|

C U R R I C U L U M M A T E R I A L S

|

Colleen McElroy

Overview

Main Ideas

|

The Polish Partitions devastated the Polish state, ending the rich multicultural character of that commonwealth. In the process, the Partitions contributed to a deep ethnocentrism that emigres carried over to New World settlements. The largest of these Polish immigrant settlements evolved in Chicago. Here Polish Catholics developed a community-parish system that became a model for later settlements. Because of the heavy social, economic, cultural, and religious investment in their national parishes in Chicago, Poles tended to resist movements of other population groups into their neighborhoods. The overwhelmingly Polish and Catholic characteristics of these national parishes discouraged multicultural contacts with other ethnic, religious, and racial groups. The American Catholic hierarchy hoped to breakdown these ethnocentric tendencies by utilizing the territorial parish model. But in 1920 Chicago these assimilation efforts were fiercely resisted by Poles. Poland's historic multicultural character — in Europe and America — was by this time abandoned.

Connection with the Curriculum

This material is appropriate for the introduction of multiculturalism into history, social studies, government, and humanities classes.

Teaching Level

Grades 9-12

Materials for Each Student

• A copy of the narrative portion of this article

• Activities 1-5, including maps of Polish Partitions and Polish parishes in Chicago

• Bibliography for more specialized studies on the Poles and other groups in Chicago

Objectives for Each Student

• To explore the larger outlines of the Polish immigration

• To compare and contrast the Polish experience in Chicago with other major groups: Blacks, Hispanics, Jews, Irish, Germans, Italians, Bohemians, Scandinavians, and Asians

To weigh the historical consequences of multi-group cooperation and the search for common ground in the urban setting

To study the issues surrounding ethnocentrism and the efforts to retain group identity in a multicultural setting

SUGGESTIONS FOR

TEACHING THE LESSON

|

Opening the Lesson

It is expected that few students, unless they are of Polish descent, will have an adequate conceptual background of even the larger outlines of Polish and Polish-American history. Accordingly, it is suggested that students gain some familiarity with Polish history in the Partition period. This will entail some basic reading and research at local libraries and the use of inter-library loan.

In addition to suggestions in the bibliography that accompanies this article, students and teachers may wish to consult, for example, Norman Davies, Goaf's Playground: A History of Poland (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), or his abbreviated treatment, Heart of Europe: A Short History of Poland (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981). Each student might be assigned to give a brief report on a particular aspect of Polish history in the Partition period. Students might also prepare follow-up reports on particular aspects of the Polish contributions to Chicago and Illinois history — politics, religion, society, labor, culture, and education.

Developing the Lesson

Activity 1 has students comprehending geography's impact on the Partitions with a study of Poland's location vis-a-vis the partitioning powers. Students will quite naturally be drawn into a discussion of the implications and consequences of the Polish state's dismemberment and the subsequent impact on the rise of ultra-nationalism on the part of the Polish citizenry. Have the students discuss the fallout of the disappearance of any nation-state over a 150-year period in order to inaugurate the lesson. If they can become familiar with the concept of "arrested national development," they will begin to understand the origins of "ethnic cleansing" in Eastern Europe.

28

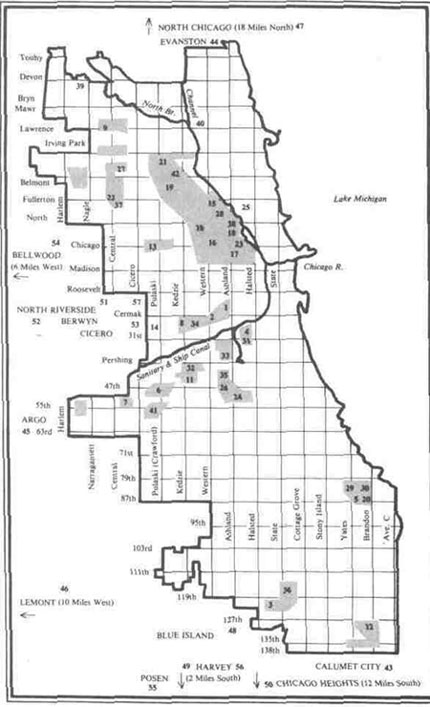

Activity 2 will enable the students to comprehend the spread of Polish settlements in Chicago. In the process, many of them will undoubtedly notice the proximity of Polish settlements to Black, Hispanic, and Jewish settlements in the city. They will also see the spread of many of the Polish national parishes in the historic process. Students of Jewish descent might make good use of Irving Cutler's The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb (Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 1996) or Allan H. Spear's Black Chicago: The Making of the Negro Ghetto 1890-1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967) to trace the development of Jewish synagogues and Black Protestant churches, which can then be compared to Polish Catholic church growth. Hispanic students might also do the same, as many Polish Catholic churches by the 1960s became major entrance points for the Hispanics into the wider Chicago community.

Activity 3 enables students to view the creation and development of an "ethnic ghetto." It allows students to view the actual names of people living in a particular census enumeration district. Students will notice that in certain instances the Polish group tended to occupy an entire neighborhood; at other times they will notice patterns of greater assimilation. In any event, once the students are trained to look for population succession patterns, they can adopt the techniques to study any group in the city.

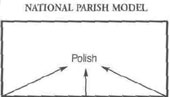

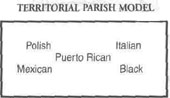

Activity 4 will emphasize the basic distinctions between national and territorial parishes and their overall impact on the development of ethnic settlements in Chicago. The activity will undoubtedly lead to heated debate, just as it did in 1920 Chicago Polonia!

Activity 5 might be used to gain some insights as to the current situation in Chicago. There are numerous Internet websites on Protestants, Catholics, and Jews in the city and suburbs, on different ethnic groups (Polish and others), and on Black and Hispanic groups.

Concluding the Lesson

It is essential for high school students in multicultural Chicago and other urban areas in the state of Illinois to reach out to various ethnic, religious, and racial groups. This article hopes to alert students to the complexities, historical and otherwise, of the multicultural process. This outline study of Polish Chicago can be used as a base for comparative studies of other major groups in Chicago and the state of Illinois.

Extending the Lesson

If at all possible, teachers and students should visit the Polish Museum of America at 984 N. Milwaukee Avenue in Chicago, phone: (773) 384-3352. The museum has a rich collection of source materials, exhibits, art collections, and historic documents that can enrich the ongoing activities of any multicultural classroom. Numerous other ethnic, religious, and racial groups in the city of Chicago and the state of Illinois maintain similar museum and archive facilities; and can be visited for comparative study. This will encourage students to appreciate the rich multicultural heritage that surrounds them.

Assessing the Lesson

Students may wish to actively debate the "Melting Pot" hypothesis, the arguments in favor of "cultural pluralism," the arguments for and against ethnic, religious, and racial isolation, as well as the search for "common ground" in the American form of democracy.

29

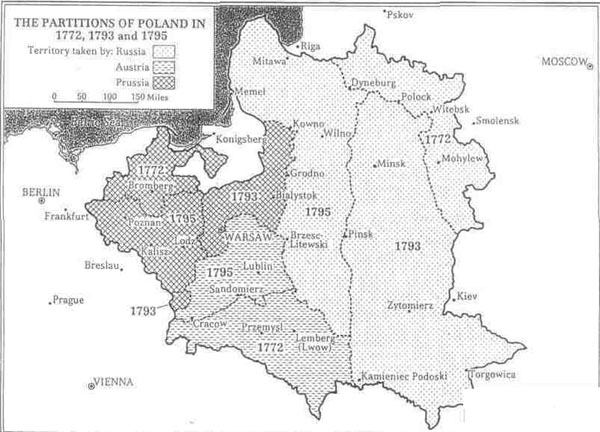

The maps clearly outline the demise of the Polish state during the period 1772-1795. Note the large territorial areas taken by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. In what ways did the Partitions spur the growth of Polish nationalism in the nineteenth century? When Poland was liberated after World War I, what did the new map of Poland look like in comparison to the pre-Partition map? Because the Polish people were without a state for nearly 150 years, why do you think that Polish leadership in Europe and America tended to distrust peoples of non-Polish descent? Finally, discuss the major distinctions between the terms "patriotism" and "nationalism."

Source: John Dayle Klier, Russia Gathers Her Jews: The Origins of the

"Jewish Question" in Russia, 1772-1825

(DeKalb; Northern Illinois University Press, 1986), p. 18.

Courtesy: Northern Illinois University Press

Map One: Partitioned Poland

Source: Joseph John Parot, Polish Catholics in

Chicago,1850-1920: A Religious History

(DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1981), p. 25

Courtesy: Northern Illinois University Press

30

The map of Chicago shows the locations of all Polish parishes in the city founded between 1867 and 1950. Although Polish immigrants settled in all parts of Chicago, note the large concentrations of Polish Catholic parishes in certain areas. Using some of the secondary sources outlining the histories of other groups in Chicago (for example, Jews, Blacks, and Hispanics), where did the Polish ethnic group come in close contact with other minority groups over the past century? Based on some of the secondary accounts listed in the bibliography what particular difficulties did Poles have when they encountered other minority groups? Historians of the process of cultural pluralism are fond of pointing to particular distinctions between minority groups. In what ways were the Poles markedly different from neighboring groups? On the other hand, some historians of assimilation point to areas of "common ground" on which differing groups come together. In comparing the history of the Polish in Chicago to other minority groups, can you detect any areas of agreement on vital urban issues — housing, education, health care, religious worship, social reform, jobs,and politics?

Map Four: Polish Parishes in Chicago, 1867-1950

Source: Joseph John Parot, Polish Catholics in Chicago, 1850-1920:

A Religious History(DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1981), p. 233

Courtesy: Northern Illinois University Press

31

|

Map No. and

Parish Address

|

Date

|

Administration

|

Teaching Order of Nuns |

|

1 St. Adalbert • 1650 W. 17th St. • Lower West Side |

1873 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

2 St. Ann • 1814 S. Leavitt • Lower West Side |

1903 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

3 Assumption B.V.M. • 544 W. 123rd St. • West Pullman |

1902 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

4 St. Barbara • 2859 S. Throop • Bridgeport |

1910 |

Diocesan |

St. Joseph (of the Third Order of St. Francis) |

|

5 St. Bronislaus • 8708 S. Colfax • South Chicago |

1920 |

Franciscan (O.F.M. Conv.) |

Felicians |

|

6 St. Bruno • 4749 S. Harding • Archer Heights |

1925 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

7 St. Camillus • 5430 S. Lockwood • Garfield Ridge |

1928 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

8 St. Casimir • 2226 S. Whipple • Lower West Side |

1890 |

Diocesan |

Resurrectionists |

|

9 St. Constance • 5843 Strong • Jefferson Park |

1916 |

Diocesan |

School Sisters of Notre Dame (S.S.N.D.) |

|

10 St. Fidelis • 1406N.Washtenaw • West Town |

1920 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

11 Five Holy Martyrs • 4327 S. Richmond • Brighton Park |

1908 |

Diocesan |

Franciscan Sisters of B.K. |

|

12 St. Florian • 13145 S. Houston • Hegewisch |

1906 |

Diocesan |

Franciscan Sisters of B.K. |

|

13 St. Francis of Assisi • 932 N. Kostner • Humboldt Park |

1909 |

Diocesan |

Franciscan Sisters of Our Lady of Perpetual Help |

|

14 Good Shepherd • 2719S.Kolin • South Lawndale |

1907 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

15 St. Hedwig • 2226 N. Hoyne • Logan Square |

1888 |

Congregation of the Resurrection (C.R.) |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

16 St. Helen • 2315 W. Augusta Blvd. • West Town |

1914 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

17 Holy Innocents • 743 Armour St. • West Town |

1905 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

18 Holy Trinity • 1118 Noble St. • West Town |

1872 |

Holy Cross Fathers (C.S.C.) |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

19 St. Hyacinth • 3636 W. Wolfram • Avondale |

1894 |

C.R. |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

20 Immaculate Conception • 2944 E. 88th • South Chicago |

1882 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

21 Immaculate Heart of Mary • 3834 N. Spaulding • Irving Park |

1912 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

22 St. James • 5730 W. Fullerton • Belmont-Cragin |

1914 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

23 St. John Cantius • 825 N. Carpenter • West Town |

1893 |

C.R. |

S.S.N.D. |

|

24 St. John of God • 1234 W. 52nd • Back of the Yards |

1906 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

25 St. Josaphat • 2311 Southport Ave. • Lincoln Park |

1884 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

26 St. Joseph • 4821 S. Hermitage • Back of the Yards |

1887 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

27 St. Ladislaus • 5345 W. Roscoe • living Park |

1914 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

28 St. Mary of the Angels • 1825 N. Wood • Logan Square |

1897 |

C.R. |

Resurrectionists |

|

29 St. Mary Magdalene • 8426 Marquette Ave. • South Chicago |

1910 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

30 St. Michael • 8237 South Shore Drive • South Chicago |

1892 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

31 Our Lady of Pepetual Help (St. Mary of Perpetual Help)1039 W. 32nd St. • Bridgeport |

1883 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

32 St. Pancratius • 4025 S. Sacramento • Brighton Park |

1924 |

Diocesan |

Franciscan Sisters of B.K. |

|

33 SS. Peter and Paul • 3745 S. Paulina • McKinley Park |

1895 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

34 St. Roman • 2311 S, Washtenaw • South Lawndale |

1928 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

35 Sacred Heart • 4600 S. Honore • Back of the Yards |

1910 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

36 St.Salomea • 11824 S. Indiana • Pullman |

1898 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

37 St. Stanislaus Bishop and Martyr • 5352 W. BeldenBelmont-Cragin |

1893 |

C.R. |

Franciscan Sisters of B.K. |

|

38 St. Stanislaus Kotska • 1351 W. Evergreen • West Town |

1867 |

C.R. |

S.S.N.D. |

|

39 St. Thecia • 6725 W.Devon • Norwood Park |

1928 |

Diocesan |

Resurrectionists |

|

40 Transfiguration • 2609 W. Carmen • Lincoln Square |

1911 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

41 St. Turibius • 5646 S. Karlov • West Elsdon |

1927 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

42 St. Wenceslaus • 3400 N. Monticello • Avondale |

1912 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

Suburban Polish Roman Catholic Parishes, 1883 -1950 |

|

43 St. Andrew the Apostle • Calumet City |

1891 |

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

44 Ascension • Evanston |

1912 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

45 St. Blaise • Argo |

|

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

46 SS. Cyril and Methodius • Lemont |

1883 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

47 Holy Rosary • North Chicago |

1904 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

48 St. Isidore • Blue Island |

1900 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

49 St. John the Baptist • Harvey |

|

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

50 St. Joseph • Chicago Heights |

|

Diocesan |

Franciscan Sisters of O.L.P.H. |

|

51 St. Mary of Celle • Berwyn |

1909 |

Benedictine (O.S.B.) |

Benedictine Sisters of Sacred Heart |

|

52 Mater Christi • North Riverside |

|

Diocesan |

Sisters of St. Francis of the Holy Family |

|

53 Our Lady (St. Mary) of Czestochowa • Cicero |

1895 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

54 St. Simeon • Bellwood |

|

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

55 St. Stanislaus • Bishop and Martyr |

1894 |

Diocesan |

Felicians |

|

56 St. Susanna • Harvey |

|

Diocesan |

Holy Family of Nazareth |

|

57 St. Valentine • Cicero |

1912 |

Diocesan |

St.Joseph |

|

Note: A Polish Roman Catholic parish is defined here as follows: 1) The parish was founded, organized, and administered on a predominantly Polish basis; 2) the parish was ministered to by Polish priests for the greater part of 1867-1950; 3) the parish school was administered by Polish orders of teaching nuns or Polish nuns belonging to other orders; 4) the parish population was predominantly Polish up to 1950 (i.e., the Poles were the largest nationality group belonging to the parish); 5) as late as 1950, the parish was ministered to by priests with Polish surnames and by Polish teaching nuns.A number of "Polish" parishes were omitted from the list; St. Boniface (1864) in West Town, and St. Wenceslaus (1863) on the near west side, because they were mixed nationality parishes; St. Mary of Mount Carmel (1892), a Resurrectionists parish, because it was largely Italian; All Saints, in West Town, because it belonged to the Polish National Catholic Church; St. Stephan on the Lower West Side, because it was heavily Bohemian (Czech); St. Szczepan, in West Town, because it was closed during the period; and Ascension, in Harvey, because it did not maintain its original Polish base. The scale has been distorted on the map so as to include all the suburban parishes. The distortion is minimal for those suburbs immediately surrounding Chicago and greater for suburbs on the far periphery of the city (e.g. Lemont). Where dates for suburban parishes were questionable they were omitted. Sources for the map: The New World, 26 November 1976, pp. 15-18; Swastek, "Contribution of the Poles"; Thompson, Diamond Jubilee; Iwicki Resurrectionist Studies; Local Community Factbooks; the Official Catholic Directory.

|

32

As a group activity, it is suggested that the class study the U.S. Census Bureau, Federal Population Census Manuscript Schedules in order to draw a social portrait of the Polish immigrant communities in Chicago. For instance, the Polish community in the "Polish Downtown" district in the 1900 census is located in microfilm roll number 267, enumeration districts 520, 526, 527, 528, 529, and 531. Most large public libraries have the microfilm editions of the census (as does the Illinois State Historical Library in Springfield, Illinois). Once you locate the census manuscript schedules, here is what you will find on the page:

28 columns of information on every individual recorded in the following order:

Address

Name

Relation (Father, Mother, Son, Daughter, relatives)

Race

Sex

Date of birth

Age

Marital status

Years married

Number of children ever born (of the mother)

Number of children still alive

Place of birth of person and their parents

Citizenship data

Occupation, trade, profession

Educational data

Literacy

Home ownership, rental, farm

Utilizing this census data for Polish (or other minority groups), one can arrive at fascinating social portraits of a given community or communities. Students might also use the census to compare ethnic groups. For the Italian community in 1900 in the Hull House area, see roll number 269, enumeration districts 599-600; for Jews on the Near West Side, see roll 269, ED 616; for Irish in Bridgeport, see roll 250, ED 157,158, 159; for Bohemians in the Pilsen area, see roll 254, ED 237; for Germans in Lakeview, see rolls, 276-277, ED 803 and 816.

33

In a classwide debate, discuss the positive and negative effects of national and territorial parishes. In all fairness, not all historians of ethnicity in Chicago agree with all positions taken in this article. Some scholars (see bibliography) have argued that the national parish gave a particular ethnic group a sense of social cohesiveness, a sense of ethnic pride, a common language form of religious and liturgical worship, and a spirit of community in an otherwise large impersonal urban environment. Critics of the national parish form of organization have argued that national parishes have tended to be overly suspicious of outside ethnic and minority groups and that national parishes have resisted the "melting pot" assimilation process. On the other hand, territorial parishes, which theoretically were supposed to include all groups within a given neighborhood, have often ended up doing just the opposite, especially when territories were drawn up to exclude minorities.

All Poles from any area of the city attend

a national Polish parish located outside

their neighborhood

|

All ethnic/minority groups

living within the territorial

boundaries attend the parish

|

34

Students may wish to access the following websites to gather more materials on topics related to this article:

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago: http//www.archdiocese-chgo.org/

Chicago Area Jewish Homepage: http://miso.wwa.com/

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP):

http://www.bun.com/assocorg/naacp/naacp.htm/

Churches of Illinois Online (Directory):

http://churches.net/churches/illinois.html

Immigration History Research Center (University of Minnesota):

http://www.umn.edu/ihrc/ihrcnews.htm

Note that these sites will also provide dozens of additional links.

Click Here to return to the Article

35

|