|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Political studies We get more information about the presidential candidates from paid ads and less from arm's-length political campaign coverage. That may not be as bad as it seems by John Carpenter Here it is. Decision time again in America.

We've all feverishly studied the presidential candidates and are poised to make another informed selection.

Leadership of the free world is at stake, so we've done our homework. We've heard their positions on the

major issues. We've sized up their answers to tough questions, looking for clues as to how they'll handle a

crisis. We've shushed everyone in the family room and carefully listened to their ads, weighing their

credibility and lining up their positions against our own. And we've considered their backgrounds, voting

records and affiliations, looked them in the eye as

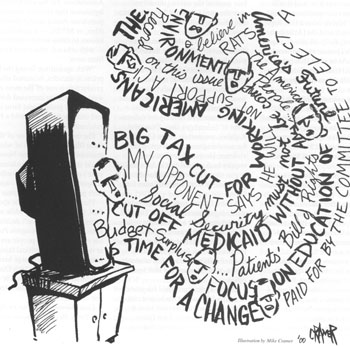

Illustration by Mike Cramer '00 26 | October 2000 Illinois Issues best we can to take their measure. Or maybe we haven't. Strike that. We haven't. The truth is, if history holds, most of us made up our minds long before the campaign began, based our decision on long-held party affiliations and general political leanings -- sort of a lifetime of political research. Political scholar Kathleen Hall Jamieson notes that the category of "early decider" in presidential elections ranges from a low of 54 percent in 1992 to a high of 79 percent in 1956. Veteran presidential political strategists use this rough rule of thumb: Each party's candidate claims about 40 percent of the vote, with the remaining 20 percent of the voters "in play'' in any one year. Still, even those of us who are longtime Republicans or Democrats like to think we go through some kind of decision-making process before we vote. And, certainly, the true "swing" voters in any race do. But the very pertinent question raised in two studies out this year is this: Where are we getting our information? The answer isn't pretty, at least on first reading. We increasingly get our information about presidential candidates from paid political advertising and less often from arm's-length political campaign coverage. But while the results of these studies make for nifty sound bites trumpeting the usurpation of political discourse by those with the deep pockets needed for political ads, the full story is far less simple and certainly less dire. Let's begin with a simple fact. Political advertising is up. This means the power of money is up, because advertising is expensive. And the prospect of free television air time for political candidates -- the Holy Grail for those who would level the economic playing field of politics -- is being thumped on the head by a $600 million club. That's the amount of money television stations are expected to take in this election cycle in return for running paid political ads. It's also a number the television industry's powerful lobbying arm, the National Association of Broadcasters, is feverishly trying to protect. (They protect it, of course, by giving money to politicians who are eager to accept the money so they can run more ads.) Illinois' own Tribune Company earned $25 million -- 2 percent of its revenue -- from political ads in 1998. It's no wonder Dennis Fitzsimmons, president of the broadcasting unit at the Trib, was quoted earlier this year as calling free-time proposals "not realistic.'' Meanwhile, most network news operations, where studies consistently show most Americans get their news, are covering politics less and less, meaning they are covering it worse and worse. (That's alarming in light of a finding by the Pew Research Center for People and the Press that 65 percent of Americans consider television their most trusted source of information.) Reformers had suggested that TV stations cover politics for at least five minutes a night for the 30 days leading up to an election. But a study by the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania found that the vast majority of stations surveyed in 11 cities in the 30 days leading up to presidential primaries this year aired an average of only 39 seconds of political coverage per night. Three of 19 monitored -- the study covered stations in New York and Los Angeles, as well as primary battlegrounds Iowa and New Hampshire -- devoted an average of about four minutes per night to politics. The rest could spare less than a minute. Nowhere was this more obvious than in coverage of this year's national party conventions. To be sure, they lacked the drama of olden times, when beefy cigar-chompers in smoke-filled halls tallied ballot after ballot into the wee hours before naming a standard bearer. But that drama is in the distant past. Loyola University political science professor Alan Gitelson argues the networks' claim that the lack of air time was because the conventions have become slick partisan packages is "absurd'' and a smokescreen for their abdication of civic duty. "This is their time to talk to us,'' Gitelson says of the major parties. "It is their time to talk to us about where they stand and who they are.'' If the conventions are too slick and disingenuous, Gitelson says, the public is perfectly capable of detecting that and allowing for it when they make their decision. Likewise, the public is able to do this with political ads, which he says are a 27 | October 2000 Illinois Issues "reasonably good forum in which individuals can learn about candidates.'' Indeed, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Center, argues in her new book Everything You Think You Know About Politics ... And Why You're Wrong that studies reveal a public well-equipped to evaluate political ads. While the cable television screaming heads and political scholars -- often one in the same -- decry negative advertising as if it were the plague, Jamieson argues that policy-oriented attack and contrast ads are often most informative, with contrast ads being the best. Attack ads, as the moniker suggests, are simply directed at an opponent. Contrast ads, meanwhile, cast the opponent in a negative light and build up the advertisee. "Our analysis showed that attack advertisements contained a greater percentage of policy words than did advocacy or contrast ads,'' Jamieson writes, adding that contrast ads are nevertheless "superior to those that simply attack'' because "the ads identify sponsoring candidates, which makes it possible for those who disapprove of the attack to hold the perpetrator accountable.'' And viewers do hold perpetrators accountable when they know who they are. Jamieson and her researchers played two versions of a hypothetical ad to a subject group. Most found the contrast version responsible, while most found the pure attack version irresponsible. Presumably, this would lead them to have a negative opinion of the person the ad wished them to have a positive opinion about. One problem, of course, is that many so-called "issue'' ads these days, whether pure attack or contrast, are from neither candidate. They are from special interest groups and there are a lot of them. By Labor Day this year, more than $114 million already had been spent on issue ads, according to Jamieson's group. And more than 40 percent of these ads were pure attack, coming from such well-known groups as the National Rifle Association and the Sierra Club, as well as those with more nebulous names, including the Traditional Values Coalition and the Committee for Good Common Sense. "Because issue advocacy ads are not subject to disclosure requirements, the press and public do not necessarily know who is funding the campaign or how much is being spent,'' Jamieson said in a statement earlier this year announcing the group's findings. "At the same time, funders can camouflage their actual agenda behind an innocuous group label, making it difficult for the public to assess the group's motives and credibility.'' Steve Brown, press secretary for Illinois House Speaker (and state Democratic Party chairman) Michael Madigan, agrees ads are on the rise and that "there has been a continuing shrinkage in news media interest in campaigns.'' This is unfortunate, Brown says, because positive media coverage is still far more effective than good advertising, indicating that media reports still hold sway with voters. The problem is that the television media have cut back coverage so much that they may have crossed the line from not doing as much good to having a negative impact by linking coverage too much to polling data. Consider the example of 1996. While no one is suggesting Bob Dole had much chance against Bill Clinton in 1996, that campaign is worth noting. Jamieson, wondering whether strategic, poll-oriented political coverage becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, notes that "with a single exception, the major polls dramatically underestimated Dole's likely percent of the vote." "In the campaign's final days, major media polls had Clinton defeating Dole by margins much higher than his eventual eight-point victory. One, a CBS/The New York Times poll, gave Clinton an 18-point advantage. Had reporters known that the likely vote was much closer than the polls indicated, would [issue] coverage have increased and strategic [horse-race] coverage of Dole decreased, and with these changes, would Dole's prospects have changed?'' As an aside, Jamieson notes that Clinton, in 1996, ran far more attack ads than Dole, though the taciturn Dole was perceived as the attacker in the campaign. Even the presidential debates -- by any measure one of the best chances to evaluate candidates -- are covered in the context of who won and who lost rather than what was said and what it could mean for the country, though Jamieson says debates remain one of the most widely used tools for voters to gather information about candidates. Newspapers are not immune to this criticism, of course. They can be just as attracted to the drama of the horse race as the networks. But just as CNN does a better job of political coverage thanks mainly to the amount of time it can give to stories, so too do the national dailies have the advantage of space and context. It should be said, too, that the Pew center has come up with another discouraging statistic: Only 15 percent of Americans actually go through the effort of looking for campaign news; 83 percent typically come across such information by happenstance. The flip side of this gloomy picture, of course, is that the increasingly fragmented media world is a candy shop for political junkies. Voters with computers are mouse clicks and literally seconds away from Web sites crammed with useful information about candidates and their views. And voters with cable can get both C-Spans on television, allowing them to fall asleep on the couch to a George W. Bush stump speech in an Elks lodge in Oklahoma, or to an Al Gore town meeting in upstate Pennsylvania. The bottom line is this: Ads may be crowding out news, but the situation is far from hopeless. Though good, substantive news may no longer be abundant on the mainstream television news stations, it's there in spades on cable networks and on the Internet, not to mention in the major national newspapers. So relax. And vote. John Carpenter is a free-lance writer and former Chicago Sun-Times and Daily Herald reporter. 28 | October 2000 Illinois Issues

|