Trends

FINDING NEW WAYS TO HELP

Two state agencies have launched programs to encourage local support networks

GRANDPARENTS AS PARENTS

Sending seed money to local support groups

by Maureen F. McKinney

When Pieretta Smith brought 9-month-old Rodney into her home in 1994, not only did her life become more hectic, it represented an increasingly prevalent social phenomenon:

grandparents raising grandchildren.

"I'm doing things I hadn't planned to," says the 51-year-old Springfield parent educator, whose youngest child is now 27. "It isn't that I wanted to do it again; I had to." She says she chose to raise Rodney because she believed the child was being neglected by his parents her now-33-year-old son and a girlfriend.

But Pieretta Smith is not alone among middle-aged Americans in making the decision to raise a second family.

Between 1970 and 1997, the number of American children being raised in a grandparent-headed household climbed by 76 percent, according to the March 1997 U.S. Census Population Survey. That surge means that 5 percent of children 3.9 million live in a grandparent-headed home, according to the census survey. And 1.4 million of those children are being raised by grandparents without a parent in the household.

In Illinois, officials estimate that at least 70,000 children are being raised by grandparents or other relatives instead of their parents. And the director of Illinois' Department on Aging, Maralee I. Lindley, says she believes the number is likely much higher. Indeed, while the department has been unable to collect hard numbers, anecdotal evidence of a

growing incidence of grandparent-headed families was strong enough to spur the agency into action. Throughout the state, people who work with children such as educators, nurses and social workers have witnessed an increasing number of grandparents functioning as parents, Lindley says. And for the first time this fiscal year, the agency sought and won $120,000 to award grants for local support groups and pay the salary of a program coordinator to deal with the issues that arise when grandparents take on parenthood a second time.

The trend is likely a consequence of such social problems as drug abuse and teen pregnancy, says Barbara Schwartz, the department's new grandparents-as-parents program coordinator. Neglect. Abuse. AIDS. Mental illness. The death or imprisonment of the parents. These are frequently the reasons children are driven into the safety of a grandparent's arms.

And often, those grandparents are traumatized as well.

"It is a family in conflict," says Schwartz, who joined the agency in July. "One grandparent said, 'The stakes are very high. Do I go to court and have my children declared unfit and risk losing my grandchildren and my child?'" And, Lindley adds, "Many times the grandparents fear for the lives of these children."

That was the case for Smith. She made the decision to take her grandson from his parents' home after returning from a week-long trip to learn that her son wanted her to take baby Rodney for yet another weekend. The request was the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back. Rodney's home life, she says, started with parents who stayed out all night and slept all day. His

mother's two older children often did not make their way out of pajamas and into clothing, Smith says. "Even when I lowered my standards, his basic needs were not being met."

"Drugs were an issue," she acknowledges.

Smith says she sat down and wrote Rodney's parents a letter asking that they let her raise him. In three weeks, she brought him to live with her. Along with the child came a new set of challenges: finding child care and learning to live with little sleep. She had to accept that her life had changed drastically.

"I had planned on having a leisurely life and traveling and loving grandkids, but not keeping them," she says.

At 51, Smith is a bit younger than the average grandparent-as-parent in Illinois. In 1996, the Department on Aging surveyed 356 grandparents raising grandchildren throughout the state and found that 69 percent of them are over the age of 51. One suburban social worker says she works with grandparents acting as parents who are between the ages of 42 and 72. Nationally, the median age is 57. According to the department's survey, 50 percent of the grandparents were on a fixed income; 35 percent had incomes under $14,999, but 10 percent made more than $50,000 a year. Among respondents, 81 percent were female.

Smith says she realized initially that she was far from alone in her struggle, but she believed the situation was largely one affecting African Americans in urban areas. Her membership in a support group has shown her that grandparents raising grandchildren come from differing socioeconomic backgrounds.

In fact, one of the first support groups in the state began in affluent, suburban

28 / January 1999 Illinois Issues

DuPage County. A few grandparents were meeting at the end of 1992, and the group drew 24 grandparents by early 1993, says the group's facilitator Anne Zeidman, a social worker with Metropolitan Family Services of DuPage. "Up until the early '90s no one defined it as a problem that cut across society," Zeidman says.

One of the big challenges is to assure grandparents that they are not abnormal, and that it is acceptable to seek help, Zeidman says. "There are lots of grandparents who don't want to publicly announce they are raising their grandchildren," she says. "We encourage grandparents to come forward. They usually feel very isolated and unique. The challenge is to make the public aware that there are lots of people in this situation."

The Department on Aging saw support groups as a way it could help grandparents, Lindley says. "We knew in Illinois this was a large population. This is one of the few things we can do to help." Thirty-nine grants of $1,000 or $2,000 were awarded this year through the support group network.

Few of Smith's friends have children at home, so the support group she attends has served as a wonderful social outlet, she says. "So often the grandparents are isolated," says Schwartz. "They can't do things with friends." Smith says, "When I first went there it was to gather information. When I got there, I enjoyed it so much. It's a group of friends, now."

Bringing a child into a family especially one with a fixed income raises financial issues. When federal welfare laws changed in 1996, Lindley says, the department tried to ensure that grandparents who are raising children were not adversely affected. Consequently, Illinois awards

financial support to grandparents who are raising grandchildren regardless of their income level, Lindley notes. Still, many grandparents are reluctant to seek help, Lindley says.

There are other problems, as well, for grandparents who end up raising their kids' kids. The legal system, for one. "One of the things that happens is that they wind up in a court of law, and they've had no supportive help along the way," Lindley says.

Though these grandparents have many problems to worry about, such as their own health and legal issues related to custody, the number one issue is education, Lindley says. "It [the department's survey] was really very illuminating."

Smith is proud of Rodney, who is now a kindergartner. "One good thing is he's doing so well in school. He's doing excellent work."

Though Lindley says she's seen sorrow plaguing the grandparents, they all manage to find some joy in the way their lives have shaped up.

"It's heartbreaking. But then I will see a bright shiny smile, and they tell me, There is no way I wouldn't do this.' They tell us they are energized." Lindley says it's happening because these grandparents want to do this.

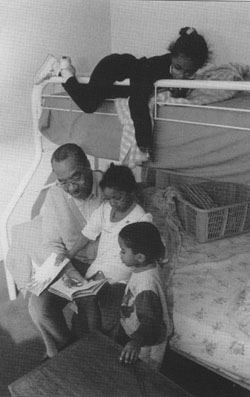

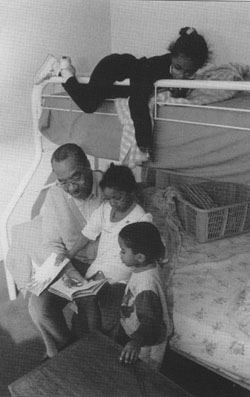

"I would not trade a minute of it," says 70-year-old retiree Rudy Davenport of Springfield, who helps I his wife raise her three grandchildren.

"You are reaching at a higher level to do something for someone outside yourself I someone who is desperately needy." Davenport was engaged to the three children's grandmother when they became wards of the court in Pennsylvania two and half years ago. The parents had been charged with neglect.

"I'm quite attached," says Davenport, whom the children call Papa. "I love them dearly."

|

His life is much different from what he might have anticipated.

"You can remember that day when you could do things you wanted to do like volunteer work. But everything is about meeting their needs," says Davenport, whose daughter from a previous marriage is 42. "Time is very precious."

It would be easy for these grandparents to be bitter, but they are not. "Sometimes you might be resentful," says Smith. "We've been doing this so long, it's routine. It's normal to us. There's no time for resentment," she says. "Life's too short."

|

Rudy Davenport of Springfield helps his wife raise her three grandchildren, Azaliah Isaiah, 7, on the top bunk, Rahab Isaiah 5, and Jonah Isaiah, 3. "I would not trade a minute of it," says the 70-year-old retiree. "I'm quite attached." His life is different from what he would have anticipated. "You can remember that day when you could do things you wanted to do like volunteer. Everything is about meeting their needs."

|

Illinois Issues January 1999 / 29