|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

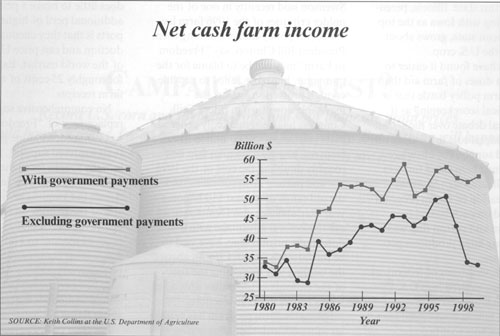

In that morally improving book Silas Marner, often force-fed to schoolchildren, author George Eliot observes that "nothing is so good as it seems beforehand." It's one of those admonitions, easily ignored but mockingly self-evident in hindsight, that might be embroidered and framed (as people of another age were fond of doing) by agricultural forecasters and policy-makers. Hanging that insight on a few walls in the nation's capital might prompt some humility as we head into a fifth year under the federal "Freedom to Farm" law that deregulated agriculture after six decades of federal acreage-limiting schemes. Conceived in 1996 during the halcyon days of high market prices, the law was promoted as the best route to farm prosperity by enabling farmers to supply the hungers of an increasingly affluent world. Federal farm subsidies were set at a few billion dollars a year, about two-thirds of past levels, and farmers gained broad power to switch from crop to crop to pursue profits. Reality, sadly, has not lived up to expectations, confounding the dominant theory that for 15 years has steadily reduced the federal role in agriculture and given greater sway to the free market to determine financial success. Economic turmoil in East Asia, Latin America and Russia in the mid-1990s took the edge off the appetite for U.S. farm exports, while a rare sustained run of good weather built up a global grain glut. The record-large U.S. corn and soybean crops forecast for this fall seem sure to bring a fourth year of sour domestic grain prices and renewed demands to rewrite the farm law long before it expires in 2002. "Obviously, you're talking about very depressed farm income levels," says Illinois Farm Bureau President Ron Warfield of Gibson City. True, were it not for the billions of dollars in farm bailouts approved by Congress since late 1998. That's an important 32 . October 2000 Illinois Issues www.uis.edu/~ilissues distinction in this state. Illinois, perennially competing with Iowa as the top corn and soybean state, grows about 17 percent of the U.S. crop. Lawmakers have found it easier to ladle out extra doses of farm aid than to resolve a farm policy battle that is as much political scorekeeping as it is philosophical debate over the appropriate federal role in assuring an adequate food supply. Populists say government must help small farmers survive, as well, although farm supports since creation of the ag program have been paid on each bushel or pound of grain and cotton that was grown, meaning large producers get the biggest share. In any event, vast sums of federal dollars are being poured into U.S. agriculture. This year, farmers will collect several billion in so-called loan deficiency payments that become available when market prices fall below the minimum prices determined by the federal government. On top of that comes $5.47 billion in annual subsidies guaranteed under the 1996 farm law and $7.1 billion in a farm bailout approved by Congress to further shield growers from low prices. When a smattering of money from conservation programs and crop insurance is added, farmers will see a record $22.7 billion in direct government payments this year, “stunning amounts” of spending, according to Keith Collins, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s chief economist. Without this year’s cash deluge, equal to nearly $11,000 for each of America’s 2.1 million farms, Collins calculates net cash farm income, a widely used estimate to gauge the financial health of agriculture, would be slightly lower than during the agricultural hard times of the mid-1980s, remembered as the last big shakeout. Instead, farm income has run at near-record levels of $55 billion to $57 billion a year, a level obscured by the noisy complaints of activist farm groups and “Freedom to Farm” critics who argue widespread suffering and low prices. “‘Freedom to Farm’ has reduced the viability of family farmers,” National Farmers Union President Leland Swenson said recently in one of the milder critiques of the 1996 farm law. Federal policy-makers, among them President Bill Clinton, say “Freedom to Farm” may not be to blame for the grain glut, but it has failed to provide enough protection against the inevitable downturn in prices. Still, Congress has been markedly generous in its response — $21.7 billion in three farm rescue packages since late 1998, roughly doubling the cost of the 1996 law and putting farm subsidies back in the old range of at least $10 billion a year. Republicans and Democrats, an eye to electoral advantage with a potentially pivotal bloc, have vied to be the farmer’s friend. Clinton abetted the bidding war by vetoing the first of the bailouts as too paltry only a few weeks before the 1998 elections. Fixing the farm program has proven far more difficult than diagnosing its shortcomings. As House Agriculture Committee Chairman Larry Combest said after a dozen hearings across the country earlier this year, “We didn’t find a clear consensus on how we should change federal farm policy.” For one thing, farmers have embraced a fundamental feature of the 1996 law, the “planting flexibility” that allows them to move from crop to crop without jeopardizing their farm subsidies, so any change in law will have to retain that provision. There is little interest in returning to the old system that often required farmers to set aside a portion of their land to qualify for crop subsidies. Higher crop support rates, the favorite nostrum of farm populists, quickly have become hugely expensive to the government and taxpayers — intolerable even with today’s federal surplus, unless they are accompanied by limits on how much farmers are allowed to grow or sell. Crop supports create a minimum price that is obtained through government loans that take a farmer’s crop as collateral. In the old days, farmers could forfeit the crop and keep the money if prices were low. Nowadays, they can pocket the difference between the loan rate and their selling price. It prevents the government from owning huge, price-depressing inventories of grain but does little to brake a price fall. An additional peril of higher crop sup-ports is that they encourage overpro-duction and can price U.S. goods out of the world market. Exports account for roughly 25 cents of each dollar in farm receipts. No comprehensive suggestion for a replacement of “Freedom to Farm” has surfaced, let alone gained more than scattered support. Democrats initially fought for higher crop supports but this year largely let the debate in Congress revolve around the size of the bailout. In the final weeks before the election, they are using the taunt “Freedom to Fail” to win over disgruntled farmers. And Democratic presidential nominee Al Gore routinely criticizes the 1996 law as seriously flawed without being overly specific about fixing it. For their part, Republicans, who sponsored “Freedom to Farm,” regard the bailouts as preferable to changing a law they see as the best way to position relentlessly productive U.S. farmers to benefit from food demand that will grow more rapidly overseas than in the stable U.S. market. Like Democrats, they are willing to look at alterations that would mean more money for farmers when prices are low. “It’s hard for me to see a better alternative out there that’s workable politically and other ways,” says Bob Peterson, leader of a farm and business coalition that was an early “Freedom to Farm” supporter. “The hard answer is we have to be patient and have faith in markets, that they will work.” In such a highly charged political environment, even a commonly suggested farm-law “fix,” creation of a “counter-cyclical” mechanism to increase farm support spending automatically when prices slump and reduce them during good times, remains an abstraction. To some extent, Bob Stallman, the president of the American Farm Bureau Federation, said in late summer, there has been a canny decision to wait until lawmakers are ready to act. A worthy idea can be chewed to death if supporters are too specific too early. www.uis.edu/~ilissues Illinois Issues October 2000 * 33 Net cash farm income  A sketchily outlined Clinton proposal, for example, to funnel up to $3.1 billion to family-size farms to bring crop revenue to 92 percent of the five-year average died quietly last spring. “I don’t believe there’s anyone who knows where ag policy is headed,” says Scott Irwin, a professor in the Agriculture & Consumer Economics Department at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. “Freedom to Farm” might survive, he says, because it is “everybody’s second-best alternative.” Practicalities could channel Congress toward limited revisions in farm policy. Writing a full-spectrum farm law can require a year or two of work, to the virtual exclusion of other initiatives. With only two years left in “Freedom to Farm,” there is little time left for fundamental change. So, despite dissatisfaction with repeated financial bailouts, “Freedom to Farm” could become the longest-lasting farm law in two decades. Without a consensus on broad-scale changes, lawmakers are more likely to concentrate on complaints that federal price supports favor soybeans over corn and wheat, think about devoting more funding to environmental provisions of the farm program, test the waters for targeting federal aid on small- and medium-size farms — an approach forcibly raised 20 years ago by then-Agriculture Secretary Bob Bergland — or limit the amount of money big operators collect. The current limit of $115,000 in federal subsidies can be doubled through receipts from two affiliated farm operations or circumvented entirely through so-called commodity certificates from the agriculture department. Farmers who are nearing the limit on subsidies can use the certificates to redeem crop loans from the government. “There certainly has been discussion ... and will continue to be” among farmers about payment limits and targeting benefits, Warfield says. He says he’s optimistic about farm prosperity in the long term because attention is being paid to boosting demand for crops by opening overseas markets and making more use of ethanol. Nonetheless, gargantuan harvests and a further softening in prices this fall could force dramatic action, despite the many reasons to expect smaller-scale action. Since midsummer, longtime agricultural analyst John Schnittker has warned of “the train wreck of extreme surpluses now building” in U.S. grain bins and argues the next president may need “to go to Congress on an emergency basis ... for temporary acreage-idling authority” to reduce crop output. That would be similar to the Payment In Kind programs under former-President Ronald Reagan that paid farmers not to grow. And Tom Buis of the National Farmers Union says he believes patience with the 1996 law will expire with the elections. “I think it’s next year, definitely,” he says, for rewriting “Freedom to Farm,” although Congress has resisted that chore in the past three years. As writer Damon Runyon, king of 1920s wise-guy argot, memorably opined, the race is not always to the swift or the battle to the strong, but that’s the way to bet it. . Chuck Abbott, who counts himself as part of the agricultural diaspora, is a commodities correspondent for Reuters in Washington, D.C. He has covered U.S. food and farm policy full time since 1988 and writes an occasional column on agriculture policy. He won the top award of the North American Agricultural Journalists in 1998 for contributions to agricultural reporting. 34 . October 2000 Illinois Issues www.uis.edu/~ilissues

|