24 / November 1999 Illinois Issues

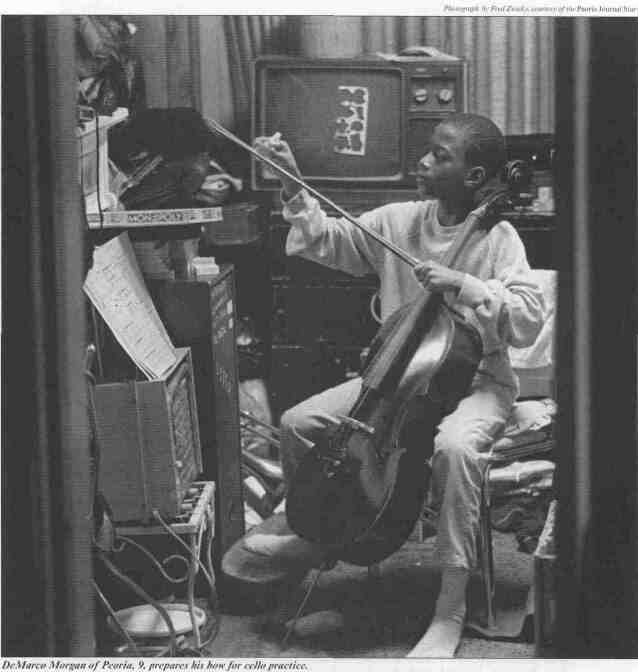

No time to be a kid

Our children don't play freeze tag anymore.

There's no time between baseball and ballet.

And the kids are paying the price

By Jennifer Davis

The schooners, the waves, the clouds,

the flying sea crow, the fragrance

of saltmarsh and mud, the horizon's edge.

These become part of that child who

went forth everyday

And who now goes and will

always go forth everyday.

from Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass

Walt Whitman's verse no longer

has relevance to our lives. Our

time for the soul is lost, surrendered to

the phrase "You've Got Mail" or

drowned in the raucous lights and

music at Chuck E. Cheese. The drive

from soccer practice to ballet is not

long enough to ponder.

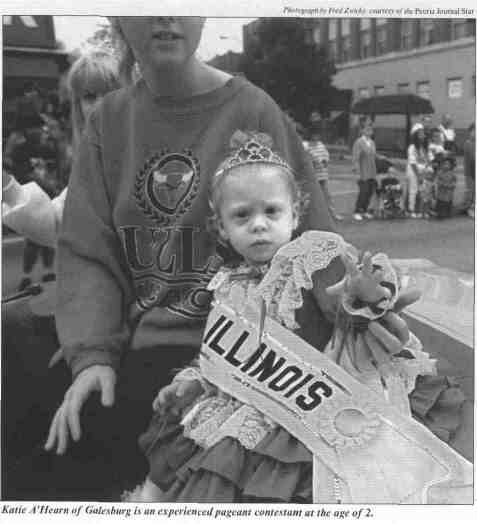

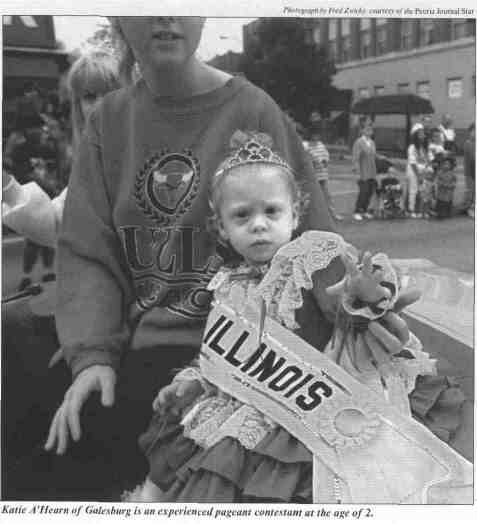

We have no time to think, let alone

absorb nature's beauty or play a

spontaneous game. There are 2-year-olds to prep for prep school, after all.

Wait a minute. A growing number of

psychologists (psyche being Greek for

the soul) are warning us to heed a childhood chant: Stop. Look. Listen. Does

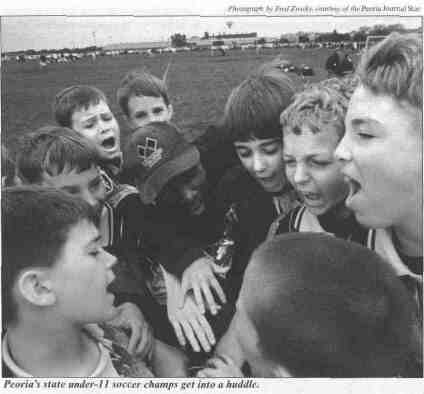

your 10-year-old really need soccer,

hockey, piano and drawing? Maybe not.

They warn the price of all these activities

may be stressed out, overscheduled kids.

Not only famous children such as

tennis star Jennifer Capriati, who turned

pro 24 days before her 14th birthday suffer this fate. Psychologist Sheila

Ribordy treated an 8-year-old who

thought his parents had enrolled him in

so many activities to avoid spending

time with him. "They definitely had the

best of intentions," says Ribordy, director of the clinical psychology training

program at DePaul University in Chicago, of the parents.

Why would well-meaning parents

cause a child heartache? Because the

problem runs deeper than individual

parents. Society encourages this overbooking of our kids. "We are going

through one of those periods in history, such as the early decades of the

Industrial Revolution, when children

are the unwilling victims of societal

upheaval and change," writes David

Elkind, a professor of child development at Tufts University and author

of The Hurried Child: Growing Up Too

Fast Too Soon.

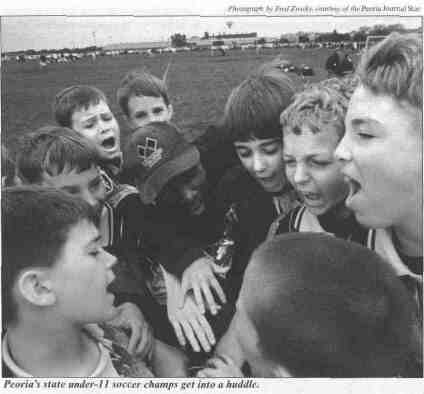

Our children don't play freeze tag anymore. And they don't ride bikes around

the neighborhood like they used to;

instead, they go to soccer and ballet and

computer camp. The activities themselves are not bad. But often as parents

we push our children. Do more. Learn

more. Excel more. They go to camp at

the expense of spending a Thoreau-like

summer in their backyards.

Part of the reason we do this is that

the traditional family, which we might

equate with homemade sit-down dinners

and Sundays in church, has evolved

beyond the 1950s. June Cleaver is now a

soccer mom. No single image of the

modern family single-parent,

divorced, blended, two-income comes

to mind. Except, perhaps, a stressful

one.

Since the 1960s, when the family

dynamic started changing, society has

found itself following two styles of

child-rearing: that of Superparent

raising Superkid and that of the

stressed-out parent bypassing their kid's

childhood as a means of lightening the

load. Thus, the child who can start dinner can make dinner. Or the child who

can put away his clothes can do laundry

and so forth.

Further, our so-called latchkey kids

face not a demanding parent, but an

invisible one. An empty house. Mindless

television and video games for company.

Illinois Issues November 1999 / 25

Too much freedom, but no real time

for the soul.

Despite the tumultuous cultural

change, encouraging statistics have

emerged. In this decade, the nation's

rates of teenage births, violent juvenile

crime and teenage drug use have all

declined. However, at the beginning of

one of our most narcissistic, consumption-conscious decades, the '80s, Elkind,

rather prophetically, noted that our children were in trouble. In the '90s, reality

bore out his assertion in the form of

tragedies like Columbine.

We should not be surprised that our

children commit adult acts of violence

when we have made the mistake of

treating them like adults.

Elkind used the simple case of how

children spend their summers to illustrate his point that we rush maturity.

"The change in the programs of summer

camps reflects the new attitude that the

years of childhood are not to be frittered

away by engaging in activities merely for

fun," notes Elkind. "Rather, the years

are to be used to perfect skills and abilities that are the same as those of adults."

Mini-adults. That's what we're raising.

Not children. JonBenet Ramsey wore

|

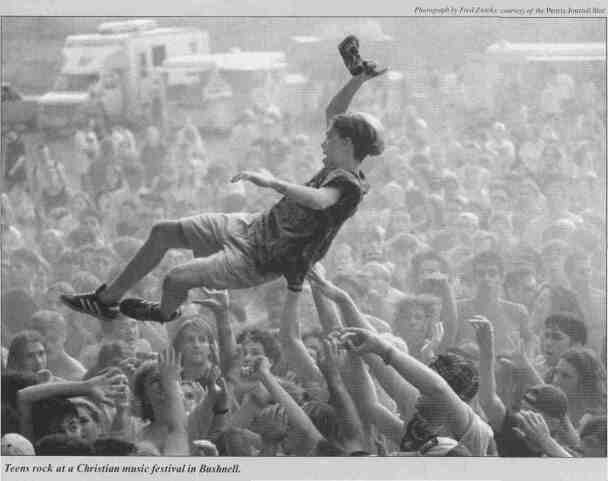

There's no single face on youth rebellion

By Josh Bluhm

A pallid-faced crowd dressed in black gathers outside

Chicago's Metro nightclub, and draws derisive shouts

from a passing car. "Hey, where's the funeral?" mocks 26-year-old goth David Birdwell of Chicago. For Birdwell and

other goths, such vocal abuse is almost a cliche. Yet, such a

casual approach reflects the attitude of alternative groups.

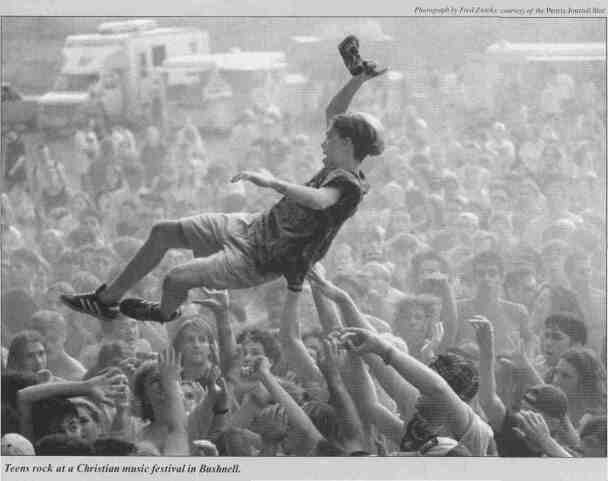

Hip-hop, gangsta, grunge, punk and hippie. The gothic

scene is one of myriad youth subcultures that have

emerged, or re-emerged, at a stunning pace in recent years.

This splintered face of alternative cultures is a result of the

electronic age. The explosion in Internet use has inundated

youth with information, and given them countless opportunities to experiment with identity In 1999, there's no one face to youth rebellion.

Of course, there's a side to youth subcultures that's timeless. Adolescents have always faced simultaneous and conflicting impulses: to identify with others and assert

individualism. The dissension between mainstream society

and subcultures, including the goths, sounds as if it comes

from 1960s revolutionary Tom Hayden's Justice in the

Streets'. "As the misfits of a dying capitalism, we were

repressed in unique ways and had to rebel in unique ways."

Though ways to rebel may have evolved, the reasons to

participate in subcultures remain a constant. "Youth

identify with subcultures because they are looking for a

home, looking for the thrill, the risk of being perceived as

dangerous," says Beth Doll, an expert on youth development and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Colorado. Young people are going through

rebellion and experimentation just as previous generations

did, but today's easy access to information widely expands

the experiences available to contemporary kids, says

Nanette Potee, a professor of intercultural communications

at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago. Such

communication barriers as time and space are shattered by

technology, and cultural distinctions between geographical

areas become more obscure.

Changes in the face of society have given room for the

computer to become a powerful influence. Many children

have both parents working, says Wheeling High School

social worker Tom Scotese. This tends to mean they look

more outside the family for identity. What they are discovering for themselves, through the infinite possibilities made available by computers, often defies easy categorization by

mainstream society.

"Youth today are more technology oriented, technology

driven. As a result, what used to be a huge division between

urban and suburban no longer exists," Potee says. "The

experience of the kids in the suburbs is, at times, not so

different from the kids in the city."

Potee calls the mosaic of youth groups "co-cultures,"

and Doll says teens may shift from one group to another.

Most subcultures are constantly in flux. Lacking any rigid

hierarchal structure, subgroups have a tendency to resist

definite labels. Any one subgroup may share features of

other groups.?

The goth scene is just one of the many subcultures that

have grown exponentially as a result of technological

advancements. Yet gothic remains a relatively loosely

defined concept. "It is difficult to say what is gothic," Bird-well says. "It is not, as portrayed by the media, an organized group with leaders. It is basically artists and creative people

who have decided not to follow the masses in letting television and fashion magazines tell them what is hip to wear this month." He adds, "We'd just rather go to the new Jekyll

and Hyde club, and laugh at the cheesy B movies and talking skeletons, than go to the ESPNzone."

Springfield Southeast High School teacher Joni Paige

says she has noticed that her students are dramatically

affected by the media images issuing from electronic

sources. She points to the response of her students in

the aftermath of the events last spring in Littleton.

"Students were just as confused and had just as many

questions about the images coming out of Columbine

|

26 / November 1999 Illinois Issues

mascara and lipstick, and babies toddle

about looking just like us in miniature

Baby Gap jeans.

This is the single most important

cultural change regarding children over

the last 30 years: our view of them.

Decades ago, pushing children too

soon was frowned upon, thus the phrase

"early ripe, early rot." Society's view of

how to best raise our children had

changed drastically from the first part of

the century when they were sent to work

in the mines and factories. But, in some

respects, we've come full circle. The

return to a race to adulthood started in

the '60s, with an outpouring of new

research promoting early childhood

learning. Tax-supported kindergartens

became the norm. Parents started to

believe that children could, indeed

should, do more, learn more, be exposed

to more.

This shift in the view of child competence has us pushing and scheduling

them more, lest we squander their precious early years when learning capacity

is at a peak. For single parents, the

added benefit is that it soothes their guilt

about exposing their children to more

adult responsibilities. Give them more

|

as everyone else." She adds, "They really were anxious

to talk about what was happening."

The universality of the computer-focused world, in

particular, with its diversity of images, provides young

people with a broader experience. But at times that can be

disorienting. Paige says, "These more intelligent kids

exhibit more disillusion."

And David Birdwell notes, "It is traumatic for kids to

grow up seeing adults in the media fighting, having

affairs; 'Just Do It' and 'Just Say No' on the same TV."

The contradictory messages contribute uncertainty to

the already unstable period of adolescence. And at times,

any form of identity the young develop represents, for

them, a sense of security amid the confusion.

Birdwell adds, "Many kids feel that they should be able

to wear black and pierce their nose, since it is so much

more tame than what their parents were doing when they

were that age. "

|

Illinois Issues November 1999 / 27

because they can handle it. It's good for

preteens to come home to an emptyhouse every night and fix themselvesdinner. It teaches self-reliance, parenting articles argue.

And we, with our e-mail and faxes

and other immediate technogratifications, are so used to squeezingevery productive moment from everyday that we do the same for our children. With the best of intentions, ofcourse.

Certainly, Stefano Capriati hadthe best of intentions when he sent

his adolescent daughter out on the

professional tennis circuit. But he could not ignore his daughter's

breakdown at a U.S. Open press conference last September. In front ofthe microphones and cameras,

Capriati dissolved and, as one reporter put it, mourned "her

ransomed childhood." Speaking ofher shoplifting and drug use, she

said she took "a path of quiet rebellion, of a little experimentation of a darker side of my confusion in a

confusing world, lost in the midst offinding my identity."

We rush our children from soccer to piano, let them play video games at hyperspeed and then wonder why record numbers of children need Ritalin to sit still in school. Entertain them every second, build them a $5 million Disney-style day care in suburbanChicago complete with scaled-down tennis courts and then question teachers who complain that they are seeing more and more passive learners.

It's not a stretch to think that recent school shootings nationwideare our children's cry for help. Troubled teens won't all rebel quietly as Capriati did and then poetically explain their actions.

The fractured family structure, which has gone from being the exception tothe norm over the last 30 years, relieson this new view of child rearing:

Children don't need to be sheltered or nurtured '50s-style; there's just no timefor it in the '90s.

Jennifer Davis, a reporter for the PeoriaJournal Star, is a former Statehouse bureau chief for Illinois Issues and the mother of 5-year-old Drew Scott, whom she takes to hockey and soccer practices.

|

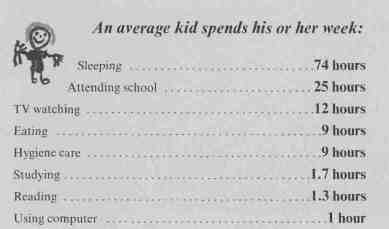

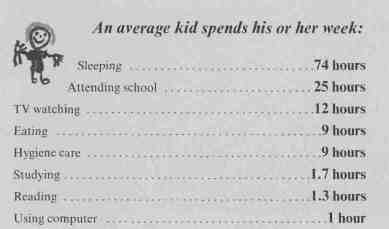

Playing soccer, baseball, hockey, basketball, football, volleyball; taking gymnastics, swimming, Tae Kwon Do, art, drama and music lessons;

talking on the phone; spending family time; fighting with siblings; doing chores; observing religion; putting puzzles together, playing games, building sand castles; flying kites, riding bikes, climbing trees, swinging and sliding, drawing pictures and playing video games; skateboarding,rollerblading; going to parties and club meetings; hanging out and other stuff ....................................50 hours

|

Source: Healthy Environments. Healthy Children: Children in Families,

a 1998 study by the University of Michigan, based on 3,586 participants under the age of 13.

28 / November 1999 Illinois Issues

Illinois Issues November 1999 / 29