|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

If you've watched an hour of television in the past four or five years, you've seen those commercials for sport utility vehicles, SUVs for short. Typically, those ads depict a stuffy suburbanite in a suit and tie, who is fed up with crowded freeways and the 9-to-5 and yearning to escape his drab existence in a shiny new Ford Explorer or Jeep Grand Cherokee. Suddenly, he's alive and free, climbing a mountain with a golden retriever in the passenger seat.

Judging by the number of SUVs on the road these days, those commercial fantasies are effective. But the success of the marketing strategy reflects a trend: Americans are increasingly interested in retreating into the wilderness, if only for the weekend.

Trouble is, everyone has a different idea about what to do once they get there. Across the country, mountain bikers, equestrians, all-terrain vehicle riders, hunters, hikers and birders are increasingly crossing paths, not only with each other, but with those who work to preserve and manage the nation's publicly owned parks, forests and wildlife habitats. "There are user conflicts in just about every piece of public land you can think of," says Illinois Department of Natural Resources spokesman Tim Schweizer.

Members of all these groups love nature. But the sheer number of visitors to natural areas can cause problems for the land and its wildlife. And these conflicts are forcing everyone to re-examine the rationale for preserving public open spaces.

It's no secret people are flocking in record numbers to public lands, including national, state and local parks, wilderness areas and wildlife preserves. Recreational visits to the Grand Canyon, one of the most popular national parks, grew more than 9 percent, from 3.8 million in 1988 to 4.2 million in1998, according to the National Park Service. Nearly 287 million recreational visits were made to national parks, forests and wilder-ness areas in 1998.

This growing crush of nature lovers has threatened the nation's natural areas. Gerry Gaumer, a spokesman for the park service, says visitors can create noise that can disrupt wildlife feeding and migration patterns. And auto exhaust can reduce air and water quality.

Officials at Illinois state parks are also seeing more visitors. In 1998, 40.2 million people flocked to the state's 262 parks, forests and fish and wildlife areas. That's up from 39.3 million in 1989. To satisfy the increasing demand for more open space, Gov. George Ryan launched a four-year, $160 million Open Land Trust to help communities acquire and protect natural areas. Late last year, the state purchased the first tract under that program — 1,662 acres in Kankakee County. And last February, Ryan announced $17.8 million in grants to create and improve 93 local parks across the state. "These grants," he said in a printed statement, "will provide important recreational opportunities and open space for the enjoyment of Illinoisans."

Yet creating recreational opportunities and open spaces could present a challenge.

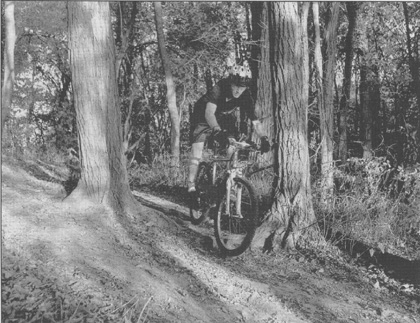

Springfield's Lick Creek Wildlife Preserve provides a recent example. The 340-acre tract lies along the western edge of Lake Springfield, and a 1991 city ordinance designating the preserve permitted hiking and fishing. But it has become favored terrain for mountain bikers. And last year, when a local mountain bike club petitioned the city to allow bicycles into the preserve, a conflict erupted.

The Springfield Area Mountain Bike Association's vice president, Scott Larkin, says mountain bikers have been riding in the preserve at least since the late 1980s without knowing whether they were permitted or not. Actually, the ordinance neither permitted nor prohibited that form of recreation. Concerned that sooner or later they would be prohib-

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 334

But the request raised concerns among environmentalists, including H. David Bohlen, an assistant curator of zoology/ornithology at the Illinois State Museum. Bohlen says the ordinance creating the preserve was explicit. “It is to save plants and animals.”

Two species found in the preserve are on the state’s threatened list. The Brown Creeper, a small bird, and Kirtland’s Snake, according to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, would be adversely affected by bicycling “through encroachment into habitat and degradation of the supporting ecosystem.”

For their part, mountain bikers argue they are no more destructive to the preserve than hikers. “I’m a 190-pound guy on a 20-pound bike,” Larkin says. “How is that different from a 210-pound guy on foot?”

The natural resources department disputes that argument. Schweizer says, “The vehicle itself does more damage to habitat than foot traffic.” The concentrated weight distribution on bicycles creates ruts in trails, he maintains. And bicyclists are more likely to inadvertently kill snakes. Bohlen adds that bicyclists are harmful to birds that require a peaceful habitat to nest and raise their young. “Bikes move too fast. They disrupt the wildlife.” The Springfield City Council split the difference. Last January, it narrowly approved a compromise, allowing mountain biking in all but the most environmentally sensitive parts of the preserve. Violators will be subject to a $50 fine.

But what’s really at issue, in Springfield’s Lick Creek and in other public areas, is differing views of nature and how it should be used.

The bike club’s president, Shawn McKinney, calls the Springfield decision an opportunity for bicyclists to “show we’re responsible and good trail users.” Already, his group has held a cleanup day at Lick Creek, and its members say they want to work with the city to maintain the trails.

Meanwhile, Tom Skelly, who works for the city agency that oversees the preserve, says the compromise was the easy part. Management is just beginning. “If this doesn’t work, we can revisit opening the trails [to bicycles],” he says.

But Bohlen isn’t optimistic. “For central Illinois, which is mostly urban and agricultural, it doesn’t leave much for the wildlife. I think the city council and the mayor set a real bad precedent.”

The Springfield controversy, though, constitutes a minor skirmish compared to the long-running debate over the use of public land in southern Illinois, where equestrians are in a legal dispute with the U.S. Forest Service over access to the Shawnee National Forest.

Bill Blackorby, an equestrian and vice president of the Shawnee Trails Conservancy, which filed the suit, argues the service shut down roads, which in effect will keep visitors out of the forest. In addition to equestrians, his group represents hikers, bicyclists and others who contend the forest is being mismanaged. Rebecca Banker, a spokeswoman for the forest service, responds that “some areas [in the Shawnee] can’t support lots of intensive use over a concentrated period of time.”

Blackorby acknowledges that horses can cause problems. His organization wants to help manage trails and build hitching posts, which he says would minimize equestrian damage. Public lands are for public use, he argues, and people can explore nature in various ways without destroying it. “I consider myself an environmentalist. I love nature. I love the forest, and I sure don’t want to ruin it.”

But to conservationist Bohlen, some recreational activities simply aren’t compatible with the purpose of land preservation. That intention, Bohlen says, is “so that plants and other animals besides humans can live and procreate and maintain their populations.”

In point of fact, nature lovers have differing interests, some of which are in conflict. And in some cases, the greatest threat to nature may come from those who love it the most.

As growing numbers of people make the pilgrimage to Illinois’ natural places, controversies like those over Lick Creek and the Shawnee will continue to crop up. Even as Gov. Ryan tries to satisfy the demand for open space through his land acquisition program, questions about the best stewardship of that land could become more urgent.

Meanwhile, on the trip from suburb to nature, the Ford Explorer, Eddie Bauer V-8 edition with all-leather interior, guzzles gas at the rate of 14 miles per gallon.

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 35

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |