake Shore wards

planned not to vote in the governor's

race because they formed impressions

from ads in the primary and general

elections that Poshard was too conservative on issues such as guns, gay rights

and abortion. An early analysis of

numbers shows that Kleppner was right.

In the lakefront wards where Democrat

Carol Moseley-Braun whipped Republican Peter Fitzgerald by 32, 000 votes in

the U.S. Senate race, Poshard trailed

Ryan by 6, 600 votes, the Chicago

Tribune reported.

Much ado was made just after the

election that voter turnout was "higher

than expected.'? But a closer analysis

shows that the Election Day glee can be

attributed simply to pundit predictions

about low turnout. In fact, the statewide

turnout was less than 55 percent,

according to Ron Michaelson, executive

director of the State Board of Elections.

The 1998 turnout is about the same as

the last two gubernatorial elections: 53

percent in 1994 and 57 percent in 1990,

both sharply lower than the 65 percent

turnout in 1986. So this could hardly be

considered a high turnout.

A major problem with nasty, unfair,

untruthful political messages is

that they can leave voters confused and

uninformed about where the candidates

actually stand. Kleppner explains

studies show that voters who feel cognitively "cross-pressured" often do not resolve the conflict caused by the

messages, and they drop out of the

process, shrinking the size of the electorate. Candidates run distorted ads to

create cognitive conflict, especially

among voters who are undecided but

might be leaning toward one candidate

or another. Voters with a strong disposition in favor of one candidate are

likely to dismiss the negative messages,

Kleppner says. The ICPR's Canary

agrees with Kleppner's assessment that

the purpose of attacks is to get people

"to become so disenchanted that they

stay home."

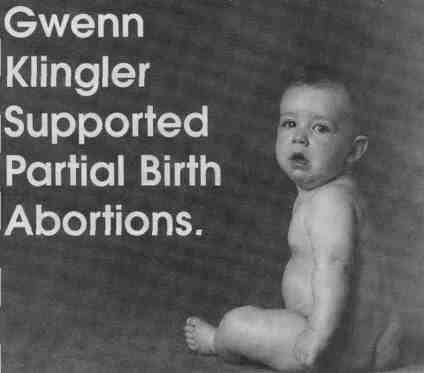

The Democratic Party of Illinois paid for a controversial four-page flier with this

eye-catching cover and sent it to many homes in Republican state Rep. Gwenn

Klingler's Springfield district on behalf of her Democratic challenger. Klinglev

was upset because the flier did not explain her concerns about the unconstitutional

provisions of one of the hills, and because she opposes "partial-birth" abortions

unless there is a serious threat to the mother's health. Some Democrats were

angry that their party paid for this mailer because Klingler is pro-choice, their

party's plat form is pro-choice, but the flier had a anti-abortion tone to it.

But not everyone believes the cause-

and-effect is that clear. Fred Yang, who

works for the Garin-Hart-Yang

research group in Washington, D.C.,

and did polling for U.S. Sen. Richard

Durbin two years ago, is not as certain

that candidates and consultants deliberately attempt to reduce voter turnout

by running negative ads. Nonetheless, Yang concedes, two facts are clear:

Voter turnout is low, and there are a lot

of negative television commercials. He

says consultants advise candidates to

go negative because it is easier to get

the attention of undecided voters, the

"persuadables," with negative messages

than with positive ones. The electorate

is increasingly turned off to politics,

and political campaigns are less

important to people than hamburgers

or deodorant, Yang says. So the

purpose of negative ads is to get

potential voters' attention and

persuade them, if they vote at all, to

vote against somebody. But "it's hard

to get their attention," he says.

So whether candidates and consultants deliberately set out to depress

voter turnout, or use hard-hitting

messages just to get voters' attention,

the effect is the same: Voter turnout

suffers, and voters are getting more

cynical. Overall, negative campaigns

4 / December 1998 Illinois Issues

reduce voters' confidence in our democratic form of government. A democracy with citizens as nonparticipants is

troubling. "Exposure to negative

advertising increases voters' cynicism

about the electoral process and their

ability to exert meaningful political

influence," Ansolabehere wrote in a

1995 book, Going Negative: How

Attack Ads Shrink and Polarize the

Electorate.

The most troubling question of

all is whether candidates could ever be

persuaded to stop distorting opponents' positions and engage instead in

a more serious, civil and detailed

debate about policy and character

issues affecting voters' lives, not just

their fears. As long as they're convinced that going negative is part of

the formula for winning, it seems

unlikely they will change.

But two responses from an outraged

public might help. One would be a

more comprehensive statewide Ad

Watch effort. A media outlet or other

organization could analyze ads not

only for accuracy, but also for fairness

in tone, images, sound and color. Some

of this happens now, but mainly by the

largest newspapers and in a spotty

fashion. In an Ad Watch, the "tone"

issue is vital, because the context and

the tone can send a powerful, distorted

message even if the facts presented are

difficult to dispute. A new book from

the University of Illinois Press, Video

Rhetorics, points out that in commercials, the pictures and sound are more

powerful than the spoken word. So

viewers will remember the image of a

spinning gun and burned-out van far

longer than they will recall the narration in the ads. My second recommendation would be for the state to

arrange the publishing of a series of

official voters' guides and send a

regional version to every voter's home.

That guide would give statewide and

legislative candidates one page to

provide basic facts about themselves,

their backgrounds, their qualifications

and their positions. Voters might learn

to rely on this guide as a place to get

straightforward information and

reduce the confusion they feel after

being barraged by all of the other

political messages.

While negative campaigns clearly

cause confusion and outrage

among the electorate, some additional

observations about the nature of political communication are important:

• The first is that negative campaigning is not a recent phenomenon.

Former Gov. James Thompson told the

Civic Federation in Chicago earlier this

year that American politics have

always been "raw, cruel and personal."

Indeed, they have. Several recent books

have documented gross mudslinging in

the earliest days of American history,

and even into European history and

the time of Cicero.

• A second observation is that

direct-mail printed fliers are also a requisite part of the media mix in Illinois

campaigns, especially in targeted legislative races. In southern Illinois, for

example. Democrat Don Strom of Carbondale ran an aggressive campaign

against first-term state Rep. Mike Bost.

But a flier on Bost's behalf blared:

"BEWARE! The Chicago Political

Machine is moving south to influence

your vote." The flier, with a picture of

the Chicago skyline on the cover,

opined that Strom would be controlled

in Springfield by House Speaker

Michael Madigan of Chicago. Downstate, such anti-Chicago messages

often play well. And negative printed

pieces flood the mailboxes and porches

of voters in the final weeks of every

campaign in a carefully orchestrated

fashion.

• The third is that in an era when

media-dominated campaigns have for

the most part replaced party-dominated efforts — Peter Fitzgerald's successful campaign for the Senate being the

most striking example this year — personal contact remains effective in turning out voters. Studies document that

the best way to get voters to the polls in

spite of negative commercial messages

is for candidates or their campaigns to

have personal contact with potential

voters. So the "higher than expected"

turnout this year in some places can be

attributed to grass-roots efforts among

African Americans in Chicago and

other get-out-the-vote efforts.

• The fourth is that any rational

analysis of political messages must not

condemn everything that is commonly called "negative" in campaigns. Labeling everything as "negative" — which

the media and voters tend to do —

ignores important distinctions between

factual differences of opinion and

unfair distortions or lies. William G.

Mayer makes a compelling argument

defending some forms of negative campaigning in the fall 1996 issue of Political Science Quarterly. He says any

candidate who argues for major

changes in government policies must

show that current policies are not

working. "Negative campaigning

provides voters with a lot of valuable

information that they definitely need to

have when deciding how to cast their

ballots," he writes. "The need for such

proposals becomes clear only when a

candidate puts them in the context of

present problems — only, that is to say,

when a candidate 'goes negative.'" He

then laments that most academic and

popular writing "criticizes all negative

campaigning, without any attempt to

draw distinctions about its truth, relevance, or civility. ... If the problem

really is with campaign ads that are

misleading or irrelevant or nasty, why

not just say so?"

OK, I'm saying so. Too much of

what we saw and heard in the past few

months was misleading, nasty or irrelevant. Evidence exists that the offensive

political rhetoric confuses voters and

does real damage to opponents' campaigns. In short, the ads work. Honorable candidates get trashed, forcing

them to respond with additional

smears. The ugly spiral heads downward, leaving many voters at home,

leaving the electorate more cynical, and

leaving many talented citizens wondering why they would ever want to get

involved in such a disgusting process.

A word of thanks for helping gather

campaign material for this column goes

to our readers who sent information to

me; to Jennifer Riddle, a graduate

student at Southern Illinois University

at Carbondale: to students of Illinois

Issues columnist Jim Ylisela at the

Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University; to Protestants for

the Common Good; and to the Illinois

Campaign for Political Reform.

Illinois Issues December 1998