|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Richard Allen Morton Municipal governments have always been responsible for some degree of public convenience, and they have assumed increasing responsibility for services as cities have grown larger and more complex. The city of Chicago has been no different. By the late nineteenth century, that rapidly growing metropolis had extended the responsibility of its government to provide fire and police protection, sewers, and water to city residents. Those changes had occurred without significant controversy, and indeed the Great Fire of 1871 made the growth of governmental oversight seem even more compelling. However, extending Chicago's city government to address the growing problem of public transportation in the 1900s became the defining issue of its time and place. The prospect of municipal ownership and operation enraged conservatives, polarized ideologically the city's and state's developing progressive movement, and dominated politics for years. In the course

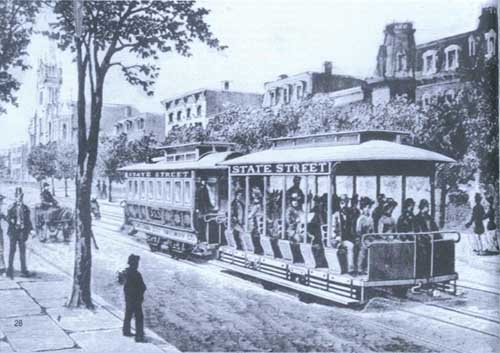

28 of this battle over "municipal socialism," issues emerged that address both the nature of reform in Illinois and America, as well as the relationship of government and society. Those issues remain viable today. Much of the transportation tangle that beset turn-of-the-century Chicago found its source in the city's tremendous growth. Population had increased (according to the federal census) from 298,977 in 1870 to 1,698,575 in 1900, while the area of the municipality had grown from 35.7565 square miles in 1869 to 190.6380 in 1899. Streetcars were both a cause and an effect of the expansion. Horse-drawn cars were put into service in Chicago in 1859, and nearly twenty-five years later horse-drawn cable cars were added to the urban transit mix. And with the introduction in 1890 of the trolley—the electrical cable car-Chicago enjoyed an unprecedented level of transportation efficiency. By 1906 electricity had replaced all other forms of locomotion. In addition, a system of elevated railroads began operating in 1892. Technological advance, however, did not guarantee good service, and by the turn of the century there was a general consensus in the city that Chicago suffered from the worse public transportation in the world. There was also broad agreement that much of the problem stemmed from governmental ambiguity and misdirection; city and state authorities had been simply too overwhelmed, and according to some, were corrupt and/or incompetent to take things into hand. The city's first misfortune was its division based upon the two branches of the Chicago River in 1853 for franchise purposes by the state legislature. From the beginning a unified traction system was impossible, and it was difficult to enforce improvements. In 1865 the legislature again made things more complex by enacting the Ninety-nine Year Act as an amendment to the charters of the city's three largest streetcar companies. Obviously serving the interest of the companies, the law extended from twenty to ninety-nine years their rights to the use of the streets. The 1870 state constitution further confused things by requiring a municipality's consent for all such franchises. Since the city had never agreed to the extensions, it was unclear whether they were valid. In 1883 the city avoided contesting the issue by extending for twenty years the franchises of two of the affected companies whose original charters had expired.

The lack of clear governmental supervision exacerbated a situation that many characterized as predatory capitalism at its worse. Public transportation was big business, with massive profits, and fierce competition. At one time the city counted sixteen traction companies with rights to its streets. Although that number would decline to nine, then four, and by 1930 to just one, it was the public who generally suffered for the lack of cooperation among its public transportation providers. In the first place, before 1907 there were, as a rule, no transfers, which meant that one could conceivably pay as many as three or four fares to cross the city or to get to work, a considerable expense for a workingman earning less than a thousand dollars a year. Fatal accidents were regular events. Cars were typically dirty and unheated. Even worse, schedules were not usually coordinated nor always followed. Adding to the growing discontent was resentment that a few well-known men seemed to be making fortunes from the sufferings of the citizenry—and corrupting the people's government in the process. The most widely vilified of these was Charles Yerkes, the controlling officer of the West Chicago Railway and the North Chicago Railway companies. He was behind the notorious Humphrey Bill of 1897, which would have extended franchises to fifty years had it not been narrowly defeated in the General Assembly The following year, Yerkes and his cohorts successfully lobbied the legislature to pass the Allen Law, which gave the city the choice of disadvantageous twenty or fifty-year franchises. The city council in turn was persuaded by the powerful traction interests to extend all charters to fifty years. Public outrage followed, and Mayor Carter H. Harrison II vetoed the measure. A mob formed outside of city hall to assure that his veto was upheld by the city council, which, not surprisingly, it did. Yerkes subsequently consolidated his holdings into the Chicago Consolidated Traction Company, which he promptly sold. He then left for England, where he gained fame and additional fortune by building the London Underground. Such was the political environment in which municipal ownership was promoted. However, its emergence can only be fully understood in the context of the more general mood for progressive reform, which grew increasing powerful in the last decade of the 29

nineteenth century. By that point, many Americans were finding it difficult to recognize their country. What once had been a rural and agricultural society culturally based upon basic Protestant mores, had become urban, industrial, and increasingly affected by new Catholic, Orthodox, and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. A new prosperity had been achieved (though at the cost of cycles of boom and bust), but the twin pressures of a new entrepreneurial group of "robber barons" and a restive working class seemed to threaten the essential middle-class character of American life. Accordingly, it was primarily the middle class that demanded reform that would draw from the values of the past and the new efficiency of the present. However, while reform was clearly in the air by 1900, there were important differences among its advocates both in terms of goals and methods. The most fundamental distinction among the progressives who first appeared in the cities of the midwest, including Chicago, was between "structural" and "social" reformers. The structural reformers, or "goo goos" (for good government), were generally upper middle class and Republican. Their chief interest was to introduce honesty and business-like efficiency into city government. Believers in individualism, the Protestant work ethic, and private enterprise, they strove for a municipal authority that, once cleansed of corruption, would be smaller in size and function and would guarantee lower taxes and enforcement of public order and private morality. Outside Chicago, some called for "restructuring" (hence the label) of municipal government upon business lines through the introduction of a professional city manager or the replacement of the traditional mayor and city council with elected commissioners. In the Windy City, structural reformers worked through such organizations as the Citizens Association, the Civic Federation, and the Chicago Bureau of Public Efficiency. Their greatest success came in the formation of the Municipal Voters League in 1905, which by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century had done much to eliminate the "Gray Wolves," aldermen thought to be corrupt, from the city council. Social reformers, on the other hand, were less concerned about making government "clean" than they were about transforming it into the agency of the people's welfare. Therefore they were highly supportive of the direct democracy of the initiative, referendum, and recall, regulation of the work place, and— the most emotional issue—the municipal ownership and operation of public utilities. In Chicago, the social reformers included a wide range of people—including liberal judges and lawyers, labor leaders, and middle-class social activists—all of whom tended to congregate in the Democratic party. There was also considerable communication among social reformers of different states and cities, and those in Chicago were in regular contact with such figures as Mayor Tom L. Johnson of Cleveland, Ohio, and Mayor Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones of Toledo. In addition, there was a general mutual sympathy between Chicago's social reformers and the Great Commoner, William Jennings Bryan. Municipal ownership may have been the central ideological goal of the social reformers of Chicago, but by 1900 it had also attracted broader support. It was not only routinely endorsed by both major parties, but it inspired former Governor John Altgeld to make an independent (unsuccessful) bid for the mayor's office in 1900. Two years later, it was the focus of a short-lived Public Ownership Party. In both 1902 and 1904 the voters in advisory referenda overwhelmingly voted their endorsement of the idea, and this in itself guaranteed some measure of public acceptance among mainstream politicians. In the latter year, the cause was immeasurably boosted by the passage by the state legislature of the Mueller Law, which provided for municipal ownership in Chicago with the approval of three-fifths of the voters. Moreover, under the new law two-thirds could approve the issuance of bonds for finance. However, the support of the political establishment was more apparent than real. Mayor Harrison, the Democratic mayor who had been reelected in 1903 promising to implement the Muller Law, emerged from negotiations with the traction companies in the following year with the "Tentative Ordinance." This provided for twenty-year franchises, improved service, and the possibility that the city might begin acquiring traction property in thirteen years. Although the city's structural reformers deemed it a practical solution, the uproar was immediate, and Harrison's explanations were in vain. With seeming spontaneity the anger over the ordinance in the mayor's party coalesced around a young social reformist judge, Edward Fitzsimons Dunne. Dunne was almost unique among his peers in being successful politically while managing to avoid for the most part the factional wars that characterized Chicago politics. Moreover, he enjoyed a level of respect within the Democratic party unmatched by any other genuine social reformer in the city. He was born to Irish immigrants in 1850 in Peoria, Illinois, where his father alternated between radical Irish politics (he was said to have returned to the old country repeatedly to work for Irish independence) and a series of successful businesses. Initially educated in the public schools, young "Eddy" Dunne was then sent to Trinity University in Dublin, Ireland, where among his classmates was the writer 30

Oscar Wilde. Forced to return before graduation due to financial reverses at home, he and his family then moved to Chicago where he obtained a law degree from the Union College of Law. He soon became the protege of Judge Murray Tuley, an important judicial Democrat, and it was largely through his intervention that the young Dunne was nominated and elected in 1892 to fill a vacancy on the Circuit Court of Cook County

On the bench Dunne acquired a reputation for justice and charity. He also became active among the city's Irish community, and was frequently a featured speaker at Democratic and Irish gatherings. He also became closely associated with Chicago's social reformers and counted among his friends and political allies. William Jennings Bryan, Clarence Darrow, and Henry Demarest Lloyd. As early as 1898, he began speaking passionately for the municipal ownership and operation of the traction systems, echoing the frequent social reformist attacks against corporate power in the United States in general. In 1901, he toured European traction systems, and in 1904, Mayor Harrison had appointed him to help lobby for the Mueller law. Following the announcement of the "Tentative Ordinance," he openly broke with the mayor in a dramatic speech before the Fortschrift Turner Society on September 4 of that year by calling for immediate municipal ownership. So powerful was the speech and its reflection of a growing mood among the public that there were immediate expressions of interest in Dunne as a possible mayor, and he found himself applauded at restaurants and elsewhere. At first reluctant, he at last consented to enter the race in response to a public call for his candidacy by Judge Tuley. There was no real contest. Harrison's chief factional rivals, former mayor John Hopkins and his partner Roger C. Sullivan, came out for Dunne, the mayor withdrew, and at the city Democratic convention he was nominated by acclamation. Next he faced the Republican, John Maynard Harlan, a man with considerable experience in the traction question in his own right. However, the Republican campaigned in vain, and Dunne won by a margin of 161,189 votes to 138,671 (the largest margin of victory for any mayor up to that time). At the annual Jefferson's Day Banquet held not long after his inauguration on April 11, 1905, the new mayor was feted as the harbinger of a new era of social reform in Chicago. Attending and speaking his praises were such social reformist luminaries as William Jennings Bryan, Mayor Tom L. Johnson, Clarence Darrow, and Judge Tuley. At the very least, it seemed that municipal ownership of the traction systems was assured. However, in the first of his two years as mayor, Edward F. Dunne was confounded by events shaped by the city's political establishment (including most especially the structural reformers) and his own miscalculations. Dunnes' most important mistake was coming into office without a clear plan for the initiation of immediate municipal ownership. The voters had, it was true, ratified the Mueller Law in the recent election, but neither the new mayor nor his advisors was clear as to how exactly to bring about its implementation. What natural impetus there might have been was dissipated by the outbreak of a violent teamster's strike that lasted weeks. Finally at the suggestion of Mayor Johnson of Cleveland (who had achieved municipal ownership in his city and who repeatedly visited Chicago and toured its trolley lines with Dunne), he wired 31

the bemused municipal authorities of Glasgow, Scotland, to send their traction expert, James Dalrymple, who arrived in early June. He inspected conditions and then left. The mayor mysteriously withheld the Scot's report from public perusal for over a year. Now left to his own resources, Dunne next conferred behind closed doors with his Special Traction Counsel, Clarence Darrow, as well as Mayor Johnson and his traction experts. In late June, he presented his scheme for immediate municipal ownership. It offered two alternatives. The City Plan provided for the immediate acquisition and operation of the street railways through the issuance of Mueller bonds. This was feasible, the mayor admitted, only if the Ninety-nine Year law was overturned in court, which it seemed it might, and if, under the Mueller statute, three-fifths of the voters approved municipal operation (ownership only required a simple majority). Instead, the mayor recommended the "Contract Plan" as satisfying both the need for municipal ownership and the sound business principles demanded by the city's structural reformers. A semipublic holding company was to be created that would immediately take over the ownership and operation of the street railways beginning with the hundred miles or so immediately available to the city under a recent court ruling after repairing and improving them. The company would then sell the traction lines to the city at cost plus a reasonable rate of interest. Enthusiasm was high among the social reformers, but the city council was not impressed. The measures were formally introduced on July 5, and then sent to the Committee on Public Transportation, which sat on them. Meanwhile the committee began its own negotiations with the traction companies. Only in September, and then only because of the mayor's pressure, did they even debate the administration's schemes. Most skeptical were those aldermen most closely identified with the Municipal Voter's League and with structural reformism. One could not believe that Mueller bonds could assure adequate financing, while others were concerned that the end result would be a chaos that would be an even further disservice to the public. Still others questioned whether the city could efficiently administer a business as complex as the street railways. Accordingly, the committee voted by a margin of eight to four to defer further discussion until the companies had the chance to make counterproposals. This effectively prevented any further action since it stopped the measures from going to the full council. The mayor's attempt, in his capacity as presiding officer of the council, to order the consideration of his plan only resulted in lopsided defeats. This in turn brought about the highly publicized resignation of his Special Traction Counsel, Clarence Darrow (who continued as the city's lawyer in its efforts to overturn the Ninety-nine Year Law). Mayor Dunne was not silent in his frustration. Always a champion of the popular mandate, he began an intense schedule of public speeches first around the city and then throughout the nation. His themes were consistent; only municipal ownership could bring effective public transportation, and his opponents were either misguided or nefarious. At one speech in Denver, he went further and attacked the "capitalists," identified for his purposes as the House of Morgan, and "the swell clubs of the rich" whose influence was thwarting the people's repeatedly expressed wish in Chicago. When subsequently pressed, he conceded that he was "not a socialist" in the Marxist sense, but that he believed in "municipal socialism": that "public property [the streets] should be utilized and operated by the public" without "special privileges" to any "private person."

His passion might have been for nothing; his supporters routinely attempted to call up one or both of the plans out of committee, and the rest of the council just as routinely voted them down. Suddenly on January 16, 1906, in what the mayor called "a flash of lightning," the council's "Gray Wolves" figuratively crossed over to the mayor's side and voted not only for consideration but also for the passage of the city plan. Consternation prevailed. Even Dunne's floor leader, alderman (and future mayor) William Dever, was reluctant to accept the support of those thought to be corrupt, and who probably voted for the plan as a signal to the traction companies to keep the money coming. The mayor, however, was sanguine, and signatures were soon collected among the voters to place the measure on the ballot in the upcoming elections in accordance with the Mueller Law.

At last it seemed things were going the mayor's way. In early March, the United States Supreme Court finally overturned the notorious Ninety-nine Year Act and thus greatly enhanced the city's ability to take control of the traction lines. The news was so good that Mayor Dunne used the occasion to release the long-suppressed Dalrymple report. It proved that the Scottish expert was not as optimistic about municipal ownership in Chicago as the mayor, arguing that the city was not sufficiently developed for it to work. The clear implication was that the Windy City's political culture would render the efficient ownership and operation of something as complex as public transportation impossible. Nonetheless, the mayor and his

32 supporters were jubilantly optimistic as they approached the April elections. The elections were an intense disappointment. The conflict of the previous year had worn down public commitment. To be sure, all three municipal ownership and operation propositions had obtained a majority of votes. However, where a simple majority was sufficient for the city to initiate municipal ownership, the margin of just over 50 percent for operation and financing through Mueller bonds fell far short of the three-fifths majority required by law. The elections were broadly interpreted as an unmitigated defeat, and clearly the mayor's major asset, the assumption of popular support, had been shown to be now of limited value. Some thought this would end things and that Dunne would allow the municipal ownership idea to fade, and that he might even resign. This was to grossly underestimate both the man and his commitment. Within days he announced the appointment of a new Special Traction Counsel, Walter L. Fisher. Fisher was closely identified with the city's structural reformers, and he had helped found the Municipal Voter's League and the City Club. Between 1887 and 1888 he was the equivalent of Special Traction Counsel for Mayor John A. Roche, and in 1905 he served on a commission sponsored by the National Civic Federation to investigate public utilities in the United States and Europe. He had voted for Harlan in 1905. Later in 1909 President William Howard Taft would appoint him Secretary of the Interior, and in 1910 he would become a member of the Chicago Bureau of Public Efficiency. In short, he was a prominent structural reformer and a Republican, and Dunne in choosing him was making a clear effort for broader support among the city's progressives. Next the mayor issued the so-called "Werno letter"—an open communication to Charles Werno, the chair of the Committee on Public Transportation. Showing Fisher's influence, it called for new negotiations with the traction companies. Meanwhile, the companies were to continue operations on the condition that they begin immediate improvements until the city could arrange for purchase based upon a fair assessment of tangible and intangible worth. Until then they were to split all profits evenly with the city. The Werno letter was a success, and virtually all concerned applauded its reasonableness. Negotiations began in an unaccustomed atmosphere of general harmony and briefly it seemed that a final settlement would be quickly forthcoming. Perhaps inevitably, this did not last, and soon the talks degenerated into a battle in which every minor point became a major point of contention. At last after eight months of arduous negotiation, Fisher in December 1906 presented his hard-won agreement to the mayor and the city. On the whole, the agreement represented a major step forward in the city's control of public transportation. Its major provisions included: 1) twenty-year franchises for the three major companies, with the city having the right of purchase during the last five years of the charters with six months notification; 2) complete rehabilitation of the lines at an estimated cost of $40 million; 3) compensation to the city for the use of the streets at a rate of 55 percent of net profits; and 4) the creation of a board of engineers with veto powers to regulate the companies. The mayor was exuberant in his praise of his Special Traction Counsel and his hard-won agreement. Briefly it seemed that the festering traction problem was on the brink of resolution. But it wasn't, within weeks the mayor had made a complete turnaround, first demanding that the agreement be placed on the ballot and then turning against the settlement itself. He now claimed it was fatally flawed in its mechanisms for determining the valuation of the lines. Certainly Mayor Dunne was correct in claiming that it did not provide for immediate municipal ownership. However, it is difficult to imagine

that he really expected that to emerge from negotiations overseen by a man like Fisher. Instead, this mystifying turnabout seems to have had its source in political realities. The mayor's social reformist supporters were definitely not supportive of the Fisher agreement, and the evidence suggests that they stampeded him into demanding a referendum on the issue. Moreover, there was the definite threat of a new group called the Independent League created by William Randolph Hearst in cities where he had newspapers (including Chicago). This group denounced the settlement and threatened to run a mayoral candidate of its own in support of immediate municipal ownership. Accordingly, Dunne vetoed the Fisher settlement, which the city council promptly overrode. Fisher then resigned, only to be appointed by the council as its Special Traction Counsel. Thus it was that Mayor Dunne went forth to do battle for reelection against a traction solution that originated in his own administration. The irony of the situation was not lost on the Republicans, who nominated Fred Busse as their mayoral candidate in the April 1907 elections. Busse was a machine politician who had served as state assemblyman and state senator. He was now postmaster of Chicago and presided over his own "federal faction" of the local Republican party. He was a man with no record at all on the traction issue and whose career stood in stark contrast to the kind of idealistic reformism that Dunne represented. Smelling blood, the Republicans had with unaccustomed unanimity rallied behind the postmaster. Seemingly, the mayor brought to the contest important assets, including most especially his own incumbency, the strength of his character, and the support of a group of almost fanatical social reformists like Margaret Halley of the Chicago Federation of Teachers and the members of the Independent League. Dunne campaigned without sparing himself, speaking as much as eight times a day. The social reformers rallied union support, and Hearst's newspapers the Journal and the American proclaimed Dunne's candidacy a holy crusade. In the end, however, Dunne's supporters undercut his chances. Many Chicagoans had been uncomfortable with the early reliance upon Cleveland's Mayor Tom L. Johnson, and even larger numbers were distrustful of the apparent influence of William Randolph Hearst upon the mayor. Similarly, the actions of Dunne's appointees to the school board (who included Jane Addams) on behalf of the Chicago Federation of Teachers had led to chaotic and controversial results (including the denial of raises to teachers who had passed promotional examinations) that undercut public confidence. Most important, of course, was the mayor's stand on the Fisher settlement. The voters had, it was true, repeatedly supported the concept of immediate municipal ownership in advisory referenda. Moreover, they had shown their willingness to vote 34 Mueller bond issues to implement immediate municipal ownership. However, the issue was always efficient and inexpensive transportation. This seemed promised by the Fisher agreement, and the population could not understand the mayor's opposition. Dunne and his followers did their best to resurrect the popular crusading spirit of two years earlier. Massive rallies were held, and the mayor spoke until he was hoarse, but it was clear that public support was diminishing. The Republicans, moreover, seemed to have all the cards. All of the city's newspapers with the exception of those belonging to Hearst backed Busse, and the Republican candidate greatly enhanced his chances by managing to be in a serious accident during the campaign. This excused him from speaking, a blessing since he was a notoriously poor speaker, and it restrained Dunne and company from making personal attacks lest they appear ungracious! Even more portentous was that the regular Democrats were showing little sign of enthusiasm for their mayor. They had no use for a man who passed over loyal Democrats in favor of his personal circle of reformers and social activists for city jobs. Just as importantly, the mayor looked like a sure loser, which more than any other thing rendered him ineligible for any real effort on the part of the professionals of his party. Near the end of the campaign, one old political hand suggested that the solution was to spread a few thousand dollars among the "boys" of the river wards. Dunne declined. Not surprisingly, Fred Busse won the election with 164,839 or 49% of the vote to Dunne's 151,823 or 45 percent of the total. Making the rejection of the mayor and his program even clearer was the ratification by the even larger margin of 56% of the Fisher settlement. Ironically the mayor had carried almost as many wards as two years earlier, but the turnouts there declined as much as 30%. Thus it was that municipal socialism failed in Chicago between 1905 and 1907. Dunne nearly won renomination for the mayor in 1911, and a year later he was elected as Illinois' most progressive governor. However, he never again sought office upon a platform for immediate municipal ownership. In 1924 Dunne's council floorleader, William Dever, became mayor, promising city ownership and operation of the street railways. Dunne, however, opposed his plan, and it failed at approval by the voters. In 1930, in a city reeling from the Depression, an early form of the Chicago Transit Authority was approved, but it was not implemented until after World War II, and it only offered limited municipal ownership and operation. Genuine municipal ownership could very possibly have been achieved by the Dunne administration. However, it is problematic whether the city could have owned and operated the complex traction business efficiently and without corruption. To be sure, success on the traction issue might well have assured the reelection of Mayor Dunne, and there is no doubt that he would have done his best to make the Chicago system a model operation. But with the benefit of historical hindsight we know that in 1915 the city's most notorious chief executive, William Hale Thompson, was elected to the first of three four-year terms. It is difficult to imagine that Thompson (a man later associated with Al Capone) or someone like him would have been an effective and incorruptible caretaker of the people's public transportation lines. In the end, James Dalrymple, Dunne's Scottish expert, was probably right in concluding that the Windy City's political culture made municipal ownership impractical. What is even clearer, is that the issue of municipal socialism as it relates to the role and size of government remains viable almost a hundred years later. In 1905, as today the issues of how far the government should be inserted into the life of the community was and

35

is the subject of contention. On one side are those, like the social reformers, who see government as the ultimate social arbitrator and engineer, and on the other are those, like the structural reformers, who fear higher taxes, the perceived threats to individual liberty, and the inefficiency implicit in governmental growth. In the end neither extreme has prevailed. Reflecting the American genius for compromise, the middle course of expanded governmental regulation emerged triumphant in 1907 and remains the dominant theme in government's relationship to society. Beyond the immediate issues of municipal socialism, the fight for immediate municipal ownership of the traction lines also speaks about the nature of reform and reformers in the American political culture. It underscores that those seeking change do not always share the same agenda and are often each other's worst enemies. Clearly the opposition by structural reformers both within and without the city council was a decisive factor in the outcome of events. Even more importantly it demonstrated that reformers, while excellent at raising issues and stimulating debate, are not always adept implementing their ideas. Dunne was among the most politically experienced of the social reformist leaders, yet he and his supporters made some very elementary political mistakes. Not the least was their failure to have a definite plan for immediate municipal ownership before the 1905 election. With a plan, the momentum of the electoral victory might well have quickly translated into success with the city council. Instead the Dunne administration delayed, giving its opponents time to reorganize and regroup. Mayor Dunne also failed because he did not initially work within the preexisting power structure, preferring instead to bring in outside experts and advisors. More politicking and exchanging favors with "the boys" might also have brought success. By 1906, he seems to have realized this, and his appointment of Walter Fisher was a masterstroke. It in turn, however, was vitiated by the demands for ideological conformity by his social reformist allies, which undercut what could have well been a crowning accomplishment—and one that would have brought his reelection and the possibility of greater reform. A further lesson to be derived from Chicago's traction battle was that it revealed a fundamental fact of American government and society which is that even in our most representative of systems the people's delegates do not always do what their constituencies demands. Despite the results of two referenda and an overwhelming victory for a mayoral candidate calling for municipal ownership, the city council simply declined to go along on the grounds that the scheme was unworkable. Even more importantly the voters did not retaliate against their leaders. In the end, the principle of leadership in the determination of governmental policy took precedent over simple democratic expression, as it continues to do in our society to this day. The Chicago traction fight of 1905 and 1907 was but one episode in the larger history of Chicago, the Progressive era, and of reform itself. Nonetheless, its details are significant in revealing the interaction of reform and politics as American society wrestled with the challenges of industrialization and urbanization near the turn of the century What is truly remarkable, however, is that in the end it speaks to us not just of that time and place, but of enduring realities still present in our community today. Click here for Curriculum Materials 36 |

|

|