|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

David E. Cassens The industries of southwestern Illinois were magnets to numerous immigrants at the turn of the twentieth century. Located directly across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, the booming factories of the tri-city area of Granite City, Madison, and Venice attracted significant numbers of Bulgarian peasants and laborers. From 1900 to 1918 the tri-city area was know as the capital of Bulgarian immigration in North America. The history of Bulgaria and the Balkans is one of almost continuous war, revolution, and immigration. Originally from Asiatic stock, Bulgarians developed their nationalism and culture long before the fourth century A.D., when they moved westward. One group migrated deep into the Balkan Peninsula in 670 A.D., conquering the more numerous Slavic tribes in the region. Eventually the two cultures merged, and the Bulgarians became a Slavic-speaking people, linguistically related to the Czechs, Poles, Russians Serbs, Slovaks, and Slovenes. The Bulgarians were christianized in the beginning of the ninth century by disciples of Cyril and Methodious, the "Apostles of the Slavs," and they adopted the Cyrillic alphabet. The Ottoman Turkish Empire conquered Bulgaria in the fourteenth century, and thereafter the Christina population was subject to suspicion and persecution. After each war involving the Ottoman Empire, Bulgarians fled to safer territory.

Bulgarians were relative late comers among immigrants, but their arrival coincided with the early years of Granite City, which had been founded in the 1890s by two St. Louis brothers seeking a new location for their graniteware factory. The Niedringhouses' choice of Illinois for their new factories was based on several economic considerations. Industrial sites on the east side of the Mississippi cost half as much as those in St. Louis, and they were significantly more convenient than land west of the city. Moreover, Illinois sites were within twenty-five minutes of the St. Louis business district and could be reached by three bridges spanning the Mississippi. The Bulgarians who settled in the tri-city area were overwhelmingly male and had come predominately from the Bulgarian speaking parts of Macedonia. Among the eight thousand to ten thousand Bulgarians living in the tri-cities in 1905, only four family units were recorded. This important fact reflects the Bulgarian's assumptions about immigration. Initially, families did not immigrate. It was too expensive for most, and

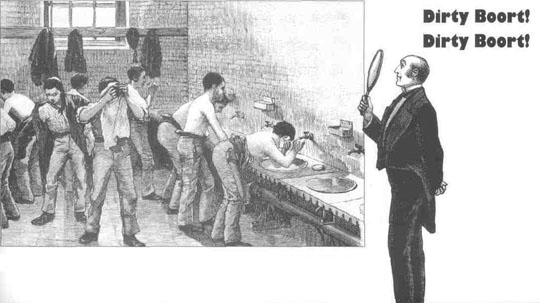

52 many family heads feared exposing their family to an alien culture such as America's. The sons of many immigrants remained behind on their Bulgarian farms, to which the family heads could return after earning money in America. The pattern of lone male immigrants prevailed through World War I. Living conditions in the bachelor boarding system, know as the boort, were depressing and unsanitary. Ten, fifteen, and twenty or more immigrant men lived in a single rented house or apartment. The boarders would sometime elect one among them to keep account, order provisions, collect rents, and pay bills. Some boorts hired a woman to cook or wash. The boarding houses were small, badly ventilated, and always overcrowded. Since many of the factories worked round the clock, men on different shifts might share a bed. Some rooming houses were operated by owners of saloon or grocery stores. With rents from $5 to $8 per person, an owner could collect $250 per month. In addition, tenants might be obligated to patronize the landlord's establishment or to rely on him as a banker. In such situations, landlords took the workers' pay on deposit but paid no interest, overcharged for groceries, and sometimes did not return the money. For the earliest waves of Bulgarian immigrants, there was no club room, no reading room, and no religious institutions for uplift. Social life centered around the coffeehouse and saloons. Bulgarians were outnumbered in the tri-city work force by Poles and Czechs, but were more numerous than Slovaks, Croats, Slovenes, Serbs, Ukrainians, and the three non-Slavic groups — Greeks, Hungarians, and Lithuanians. East Europeans concentrated along both sides of Madison Avenue, the boundary between Granite City and Madison. Bulgarians settled in West Granite, near the American Steel Foundries and the Commonwealth Steel Company, in a neighborhood know as Hungary Hollow. Prior to 1904 the majority of immigrants in the area of West Granite were Hungarian. After that date, however, they were supplanted by large numbers of Bulgarians. The newcomers had little industrial training and most arrived with little money. Many of those who did own land mortgaged it for passage to America. Most could not afford to have their family accompany them, or perhaps they feared failure in the New World. They came at the recommendation of friends and relatives, although a few responded to job announcements posted by steamship and railroad companies. They found an abundance of unskilled jobs, mainly in the steel mills, rail yards, lead works, meatpacking plants, or barrel works. The year 1907 was historic for the tri-city Bulgarian community because it saw the construction of a church, the founding of two newspapers, and the onset of a devastating depression. In the spring of 1907 the Eastern Orthodox Church board culminated a year-long fund drive throughout the tri-city area to build a Bulgarian Orthodox Church, which would be the first in the United States. Contributions had been collected

53

with surprising ease, and a one-hundred-foot lot on Madison Avenue between Thirteenth and Fourteenth streets in Granite City was purchased. Construction of a church proceeded rapidly. Meanwhile, Protestant efforts were also underway. Bulgaria had attracted American missionaries in the mid-nineteenth century, winning many converts from the Orthodox Church. Foremost among the missionaries had been Congregationalists, Presbyterian, and Methodists. In the tri-city area, the most influential minister among the Bulgarians was Tzvetko Bagranoff, a Presbyterian who had arrived in Madison in December of 1907. Bagranoff, a native Bulgarian, had responded to a call for an English-speaking Bulgarian minister by the Illinois Home Missionary Committee of the Presbyterian Church. The stock market crash of October 22,1907, accelerated the move to depression in the United States. Furnaces and foundries in Granite City and Madison shut down. Some Bulgarians who had achieved what they set out to do returned home. Most remained, and many lost money when the grocery or saloon in which they had deposited their savings went bankrupt. By the spring of 1908 all industrial activity ceased. Almost six thousand Bulgarians became idle in the tri-cities. "Hungary Hollow" was grimly renamed "Hungry Hollow." The roof of the Orthodox church was completed, but the congregation was unable to continue payments, and their total investment of $10,000 was lost. Despite that setback, the Holy Synod of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in Sofia sent priests to the tri-cities to help revitalize the faithful and to plan for a new church. A small church was finally built in 1909 and dedicated to Saints Cyril and Methodious. By 1910 recovery of the tri-city Bulgarian community was evident. Granite City boated a population of 9,903. Twelve factories employed 87,875 men and women. There were twelve churches and three banks. Madison, with a population of 5,046, had four factories that employed 3,450 men. Venice, too, saw its population grow dramatically. A third Bulgarian newspaper Rabotnicheska Proisveta (Worker's Enlightenment), was founded as a biweekly in 1910. Socialist in its politics, Rabotnicheska Proisveta was allowed to share the presses of the largest Bulgarian paper, Naroden glas (People's Voice). The two newspapers also cooperatively ran the best and largest Bulgarian bookstore in the United States. They maintained a thriving mail order business and published pamphlets on radical, political, and educational themes. A third Bulgarian newspaper founded in 1911 in Granite City, Makedonska glas (Macedonia Herald), sought to inspire Macedonian revolution and independence. The paper was unable to attract sufficient support and ceased publication after a few months. Another short-lived newspaper with a socialist slant was Narodna Prosveta (People's Enlightenment), which began in Madison but ceased publication after only a few issues. All of the Bulgarian institutions mobilized when the tri-cities reacted to events leading up to the First Balkan War in 1912. Between March and October of that year, the Balkan states of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro signed a series of defensive and offensive treaties intended to expel the Turks from Europe and unite fellow nationals. Before long, word reached Illinois that Bulgaria was preparing for war against the historic enemy. Many believed that the only way to help their homeland was to return and volunteer for military service. Colony leaders called a series of meetings to determine what measures should be taken. Communication was maintained with local Greeks, who also were trying to organize returnees to the Balkans. On Sunday afternoon, October 6, 1912, the first large-scale Bulgarian rally in Granite City drew more than six hundred Illinois Bulgarians. Several leaders, notably 54

Bagranoff, Chris Nedelkoff, and a man named Capidancheff, gave rousing speeches in defense of their homeland. Bagranoff estimated that there were as many as three thousand local Bulgarian, Serbs, and Greek who were willing to enlist. He also stated that several people had received warnings from relatives that if the Turks were victorious their land would be confiscated. Such news was particularly chilling to Bulgarian men who had left their families behind. By the end of October only a few men had returned to the Balkans. A committee of five collected $900 to defray expenses for the returning patriots, but that amount was not sufficient for the five hundred men willing to enlist. Since the Balkan governments offered no financial assistance to men willing to fight, only those who could afford their own passage could volunteer. Bagranoff guessed that the twenty or thirty Turks living in Granite City were simply too poor to return. The newspaper Naroden glas led much of the fund raising, and in all netted $20,000 for the Bulgarian Red Cross. One Granite City bank patronized by immigrants reported that more than $50,000 was withdrawn just before and after the outbreak of the war. Early on the morning of October 30, the first group of five hundred Greeks and Bulgarians prepared to leave for New York. The community had arranged a day-long celebration. First, the men gathered in formation and marched through Hungry Hollow. Led by the Granite City Marching Band, they carried the American flag and those of the Balkan nations. Many wore the uniform of their native lands, and some carried weapons. For twelve hours along the line of march around the railroad depot there were band concerts, drills, and impassioned renditions of patriotic songs. The first group of 150 left in the morning, the second in the afternoon, and the last group of two hundred departed in the evening. Bulgarian and Greek songs were sung between choruses of "America" and "Rally Round the Flag" as each contingent left. Five hundred more Bulgarians were expected to leave within the week. Bulgarians who were unable or too fearful to return to the Balkans were preoccupied with the news of the war and the safety of their families. They sent a steady flow of money and clothing to their native country, and they apparently seldom questioned the aggressive action taken by the Bulgarian government and its allies in 1912. At the outbreak of the Second Balkan War on June 30,1913, four Bulgarians beat and stabbed Tony Zuralli, who had questioned the bravery of the Bulgarian army. The attack took place outside the Little Six Bar in West Granite. Zuralli survived, and his attackers were jailed. Such incidents, although rare, reflected the passionate feeling of the Bulgarians. European unrest leading to World War I also aroused Bulgarian nationalism. When their native country joined the Central Powers in 1915, some Illinois Bulgarians, like many German Americans, were regarded as possible enemy agents. Naroden glas urged American neutrality, collected donations for the Bulgarian Red Cross, and sent money to Bulgarian prisoners in France. With America's entrance into the war on the side of Britain and France, there were new difficulties in the Bulgarian colony as some men returned to to fight. Two local,

55

Presbyterian ministers protested to the Illinois Synod that Rev. Bagranoff's Bulgarian Mission in Madison had become seditious. The synod withdrew its support, and Bagranoff was forced to move his mission across the river to St. Louis. The defeat of Bulgaria as an ally of the Central Powers and the transfer of Macedonia to the new Yugoslav state created many bitter feeling among the Illinois Bulgarians. Naroden glas protested against the harsh Treaty of Neuilly, which Bulgaria was forced to sign. Some men who had enlisted in the Bulgarian army returned to the tri-cities, many with families. By 1919 there were as many women and children as men in the colony.

Life was changing in the many ways for the Bulgarians. The Bulgarian bookstores now issued publications on business, politics in the United States, citizenship information, English language instructions, and annual almanacs. Interestingly, before 1919, more Bulgarian socialist, communist, and revolutionary titles were printed in the United States than in Bulgaria, much of it coming from Granite City. Overall, however, the bookstores selling Bulgarian-language newspapers experience a slow but steady decline in the postwar period, a result of both the decline in immigration from the Balkans and a wider dispersal of Bulgarians throughout the Untied States. Also, as Bulgarian men and women chose American spouses, the ethnic identity of families weakened. Many Bulgarian parents did not pass on the language to their children. Although no Bulgarian-language newspaper survives in the tri-cities today, ethnic names are very common — Popov, Tsigalerov, and Tarpoff, for example — and those families can recollect their heritage. They represent the unique area north of East St. Louis that from 1900 to 1918 was the largest center of Bulgarian ethnicity in North America. Click Here for Curriculum Materials 56 |

|

|