The four Freshmen

When the newest members of Illinois' congressional delegation arrived in the nation's capital, senior members welcomed them with parties. Reporters clamored for interviews. It was a brief moment in the spotlight before the back bench

by Toby Eckert and Dori Meinert

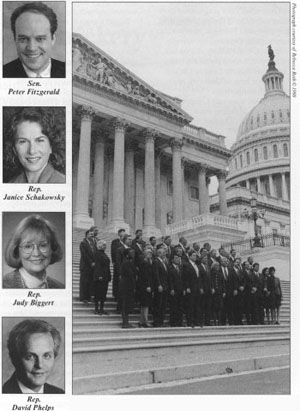

When Judy Biggert and Janice Schakowsky joined the other newly elected House members on the steps of the U.S. Capitol for the traditional freshman class portrait, they wore red to stand out. In the row behind them, rounding out the trio of newcomers from Illinois, David Phelps had a prominent position near the center of the crowd, albeit in a more conservative suit and tie.

It was orientation week and the world, or at least the nation's capital, seemed to revolve around them and the 37 other new representatives. Their views were sought on the Republican leadership shakeup and the presidential impeachment drama. Senior members welcomed them with dinners and cocktail parties. Reporters clamored for interviews.

It was a brief moment in the spotlight before the inevitable return to the relative anonymity of the back bench, where freshmen are more often seen than heard. A week later, the ritual was repeated for newly minted senators, including Illinois' Peter Fitzgerald.

The state's 22-member congressional delegation starts the 106th Congress with a lot less collective seniority than it had during last year's session. Biggert, a Hinsdale Republican, Phelps, a Democrat from Eldorado, and Schakowsky, a Democrat from Evanston, respectively, replaced veteran Reps. Harris Fawell, a Naperville Republican, Glenn Poshard, a Marion Democrat, and Sidney Yates, a Chicago Democrat, all of whom

retired, Poshard after an unsuccessful run for governor. Fitzgerald, a Republican from Inverness, ousted one-term incumbent Chicago Democratic Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun in the November election.

Still, despite the large number of new faces, little is different for the delegation. Biggert, Phelps and Schakowsky who served together in the Illinois House are taking the place of mentors and ideological soulmates, promising little deviation in voting records.

The biggest change in the delegation will be Fitzgerald, a 38-year-old former state senator and heir to a banking fortune. In sending him to Capitol Hill, Illinois voters exchanged a dependable liberal for a staunch conservative. Moreover, Fitzgerald and the state's senior senator, Democrat Richard Durbin, are political polar opposites in jobs that require a high degree of comity and cooperation, at least when the state's policy interests are at stake. While both have expressed a willingness to make common cause, their professional relationship is still a work in progress.

"I look forward to working with Senator Durbin," Fitzgerald says. "I have great respect for him, though I do think that he maybe is a little on the high-tax, big-government side than I would be. But I think that on areas where we would agree for example, transportation funding or helping with the agriculture community or the [financial] exchanges in Illinois there are going

to be a lot of areas where we will see eye to eye and our interests would certainly be aligned."

Says Durbin: "I've worked closely with Republican governors, as well as Republican members of the Illinois delegation. I think we do put partisanship aside when it comes to our state, and I plan on doing that with Peter Fitzgerald. You are a team [representing a statewide constituency]. It's a lot different from the House, where you're a free agent."

Although Illinois hasn't had senators from different parties since 1984, when Democrats clamped a 14-year lock on both seats, it is far from a unique situation. For most of his 18 years in office, the state's last Republican senator, Charles Percy, served alongside a Democrat, first Adlai Stevenson III and then Alan Dixon. But the ideological gulf is wider between Durbin and Fitzgerald than it was between the moderate Percy and his Democratic colleagues.

On national policy, Fitzgerald is likely to cancel Durbin's votes on issues ranging from taxes to abortion to flag burning. On a more parochial level, the two may clash on nominations for federal judge in Illinois. With a Democrat in the White House, tradition dictates that Durbin forward the names of potential jurists to the president, who places the nominations before the Senate.

Durbin is not likely to continue the joint selection process he and Moseley

18 / January 1999 Illinois Issues

Braun followed, though he indicated he may informally consult Fitzgerald. As a member of the majority party and the bearer of a powerful senatorial prerogative the ability to stall, indefinitely, votes on nominations Fitzgerald is not without leverage. Indeed, in recent years, Durbin and other Democrats have accused Senate Republicans of deliberately slowing scores of judicial confirmations for ideological reasons.

"It will be interesting," Fitzgerald coyly suggested.

During the fall campaign, Fitzgerald generally avoided discussion of policy and often kept reporters at arms' length. The scandals swirling around Moseley-Braun provided him with ample fodder for the stump and the air-waves. But that left him something of a cipher in the minds of many voters. Even fellow Republicans weren't sure what to expect from the wealthy banking heir.

As a state senator, Fitzgerald earned a reputation as a rather doctrinaire conservative, though he also had a habit of bucking Springfield powerbrokers on such issues as riverboat gambling and patronage. Asked before the election how he thought Fitzgerald would fit in with the rest of the generally moderate Illinois delegation, Peoria Republican Rep. Ray LaHood confessed: "I really don't know. You can have ideological points of view, but at some point you have to be willing to look at some of these things that are important to the state."

Fitzgerald insists he can do that, shrugging off Moseley-Braun's warning that he is radical and inflexible. Though he says he won't bend on core issues like opposition to abortion and taxes, during the campaign he sounded moderate notes on gun control, organized labor and education. Despite being a fiscal conservative, Fitzgerald indicated he would be comfortable in the role that Illinoisans often expect their Congress members to fill: federal breadwinner. He said he was eager to bring home more federal dollars for transportation and to protect tax breaks for the state's ethanol industry. He was appointed to two committees important to Illinois:

|

Agriculture and Energy. (However, Sen. Durbin's appointment to Appropriations the committee that controls the federal purse strings could have a bigger impact on the state.)

"Certainly, I think it's an obligation of our congressional delegation and our U.S. senators to make sure Illinois does not get short-changed, whether it's the funding formula for transportation dollars or for other discretionary spending," Fitzgerald says. "It's my obligation to make the case for the projects in Illinois that make the most sense."

Things are a little more predictable on the House side of Capitol Hill, at least as far as Illinois is concerned. The most noticeable change is the gender of two of the three newcomers. Judy Biggert and Janice Schakowsky joined a House delegation that has been all male since Chicago Democratic Rep. Cardiss Collins retired in 1996.

Ideologically, the three are in step with their predecessors. Like Harris Fawell, Biggert is rather conservative fiscally but liberal on social issues,

|

For the record: The House of Representatives freshman class poses for the traditional photograph in front of the U.S. Capitol. Janice Schakowsky is in the front row, second from the right. Judy Biggert is in the front row, seventh from the right. David Phelps is in the second row, fifth from the left. (Peter Fitzgerald is not in the shot)

|

Illinois Issues January 1999 / 19

Judy Biggert and Janice Schakowsky joined a House delegation that has been all male since Chicago Democratic Rep. Cardiss Collins retired in 1996.

reflecting a moderate, suburban outlook. Schakowsky comes from the liberal wing of the Democratic Party and shares Sid Yates' progressive North Shore views. David Phelps, hailing from deep downstate Eldorado, espouses the same populist Democratic conservatism as Glenn Poshard, playing to a district that, in some places, resembles Dixie more than the Land of Lincoln.

Certainly, none of them runs away from such comparisons.

"On policy questions, Congressman Yates and I will be very much the same, and I think that will please my constituents" in the 9th District, says the 54-year-old Schakowsky. "If people want to call that liberal, it's OK with me."

Indeed, the district is one of the most liberal in the state. It includes Chicago's affluent North Shore and neighborhoods with large immigrant populations, such as Uptown and Rogers Park, and close-in suburbs such as Evanston and Skokie.

Reflecting her background as a consumer activist, Schakowsky says her priorities are health care, consumer protections and the environment. She supports expanding Medicare to cover all Americans, not just seniors and the disabled, and backs the Democrats' health care reform plan, which would allow patients and their families to sue health maintenance organizations for improper care that results in injury or death.

The largest number of constituent cases in Yates' office involved immigration problems. "I have promised my constituents that one of the first things that I will do is to take on the [Immigration and Naturalization Service]," Schakowsky says. "There definitely is not a customer service attitude at the

INS."

She also pledges to carry on Yates' legacy as a national champion of the arts.

As much as Schakowsky represents the historic urban Democratic power base in Illinois, Biggert, 61, is an apostle of the suburban Republicanism that increasingly defines the state's politics. Her 13th District, which includes southern DuPage County and parts of Will and Cook counties, contains some of Chicago's fastest growing suburbs. It's home to numerous corporate headquarters, high-tech companies and scientific research organizations.

Biggert is eager to make a splash in Washington, D.C. Comparing herself to the unassuming Fawell, she says: "I'd like to be a little more out-front, more visible. When you have 435 members compared to 118 in the Illinois House, just to have people aware that you're there makes a difference."

She's wasted no time trying to make them aware. The minute her plane landed in Washington for freshman orientation week in November, Biggert rushed to a live CNN interview. She also made several appearances on C-SPAN. Those efforts were followed by an unsuccessful bid for freshman class president. Defying the conventional wisdom that first-termers should steer clear of turf battles among more powerful, senior colleagues, she plunged into the House Republican leadership dustup, lobbying for Rep. Jennifer Dunn, a Washington state Republican, as majority leader, another lost cause.

Seeing the Republican losses in the November election as voters' call for an end to partisan gridlock and for increased cooperation between political parties, Biggert says her main goal is "to restore faith in government." She says she also wants to push for improvements in education, restraints on government spending, reduction of the national debt, cuts in the capital gains tax, preservation of Social Security and Medicare and increased attention to women's health issues.

Far from Chicagoland is Phelps' 19th District, a sprawling region of southeastern Illinois anchored by Decatur on the north and the banks of the Ohio River on the south. A gospel-singing

Baptist, Phelps and his politics anti-abortion, anti-gun control, pro-union, pro-public works -- are as traditional in much of his district as the grits that go with breakfast. But in Washington, he's considered a "New Democrat," or at least a "Blue Dog."

The group of conservative Democrats who claim that name, to distinguish themselves from the knee-jerk "Yellow Dog" southern Democrats of the past, eagerly embraced the 51-year-old Phelps. The feeling is mutual. "I think they are an organization that will be more of an influence in the next few years," says Phelps. Indeed, with Republicans having only a 12-seat majority in the House, caucuses like the 29 Blue Dogs could make or break some of the GOP's agenda.

Like Poshard, Phelps wants to focus on the district's economy, rural health care and education. Portions of the district are making a sometimes painful transition from an economy based on the mining of high-sulfur coal. Phelps sees one of his roles as winning federal support to ease that transition by developing the tourist economy and a transportation infrastructure to attract other employers.

Agriculture is the lifeblood of the district, from the corn that is reaped in Massac County farm fields to the factories in Decatur where it is processed into ethanol and other products. So farm policy will be another priority for Phelps. "The issues I want to focus on are pretty much a continuation of what Glenn focused on and what I worked on in the legislature," he says.

However, Phelps won't be an exact replica of Poshard. He has already parted ways with his predecessor by accepting campaign money from political action committees and refusing to self-limit the number of terms he will serve. Nor will Phelps be inheriting a key piece of furniture from Poshard;

the air mattress the frugal congressman slept on in his office whenever he was in Washington.

"I'll have a place to stay here," Phelps says.

Toby Eckert and Dori Meinert are Washington correspondents for Copley News Service. They write for eight Copley-owned daily newspapers in Illinois.

20 January 1999 Illinois Issues