|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

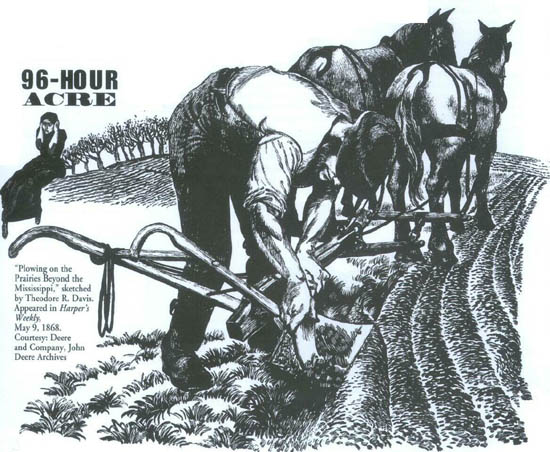

The Impact of Hiram M. Drache Historical Research and Narrative As Earth's population increased, technology was required to increase food production. Having observed that crops were more productive where the soil was loosened, people reasoned that the soil needed to be tilled before seeding. By the middle of the nineteenth century, a strong man using a modern steel spade still took an estimated ninety-six hours to till an acre of land. Obviously, some form of plow was needed. The first plows, dating to 4,000 B.C., were basically pointed sticks pulled through the soil. In all likelihood women were yoked to the plow while a man or men guided it. Humanity's inherent reluctance to change meant that improvements to the plow came slowly. The pace was particularly slow because everything agricultural was considered divine, and "any improvements in ancient processes" was "discouraged as impious" (Power and the Plow). But eventually a new plow evolved—the forked tree branch with one end of the fork around the horns of the oxen and the short end in the ground with another fork as a handle for guiding. Everyone marveled at how

2

easily that slid through the ground in contrast to the pointed stick. About 3,000 B.C. the Egyptians added a broader triangular share that turned a wider furrow. About the eleventh century B.C. the Israelites were using iron for their shares and coulters. Next, an iron plate and a moldboard that lifted the soil was added. Then came a pin to regulate the depth of plowing. Then a wedge to move the earth and redeposit it in broken pieces. As the population grew, more people moved from the cradle of western civilization into Europe. By the 1600s farmers in the Low Countries and near Cologne possessed a few plows. It required a great deal of power to plow the heavy, wet, sticky soils of that northwestern European area. To reduce the power needed, the Dutch developed an iron-covered moldboard that twisted and turned aside the sod as it was lifted from the furrow. When Europeans arrived in North America, they quickly realized that to survive they had to pursue systematic agriculture. Local units of government frequently offered a bounty to plow owners to keep their plows in good condition to do work for the town. In 1631 Massachusetts Bay Colony had only 37 plows. By 1648 Virginia Colony, the other leading area of population, had 150 plows. Plows were few in number for they were costly and the animal power needed to pull them was limited. Technology had to be improved so that plows might become more cost effective. In 1731 Englishman Jethro Tull improved the plow by adding a knife to slice the sod away from the earth below. In the mid-1780s Robert Ransome, of Ipswich, England, patented a cast-iron plowshare. In 1803 he patented case-hardening or "chilling the shares." This resulted in the share blade being sharpened as it slid through the soil, which greatly improved the plow's efficiency. By 1819 the improved cast-iron plow was widely used in England. Thomas Jefferson, minister to France from 1784 to 1789, had observed plowing and noted the difficulty that the French farmers had getting the plow to scour. He reasoned that there were two problems: the soil stuck to the wooden moldboard and that the moldboard needed to be designed to turn the soil as it was being lifted. In 1793 Jefferson derived the mathematical formula for the moldboard and proposed that the moldboard should be of cast iron. He also suggested that several moldboards could be mounted on a single plow frame. This was a major discovery. However, cast iron was avoided because many believed that it was poisonous to the soil. But in 1797 Charles Newbold, of New Jersey, patented a cast-iron plow. Finally in 1818 Jefferson's ideas about the mathematical design were implemented

3

when Gideon Davis built a plow using his formula. In England, Jethro Wood developed a three-piece cast-iron plow with interchangeable parts. The moldboard was one piece, the share that cut the furrow was the second, and the third was the landside that guided the plow. Wood's greatest contribution to the plow was the interchangeability of all parts. But the soil still stuck to the moldboard. As farmers moved west and encountered heavier and stickier soils, the problem intensified. Someone discovered that high-grade steel would scour in heavy soil. In 1833 John Lane, an Illinois blacksmith, cut three lengths of steel from an old saw and fastened two to the moldboard and another to the share. This worked quite effectively, but Lane did not apply for a patent. This set the stage for John Deere. John Deere was born February 7,1804, at Rutland, Vermont, to William R. and Sarah (Yates) Deere, the fifth of six children. At age seventeen Deere apprenticed himself to a blacksmith for a stipend of thirty dollars a year plus room and board, clothes, and instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic. His apprenticeship ended in 1825 and he immediately went into the blacksmithing trade. On January 28, 1827, he married Demarius Lamb. By 1836 the Deeres had four children, Demarius was pregnant with the fifth, and John was faced with bankruptcy. Deere sold his blacksmith shop to his father-in-law, left the proceeds of the sale to Demarius, and headed for Illinois. In September, Deere arrived in Chicago with his blacksmith tools and $73.73. He continued on to the newly settled village of Grand Detour, Illinois, on the edge of the frontier. There were no blacksmiths for forty miles, so Deere had work at once. In 1837 he built a twenty-six-by-thirty-one-foot shop on rented land and began construction on a wood-frame house. Deere learned that farmers were experiencing the same challenge with tilling the soil as in Vermont, but in Illinois the soil was much heavier and stickier and covered with tall prairie grass. Breaking the prairie sod required a heavy plow powered by as many as eight yoke of oxen. This was costly, so most settlers chose to plow the land themselves with a smaller plow and their own horses or oxen. This was slow, hard work requiring the constant use of paddles to scrape the sticky soil off the moldboard. Farmers came to Deere hoping that he could help them. While visiting Leonard Andrus's sawmill, Deere noticed a broken steel saw. Deere asked if he could have it. Back in his shop Deere chiseled the teeth off and then heated and shaped it with a hammer. The saw blade was polished from its use at the sawmill. There are conflicting reports, but it appears that Deere's first plows used the saw blade steel for the share and smoothly ground wrought iron for the moldboard. Wrought iron could be welded and would reasonably scour in heavy soil. Deere's first plow, finished in 1837, worked better than any previous plow. In 1838 he built two more plows, one of which was sold to Joseph Brieton, who farmed just south of Grand Detour. That implement was later discovered and purchased by Charles Deere and is on display at the Smithsonian Institution. By May 24,1839, Deere had built three more plows, and before the year was over he had produced a total of ten. The plows sold for ten to twelve dollars each, which was a considerable purchase for a farmer of that day. In 1840 Deere produced forty plows; in 1841, seventy-five; in 1842, one hundred; and in 1843, four hundred. That does not seem like a great number by today's standards, but in addition to the shortage of funds, farmers were still skeptical about the durability and usability of the plow. Deere had to establish a reputation as a manufacturer of superior plows. However, according to historian Wayne G. Broehl, Jr.: "It was largely his [Deere's] ability to dramatize these products and get them into the hands of his customer... that made him a success."

Deere's "Improved Clipper" with rolling coulter.

Appeared in Country Gentlemen August 20, 1857. Courtesy: Deere and Company, John Deere Archives

4 The demand for broken saw blades for plow shares exceeded the existing supply, and plow makers looked elsewhere for satisfactory steel. Deere purchased steel from Sheffield, England, at a cost of $300 per ton, but it still required polishing for proper scouring. In 1844 he secured improved steel produced by Lyon Sharb & Company of St. Louis, which he used for the plow share, but he continued using wrought iron for the moldboard. In 1846 his search for steel similar to what was made in Sheffield ended when Jones and Quigg Steel Works of Pittsburgh produced the first slab of cast plow steel made in the United States. This was far superior to any other steel on the market. In 1843 the railroad bypassed Grand Detour, and Deere decided it was a doomed town. He established a partnership with John Gould and Robert Tate and moved to Moline. This was a much better farming community, near unlimited supplies of coal and on the Mississippi, which provided water power and lower cost of distribution. Under the new partnership Deere was free to do sales work and marketing. A new building was completed August 31,1848, and they produced 700 plows by the end of the year. The plant was expanded just in time, for in the first five months of 1849 more than 1,200 plows were ordered. Manufacturing innovations were being rapidly introduced, and Deere, always a leader in adapting the latest technology, purchased several new machines. With the new equipment, a work force of sixteen produced 2,136 plows that year. In 1850 the firm began handling the Seymour grain drill. This was significant because it was Deere's first step into expanding beyond being strictly a plow company. In 1853 Charles Deere, aged sixteen, joined his father. He was relatively well educated and quickly climbed the rungs of the leadership ladder. For the next fifty-four years Charles provided the firm with the entrepreneurial leadership necessary to propel it to the front ranks of farm machinery manufacturers. Each year orders continued to increase. Production kept up with the demand, and by 1857, 10,000 plows were made. Unfortunately, the Panic of 1857 made collections difficult. In 1858 John Deere turned the leadership over to Charles.

According to historian Wayne G. Broehl,

Jr.: He [Deere] was energetic and purposeful, moving forward despite ownership squabbles, business ups and downs, marketing battles, and countless other problems. He was not.. .a major inventor .. .[but he was] an adapter and marketing innovator. He was not a financier.. .But he did have a knack for organization, an abiding concern for quality, and a feeling for the role of the agricultural equipment industry in America's growth that made him a preeminent producer and distributor of agricultural machinery. During the trying times of 1858, Joseph Fawkes, developer of a steam-powered plow, teamed up with Deere. In 1859 the two won the gold medal at the Illinois State Fair. The seventy employees were kept busy producing 15,000 plows a year. Census data indicated that the company was in the top six of the 420 plow manufacturers in the nation.

In 1863 the company added a second non-plow implement when it began production of the Hawkeye riding cultivator made under a patent arrangement with inventor Robert W. Furnas. This was the first implement produced by Deere that was adapted to riding. In 1864 wheels were mounted to a plow to create the single-bottom sulky. Finally in 1867 Jefferson's suggestion that more than one moldboard be mounted on a frame was heeded, and the two-bottom gang made its appearance. A farmer using a walking plow could till about one to one-and-one-half acres a day, but with a gang he could do about five-and-one-half acres. In 1886 Charles Deere assumed the presidency of the company and remained in that position until his death in 1907. After Charles assumed the leadership, his father was free to do what he liked best—tinkering and innovating. He made improvements to the plow, which resulted in the first three patents by anyone in the company. On August 15, 1868, the business was incorporated as Deere and Company. During the next two decades manufacturing was grouped into five categories: walking and wheeled plows, cultivators, harrows, drills and planters, and wagons and buggies. The expansion came at a good time, for the development of transcontinental railroads greatly improved selling opportunities. In 1873 (the year John Deere was elected mayor of Moline) plow production reached 60,000, and despite the panic and recession that lasted until 1876, plow sales increased by about 5,000 a year. Collections continued to be a problem, so Deere and Company adopted a program of financing retail customers. This innovation created strong ties with the farmers. Deere and Company reached its first million dollar sales year in 1878-1879 and hit two million prior to 1900. Net assets grew even more rapidly, exceeding $1 million in fiscal 1878-1879, doubling by fiscal 1887-1888, and surpassing $3 million in the 1895-1896 fiscal year. A marketing organization was developed that included opening five branch sales offices and warehouses. In 1911 the company took a major leap when it acquired six implement makers to become a full-line farm equipment manufacturer. Its growth virtually exploded after that.

5

In 1913, to keep up with the capital requirements, Deere and Company became a publicly held company. (If a person had acquired ten shares of stock in 1913 and held them to November 17, 1995, they would have owned over 4,812 shares in addition to the earnings from dividends.) With capital raised through the sale of stock, Deere made its single most important acquisition in the machinery line when it purchased the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company and got into the tractor business. By 1963 Deere and Company was the world's largest farm equipment manufacturer. The company had an industrial equipment line and had added the John Deere Credit Company which became one of the twenty-five largest finance companies in the nation. Next, it expanded into the lawn and ground-care business and the insurance business. In 1985 it founded Heritage National Health Plan, which became one of the twenty largest multi-state health management organizations in the country. Development in the late 1980s of the golf and turf equipment line was followed by the purchase of Homelite—hand-held and walk-behind products company. In 1995 yield-mapping precision farming systems were introduced to keep the company in step with the fast changing high-tech agriculture. What has all the above meant to the state of Illinois, which is generally ranked as the fourth or fifth largest agricultural state in the nation? In the late 1990s the state's 76,000 farms generated over $9 billion in cash receipts, or averaging about 7 percent of all the nation's farm produce. In Illinois production agriculture has 120,000 workers—about two percent of the state's labor force—to market about 2.8 percent of Illinois' gross domestic product. Deere and Company has 37,000 employees worldwide of which 7,300 work in Illinois. In addition, the eighty-two independent John Deere dealers in the state employ another 1,476 individuals. In 1997 the combined payroll of company and dealerships was $440,800,000—a figure 440 times greater than the total volume of sales in 1878-1879 or the total company payroll of 1913-1914. Worldwide, the 37,000 Deere employees produced nearly $12 billion in agricultural, construction, commercial, and consumer equipment plus generating another $1.9 billion in finance, interest, insurance premiums, investment, and other income. The little twenty-six-by-thirty-one-foot blacksmith shop has been replaced by a series of factories throughout the world. In the United States and Canada alone Deere has twenty-one factory locations totaling 29.4 million square feet of floor space, an area greater than one mile by one mile. Nearly 27,000 people are employed in those factories and offices in addition to 3,250 independent John Deere dealers in the two nations who employ about another 50,000. In addition, the company has factories in foreign lands and a dealer network located in 110 other countries of the world. The state of Illinois is fortunate to have a combine harvester plant and foundry in East Moline, a factory for planting equipment and another for hydraulic cylinders in Moline, a parts distribution center at Milan, and offices for John Deere Credit, Inc. at Bloomington. Corporate Headquarters, along with Industrial Sales Office, Deere Marketing Services, Deere Catalog Company, John Deere Merchandise, National Sales, Power Systems Group, John Deere Credit Company, John Deere Insurance Group, and John Deere Casualty Insurance Company—all of which make up the

Woodcut from a Deere advertisement, 1854. Courtesy. Deere and Company, John Deere Archives

6

cornerstone of the worldwide empire—are located at Moline. Nearly everything that the above divisions do is somehow involved to make American and Illinois agriculture the most dynamic in history. Much of the success can be attributed to the development of the plow and all the agricultural implements that have followed. Remember, that to till an acre of land with a spade required 96 hours (5,760 minutes); to plow an acre with a yoke of oxen and a crude wooden plow took twenty-four hours (1,440 minutes); with a steel plow such as John Deere developed took five to eight hours (300 to 480 minutes); but in 1998, a 425-horsepower John Deere 9400 four-wheel-drive pulling a fifteen-bottom plow tilled an acre every 3.2 minutes. Never in history has an acre of land been moldboard plowed with less physical effort by the plowman. Never has the soil been better tilled, nor has it produced more. Today the work is performed 1,800 times faster than the person who spaded the acre, and 122 times faster than with the plow of the mid-1800s. Everyone who enjoys the abundant supply of inexpensive food should be grateful for John Deere and his plow. Click Here for Curriculum Materials

7

|

|

|