|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

Dream. There is no noun more ephemeral, no verb less vigorous. The very quality of the word suggests an inability to come to grips with reality. In America, land of the hard-nosed, the practical, the man and woman of action, there is little time or patience for the dreamer. Still, dreams do have a way of leaving footprints, for better or worse. Nowhere is this more so than in our own Great Lakes.

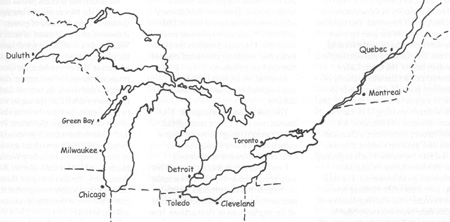

True, the lakes are not often celebrated for their dreamy qualities. They are a vast commercial highway, a bastion of wilderness, a reservoir of more or less fresh water. The Great Lakes are an unimaginative fact, not a dream. They are prosaic. Small wonder our history texts have little to say about the region.

Only when we take the time to dig beneath this workaday image do we find the footprints dreamers have left. Folks have envisioned all kinds of projects to make the lakes speak the languages they wished to hear. Dreams of avarice, of hubris. Dreams of fantasy. The foot-prints are everywhere. Examining them, we learn something of ourselves.

At the eastern end of Lake Superior, not far from Sault Ste. Marie, lies Whitefish Bay, where a barren and inhospitable plain is said to be inhabited by ghosts. Iroquois Point is the stark reminder of a geopolitical struggle that took shape almost three and a half centuries ago. In 1658, two young French traders with more courage than wisdom set out to establish fur connections with Ojibway Indians living on the shores of that lake. Pierre Esprit Radisson and Sieur de Groseilliers were fabulously successful at establishing a new route to the riches of a continent. For those controlling the old way, this spelled trouble.

The Iroquois, headquartered south of Lake Ontario, had been masters of the trade. After extirpating all the furbearing critters in their homeland, the Five Nations lashed outward for control of their northern and western neighbors. A campaign of terror brought them a virtual trade monopoly within the western lakes region. Now the French upstarts had demonstrated a way to outmaneuver the Iroquois. The monopoly was dead.

Dreaming of wealth and power beyond their means, the Five Nations had overreached themselves. Only Iroquois Point remains, a ghostly reminder of dreams unfulfilled.

There are other footprints, too. Near the head of Lake Michigan lies Beaver Island, where one of the strangest stories of the young and restless American Republic played itself out. On this pretty, pine-forested little island, Jesse James Strang tried to make good his dream of becoming a king. By all accounts, Strang was a hypnotic man, clearheaded and rational, yet oddly persuasive. In 1847, when enraged citizens of the central Illinois town of Carthage lynched Joseph Smith, not all of the Mormon flock followed Brigham Young westward. Strang also claimed Smith's mantle, and led a small but determined group first to his lands in Wisconsin, then on to Beaver Island. Here he staged an experiment in alternative government and society, one of many dotting the American landscape during the period.

Strang tried to do good. Assuming various legal hats, he discouraged sale of alcohol to Indians, worked for education reform and promoted commerce. Beaver Island became a regular point of call for steamboats on the lakes, a place to refuel and take on supplies. For nine years, the Mormons prospered. They elected Jesse James Strang their king, providing him with a crown and a coronation ceremony.

But even freely elected kings of quasi-independent islands can go too far. The last straw came when Strang required all women on the island to wear bloomers. A disillusioned follower shot him. As the king died, looters from nearby islands and the Michigan mainland forced the Mormons out. They lost everything.

Strang's is a twisted tale, full of moral ambiguities. A religious zealot with delusions of power beyond his grasp, he sought to destroy much of what is fundamentally American: the separation of church and state, the concept that all are created equal. Yet he was more law-abiding than his neighbors, and sought to save the Indians from the "normal" settlers. He has left an uneasy footprint on Beaver Island, where a few buildings remain.

There were lots of other dreams that came to naught in Lake Michigan. Real American dreams, the essence of our mythologies. Not long before Strang and his followers took control of Beaver Island, a steamship called The Phoenix put in briefly, sheltering from a November storm. The wooden ship, 155 feet

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 38

Steamboats were still relatively new to the lakes. The benefits they brought — superior speed, larger capacities, less dependence on the weather — were balanced by the dangers they posed. In the Midwest, one steamboat of every three plying the lakes and rivers came to a violent end. So many steamboats blew up in the 1840s, Congress launched a national investigation.

The Phoenix was one more such disaster. On November 21, 1847, for reasons no one could ever explain, the ship caught fire, six miles off Sheboygan. Forty-four passengers, the ship’s captain and two additional crew made it to shore. The remainder, including most of the immigrants, burned to death or drowned. Nothing arose from the ashes of this Phoenix.

This was, believe it or not, a story all too common. Men and women, fresh from Europe, alive with visions of a hopeful future, too often already stripped of most of their savings, were stuffed like cattle onto the ships heading westward on America’s longest immigrant highway, the Great Lakes. Storms, fires, collisions and groundings brought the dreaming to a premature and often horrible conclusion. Footprints are scattered on the bottom of Erie, Michigan, Huron.

But all of this is history, and pretty ancient history at that. Iroquois Point, King Strang, The Phoenix , these happened when the Midwest was young, when frontiers were wide and opportunities limitless. We are wiser now. The Industrial Revolution has come, the frontier has gone, the nation has matured in wealth and wisdom. We have made progress. So we want to believe.

More recent footprints scar the shores of the Great Lakes, the traces of wiser enterprises, wiser dreams gone wrong. These are not the products of overweening greed, or projects ill-planned. They are the story of staid American life, and evidence of how fleeting our fondest accomplishments can be. Every generation is consumed with good intentions, and we are just smart enough to accomplish a good deal. We simply do not know what footprints we’ll leave for those who come after us.

At the turn of the last century, Jane Addams envisioned a cleaner, healthier Chicago, freed from the newly discovered germs that bred disease. The result was the ship canal that channels sewage and pollutants southward to the Mississippi. The Chicago atmosphere is healthier, perhaps, but the Mississippi drainage is severely polluted, and the poor folk of Louisiana — down at the receiving end of such gifts from the Midwest — experience skyrocketing cancer rates. Intentions were good, but consequences more profound than anyone could anticipate.

Not long afterward, engineers and inventors seeking an inert compound for myriad uses in electronics and gasoline engines latched onto an araclor, a petroleum byproduct first derived from coal tars in 1881. These PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, were cheap, easy to produce and highly resistant to the heat and pressure generated in manufacturing processes. Before long, PCBs could be found wherever industry flourished. And they can still be found, long after many of those industries have died. PCBs lace the water of inland lakes on Isle Royale, the largest island in Lake Superior. They are ubiquitous in Lake Michigan. We know now that the compound is carcinogenic, a pollutant so volatile that Lake Michigan’s trout, who have no choice but to pass the stuff through their gills, cannot reproduce naturally. PCBs, like so many other chemicals, are a little bit of progress gone horribly wrong.

We really do try. Back in the 1970s, responding to the public pressure of Earth Day and the newly created federal Environmental Protection Agency, lakeside factories and power plants constructed higher smokestacks intended to push industrial pollutants into the upper atmosphere. The result: less air pollution

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 39

Do we learn anything? The buzz at present concerns MTBE, short for methyl tertiary butyl ether, a chemical automotive gasoline additive that was blended into the nation’s fuels beginning in the 1970s to reduce air pollution. Again, such good intentions. The stuff did its job, apparently, enabling several states to come within hailing distance of tougher federal emissions standards. The problem is, MTBE has become still another chemical that attacks the water supply. Whenever there is the slightest gasoline spillage, from a leaky tank or a faulty fuel line, the chemical percolates into the groundwater with frightening speed. From there it moves outward into lakes and rivers. In a decade’s time, it has entered the Great Lakes and several other bodies of water throughout the United States, and continues to do so. Few tests have been performed on this chemical; no one knows to what extent our fresh water supply now poses a health hazard. President Bill Clinton’s administration moved to ban MTBE and urged Congress to promote renewable fuels. This state produces the alternative fuel additive, corn-based ethanol that risks air pollution.

As usual, we try to do good, in a short-sighted and ultimately disastrous fashion.

The conclusion is inescapable: The human race is by nature nearsighted. We are smart enough to manipulate a planet, but not wise enough to steer clear of troublesome implications.

Every generation dreams anew. What were good ideas in 1950 too often make us cringe half a century later, simply because no one back then could foresee all the implications of their actions. Iron we must have, so we build an up-to-the-minute taconite factory to supply the ore. Twenty years later, we discover that the taconite process has coated the western bottom of Lake Superior with deadly asbestos. We cannot make our-selves wait; we will not exhaustively test every chemical, every process, every idea before we foist it on the natural world. Progress is impatient; everything must happen right now. Too often we discover too late that the price of such progress is dreadfully high.

We dream our dreams, just as the Iroquois, the Mormons, the immigrants dreamed theirs. Dreams of power, dreams of avarice, dreams of security. We even dream of doing good: saving the planet, saving the lakes, saving the lake trout. But everywhere, the foot-prints tell the tale of unforeseen disaster. The polluted rivers, the tainted harbors, the tumor-ridden fish, the eagles with twisted beaks, they are the footprints of our desire to shape the future. Presi-dent Clinton has recently proposed spending $80 million to clean up some of these footprints, including Waukegan Harbor and the Grand Calumet River. Presumably, the aim is to plan these cleanups thoroughly enough that the cure is not worse than the condition. We will see, in time.

We do so much, with such good intentions. Only later do we discover that our vision of the future is cloudy at best. We look backward with a sigh, and try to clean up the mess. And then we dream some more.

Robert Kuhn McGregor, an environmental historian at the University of Illinois at Springfield, is at work on a book about the Great Lakes. He is a frequent contributor to Illinois Issues. His most recent essay, "Speaking for the prairie," appeared in September.

Illinois Issues April 2000 | 40

|

Sam S. Manivong, Illinois Periodicals Online Coordinator Illinois Periodicals Online (IPO) is a digital imaging project at the Northern Illinois University Libraries funded by the Illinois State Library |