HIGH STAKES

Conflicting agendas put airport development in a holding pattern. But recent events could help put the subject back on the radar screen

Analysis by Burney Simpson

Location, location, location. That old real estate mantra sums up why Chicago became, and is today, one of the most important American cities. A central location always lent itself to the commerce of the day, whether goods were moved by foot, water, road, rail or air.

But the formula for success has changed. Commerce is now international, and being at the center of the country isn't necessarily a bonus. The hypothetical German banker or Brazilian tourist could just as easily fly straight to New York, or through Denver, as stop off at Chicago's O'Hare International Airport. The challenge today is to snare those travelers, while retaining the domestic business that makes Chicago the top city for flying.

Indeed, the state's position in the so-called global economy could well depend on how, even whether, Illinois officials meet that challenge. Certainly, they've begun deliberations on the best way to go about it — expand O'Hare and its sister Midway Airport, or build a new airport for the metropolitan area — though conflicting agendas have put the issue in a holding pattern for more than a decade.

But recent events may help to put the subject back on the radar screen, and could serve to refocus the discussion. Significantly, George Ryan was elected governor last November with a $20 million pledge to begin buying land for an airport near far-south suburban Peotone, a tangible step that other Republican leaders have not taken.

And late last year, a new study on the metropolitan region's airport capacity projected a jump in the number of air travelers to Chicago in the next 15 years, a finding by a pro-O'Hare group that managed to elicit cheers from all sides, also a first. The forces that want to expand O'Hare say, great, we'll accommodate growth with technology and bigger planes. Those who want to build a third Chicago-area airport say, terrific, let's break ground and prepare to accommodate those extra travelers.

If that kind of movement seems minor, it might be well to review the stakes, which are not.

First, a look at the numbers.

Consultant Booz, Allen & Hamilton, which conducted the new study, figures Chicago's airports, including tiny Meigs, are the largest economic stimulant in the region, contributing $35 billion annually and generating almost 500,000 jobs. And, they argue, capturing the future international travelers could generate another $26 billion.

Now for the politics. Better put up the tray tables; it's been turbulent and could be again.

Among the major players are the airlines, and the state and federal agencies that regulate air travel. There are officials who represent the communities around O'Hare and Peotone, including Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley, Republican U.S. Rep. Henry Hyde of Bensenville, and Democratic U.S. Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. from Chicago's South Side. And there's a squadron of northwest and south suburban mayors and state legislators.

Every position is grounded in selfinterest.

Here's a quick rundown. Chicago owns O'Hare and Midway, and Daley doesn't want to lose a single passenger or patronage opportunity; the airlines have invested heavily in making O'Hare a national hub and don't want to dole out more bucks for a new airport; Rep. Jackson believes a new airport in Peotone will generate jobs and business for his South Side working class district; Rep. Hyde and his affluent constituents in the northwest suburbs are sick of the noise and congestion associated with O'Hare; and the state supports the move for a third airport because the project could spread jobs and money.

And every interest can point to expert analysis for support.

In fact, the latest study is one of many done over the years. It was commissioned by the Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce, a business organization with 2,500 member firms that employ 1 million workers. The chamber also announced formation of the Midwest Aviation Coalition, headed by Ronald J. Gidwitz, chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Chicago City Colleges, and a friend of Daley's. The coalition says it will promote airport growth — and international travel — as a way to build the area's economy. But the group's focus is O'Hare, Midway and Wisconsin's General Mitchell Field, not Peotone.

Booz, Alien & Hamilton found that Chicago can remain the world's largest

24 / January 1999 Illinois Issues

|

air hub — and grab market share from other American airports — if it upgrades O'Hare and Midway, builds more capacity and targets the international traveler with more nonstop flights. Advanced landing technology and bigger planes, the argument goes, will allow the two airports to serve more travelers with little additional noise and pollution.

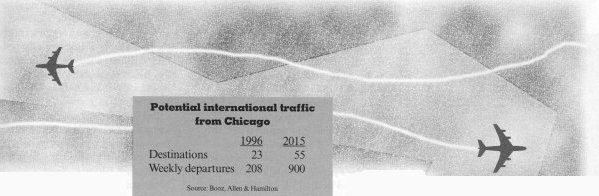

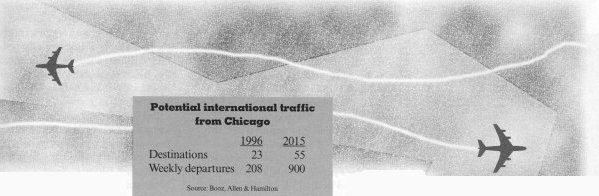

In fact, the study pushes hard for expanding O'Hare, arguing that a single airport is necessary to create a nonstop connecting point for domestic and international travelers. As the No. 1 domestic airport for connections, O'Hare has a leg up on that portion of the business. But Chicago lags in attracting international travelers, ranking a distant fourth behind New York, Miami and Los Angeles.

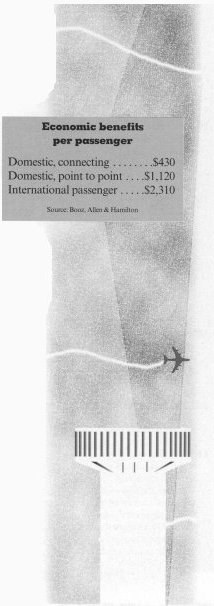

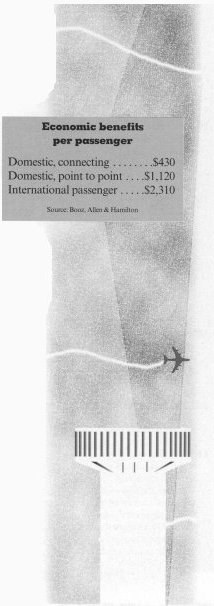

And international passengers are especially attractive because they can generate as much as $2,310 for the local economy for each passenger, compared to $430 for each traveler who takes a domestic flight and connects through O'Hare, according to the report.

Booz, Alien & Hamilton projects that the number of so-called "second tier" international cities offering nonstop service to America will double in the next 15 to 20 years, causing a fivefold increase in overseas travelers by 2020. To earn the potential $26 billion predicted by these consultants, O'Hare would have to serve 60 percent more travelers in the next 15 years, and twice as many passengers would have to use Midway

The study estimates that Chicago could garner 9 percent more internation-

al business from its three leading competitor cities. But, it also argues that if a third airport is built and O'Hare's role as a hub is diminished, the region could see a loss of $10 billion annually.

And there is an airport business logic to that argument, though it may seem odd that building a new airport for more flights would generate less money The calculation ¦ comes down to something called "perimeter rules," which may be imposed when a second airport is opened in a metropolitan area. These rules draw a figurative circle around the area to divvy up the business between the new and old airports. All traffic coming from or going to a destination outside the ring goes to the new airport; the old airport gets the closer flights. This is intended to give the new airport some flights, which should attract other airlines to set up shop there, too.

But, Booz, Alien & Hamilton argue the rules don't work.

For example, in the Washington, DC., metropolitan area, Dulles International Airport was built in suburban Virginia and a 650-mile perimeter rule gave it most of the international flights. Congested National Airport kept the domestic traffic. But these airports are about 30 miles apart, making the connection between the two inconvenient. As a result, the consultant report argues, Washington has never become a center for air travel like Chicago, though it is a natural for international travelers.

"Perimeter rules would be devast-

|

|

Illinois Issues January 1999 / 25

ating to O'Hare as an international hub." says J. Roper, president of the Chamber of Commerce. "If O'Hare is constrained, you choke it off. The local economy would be hurt, and the airlines would just fly over Chicago."

Those arguments mean the Booz, Allen & Hamilton study is a real feather for O'Hare backers, right?

Not entirely. The consultant also found that if a third airport is not built, the number of passengers moving through Chicago will grow anyway at a healthy 3 percent annual rate through 2015, and by that year O'Hare and Midway would be at maximum capacity. By then, the airports could be serving more than 63 million passengers.

That calculation bolsters third airport proponents because they have long argued that growth will exceed what O'Hare and Midway can supply. What the region should do now is open a smaller airport that can soak up some of the excess flights and grow over time, says Christine Cochrane, manager of the Third Airport Project at the Illinois Department of Transportation.

"They want to cram more into O'Hare," says Cochrane. "That might meet the area's need for the next 10 years, but they will soon have a full airport again. We want to build a new airport that will meet the area's needs 20 and 30 years from now."

Chicago has been reluctant to admit that travel in and out of its airports will grow at the 3 percent rate. Just last June, the city's Aviation Department issued its own study that projected an increase in air travel of 1.7 percent between 1997 and 2012, including domestic and international passengers.

Whatever the growth, the state argues that a third airport will relieve congestion and provide an economic payoff.

The transportation department has pegged the tab for a third airport at between $288 million for a facility with two runways and five terminals to $1.6 billion for three runways and 37 gates. But, according to the department, by 2020 a Peotone airport serving 31 million passengers would generate 236,000 permanent jobs and pump $16.7 billion

into the local economy.

Another issue for the state is that smaller Illinois cities are getting shut out of O'Hare, primarily because it costs so much to use a landing or take-off slot. The department estimates that each slot costs about $4 million, which forces carriers to give priority to the more lucrative international or long-haul flights.

But if the latest study fuels the argument for another Chicago metropolitan-area airport, so do two other developments. Last fall, the Commercial Club of Chicago issued "Chicago Metropolis 2020," a strategic guide for the future of the urban area. The report punted on the airport controversy, calling for both O'Hare expansion and land banking around Peotone for a potential third airport. Still, its membership comprises the city's top business leaders, so even the suggestion by that group of a possible south suburban airport could be considered good news for Peotone backers.

The other major boost for the Peotone proposal was the election of George Ryan. The new governor pledged during his campaign to spend $20 million purchasing land in the Peotone area. By law, the state must approve any new runways or airports in Illinois, if any federal or state money is used for construction. If the legislature appropriates the money for the land, that will send a signal to potential airline tenants, says Robert L. Donahue of Aviation Associates Inc. The state retained the firm to seek airlines that would commit to a third airport.

"Once you begin land banking, you'll see airlines come forward. There are domestic airlines that said, 'We can't commit to opening day, but we'll be there the first year,'" says Donahue. He adds that some foreign airlines have also expressed interest in Peotone.

There have been developments in Washington, D.C., too, over the past couple of months. Though busy chairing impeachment hearings, U.S. Rep. Hyde took time to organize a task force of his colleagues to discuss airport growth. The Illinoisan, who represents the communities surrounding O'Hare and is a vehement expansion opponent,

26 / January 1999 Illinois Issues

sent a letter to

a bipartisan contingent of representatives from districts near New York's La Guardia and Kennedy airports and Ronald Reagan National Airport in Washington, D.C.

These four airports share a federal limit on the number of landing and takeoff slots they can offer airlines. When Hyde got wind of a move to increase those slots, he did some quick maneuvering to hold any additions to a minimum.

As for federal action on a third airport, the Federal Aviation Administration must still pass on the environmental issues raised by the Peotone proposal. That decision could take another year. In the meantime, the Democratic Clinton Administration is unlikely to overrule a Democratic mayor's objections to the site.

Sitting out the recent fuss are the airlines, specifically Ft. Worth, Texas-based American Airlines and United Airlines, headquartered in Elk Grove Township. Together, they control more than 85 percent of the prized landing and takeoff slots at O'Hare, according to a U.S. General Accounting Office report.

Though quiet for now, however, the airlines have made it clear they have no interest in investing money in another large airport so near O'Hare. Doing so would force them to compete against themselves and cannibalize their O'Hare operations, they say. United claims about 40 percent of the landing slots at O'Hare and spends about $100 million annually on landing fees and rental space, according to a spokesman. It also spent $500 million on a new O'Hare terminal about 10 years ago. American has about 45 percent of the landing slots at O'Hare. A spokeswoman says American has spent about $500 million at O'Hare in the last decade.

"The airlines pay for airports by paying rent, landing fees, passenger charges and by backing general aviation revenue bonds," says Mary Frances Fagan of American. "There is not a tax dollar that is used to operate O'Hare."

At Midway, the new player is upstart Southwest Airlines, which has said it wants nothing to do with Peotone. The Dallas, Texas-based airline recently pledged to spend $760 million at Midway through 2012.

Last month, Ryan and Daley got together for a post-election powwow, and the subject of airports was raised. But, though the two are likely to have more cordial relations than the mayor had with outgoing Gov. Jim Edgar, Ryan and Daley will have their hands full with other matters in the near future. Daley is running for re-election; Ryan is setting up a new administration.

Nevertheless, the Metropolitan Planning Council is working to play a part in any negotiations. The non-partisan Chicago-based interest group works on growth-related issues, including transportation and is preparing recommendations for an aviation planning process.

"We want to find common ground and determine if we can agree on a regional approach," says MarySue Barrett, president of the council. "Daley and Ryan could take some important first steps. They should be open-minded and agree on a representational panel."

Such a panel could include the airlines, state and federal regulators, and the city, but Barrett says perhaps others could sit in too.

"We purposely have not sought a specific set composition to the panel. But anyone who thinks there should be no growth at O'Hare and Peotone should be built now is probably not going to work," says Barrett.

Major items of discussion might include reconfiguration of O'Hare runways, the impact of technology

improvements, land banking, air safety and noise, according to Barrett.

If something is going to happen, it probably should be soon. Experts say that even if ground were broken today at Peotone, it would be several years before a single plane lands there.

And the competition is moving forward. Dallas International Airport recently completed a $295 million makeover, and officials plan to spend $5.5 billion on renovations over the next 20 years. Denver caught flak for closing its Stapleton Airport and building a brand new facility, which became the butt of national jokes for its screwups with luggage and other problems. But that appears to have been worked out, and United has increased its flights there. Denver and Dallas have already begun using the technology that allows for more efficient landings.

This combination of competitive pressure, a new governor and projections of growth in the number of passengers could get all parties moving on an airport decision.

At least one thing is certain, notes John Geils, chairman of the pro-third airport Suburban O'Hare Commission: "Last time I looked, there is not any more airspace."

Illinois Issues January 1999 / 27