In the 1830s land speculators hoped that the area around the mouth of the Calumet River would connect shipping routes on the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes. The Indians were moved to reservations in 1835 and Irish immigrants settled in the area. In the 1840s and 1850s, small industries located near the river and railroads laid tracks between Chicago and Calumet. After 1869, when the canal and harbor were improved by private enterprise and the federal government, the area grew rapidly. Steel mills soon dominated the area, although grain elevators, railroad shops, and lumber yards were also important. Immigrant workers who were attracted by thriving industries streamed into new housing subdivisions. In 1889, when Calumet was annexed to Chicago, half of its 26,500 residents were foreign-born. Poles were the largest group.

Between 1890 and 1930 the community, now known as South Chicago, continued to expand. As more mills were constructed, the population increased to more than 56,600, including significant Mexican and black populations. South Chicago reached maturity between 1930 and 1960. The area had an established commercial strip, many

community institutions, and an industrial base. The majority of all housing units were single-family dwellings. Although there was still much vacant land for development in South Chicago, the area's overall population began to decline. Nevertheless, in the 1970s, the Mexican-American and black populations continued to increase. The closing of the area's many steel mills in the 1980s caused bitterness among workers and economic hardship. Today the community faces questions about how to use its remaining wetlands near the lake and how to reuse the obsolete industrial facilities.

3. Analyze primary source documents.

16.A. Apply the skills of historical analysis and interpretation.

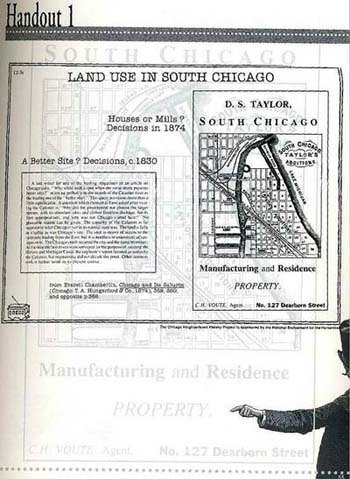

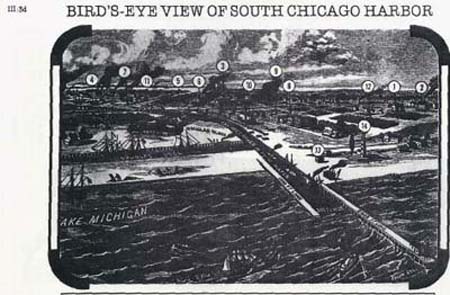

A. Compare the map of Taylor's additions to the "Bird's-Eye View of South Chicago." (Handout 1)

1. Note the entrance to the river. These improvements were made between 1870 and 1873, creating a safe harbor for commercial ships.

2. Locate the Douglas Slip, the Douglas Dock, and the Douglas Block on each document.

a. Note the old farm buildings

in the Bird's-Eye View.

b. Note the workers improving

the dock.

c. The hotel on the map housed workers building the new Silicon Steel Mill.

B. How should the land be used in Taylor's additions?

1. The advertisement indicates that the land can be used for manufacturing or residences. This was before zoning laws governed the use of the land.

2. Everett Chamberlain pointed out that the "natural attractions of the lake shore" would make "for excellent residence sites."

3. How do you think the area around the old farm house should be developed? How should Taylor's land be used?

V. Past and Present: United States Steel—South Works

A. Handout: "The Iceman Remembers", "South Works:

Death Watch at a Steel Mill," Chicago Sun-Times, October 30, 1983(Handout 2).

1. Past glories

a. Growth

b. Work force

c. Contribution to the city and the nation

2. Decline

a. Shutdowns in other cities

b. Isolated operations at South Works are shut down

c. South Works called "marginal" by the U.S. Steel Company

d. Foreign Competition

e. Massive layoffs

f. The Iceman's changing role

3. Questions

a. What mood does the term "Iceman" convey in this article?

b. How would you divide the history of South Works into periods?

c. What were the high and low points in the history of South Works?

VI. Workers' Perspective on the Decline of South Works and South Chicago

A. The Call for a New Technological Base:

1. Status of the mill

2. Status of the national infrastructure

3. The union's proposal

VII. Land-Use Decisions Continue in the Calumet River Basin

A. Filling in the wetlands today

1. Waste disposal: landfill operations

2. Created land for harbor facilities and industries

3. But, shouldn't some natural areas be preserved?

4. And, shouldn't some wetlands

be used for recreation?

B. Obsolete factories and mills: What should we do with them?

1. A landscape of neglect

2. The need for jobs

54

55

1. South Chicago Hotel

2. Site Sinclair's Woolen Mills, and Kent, Baldwin & Co.'s Machinery Manufactory

3. Railroad Station Buildings of Pittsburgh & Fort Wayns and Michigan Southern railroads

4. Location of Docks, Rolling Mills, BlastFurnaces, Elevators. Saw Mills, Etc.

5. Location of Ship Yard Dock

6. Location of Cotton Mills

7. Location of proposed Ship Canal to Lake Calumet

8. Casgrain House

9. Office of Calumst and Chicago Canal and Dock Co.

10. South Chicago Planing Mill and Lumbar Yard

11. Lake Calumet—three miles long and navigable for vessels

12. Logan Park

13. United States Government Engineer's Office

14. United States Lighthouse

from Everett Chamberlin, Chicago and Its Suburbs (Chicago: T.A Hungerford & Co., 1874 ), 369. 36C. and opposite p.368

The Chicago Neighborhood History Project is sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities

56

Handout 2

THE ICEMAN REMEMBERS

It was the 1960s and the Iceman was an on-the-rise supervisor at U.S. Steel Corp's South Works, a symbol of Midwest industrial might and heart of South Chicago. His name was John Freese, but "Iceman" was coined by those sensing a cold ambition underlying impromptu 4 a.m. patrols.

Freese, now the boss of South Works, still makes pre-dawn rounds about a 547-acre domain. But there's a muted sadness in his step and gaunt demeanor because so much around him in hushed—like a gargantuan, iron and brick cathedral where worshipping long ago ceased.

Any day, the

company is expected to announce a decision on whether to build a rail mill, proposed and heralded only two years ago as a commitment to the future—and stalled ever since. Regardless of the decision, South Works will never return to its former glory. Indeed, the company may decide to close it.

Freese, who began at the bottom in 1947 at 56 cents an hour, is a proud general whose army has been decimated by forces beyond its control. It has dwindled to 1,000 from a 1944 high of 18,000 and a post-war high of 15,000.

Only a feeble pulse beats where 10-story cranes and massive engines once hammered out a muscular beat, sending 26-ton ingots, aglow at 2,450 degrees, whipping along production lines end plumes of white smoke into the sky.

In those days, South Works set the rhythm for a seminal Chicago community. Waves of Irish, Swedes and Germans came first and in a non-union age, worked 12-hour days with a day off every two weeks.

With expansion came English, Scots, French Canadians, Poles, Slavs and, later, Mexicans and blacks, finding a new world on the grounds of a onetime Indian compound and fishing village.

In towering fashion, the City of Broad Shoulders is built upon the sweat of those customers and—given a legacy of fatalities and union battles their blood.

Nearly all Chicago's grand skyscrapers— the Sears Tower, John Hancock Center, Standard Oil Building. First National Bank—are framed in South Works steel. So are dams across the Mississippi River, ploughs in the Iowa farm soil, the nation's longest suspension bridge over the Mackinac Straits of Michigan and rocket assembly buildings at Cape Canaveral. Fla.

" It was the heart and soul of the neighborhood

and put bread and butter on people's tables."

—Ald. Edward R. Vrdolyak

That's why, especially in the boom years that followed World War II and extended

through the 1960s, Freese's ambition appeared anchored in a nation's seemingly insatiable appetite for steel and South Chicago's pride in making it.

This was a city within a city. It had its own police force, fire department, hospital, restaurants, power planet, telephone, portal and even school systems. It had its own racial and ethnic segregation.

A railroad ran on 135 miles of track, the distance between Chicago and Dubuque, Iowa. without leaving the mill. Being general superintendent was like being a mayor.

Bordered by Lake Michigan and the Calumet River, South Works was positioned perfectly near rails and water. Tagged "the pioneer steel plant of the West," it could produce and ship 5.5 million tons a year. It was the third largest in the world—pouring a steady stream of blooms and billets, beams and bars, channels, angles, rods and plate into an apparently unending market.

"Back in the '50s, we used to wonder where they were going with so much steel," said Ed Hojnacki, a 40-year mill veteran in the machine shop. "We worked nights, we worked weekends, and we couldn't seem to make enough."

Then in the late 1970s, the picture began to change. Throughout the nation, the industry began shutting down—in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York

and even the South Side, where Wisconsin Steel padlocked its gates.

At South Works, the shutdown of individual, isolated operations been to accelerate. First, the alloy bar mill in l975, then a foundry in 1978.

In 1977, in on interview with the Sun-Times, U.S. Steel Vice President Edward Smith shocked the city by calling South Works a "marginal facility" that was losing money. He gave the mill only a 50-50 chance of surviving.

The great mill he dearly loves may be dying.

In early 1982, U.S. Steel laid off nearly two third's of its remaining work force. The rail mill the company once said would create at least 1,000 new jobs was put on hold.

James Warren and Daniel Rosenheim, "South Works: Death Watch at a Steel Mill," Chicago Sunday Sun-Times (October 50, 1983).

The Chicago Neighborhood History Project

57

VII:4a

THE ICEMAN REMEMBERS (continued)

Draped in a thin layer of silicate, the modern basic oxygen furnace has been immobile since 1980. The emptiness is daunting.

Weeds and an eerie silence

Outside the mill, weeds sprout through the concrete in empty parking lots, and quiet reigns where the clanging streetcars once plied the mill-gates along avenues named Brandon, Green Bay, Mackinaw, and O.

Over there, says Freese, is where the open hearths used to stand. There was a blast furnace on that piece of ground, a rolling mill in that shed. It it like listening to an archeologist groping to reconstruct the past.

"Whadda'ya say, Harry" is Freese's occasional greeting to another old-timer. In a system ruled by seniority, only the senior remain. And then they leave, Freese, 56, retires Monday and will be replaced by a downgraded "plant manager" reporting to officials in Gary.

It's hard to realise that this place once boasted a softball league with 63 teams, a bowling league with 90 teams, a golf league with 54 teams, archery, swimming and tennis teams, a glee club, a 50 piece band and more.

It used to run three shifts, seven days a week. Now on some weekends, there are only six people in the mill—a couple of guards, a power station operator and a mechanic or two.

Walk, watch and listen. There are violets in the window boxes outside the electric furnace, l dab of color and life and the drabness of dust and decay. Still, the Iceman will mill just one more day. A final winter may be at hand.

"weeds sprout through the concrete in empty parking lots . . "

58