|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

A public fed up with banal buildings, uglified vistas and traffic jams has given political potency to calls for reform of suburban development. But while most people agree suburbs ought to be different, no one quite agrees on how. Riverside, just west of Chicago, was an influential model for the 19th century railroad suburb, and Schaumburg is an archetypal 20th century auto suburb. What ought 21st century suburbia look like? What is its ideal density, the relation of its public and private parts, its provision for nature?

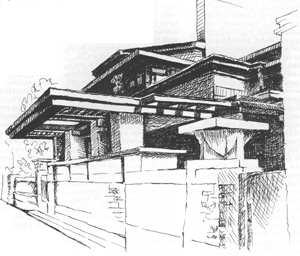

One answer to that question — “Broadacre City”— was announced 70 years ago. Broadacre City was Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision for the ideal multicentered, lowdensity, autooriented suburbia. Measured by the number of years he spent at it, Broadacre City was the chief work of Wright’s mature life. The architect introduced his scheme for a decongested city in 1932 in the book, The Disappearing City, and revised and expanded the concept until his death in 1959.

Broadacre City had virtually no discernible impact on the way cities were built; indeed, it is possible to earn degrees in architecture or planning and never hear of it. Yet the urbanizing fringes of Illinois’ cities look remarkably like what Wright imagined 70 years ago, at least in major aspects. If Wright did not inspire postwar development patterns, he anticipated them brilliantly. Most visionaries have a plan. Wright had a model — a 12foot by 12foot wooden model of Broadacre City that illustrated the concept as it might be applied to a representative foursquaremile plot of land. It shows a nowfamiliar network of superhighways linked to a regular grid of arterial roads. The major intersections, as points of access and concentration, were the natural sites of large “markets”— embryonic Woodfield Malls — as well as churches and other institutions of mass civic and cultural life. In terms of land use, Broadacre City honored the precepts of Progressive era city planning that still shape

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 27

In terms of population density, Broadacre City scarcely deserved the name. Because families would be accommodated on lots of one to five acres, population density would be a very low five people per acre. (Officially, "urban" areas have at least 15 people per acre.) Apart from its density, the scheme was not very radical, certainly not when compared to the work of such other city inventors of the era as Swiss architect Le Corbusier. Broadacre City was not so much imagined as reported. Wright did not look into the far future for inspiration, indeed not into the future at all — only as far as 1920s Los Angeles and the Arizona desert around Phoenix, where the nation's first automobile suburbs were already beginning to sprawl.

Broadacre City today is usually dismissed as a rationale for sprawl. In Broadacre City, writes historian Peter Hall, Wright wove together virtually every strand in American antiurbanist thinking. In fact, Wright had proposed not a new kind of suburb but a new kind of city. Wright deplored the suburban expansion already underway, by which the 19th century industrial city he hated — of which Chicago was the American archetype — appropriated the countryside. Wright was inspired to invective by Chicago the way Vachel Lindsay was inspired to verse by the flowerfed buffalo. His Broadacre City was not a city set in the countryside, a la Ebenezer Howard's turnofthecentury Garden City concept. Rather, it was the countryside converted into a city that would be an improvement on both. No mere dormitory, its spreadout parts would compose an urban whole, with each family enjoying access to small farms, orchards and recreation areas, but with light industry and other urban facilities all within 10 to 20 miles of their house.

Landuse patterns were not all that would have changed under Wright's plan. The physical layout of Broadacre City embodied a program for economic reform that was the keystone of a model democracy he called Usonia. His Usonia would be a bastion of antiMarxist socialism whose outline was traced from the writings of such 19th century utopians as Thorstein Veblen, Henry George, John Ruskin, Pyotr Alekseyevich Kropotkin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Edward Bellamy and such nowforgotten cranks as C.H. Douglas and Silvio Gesell. Families would be freed from the yoke of the banker and the landlord. The means of production — anachronistically assumed by Wright to reside in the land — would not be held by the people in common but would be dispersed to them individually. Land would be taken into public ownership, then granted to families for as long as they used it productively.

Usonia was based not on cooperation but fierce individualism. Here he was more in touch with the average American than was the patrician Daniel Burnham or the communalist Jens Jensen. Broadacre City offered a means by which ordinary Americans might live in what the great urbanist Lewis Mumford called "romantic isolation and reunion with the soil" while enjoying urban economic opportunities and recreations. Broadacre City was Wright's White City, certainly, but one that owed as much to Dan'l Boone as to Dan'l Burnham.

Houses were to be designed as well as built by their owners in any style they wished. The neighborhoods would be individualism expressed in brick and wood, with no two houses alike, so long as they, like all structures in Usonia, were — in Wright's words — "integral, natural to their sites, materials, construction method and purpose." That crucial judgment about what constituted integral and natural was to be made by the central civil authority, in the person of what amounted to a county architecture czar. In his 1983 book, Man About Town: Frank Lloyd Wright in New York City, Herbert Muschamp pointed out that Wright's principled emphasis on individual sovereignty precluded the very civic order that his plan promised to provide.

Architecture critic Witold Rybczynski summed up the general view by describing Broadacre City as an "embarrassing foible of an aging master." Mumford praised it at first: "On the whole, Wright's philosophy of life and his mode of planning have never shown to better advantage," he wrote in 1935 — but 30 years later Mumford condemned the plan's "sprawling, open, individualistic structure" as being "almost antisocial in its dispersal and its random pattern." Muschamp, now the architecture critic of The New York Times, concluded that the plan was "too real to be Utopian and too dreamlike to be of practical importance."

Certainly Wright got a lot wrong. Suburbia will never match Broadacre City's low densities. The trend is toward more density rather than less, especially at the transport nodes where offices, assembly plants and other "higherorder central place functions" are accreting. As Rybczynski put it in City Life, "We need both dispersal and concentration in cities — places to get away from each other, and places to gather — and it's time to stop assuming that one necessarily precludes the other." The likely result he describes as "Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre City meets Jane Jacobs' Greenwich Village," the first crude manifestations of which have already been visible for years in such places as Oak Brook, Schaumburg and other citifying centers.

Wright also erred in assuming that free land was essential to a people's ability to support themselves humanely. He did not anticipate the degree to which prosperity would make it possible for millions to buy their own land. The typical suburban homestead turned out not to be the site of wealth production but the source of it. Today, the profits from house sales pay for college for the kids or a retirement home for the folks. Preserving its value by mastering the skills needed to maintain and improve it and its grounds is as close as the typical American family ever gets to the kind of husbandry Wright envisioned.

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 28

The edge city, in short, is an alternative to the central city, not just an appendage of it. The key is the car. Mumford was one of the first to complain that Broadacre City’s configuration would reduce the number of nearby neighbors and thus the opportunities each resident had for social contact. But Mumford was a man of the city, while most Americans have always been reluctant urbanites. (Sprawl is not new; American towns have always sprawled, going back to colonial days.) Mumford’s complaint that Wright’s layout “demands motor transportation for even the most casual or ephemeral meetings” has since been echoed many times, but for most suburbanites this dependence is a practical problem, not a conceptual flaw. Like most Americans, Wright saw the car as a liberating technology. The car would simultaneously make huge swaths of land accessible for development and make it possible to live on it without foregoing social connection. More than most, Wright realized that in an environment so physically attenuated, communities of place would be replaced by communities of interest, bound by telecommunications and transportation.

Visionaries spend more time consulting mirrors than crystal balls when they concoct their Utopias. When park designer Frederick Law Olmsted laid out Riverside in 1868, he imagined the ideal residential suburb as a park. Europhile Daniel Burnham in 1909 imagined the ideal Chicago as Paris. Jens Jensen sought to recreate in his urban plans for Chicago the opportunities for communion recalled from his native Denmark. Wright’s Utopia looked a lot like the rural Wisconsin he grew up in: a highly ordered landscape occupied by craftsmen and yeoman farmers and subordinated to the need to make a living.

That Wright anticipated so much of the past 70 years in suburban development will not recommend Broadacre City to everyone as a model for the next 70. The concept accepts, indeed embraces, the personal automobile and lowdensity development, both of which would be limited were most antigrowth programs ever put into effect. Wright perceived, as many sprawl critics do not, that suburbs did not make the car necessary; rather, the car made suburbs possible.

Peter Hall notes that in postwar suburban sprawl, Americans got the shell of Broadacre City without the substance. A fair enough judgment, if we assume that the substance of Broadacre City is Wright’s program of social reform. In fact, the substance of Broadacre City is aesthetic. What its author envisioned, writes Muschamp, was a “government not of laws but of aesthetics, of architecture, and of Wright.” Thus Broadacre City was not a conventional city plan, rather a work of architecture applied to a particular city form. Wright did not seek to protect nature, for example; he appropriated it. Wright once said the countryside would not be destroyed by having his new city built all over it because “quality of building comes into the picture.” As one rival noted, he was the first architect in history to attempt to design a whole continent.

Broadacre City can be seen as less a plan to rescue the city than a plan to rescue architecture — or perhaps to rescue one architect in particular. Skeptics pointed out, not unfairly, that the Broadacre City model was a perfect sales presentation prop for what amounted to continental real estate speculation with Wright as chief architect. It would have been his way of restoring his profession to a central role in articulating civic order usurped by planners and developers. As Muschamp has put it, Wright was not against cities, exactly, only against cities he didn’t design.

That Wright anticipated so much of the past 70 years in suburban development will not recommend Broadacre City to everyone as a model for the next 70. The concept accepts, indeed embraces, the personal automobile and lowdensity development.

In this, as in so many other ways, the world is still catching up to Wright. While his architect czar may never materialize in that form, the grounds on which local agencies assert a public interest in building decisions grows longer each year. For example, citizens, acting as both customers and voters, are more demanding that aesthetics at both the landscape scale and the house scale are matters of public interest as well as private taste. In fact, many of the controversies that excite locals to demand public action — preservation of open space, for example, or municipal bans on “cookie cutter” house designs — are aesthetic at root. Aesthetics might yet become a political program in its own right, rather than merely an approvable aspect of individual building projects. Wright’s county architect — elected, and thus entitled politically to act on the public behalf — might find a role after all. .

James Krohe Jr. is a contributing editor of Illinois Issues.

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 29

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |