|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

P • O • E • T • R • Y

The Chicago Renaissance in Poetry

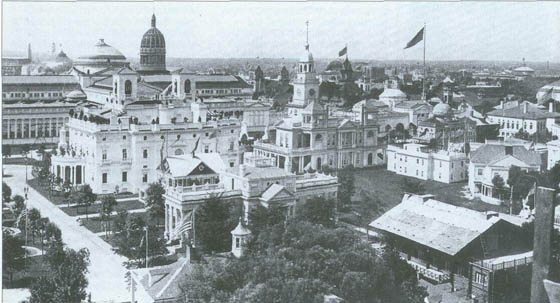

Dan Guillory The Chicago Renaissance was a brilliant and diverse period of literary productivity having as its focal point several crucial events: the creation of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse (1912) and the publication soon thereafter of Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Carl Sandburg's Chicago Poems (1916), two texts that could easily be credited with inventing "modern" poetry in the United States. The Chicago Renaissance may be narrowly defined as covering the period from 1900-1920, when its most characteristic productions appeared; but, broadly conceived, it embraces the years 1890-1925, including earlier writers and journalists such as Eugene Field, George Ade, Henry Blake Fuller, Hamlin Garland, Robert Herrick, and William Vaughn Moody. These early practitioners discovered the city of Chicago as a possible literary subject, and they were the first generation to document its unique scenery, speech rhythms, ethnic dialects, and diverse occupations. Let me stress, however, that the Chicago Renaissance is primarily, though not exclusively, a literary phenomenon. The preconditions that facilitated that great cultural explosion are deeply rooted in the history of the city itself, beginning perhaps with the first great moment of self-consciousness in April 1865 when the city of Chicago, draped with black crepe bunting, received the funeral train of Abraham Lincoln, as that tragic cortege made its way to the state capital of Springfield. At that time, Chicago was barely four decades old, but its justifiable sense of self-importance had been dramatically increased by the Civil War and by the emergence of "the Windy City" as a manufacturing center and transportation hub, especially for the rapidly expanding railroads. Then in October 1871, the Chicago Fire raged through the center of the city, creating momentary panic and devastation but leaving a tabula rasa or "clean slate" upon which the new city could be built. The Chicago Fire of 1871 literally cleared the way for great architects like Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. And Wright's "Prairie Style" of domestic architecture inspired others to seek innovative and bold solutions to aesthetic problems. Before the turn of the century, Chicago became a venue for the University of Chicago (1892), the World's Fair (1893), and the Pullman Strike (1894)—events that helped to define the social and cultural character of the city. By 1908, the year Henry Ford began selling his fabled Model T in Detroit, Chicago had a world-class art museum, The Art Institute, a well-defined commercial center, The Loop (named after its famous elevated train), and a skyline of new skyscrapers—not to mention thousands of recent immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (as well as ex-slaves from the American South) who swelled the earlier population of peoples of German, Irish, and Anglo-Saxon extraction. In those first years of the twentieth century, Chicago was a dramatically exciting place to live and work. The first automobiles (powered by gasoline, steam, and electricity) traced their way through busy city streets where horse-drawn carriages and wagons still abounded. Jackhammers drilled old cement while wrecking balls knocked down walls, and the steel skeletons of skyscrapers stretched higher and higher. The sidewalks were packed with pedestrians, many speaking foreign tongues. Dust, noise, and smoke filled every available space. There were saloons and chop houses and newsstands. The city was on fire again, but this firestorm was a conflagration of the spirit.

A sense of change was in the air, and it was impossible not to be swept up by all the new currents of the Windy City. Chicago quickly became a powerful magnet attracting artists, musicians, actors, and the literary-bohemian set, including such famous novelists as Sherwood Anderson (Winesburg, Ohio) and Theodore Dreiser (Sister Carrie). Into this vortex came three particularly important writers, all known for poetry, although they all wrote essays, biography, and journalistic articles as well.

Carl Sandburg (1878-1967) was a product of the Swedish immigrant community in Galesburg, Illinois, where he had attended Lombard College before roaming the byways of America, finally settling in Milwaukee, where he became active in Socialist politics. These facts are important because, unlike the so-called "genteel" and aristocratic writers who preceded him, Sandburg was attracted to the working class, the people who lived in the tenements and slums that were also a part of Chicago, the newest citizens with dirt under their fingernails. Unlike, say, Henry Blake Fuller who wrote of the upper classes and took a rather negative view of the city, Sandburg was an optimist whose tone remained positive even in the most trying of circumstances. Significantly, Sandburg later composed the most optimistic literary document of the dark days of the Great Depression, the long, oratorical poem The People, Yes (1936). In 1914, the year the First World War began, Carl Sandburg was lifted from obscurity by winning a prize for a group of poems including the famous free-verse masterpiece, "Chicago," which became the centerpiece of his first book, Chicago Poems (1916). Although other American poets, like Walt Whitman, had written about the city, for them the city tended to remain in the background. Worker-citizens were depicted by their occupations (printers, teamsters, carpenters, and so on) rather than by their particular identity. In one bold stroke, Sandburg composed a unique testament to Chicago by, first, personifying it as a boxer-worker, "a tall bold slugger set vivid against the little soft/cities." Second, he invented an appropriate free verse form that suggested the improvisational (jazz-like) quality of the expanding grid of streets, viaducts, and skyscrapers (a potentially endless series) while echoing the rhythm of jackhammers and drill presses and other forms of pounding, metallic technology that defined the city as a kind of human machine:

bareheaded,

There is no trace of gentility in this poem; it shatters forever the old, genteel assumptions about proper form and content by including allusions to prostitutes ("painted women"), murderers (the gunman who goes "free to kill again"), and the urban poor (women and children whose faces are marked by "wanton hunger"). American poetry would never be the same after "Chicago" and its brutally graphic opening line, "Hog Butcher for the World." But these grim realities are transformed into strengths by the rhythmical pounding of the verse, and by the optimism of the "urban slugger" (Sandburg uses seven forms of the word laugh to characterize this persona of the Windy City) who, at the end of the poem, is significantly "proud" to be the meta-worker combining butcher, tool-maker, and railroad worker. So the poet concludes on a profoundly optimistic and democratic note. The poem is American to its very core, the authentic product of an Illinois poet only one generation removed from the "old country" of Sweden. Like so many others, Carl Sandburg had fallen hopelessly in love with the city; but, unlike the others, he had found a verbal construct to encapsulate and celebrate his feelings. I have always thought that "Fog," the other famous poem in the book, may well have been written as a kind of coda or footnote to "Chicago." Its brevity and Imagist style create a memorable antithesis to the urban hustle and bustle of the longer work. Once again Sandburg uses a controlling metaphor (here, the cat) to endow the amorphous fog with shape and feline personality. It comes "on little cat feet," surveys the skyscrapers "on silent haunches/and then moves on." One could very well imagine a thick bank of fog, moving across the waters of Lake Michigan, stealing into the Yacht Harbor, then silently creeping into Grant Park and the concrete corridors of the Loop itself.

3

Less sanguine about life in general but equally focused on the lives of ordinary men and women, Edgar Lee Masters (1868-1950), a Chicago lawyer who had grown up in the downstate communities of Petersburg and Lewistown, met Carl Sandburg in 1915, about the time he began the serial publication of his masterpiece, Spoon River Anthology (1915). Based loosely on the lives of people in his own family and in the hometowns of his boyhood, Spoon River Anthology is ultimately modeled on The Greek Anthology of classical antiquity. Masters employs the highly effective strategy of having people speak frankly from the grave, where no further harm can befall them. Most of the speakers in the imaginary town of Spoon River (named after the real river in Western Illinois) have suffered some indignity, treachery, or injustice during their lifetime. On the whole, these are not happy utterances. Nearly every citizen has gone to the grave with some dark secret, like Elsa Wertman, the "peasant girl from Germany," who was seduced by her master (Thomas Greene) while she was working in the kitchen. After her "secret began to show," Mrs. Greene successfully schemed to pass off the baby (Hamilton Greene) as her own. Hamilton becomes a famous and eloquent politician, and the poem concludes with Elsa's poignant admission that she cried during his speeches, apparently having been moved by his powers of speech, but

That was not it. If bad marriages figured prominently in the pages of Spoon River Anthology, it was surely because of Masters' own unhappy marital experience and that of his parents. Masters was flagrantly unfaithful, justifying his conduct in part with the social theories of Free Love and "liberation," which were widely discussed by the intelligentsia of the period. But he found little happiness or solace in his series of extramarital adventures. Speaking perhaps for Masters and many of her fellow characters, Margaret Fuller Slack, driven to the extremes of endurance by a bad marriage, exclaims that "sex is the curse of life!" But some sunny patches persist, even in the dreary confines of Spoon River. Old Hannah Armstrong speaks fondly of visiting President Lincoln in Washington to secure the discharge of her sick son during the Civil War. Fiddler Jones is still able to savor the poetry of the earth, the loveliness of the landscape in Menard and Fulton counties, where Masters grew up. Fiddler Jones summarizes his life this way:

I ended up with a broken fiddle— And Lucinda Matlock lives to attain the age of ninety-six, dying one of the few peaceful deaths in Spoon River. Her whole life has been an existential affirmation of life, and she concludes thus: "It takes life to love life."

4

Yet the single most unifying element in the lives of all these writers was Poetry: A Magazine of Verse (1912), the brainchild of poet and essayist Harriet Monroe (1860-1936), who was herself a member of the Little Room, a genteel literary society that flourished between 1895 and 1910. Literally passing the hat among her genteel and well-heeled friends, Miss Monroe gathered enough funds to begin publication in 1912 and quickly transform the magazine into a self-sustaining operation. Libertarian in spirit, while maintaining the highest editorial standards, Harriet Monroe published virtually every important American poet of the period, helping to launch the careers of such notable writers as T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, Vachel Lindsay, Edgar Lee Masters, and Carl Sandburg. Two other important literary journals, The Little Review and The Dial, also operated in Chicago, but their operations were quickly moved to New York City. Poetry became the "in house" organ of the Chicago Renaissance, the central hub upon which everything else turned. When the Renaissance had finally spent its energy (by the mid-1920s—the era of Al Capone), Poetry remained in Chicago but became national in character and readership. Although Harriet Monroe died in 1936, Poetry is still being published today. Sandburg's Chicago Poems and Master's Spoon River Anthology have never gone out of print. The best of the Chicago Renaissance has become inseparable from the literary life of America, because like all great literature—in the words of Ezra Pound- it is "news that stays news."

Click Here for Curriculum Materials

|

|

|