FROM RAIL YARDS TO IVY HALLS

Old-style unionism may have faltered. But the past

could give rise to new strategies for labor

Review essay by Burney Simpson

THE PULLMAN STRIKE AND THE CRISIS OF THE 1890s:

ESSAYS ON LABOR AND POLITICS

Edited by Richard Schneirov, Shelton Stromquist and Nick Salvatore, 1999

University of Illinois Press

THE SECRET LIVES OF CITIZENS:

PURSUING THE PROMISE OF AMERICAN LIFE

Thomas Geoghegan, 1998

Pantheon Books

HIGH-TECH BETRAYAL:

WORKING AND ORGANIZING ON THE SHOP FLOOR

Victor G. Devinatz, 1999

Michigan State University Press

ACADEMIC KEYWORDS:

A DEVIL'S DICTIONARY FOR HIGHER EDUCATION

Cary Nelson and Stephen Watt, 1999

Rout ledge

The classic boxer pose is head-on,

crouched, arms up, legs tensed,

moving forward. It's aggressive and

challenging. There is something very

American about the pose: I will come

to you and fight you and I will win.

Some 50 years ago, boxing was one

of the most popular sports in the

country. People knew the names of

the champs of half a dozen weight

divisions. They knew the top contenders, too. But the fight game

began to take its fans for granted, and

raw brutality fell from favor.

The American labor movement

peaked around the same time. In the

early 1950s, union membership

included 42 percent of manufacturing

workers and 87 percent of those in

construction trades. In 1954, 35

percent of American workers were

union members. Labor was an

aggressive movement that won the

eight-hour day. It picked fights and

won victories. In 1946, the United

Mine Workers took a giant step and

won health and pension benefits. In

1950, the United Auto Workers

struck Chrysler for 100 days and

won a $100-a-month pension,

unprecedented in its day. A new

middle class was born.

It's been downhill since.

As paychecks got better, union

leaders began to resemble management. The cars, cigars and waistlines

got bigger. The rank-and-file got

complacent, too. Hard-won benefits

were taken for granted. Then Jimmy

Hoffa denied ties to organized crime

in televised testimony to Congress. A

few years later he was in prison. Then

he disappeared.

Questionable friends, a stodgy

image and short-term thinking left

Illinois Issues September 1999 29

unions flat-footed as America shifted

from a manufacturing to a service

economy. And though a leading union

such as the Service Employees International Union jacked its organizing

budget up from $20 million in 1995 to

$60 million in 1998, the unionized

share of the workforce — 14 percent in

1998 —continues to lag.

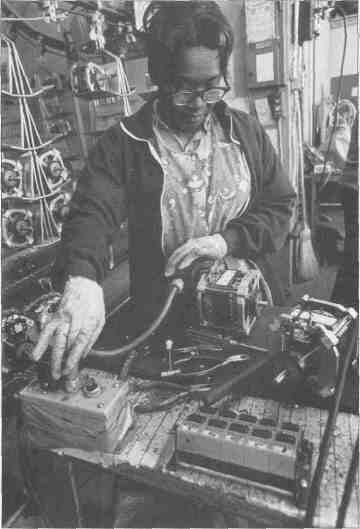

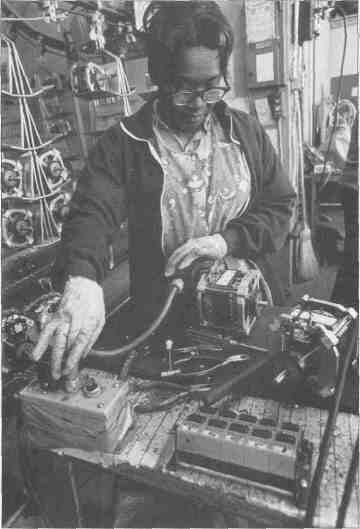

General Electric,Dekalb.

|

Several recent books on the history

of labor and the rise and fall of

unionism suggest a few new strategies. First, unions cannot thrive if

they remain nearly all-white, all-male enclaves. And second, while they

move more aggressively to hang on to

their base, unions will need to move

beyond the traditional steel, auto and

rubber trades.

These are interesting times for those

who would organize — or reorganize

—American workers. Indeed, union

shops may soon encompass such

diverse workplaces as Silicon Valley

chip plants and university faculty

lounges. Two events this past summer

illustrate the point. While six old-line

textile plants in North Carolina were

voting to unionize, the American

Medical Association was approving a

call to doctors to consider unionizing.

After all, it argued, these days many

docs are just employees of HMOs.

At the same time, aggressive

organizing by the Service Employees

International, which represents such

workers as nurses, hospital and health

care aides, public employees and

janitors, managed to boost that

union's membership by 64,000 in

four years through 1998.

And mainline unions are openly

flexing political muscle again. The

AFL-CIO backed President Bill

Clinton — and backed that support

with campaign dollars and foot

soldiers. Further, union officials are

considering new ways to capitalize on

their 16 million members nationwide.

One idea: Enlist members as enumerators for the 2000 Census on the

theory that a more accurate count in

minority and working class neighborhoods could mean more federal

dollars for those communities where

much of the membership lives.

|

But as unions search for ways to

rebuild membership and influence,

they might reconsider some past

mistakes. The Pullman Strike and the

Crisis of the 1890s: Essays on Labor

and Politics, a collection edited by

Richard Schneirov, Shelton

Stromquist and Nick Salvatore that

details a turning point in union

history, offers a few lessons. Though

the 1894 strike against the Pullman

Car Works in Chicago failed, it led to

gains in union organizing nationwide,

brought widespread public support to

the labor movement and gave one of

its leaders, Eugene Debs, a platform

to run for president. The strikers did

much that was right to bring most of

the nation's rail traffic to a halt. But

they made some serious miscalculations, a result of their own small-mindedness, or management manipulation.

Pullman was the quintessential company town. George Pullman, an industrialist railroad sleeping car builder,

designed it to be a social experiment,

with clean streets, parks, stores and

homes with indoor plumbing.

Pullman offered better pay than his

30 September 1999 Illinois Issues

competitors, too. But he wasn't

altruistic. He built his town several

miles south of downtown Chicago to

keep workers away from union influence. And because the company

owned everything, workers'

paychecks kept flowing back in rent

payments and grocery charges.

Pullman's company also had a ready

supply of cheap, eager labor in the

largest influx of immigrants to that

point. A census taken in 1892 found the

workforce at the Pullman plant was

nearly 70 percent immigrant, mostly

from the Scandinavian countries,

Germany and other parts of Europe.

Many spoke only the language of

their homelands and knew little if any

English, management's tongue. It was

easy for Pullman and his foremen to

use this barrier to make his workers suspicious of one another by giving favored

ethnic groups bonuses or promotions.

But as dissatisfaction with working

conditions at the plant grew, the

common struggle to survive in a

strange new country helped draw the

workers together.

By 1885, individual craft unions

had been formed at Pullman by car

builders, cabinetmakers and blacksmiths. Some of these smaller unions

conducted strikes. Still, no single

event drew the groups together until

the Depression of 1893 spread to the

Midwest. Pullman decided to fire

some workers and cut wages by a

third without lowering rents or food

prices. And the crafts, under the

national umbrella of the American

Railway Union, went on strike.

The walkout continued for most of

the summer of 1894. At its peak it

shut down rail shipping from Illinois

to the West Coast. Eventually,

President Grover Cleveland, siding

with management, sent troops to

break up disturbances. This allowed

replacement workers to come and go

without fear of retribution. The strike

was broken.

Nevertheless, the action at Pullman

was successful in several ways. It

brought together workers from across

much of the country, many of them

foreign-born. The public supported

the strikers, too, at least until reports

of union vandalism and violence. In

1898, Congress authorized unionization of rail workers. And within the

next decade membership in trade

unions tripled.

But the strike also made clear a

deep division between the virtually

all-white American Railway Union

and the black Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union. The ingrained

racism in the American Railway

Union meant blacks were kept from

joining. And when the strike began,

the porters refused to walk. This was

a tough blow because it meant the

railroads would continue running in

the East. Pullman managed to further

inflame these tensions by bringing in

blacks as replacement workers.

It took another 30 years for railway

unions to make progress in opening

up membership to blacks.

Racial and ethnic tension has

long plagued the larger labor movement. And such divisions can still

determine whether a factory will go

union, a central point in High-Tech

Betrayal: Working and Organizing on

the Shop Floor, an account of a shortlived attempt to organize a medical

equipment factory in 1983 on Chicago's North Side. Author Victor

Devinatz, an associate professor of

management at Illinois State University in Normal, dropped out of

graduate school to work at the

assembly plant. A major theme of his

book is workers' inability to cross the

boundaries of race and ethnicity.

Devinatz idealistically hoped to

organize in a growing industry that

unions had ignored. But he soon found

himself in a multiethnic stew of

distrust. He ties that distrust to Chicago's mayoral election that year.

Harold Washington went on to

become the city's first black mayor,

and history has smiled on his legacy.

But during the campaign, the atmosphere in city and factory was anything but happy. Racist pamphlets

and graffiti were common. Washington's white opponent used the theme,

"Before it's too late." Devinatz recalls

he was the only white person at the

plant to wear a Washington campaign

button.

Unlike Pullman's workers, these

workers — mostly blacks, Latinos

and Asian immigrants — pulled away

from each other. Skin color proved to

be a tougher barrier to cross than

language differences.

The time was ripe for Washington's

victory, but the timing was wrong for

Devinatz. When he attempted to form

a core group of black and Latino

organizers, a black co-worker

informed management. The owners

contrived to fire Devinatz and the

co-worker ended up with his job. To

his dismay, Devinatz' Latino friends

told him later he should never have

trusted the black worker.

During his seven months at the

factory, Devinatz would try to plant the

union seed during casual conversations.

But few wanted to listen. Again, his

timing was unfortunate. Worker

complacency was running high. The

children and grandchildren of those

who had won the great union victories

took working conditions for granted.

Devinatz writes of one: "Sam's comments did not seem atypical of those of

many American workers — reflecting

an almost complete lack of a trade

union consciousness or any kind of a

working class consciousness."

Devinatz's efforts may have been

unsuccessful, but he has to be judged in

the context of the day. The biggest

unions were still clinging to the steel

and rubber plants, while those industries were moving overseas. Workers in

minimum-wage factory and warehouse

jobs, and in the growing service sector,

weren't considered worth the effort.

Meanwhile, "Reagan Democrats"

helped elect a Republican president

who allowed nonunion workers

to replace the striking air traffic

controllers. Whatever union solidarity

remained failed to cancel flights.

A destructive cycle had set in for

the union movement. It had lost its

ability to bring workers together, or

to demonstrate that it offered more

than white-collar workers were

already getting from management.

Few workers would look beyond personal gain to collective power.

After bottoming out in the 1980s,

can unions regain their strength? Two

other recent books by Illinois-based

authors try to point the way. One

Illinois Issues September 1999 31

considers the future while the other

takes a nostalgic look back.

In his The Secret Lives of Citizens:

Pursuing the Promise of American

Life, labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan calls for a return to the progressive values of the 1930s New Deal,

and a strong federal government that

'will give labor a prominent place at

the table. But Geoghegan, who

worked for President Jimmy Carter's

administration in Washington before

moving to Chicago in the early 1980s,

offers this critique: The great problem

of the New Deal was that it didn't

include the South. In return for

support early in his administration by

Southern legislators. President

Franklin Roosevelt allowed the

region to remain union free. Labor

has been hurt ever since, according to

Geoghegan.

To save money, businesses moved

south and workers followed. Population

growth meant more legislative power in

Washington, D.C., for conservative

states. Pro-business politics, Geoghegan

argues, enabled Reagan to overhaul the

National Labor Relations Board and his

successor. Bill Clinton, to push passage

of the North American Free Trade

Agreement against labor's wishes.

But Geoghegan's fixation on the

South's rise as the cause of every step

backward in the struggle between

labor and management wears thin.

(He goes so far as to wish the Civil

War hadn't been fought to keep that

region in the union.) Wringing hands

over the losses of yesteryear won't get

more votes or build a union local.

What purpose can it serve to write off

a third of the country, especially

when that region continues to grow?

And it raises another question: Are

progressives doomed to repeat the

mistake they made when they ignored

the decline of the manufacturing

sector? One of the strengths of

today's union leadership is the ability

to see, or at least pretend to see,

the South as an area filled with a

thousand organizing possibilities.

Ending on a hopeful note, Geoghegan gives an account of a meeting

near Chicago of labor and a multicultural, multiethnic, multireligious mix

of activists. The coalition, designed

to cross racial and class lines and the

borders of city and suburb, seeks to

find a common response to problems

in the area. The spirit is still there,

writes Geoghegan. At least north of

the Mason-Dixon line.

Authors Cary Nelson and Stephen

Watt are more forward-looking. Academic Keywords: A Devil's Dictionary

for Higher Education argues universities present an opportunity for union

organizers. Their book takes a broad

look at the current state of academe,

but includes several chapters on

|

THE UNDERGROUND LABOR FORCE

One small-time southern Illinois hood managed to earn

notoriety and a noose while working from home

Review by Burney Simpson

A KNIGHT OF ANOTHER SORT:

PROHIBITION DAYS AND CHARLIE BIRGER

Gary DeNeal, 1998

Southern Illinois University Press

The image of the Illinois gangster is that of a gunman

fighting for control in Chicago. During Prohibition,

Al Capone and Bugs Moran made headlines selling

liquor. Today, the 10 o'clock news likely leads with video of a

lifeless teenager, allegedly a crack dealer, sprawled beneath a

stained sheet on one of that city's street corners.

But Chicago has never had a lock on bad guys willing to

make a buck selling goods and services off-limits to the law

abiding.

Charlie Birger was a murderer, thief, pimp and bootlegger

in southern Illinois who provided much comfort to the

businessmen, coal miners and farmers of Williamson,

Franklin and Saline counties during the first quarter of this

century. His Shady Rest resort was a favored spot for illegal

drink and bets on fighting dogs.

Actually, the resort, midway between Harrisburg and

Marion, was just a dressed-up log cabin with a roadside

barbecue stand as a front. If Birger ever earned an honest

day's pay, he supplemented it with more lucrative work.

Gary DeNeal's A King of Another Sort: Prohibition Days

and Charlie Birger chronicles this small-time hood's sordid

but fascinating life. Southern Illinois Press published this

second edition, with new photos and other material, last

year. DeNeal's research is extensive and the writing is hardnosed, colorful, and occasionally humorous.

Birger's reputation for violent retribution was powerful,

so much so that several of DeNeal's sources requested

anonymity 70-some years after the gangster's death. But

|

32 September 1999 Illinois Issues

|

Birger also developed a reputation as a rural Robin Hood,

giving away groceries and cash to folks down on their luck.

And — a cost of doing business — he befriended local law

enforcement, either with tips on the whereabouts of rival

criminals, or with payoffs and services at his resort.

|

Sothern Illinois bootlegger Charlie Birger(center,sitting

on car roof) and his gang at their roadhouse,Shady

Rest, in "Bloody Williamson" County in 1927.

|

Along with the friendships, though, came enemies. First

in the form of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization of local

businessmen and

political leaders who

grew tired of the

corruption. The Klan

quickly mounted successful raids on bootlegging operations.

Soon, these

vigilantes got out of

hand, too. In 1924, a

shootout in downtown Herrin between

factions of the Klan

and the gangs left six

dead and helped

cement the national

reputation of

"Bloody Williamson" County.

Birger denied

involvement and was

never brought to trial. And the Klan was effectively finished as a public

organization.

But Birger's most enduring enemies were his business

rivals. He began fortifying, leveling trees surrounding his

cabin to keep a better eye on those who might try to sneak

up. Members of the Shelton gang responded by using a

single engine plane to drop three homemade bombs near the resort. Two were duds, but a third

exploded, purportedly killing an eagle and

Birger's pet bulldog.

|

The gang wars

inevitably escalated

and Birger eventually

was convicted for the

murder of the mayor

of West City. According to DeNeal,

though, the gangster

was responsible for

committing or

ordering the murder

of many others.

In 1928, Charlie

Birger was led to the

gallows in Benton. He

wore a suit made by

Al Capone's tailor.

|

unionizing white-collar workers on

campus.

Nelson and Watt contend that

graduate students should be

organized because they are doing

more of the teaching at colleges and

universities. They compare today's

university towns to the Pullmans of

old, with a single employer controlling the jobs and salaries of most of

the residents. While tenured professors do more research, schools

require graduate students to teach

such nuts-and-bolts classes as freshman composition.

Further, such courses have become

profit centers for colleges, according to

Nelson, a professor of English at the

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Because virtually all undergrads

must take composition, the barely

minimum-wage grad student is teaching 200-plus students at a time. The

return on expenses this represents for

big universities helps pay the ever-

increasing salary of the full-time

research prof in a smaller discipline

such as agriculture. The authors

estimate the school makes $8,000

for each composition class taught by a

grad student.

These academics present a strong

argument for labor in the nontraditional halls of ivy. In fact, the United Auto

Workers has already begun signing

grad students at Yale and the Big 10

universities of Wisconsin, Michigan

and Iowa. Nelson argues the next

challenge is the growing number of

part-time teachers.

More than 100 years after the

Pullman strike, labor is at another

turning point. But those who want to

relive past glories might remember

the slow decline of the greatest boxer

ever, Muhammad Ali.

As the years wore on and the legs

lost speed, Ali resorted to a style of

fighting he called "Rope-A-Dope."

The idea was pretty simple: Imitate

a spider. He would hang in a corner

with his back against the ropes,

almost still (except for the occasional

stutter step for the crowd), and wait

for the latest hopeful to come to him.

After a few rounds, the energetic

contender would be frustrated and

tired from trying to get the stubborn

Ali into the center of the ring. For a

second or two, the challenger would

lose his concentration and let his

arms down. Suddenly, the Ali of

bygone days returned. He pounced on

the guy, the punches connected, and

the startled challenger backpeddled,

swung, missed, tripped. There was

still enough there to put the dazed

youngster away. But Rope-A-Dope

only tricked them for a few fights.

The young guys caught on.

A reactive strategy never works

for long. Pretty soon, a fighter has

to get out there and throw some

punches.

Illinois Issues September 1999 33