Wherever the customer has the money and the developer has the land, the automobile subdivision is the preferred form of American residential neighborhood.

The string of middle-class one-family houses centered on their own lots, usually facing a curving street or cul-de-sac, is a mass-produced version of an urban form invented in the 19th century for the well-to-do. As built in Park Forest in the 1950s, the subdivision was the home of William H. Whyte's Organization Man; as built in the 1990s in places like Naperville — soon to be Illinois' No. 2 city, it consists of hardly any other type of neighborhood — it is home to dual-income strivers, the kinds of places where, as the Chicago Tribune's Merrill Goozner put it (with some exaggeration) in 1998, "preteens have five-minute standup breakfasts with their parents in a huge, country-style kitchen before mom rushes off to a sales meeting in Cancun; and where the kids get their computerized carpool schedules posted on the refrigerator door."

Yet the subdivision's popularity can be explained by neither its beauty nor its efficiency. Rather, it is seen as a stable environment in which to nurture two investments dearest to the middle class — real estate equity and children. Even baby boomers, many of whom couldn't wait to escape when they were young themselves, have fled the apartment tower, the loft and the three-flat for the same kinds of neighborhoods so many of them knew as children. Nearly a whole generation grew up in those GI Bill plantations that seemed to sprout in every Illinois cornfield after 1945. Taking their cues from such social critics as sociologist David Reisman and Mad magazine, boomers grew up to condemn such neighborhoods as conformist, racist, dull. But once these alienated adolescents became uneasy new parents, they sought out a subdivision house the way a bear seeks out a comfy den when the snow flies.

Are subdivisions still good places to raise kids? Were they ever?

Compared to the insults of life in the high-rise project or the rural shack, the typical subdivision is heaven for kids. Read Voices for Illinois Children's Charter for Illinois Children, for example, and you will not find the abolition of the cul-de-sac on the group's list of urgent reforms. Still, all is not well, even in the more affluent versions of our national model neighborhood. Sally Helgesen spent three years interviewing women in and around Naperville for her 1998 book, Everyday Revolutionaries: Working Women and the Transformation of American Life. She describes a hell Of overscheduled, overcompetitive, overdependent children who, having been given all the advantages, were naturally miserable. Kids spend too much time alone with their computers and music or wrapped in embracing, unrelenting intimacy with parents; in either situation they are cocooned from the real world, which might counter their tendencies toward fantasy and self-absorption. The presence of the youth gang, that ultimate symbol of urban social collapse, shows that, in psychological terms, adolescents do not find the ghetto and the subdivision to be as distant as most parents do.

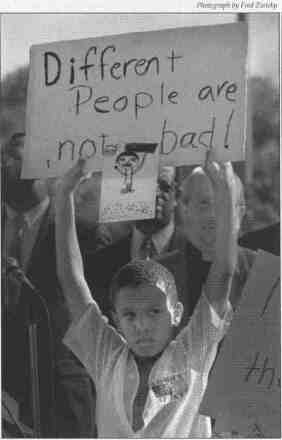

If critics of the '60s decried the class and racial isolation of the subdivision, today's critics point to the physical (and thus social) isolation imposed on children by the subdivision's physical form. In the National Review, Christopher Caldwell listed the layout of that "community" among the factors in the Littleton shootings, along with guns, TV, affluence, big schools, divorce, Hollywood, the Internet and goth music. That community's large house lots and the dead-end streets, he argued, doomed kids to a physical seclusion that precludes normal socialization. That seconds opinion from the left, voiced when Al Gore unveiled President Bill

30 / November 1999 Illinois Issues

Clinton's $1 billion-a-year "smart growth" program aimed at curbing the urban sprawl of which the subdivision is both symbol and advance guard. The vice president lamented that poor subdivision design has, among other ills, left suburban mothers isolated with small children far from playmates.

A fair accounting would attribute many of the benefits enjoyed by children to the fact that such neighborhoods are peopled by the middle class — not merely, mind, middle income people. And if the benefits of subdivision life cannot all be attributed to place, many of its problems can't be either. The freedom to explore is not constrained by kids' competence or even the world's dangers but by parents' anxiety. And of course kids can grow up healthy in the meanest streets, with help and

luck, and what happened in Littleton disabused people of the notion, if any still believed it, that material comforts inoculate the young against despair.

Still, if design is not destiny, neither is it wholly irrelevant. The subdivision's basic form is unchanged since the 1870s, when Olmsted's archtypical suburb was laid out in Riverside, outside Chicago. In terms of density, however, subdivisions are ever more attenuated. Old rules of thumb about what constitutes a "natural" community — the population defined by the distance a mom can comfortably push a baby carriage — are made nonsense by the low-density layout of the typical subdivision, which spreads a few destinations over a lot of space. Many a postwar bungalow project crammed 16 houses on a block 500 feet long;

today's McMansions boast driveways wider than the lots those earlier houses stood on.

Nor are those distances easy for children to navigate. The typical street layout minimizes traffic in front of most houses at the cost of concentrating it at one or two exit points on nearby "collector" streets, which form a roaring cataract of cars that even adults fear to cross. Studies of the new "walkable" housing developments have found that interior pedestrian and bike networks built for daily errands are seldom used for that by adults. The paths do serve as a substitute street system for kids. This is only a marginal improvement, unfortunately, because the paths connect only to the other parts of their own subdivisions. Kids are thus dependent on a car to get about, which makes them dependent on an adult to drive them. Older ones rightly resent having to ride every-

Illinois Issues November 1999 / 31

Protecting children, as distinct from teaching them, was among the rationales for the first suburbs. Jane Addams among others argued that children grew up best in the country, far from the moral and physical contagion of the city streets.

where with Mom in the minivan — the baby carriage with cupholders and airbags — or retreat into infantilism. Being chauffeured everywhere makes young kids lazy; the Centers for Disease Control has reported that less than 1 percent of today's kids aged 7 to 15 ride bikes to school, a figure that has been shrinking over the past 25 years.

What the cul-de-sac is to the subdivision, the subdivision is to the town. Its isolation behind barriers of zoning law and a rat's maze of streets imposes a physical isolation that is perhaps the single biggest problem for kids.

Single-use zoning separates

kids from work, from nature, from adults other than their parents. Grownups may see kids' social needs in terms of peers — having friends, being popular — but just as important for kids past a certain age is contact with the larger society. In the place of farm chores or helping pop in the shop downstairs, we offer "activities" or jobs, when what kids need and want is opportunities to do useful, interesting work.

One of the few critics to consider the needs of kids is Philip Langdon, who visited Naperville and Oak Park while gathering material for his 1994 book, A Better Place to Live: Reshaping the American Suburb. "For a full connection to one's society and surroundings," he concluded, "there is no substitute for direct experience. Yet this is sharply limited by the layout of the recent suburbs. A modern subdivision is an instrument for making people stupid."

For evidence of the baleful effects this kind of upbringing can have on children, we need look no further than the parents of today's kids. Reporter John Herbers in The New Heartland recalls that the kids of the newly suburbanized World War II generation "grew up like hothouse plants in an isolated environment." They did see enough of the real world to learn that it is filled with racism and class inequality and war. Herbers assays that the youth rebellion of a generation ago was more than anything else a product of "an extraordinary idealism." One might better say an extraordinary naivete.

Differences? Of course. The boomers suffered social dislocations as a result of their

deprivation, which left them prey to a politics of illusion; their kids' dislocations tend to be psychological. Today's cowed and coddled middle-class kids tend to turn their anger inward and vandalize their own bodies through eating disorders, scarring or drug use. And of course there is Littleton, which has been to the suburban idyll what My Lai was to the myth of American righteousness.

While subdivisions have hardly changed physically in 25 years, what made them an OK place for kids a generation ago — the social infrastructure — is largely missing. Feminists in the late 1960s and early 1970s (one of them Peoria's Betty Friedan) complained that subdivision life starved the stay-at-home wife of social contact, left her with no challenge more stimulating than opening a can, and rendered her lonely and incompetent. Twenty-five years later, the subdivision is a better place for moms, if only because so many of them no longer spend all of their time in it. Most women work at least part-time, for example, as part of the middle class's Faustian bargain:

To afford a nice house to raise the kids in, women have had to leave their kids.

Alas, because mom spends more time out of the house, kids spend more time in it. Kids' now-vanished freedom to roam their world with their companions was made possible by the presence of women who acted as referees, monitors and emergency nurses. And diversity, good in other ways, has undone the very thing that made the first postwar subdivisions good places for kids by eroding the consensus of values that owed to social homogeneity, a consensus that enabled young parents to trust neighbors as they might an extended family when it came to the nurture of each others' children.

Protecting children, as distinct from teaching them, or nurturing them, was among the rationales for the first suburbs. Jane Addams among others argued that children grew up best in the country, far from the moral and physical contagion of the city streets; the suburban-style house, with its half-acre of private, fenced-in country, was a happy compromise. The earliest English suburbs went further, offering what one resident recalled "delightful wilderness" in the form of a common of quarry pits and groves, and space at the end of yards laid out for children's games. Land costs rule out such amenities in developments aimed at the middle class, even if liability lawyers are not whispering into the ears of developers.

The advantages enjoyed by today's subdivi-

32 / November 1999 Illinois Issues

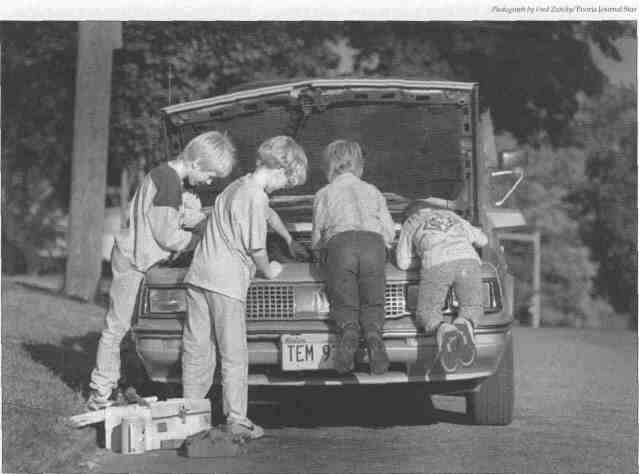

sion kids are (save physical safety) largely private, not public goods. The standard subdivision makes remarkably little physical accommodation to children's needs. Even the feature that works best for kids was not invented for them. The cul-de-sac was intended to cut through traffic, but it also serves as an impromptu play area for younger children. The space is close to houses and visible; kids are relatively safe from cars; and the paved surface is ideal for many games.

If anything, kids are designed out of subdivisions. Drive through the poor districts of any Illinois city and you will see front yards worn to mud, toys scattered, porches that bear the scars of children at play, baskets nailed to light poles used as impromptu basketball hoops. This is simply not allowed in most subdivisions, where children's social and emotional health is indulged only up to the point that it risks property values.

We fear more than ever the unoccupied child's capacity to get up to mischief. If Jane Addams wanted to get kids off the streets of Chicago to protect them, we

want to get them off the streets to protect us. The wildness in the young is, if not best expressed, certainly most conveniently expressed in wild places, which is why the interstices of the city have historically been commandeered by its youth for their necessary rituals and trials. (Formal city parks were founded in large part because other open spaces have been taken over by local ruffians for games that were, to their betters, indistinguishable from fights.) Ralph Waldo Emerson once prescribed a pasture and a wood lot as the best cure for juvenile village mischief. Writing a century later, Lewis Mumford argued in favor of the dispersed city on the grounds that youthful "homicidal impulses could be exorcised" by hunting, swimming or climbing. The only subdivisions that still offer those outlets are those on the very edge of the urban frontier, where the setting as well as the ambiance is rural. The social costs of adolescent high jinks unfortunately are borne by neighboring farmers, often with the indulgence of citified parents who can't tell a bean field from a park.

Lacking a pasture and a wood lot, older kids still tend to appropriate those parts of every neighborhood that grownups don't want or need. The problem is that there are few such places left in the postwar subdivision because of the way they are built. Every lot is owned originally by the developer, whose bottom line depends on exploiting every square yard of land. The result is that the subdivision has no wasted space into which the energies of kids might be safely poured, no places where inexperience, curiosity, a need to find and try limits of appropriate behavior can be tested. We can wonder whether so many slip into a premature adulthood because there are so few places in which they can be kids.

Subdivision design suits the needs of parents rather better. It would be hard to come up with a setting on the neighborhood scale in which controlling children could be more convenient — an unacknowledged factor in their popularity as a venue for family life. Too bad that a good place to raise kids is not always a good place for kids.ž

James Krohe Jr., a contributing editor of Illinois Issues, has written extensively about architecture and urban planning.

Illinois Issues November 1999 / 33