The face of vulnerability

Who's most at risk of going hungry?

Losing a job? Beware. It just might be you

by Anne Keegan

Photographs by Nathan Mandell

D on't look for Dianne Banis in the unemployment stats. She isn't there.

"I've disappeared," she says. "I don't exist there anymore. I don't count."

Banis has been out of work for almost two years but not because she hasn't tried to find a job.

"I would say I have heard at least a dozen to 20 times that I am 'over-qualified' for the job," she says. "That means I am too old. They don't say 'old'; they say 'overqualified.'"

Banis is 57. She has worked as a reporter, editor and public relations specialist for the last 30 years and now can't find a job. She lives a life of credit roulette, borrowing off one credit card to pay the other credit card, which paid last month's bills accrued the month before that. When her unemployment checks stopped after six months, she says, she fell off the statistical map. She wasn't counted as unemployed anymore. She can't find her name on any list.

But as invisible as she may be statistically, she is still there -- broke, and wondering what has happened to her and why, in this so-called low-unemployment, booming economy.

A quarter of a century ago, Banis was also out of a job when the newspaper she was working for folded. She went several months before latching onto a new position.

At no time, during that brief era, she says, "did I panic. But my friends were kind of embarrassed about me not working. They didn't know anyone who didn't work, so we didn't talk about it. Only bums didn't work, and I knew I would find a job. And I did. And it wasn't hard."

But she can't find a job now. And she is panicked. Her friends are no longer embarrassed to talk about it with her, and they do so with a bit of panic themselves and a lot of empathy in their voices.

12 January 2000 Illinois Issues

|

"There's not a one who isn't worried it will be him next who will lose their job, or who knows a friend, a neighbor or a relative that this has happened to. People over 50, still young, thank you, lost their jobs or got downsized, and can't get employment because they are 'overqualified.' No, they can't get employment because they are too old."

Banis is one of a growing number of people 50 to 65 years of age -- the official age of retirement and elderly Social Security benefits -- who fall into an employment twilight zone because they were making too much money, have been downsized out of their jobs, were encouraged to leave their positions ("constructively discharged," they call it), were bought out, or had their jobs eliminated, and now suddenly, to their shock, cannot get hired again.

Saying someone is too old to be hired is against the law. But saying someone is "overqualified" is not.

Banis, at her age, is vulnerable. She is in a new category on an old list. But, then, there are many "vulnerables" in our society.

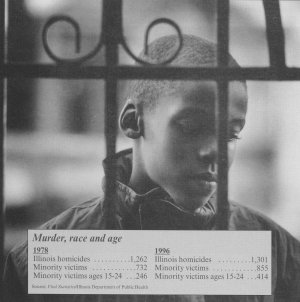

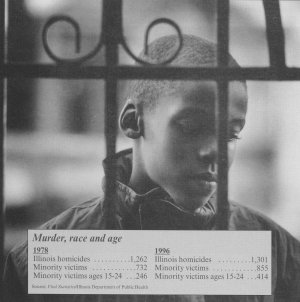

Who are the "vulnerables?'' Ask a social policy researcher, ask the lady next door, ask the neighborhood bartender, ask your uncle who comes over on Sunday afternoons for dinner. Ask all of them who the vulnerable people are in our society today. Was it any different 25 years ago? Will it be different in the new millennium? They all will give you different answers. The list, in some ways, is uncharted territory because, as in the case of the unemployed Banis, statistics do not tell us everything. Numbers may add up, but they don't tell human stories. They don't cry, they don't bruise and they don't die. By the time statistics are collected, history has already happened. Statistics tell us that the economy is booming right now, that there is only a 4.1 percent unemployment rate. But the unemployment rate does not specify how many of the 6,110,463 employed Illinoisans have jobs that are part-time or have no benefits. Or whether two jobs are being held by one person who's been downsized from a once-better paying job so that working two jobs is how he or she makes the mortgage. Statistics tell us we are now spending more than we make, and that some company CEOs make more than 400 times what their employees make, but they don't tell us why. They also tell us that we have low inflation rates and are the strongest economy in the world. But statistics are not a perfect mirror of reality, and many in this turn-of-the-century, change-of-millennium economy just do not see themselves reflected in the count. They feel lost. And they feel vulnerable. Leon Dread, a reformed ex-convict, thinks the most vulnerable is the young black male. In 1974, just after Dread came home from Vietnam, got out of the Army and returned "wild as all outdoors" to the streets, he landed in prison for robbery. Back then, he recalls, there were nine prisons in Illinois. Today, there are 26. Back then, there were 6,000 people in prison. Today, there are 45,000. Of that locked-up population, 65 percent are black, though blacks make up only 15 percent of Illinois' population. "We aren't giving much vision to boys -- to the young men," says Dread, who now works for a drug rehabilitation program for those

|

13 January 2000 Illinois Issues

|

convicted of crimes. "Look at the number of prisons today. Look at who is in them. It isn't just young black men. There's whites too. But look at the number of young black men. How did they get raised? Who is teaching them to do right? There's problems in this society when these young men keep getting into trouble and can't function right in society. We've got to do something."

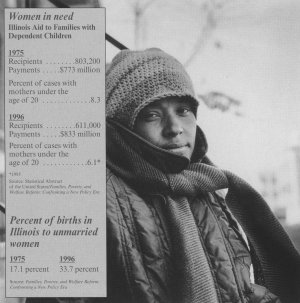

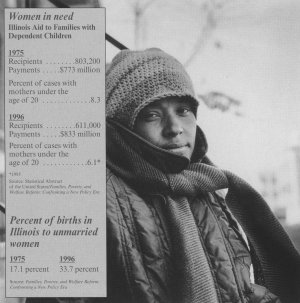

The story he tells is a grim one. Unfortunately, there are others like it. "The most vulnerable are the single female heads of households," says Paul Green, a professor of policy studies at Roosevelt University in Chicago. "Dan Quayle was on the mark a couple of years ago being critical about a single woman having a baby. But not with Murphy Brown. Or anyone like her -- not a Univer-sity of Chicago graduate or a woman with a law degree. It is the single woman working at a supermarket, shopping at K-Mart, struggling to pay the bills, supporting her kids alone. These women are defenseless. They are the ones we should be worrying about, they and their kids."

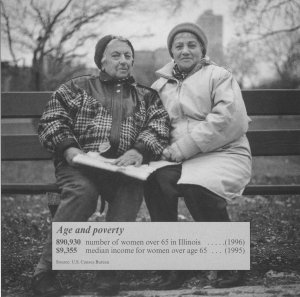

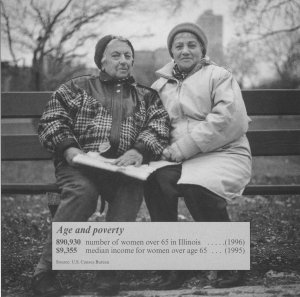

Ah, but those women have youth at least. "The vulnerable? Oh, I would say it is the old, the older women, alone and frail," says Roberta Mezinskas, a painter from the McKinley Park neighborhood of Chicago. "Living on Social Security. These are the ones who shop alone, walk alone and live alone and don't have enough money to pay for food and medicine both. They survive on soup and crackers. At our parish, a nice working-class neighborhood, the seniors club hands out box lunches every day, and every day [the club] is filled. These seniors, you know, aren't homeless. Their homes are the only pride and security they have left. But that's all they have left. I know some of these women who own two flats and the upstairs apartment sits empty for years. They could use the income but they are too afraid to rent it for fear of who they'd get in there -- and then couldn't get them out. They are very vulnerable and don't have much money to live on." "Who are the vulnerable? I guess that's me," says Dorothy Johnson, 78, who lives in public housing in west suburban Cicero and who, once upon a time a quarter century ago, quit her job and took on the sole responsibility of raising a set of triplets who'd been abandoned by their young teenage mother. Johnson's natural children were already raised, so she adopted the three children and gave them a home. She lives now on $636 a month, her Social Security. She pays $101 a month for public housing and "without the public housing," she says, "I wouldn't make it.'' Sharing her apartment is one of her triplets, a 30-year-old daughter, unmarried with two kids. "I may be vulnerable but there's a lot of mileage on this old lady," says Johnson. "But I do think the new vulnerables are young women like my daughter who don't have a husband, or make much money, or know who they are and what they are doing, and are raising kids. Where are their own kids going to go when they grow up?" Of course, deciding who is vulnerable is a matter of perspective. "Let me tell you a little story," says Illinois' former U.S. Sen. Paul Simon, now a professor at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. "I was

|

14 January 2000 Illinois Issues

|

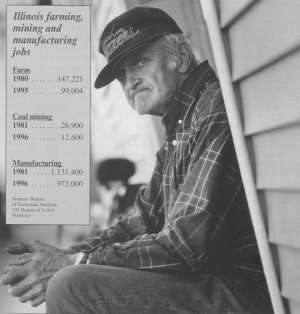

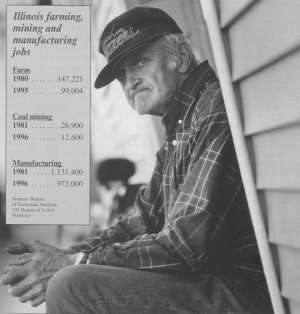

asked to give a speech at a library dedication a while ago and to compare Lincoln's time with our time now. So I pointed out that in Lincoln's time the most powerful country in the world was England. It had the greatest economic power and the greatest military might. But it had some of the worst living conditions for the poor, and Americans were shocked by that. Now, today, we are the most powerful country in the world, with the greatest military might and the greatest economic power, and we have some of the poorest conditions of poverty with mothers and children. And 100 years from now we will look back and wonder how this could be tolerated." Times change. For instance, working the land has always carried its share of hardships. But in the year 2000, there's a whole new set of man-made hurdles for farmers. Larry Quandt of the Illinois Farmers Union is worried about the 5 percent of the state's family farmers who might go under this year. That means losing their land because of low crop prices. There are 70,000 farmers in this state, and many are living on the margin -- due, Quandt says, not to lack of hard work or poor soil, but to the collapse of the Asian and Russian markets, bad farm policy and overseas trade agreements. Specifically, his union wants two simple policy changes to help many farmers make it through these times of depressed crop prices: an extension of federal loans from nine months to 15 months and the creation of a farmer-owned "reserve program" that would let farmers sell grain when they choose, rather than at harvest time. They also want the government

to help reduce the price of grain storage. "There's been a lot of federal money spent," says Quandt, "but not spent well."

"We have a lot of farmers, a whole lot of them, who are vulnerable," he says. "And what is happening to them is scaring the daylights out of me." Quandt is pushing for a state initiative to help retrain those who are being forced off their farms.

"They did it for factory workers in the state, miners and other employees who were downsized or lost their jobs, but never for the family farmer. I don't think there is such a thing anywhere in the country, so maybe we in Illinois could be the first."

U.S. Rep Lane Evans, from the Rock Island-Moline area's 17th District, thinks the American veteran is getting the short end of the stick. A veteran himself, he says that in the last 25 years, there has been less money allocated for veterans and less respect for them coming out of Washington. He sees veterans as vulnerable. But he also sees a broader picture,

"I've heard this said, that if a John Deere worker gets laid off after 23 years and has to go get a job for a lot less, and his wife, who has no skills and never worked before, goes out and gets a job too to support the family, there are those who would say statistically, 'Oh, there are two new jobs being created.' But what you really have is a family living on 50 percent of what they used to make, and what you are seeing is the beginning of the decline of the American middle class. Maybe that's who's vulnerable. The American middle class."

|

15 January 2000 Illinois Issues

|

Once, most Americans could expect job security and a comfortable retirement. Not anymore. "My thought is that in the last 25 years, we have seen people of our generation spend their lives at one company and be rewarded with decent pay, the promise of a decent pension and respect," says Margaret Blackshere, secretary-treasurer of the Illinois AFL-CIO. "That isn't going to happen anymore. No one is going to have just one job in their lifetime anymore. It's not like what it was in 1974. They will move from job to job. This whole issue of part-time workers, no benefits -- and these are the younger workers. Who is going take care of them? I think they are the very vulnerable. They will not be as well off as we are; so will we, in our old age, be taking care of them? How many people do you know who have 30-year-olds who've moved back to live at home?"

There are no statistics to answer Blackshere's question. Not yet. David Rubenstein, a sociology professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, foresees a new group of "vulnerables,'' a large group that few gave much thought to as we entered the last quarter of this century. But it is being thought about seriously now.

"I think the most vulnerable in our society will be the ones who are not going to make the transition into the information age -- the ones unable to absorb, create or transmit information and knowledge on the computer," he says. "There is a historical perspective here. Anytime you have a new technology development, you get growing inequality in society. At the beginning of the 19th century, those who had steam power and those who adapted to that new technology thrived. Others fell behind. In the beginning of this century, we got electrical power. Same thing. Some thrived, others fell behind. Inequality bursts open when new technologies enter into society. We are seeing the beginning of that now, and it will become more so."

The new "vulnerables'' in our midst, based on access and knowledge of the computer, could create social classes as disparate as were those 200 years ago between people who could read and write and those who could not. Their economic status was based on that. Those that top the list of the "vulnerables" today: • The young black male. On any given day in the state of Illinois, nearly one in three in the age group of 20 to 29 is under some form of criminal justice supervision, be it in prison or jail, probation or parole. He also faces an annual unemployment rate of 8.9 percent, more than twice the rate of the average Illinois citizen. • The single mother raising children alone. There are 671,000 of them in Illinois, but despite the feeble efforts of the Illinois Department of Public Aid to enforce payment, only 12 percent receive child support checks from the fathers. Their average income is $12,000 to $15,000 a year. • The elderly who eke out a meager existence on soup and crackers. There are close to 1.5 million people in Illinois now over the age of 65, and this group will grow substantially as the baby boomers age. Currently, they make up 12.5 per cent of the population. In 1996, 8.6 percent were living below the poverty line. Older women had a higher rate of poverty at 13.1 percent than older men at 7 percent. The median income for an older woman was

|

16 January 2000 Illinois Issues

|

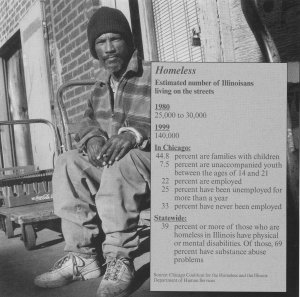

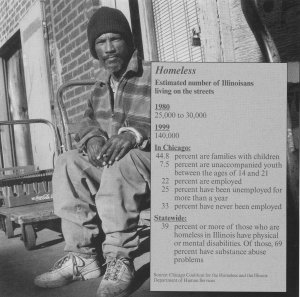

approximately $10,000 a year. • In Illinois, homeless advocates estimate 140,000 people are living on the streets because of such problems as mental illness, substance abuse, unemployment and underemployment. Affordable housing in the Chicago metropolitan area is a scarce commodity.

Then there are the one million Illinois veterans who are seeing the budget for them slowly deflate, the increasing number of workers with no health benefits and the farmers who must work a part-time job just to keep the farm, and raise the crops and the kids.

But is the state of social vulnerability purely financial? Are the only ones not vulnerable, as Paul Fanning, an old-fashioned liberal and former radio talk show host, says, "the ones who have accrued screw you money. Them and those CEOs who never lived in fear of FDR or the Depression and so in the last 25 years had no reason to restrain their greed?" Chicago attorney Tom Geoghegan, who has represented the workers in court, has a vision of the vulnerable condition that goes beyond the material. "We are all frail, mortal and going to die. But today, in this economic climate, I think even the so-called winners are more vulnerable than they know. They are leading lives more vulner-able than they realize. The hours they spend at work. Friends, family, the reflective dimension of life, they aren't getting any of that. I think there are people further down the income scale of the so-called winners who are better off. The winners are being cheated out of a real life and the moment they lose that job, they find there is no one around to back them up. "This is not a financial liability, but when a person is robbed of a real identity, what have you got? This is a society now that has a high amount of poverty on all income levels, emotional, cultural, financial. But I want to make it perfectly clear, I feel much more sorry for the very, very poor." So who is it that we must address our attention to as we leave an old and tired century and face a new one? What group should we take in and cradle in our hands? Is it the young black male, the single unmarried mother? Is it that independent sunburned farmer about to lose the family's land? Is it the veteran who's lost an eye? The middle-aged worker over 50 pushed out of a job and not getting another? Is it the homeless guy sleeping in cardboard under the railroad trestle? The elderly lady who lives on soup and crackers? The kid who never mastered a computer? Who are the vulnerable anyway? Perhaps Tom Geoghegan says it best.

"I'm afraid it's probably all of us."

|

Anne Keegan is a Chicago writer who worked as a reporter for the Chicago Tribune for more than 25 years. Funding for the magazine's focus on the lives of the vulnerables in this issue is

provided by the Woods Fund of Chicago.

17 January 2000 Illinois Issues

This page is created by

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator

Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the

Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library

|