Essay

Under the radar

The Unfunded Arts are flourishing in central Illinois.

What are we to make of these anonymous artists and their work?

by Dan Guillory

Photographs by Randy Squires

Tunneling down the furrow of Illinois 128 in end-of-September

weather, accelerating between walls of

high corn and simmering waves of

light, I detect a little black glitch in my

peripheral vision. Some strange shape

flies into the ambient brightness then

instantly vanishes.

Route 128 points like an arrow to

Shelbyville, the county seat of Shelby

County. And on subsequent and better

charted trips down the two-lane blacktop, I positively identify the UFO as a

black plywood silhouette of a crow,

realistically perched on a single section

of white picket fence artfully wedged

into the glowing wall of corn. A farmhouse stands in the background, and I

immediately sense the deliberately

staged quality of the scene, a rural

tableau replete with rusty-hooped wagon wheel, imitation (two-dimensional)

birdhouses in various pastels, and

plentiful clumps of Spanish moss

curled and draped into frames.

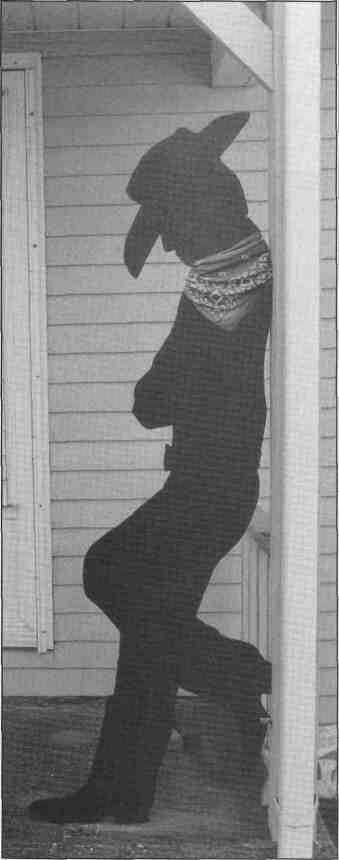

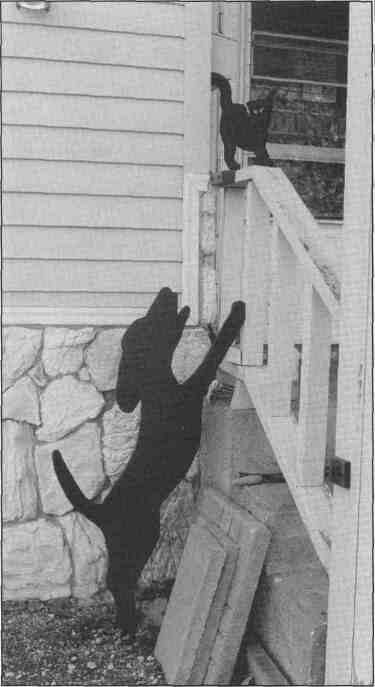

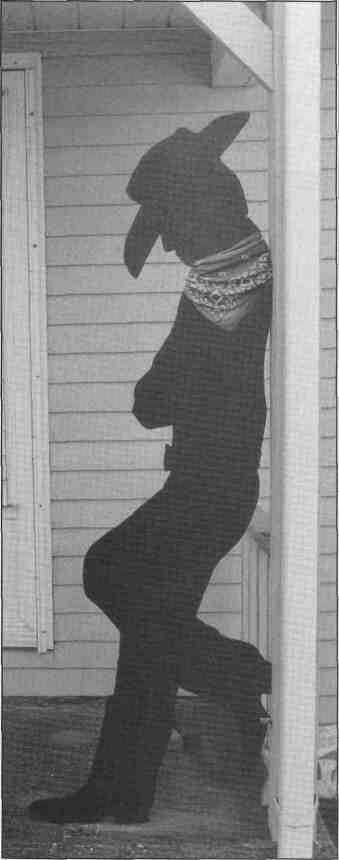

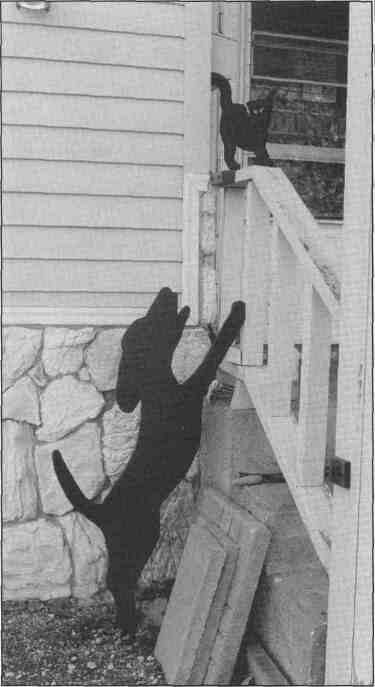

The crow, I later realize, is a subspecies of a larger population of matte-painted silhouettes: the Dobermans

reared up on hind legs and caught in a

permanent fighting stance outside

Hillsboro on Route 16, the turn-of-

the-century farmer and wife (with real

bandannas) waving goodbye to Illinois

motorists as they cross over into Indiana on Interstate 74, the conductor

and old-fashioned locomotive riding

the roof of Stan's Restaurant in Findlay, the flying Canada geese flapping

their black wings on the walls of Wooter's Sport Shop on the nearby

Bruce Road.

Even my closest neighbor, Arliss

(not his real name but close enough),

has positioned a silhouette of a young

girl with watering can at the edge of

his bean and tomato garden. Whenever 1 behold her, I do the proverbial

Double Take. For these outlined figures are performing a kind of prairie

version of M.C. Escher's trompe 1'oeil

deception, exciting the edges of the

cerebral cortex where the meaning of

meaning resides.

Silhouette art has dislocated my

thinking, making me conscious of the

fact that what I "see" of the world

(including people and ideas) is often a

two-dimensional artifice. I am, in fact,

studded with more silhouettes than

any portion of the landscape — an

insight both disturbing and oddly

liberating. But isn't that the point of

art — to liberate us and explicate our

private spaces? I was being forced to

reconstruct my all-too-solid prairie as

a mere panorama of subtle cutouts on

an endlessly pink horizon of steeples,

barns, windmills and willow trees.

Here were these anonymous artists

improbably turning the hybridized

world of agricultural Illinois into the

stuff of art. Somehow they had made

the leap from thinking of the museum

as a metaphor for the world to redefining the world as a museum. They

became the self-appointed and unpaid

curators of this big airy space,

installing free-standing artwork on the most visible roadsides and ridges. In a

commercialized culture where we

mount glitzy shows of Monet and Van

Gogh, turning "high art" into mega-

media events (TV documentaries and

"specials") and marketing opportunities (Monet's water lilies into postcards, Van Gogh's starry night into a

tote bag), art has become a very serious business. These silhouette-makers,

throwbacks to the creators of portrait

silhouettes and paper cutouts of the

18th and 19th centuries, remind us

that, at some irreducible level, art must

always be fun.

Now I am not suggesting that plywood figures (including Holstein lawn

cows and mushrooms), painted saws,

spray-painted willow wreaths,

two-dimensional birdhouses, tin

Christmas figures (Santa, the Elves

and Frosty), "antiqued" spice racks,

various Cute Things (ice skates fashioned from pipe-cleaners and paper

clips, snowmen created by cleverly

stacking smaller and smaller inverted

flower pots atop each other after daubing them white) will supplant Da Vinci

or Degas. And I freely concede that it

is sometimes powerfully frustrating to

distinguish outright Trash (broken

buttons and old ballpoint pens) from

so-called Collectibles (old soda bottles,

bits of barbed wire and matchbook

covers); Kitsch (Lincoln ashtrays and

busts, usually in the form of obscenely

bronzed-over pot metal) from Popular

Art (old movie posters. Star Trek

lunch boxes, Coca Cola signs and Mr.

32 / December 1998 Illinois Issues

| Peanut lapel pins).

It is even harder to draw the line

between Folk Art and the unrecognized and largely Unfunded Art of

which I speak. Most computer-literate

citizens in the 1990s (a handy demographic grouping) would probably

consider a Shaker table art, and they

might stretch their definition a wee bit

to include, say, a Mennonite rocker or

an Amish quilt. Folk art is generally

acceptable nowadays because it is

encoded as "high craft" (especially if it

takes the form of textiles, glassware or

ceramics) as opposed to the "low

craft" randomly scattered on tabletops

at yard sales, auctions, church bazaars,

cake sales and the like.

Yet unfunded ("low") crafts of all

kinds are being created at an exponentially growing rate all over the country.

They are generally unheralded and

unnoticed by the arts press, omitted by

Dan Rather and company from the

evening news, and dumped into the

same informational black hole (the

quasar site for unwanted data) that

contains the ubiquitous little theater

groups, low-circulation literary magazines, and independent creative writing

collectives and support-groups.

No reliable census of these arts and

crafts practitioners even exists; they

survive and even thrive below the

sweeping radar line of the art world's

official screen, meriting not so much as

a blip — or a dollar — when reckoning

time arrives, whether in the form of

grant money, documentaries or col-

|

|

Illinois Issues December 1998 / 33

|

|

umn-inches of critical prose.

By any reasonable definition of art,

however, indigenous Illinois crafts

deserve more than passing attention.

Even painted silhouettes in the favored

plywood medium and saw blades

painted with latex trim paint possess

style; that is, they can be readily replicated with numerous variations on a

basic theme. Furthermore, they

attempt to accomplish difficult aesthetic goals with unforgiving or

unyielding materials (as poets in the

act of rhyming, or potters in the

process of squeezing slimy clay cylinders into vases, pots and jugs).

But no matter how carefully we

frame the discourse on art or arts

funding, it is never easy to categorize

the encyclopedic variety of art being

produced today. So it is entirely understandable — if regrettable — that a

state regranting agency like the Illinois

Arts Council would be forced to draw

sharp lines of demarcation between

fundable and nonfundable forms of

craft.

Utopias, by definition, are impossible to find. Not every artist can (or

should) be funded, but it behooves us

to rethink our understanding of art

and the surprising role it continues to

play in the background and foreground of our daily lives.

This closer scrutiny of arts funding

is all the more appropriate when taxpayer revenue is involved (including

appropriations from the Illinois state

legislature and grants direct or indirect

from the National Endowment for the

Arts). And the difficulties of clear discourse go well beyond the old frustrating conundrum of how to define art or

how to square the aesthetic standards

of high (or elitist) art with the pressing

needs of a democratic society (especially in its present highly diverse and

multicultural form). There are even

deeper, more intractable, confusions

that grow out of misunderstandings or

misreadings of the powerful effects of

class and technology.

While trying to untangle these

knotty ambiguities and nagging inconsistencies, I am drawn to a "crafts

barn" (actually a converted elementary

school building) in nearby Moultrie

County. The structure has recently

|

34 / December 1998 Illinois Issues

been repainted and tuck-pointed. New

windows gleam, colorful canvas

awnings puff out like sails, and the

whole place is a perfect example of

"adaptive re-use," a prime tenet of the

new architectural credo. There is an

Amish kitchen on the premises

(Arthur, the heart of Amish country, is

only a few miles distant), with whitecapped matrons doling out hefty portions of homemade noodles, braised

pork chops, green salad with sweet and

sour dressing, blackberry cobbler and

strong coffee. I shall leave those culinary arts to another commentator,

however, and pull myself away to focus

instead on the ancient schoolrooms

turned into showplaces for antique

reproductions, Amish tables, scented

candles, "antique" greeting cards in

favored tones of sepia and sienna, and

abundant local crafts, including odd

sign boards with a single leaf or flower

captioned Thyme or Sweet William.

Having spent the last few days (and

weeks) brooding on the themes of

Class and Technology, I amble over to

the display of painted saw blades and

stand dumbly before a particularly

interesting example. It is a cross-cutting saw about five feet long with

raised walnut handles, perhaps 80 or

90 years old (maybe older) — the kind

of tool a father and son might have

used to saw chunks of pond ice or river

ice into neat blocks for stacking and

storage in the icehouse. Those clear

and unpolluted blocks were stored for

later use, making possible the sweet

summery pleasures of hand-cranked

ice cream and oversized tumblers of

lemonade, all the more enjoyable in the

days before air-conditioning or even

electric fans.

Already, I am starting to register the

implications of Class and Technology

in this artifact now become a salable

piece of art. This painted saw was once

a working tool put to daily use,

anchored to a particular niche in

history, and still an authentic symbol

of the working class. I am no Marxist,

but clearly the artist is implying something by choosing to use a tool in this

way — a rather special twist on the

meaning of "adaptive re-use."

The saw testifies eloquently for the

Old Ways (pre-electric and, more important, pre-electronic); it is old

technology given new life. In a world

of high-tech surfing on the Net, this

rusty old gap-toothed thing persists in

all its low-tech glory. Its original owner

was some yeoman farmer, most likely,

a weathered fellow with callused hands

and dirty nails. There isn't anything

obvious to suggest Baby Boomer or

Yuppie values in this odd old implement, yet it exerts a powerful attraction on these very groups, apparently

meeting needs not fulfilled by the

ergonomically correct world in which

they try to unwind.

The saw has been painted in four

seasonal panels, beginning on the left

with botanically correct redbud trees

bursting into magenta flowers, and

ending on the right with a refrigerator-white winter scene of Zen-like stillness.

In between one sees depictions of

plowing, harvesting, haying — in

short, the agricultural world of hard

manual labor, performed out of doors,

the world most familiar to Americans

until the decade after World War I

when farmers, by the millions, took to

their Tin Lizzies and headed for the

Big City.

In a flash, I saw the black plywood

silhouettes as the ghostly survivors of

this idealized world. They could live

with two-dimensionality in the form of

scenery on saw blades and unusable

birdhouses because everything in their

world was purely symbolic, after all.

They had once possessed the Platonically perfect homestead that we moderns deconstructed about the time

phrases like "quality time" and

"latchkey children" appeared on the

scene.

We became profoundly and genuinely nostalgic, a word that derives from

the Greek nostos or "homecoming."

And the only homecoming available

was through art. This variety of nostalgia was existential in origin, and

hence it could not be satisfied by the

instant nostalgia offered by made-for-

TV movies or superficial documentaries of sports figures, movie stars

and the like. So no one had to inform

the unfunded artists that there would

be authentic interest in their work;

they already knew that in their bones.

In a flash, I saw the black

plywood silhouettes as

the ghostly survivors of

this idealized world.

They could live with the

two-dimensionality in the

form of scenery on saw

blades and unusable

birdhouses because everything

in their world was purely

symbolic, after all.

In this Postmodern Era, academics, politicians and social reformers have

opened the cultural doors to all

comers, while innumerable people have

devised some ways to "come out" of

whatever closet restricted their lives

(marriage, occupation, sexual orientation). So can't the art establishment, in

this spirit of openness and inclusion,

offer an official entree to our local and

independent artists, those low fliers

coming in, even now, just below the

radar?

Dan Guillory, an English professor at

Millikin University in Decatur, is a former

member of the Literature Arts Panel of the

Illinois Arts Council. He is a contributor to

Illinois Issues and the author of Living with

Lincoln: Life and Art in the Heartland,

The Alligator Inventions and When the

Waters Recede. He is also the author of the

Introduction to the new University of Illinois Press edition of Madeline Smith's

Lemon Jelly Cake.

Illinois Issues December 1998 / 35