|

Bogged Down

in Northern Illinois

A bog is a swamp is a fen is a marshy or is it?

STORY BY GARY THOMAS

PHOTOS BY ADELE HODDE

Most people don't know what a bog is. Many think a bog is a swamp, is a fen, is a marsh. Until a few months ago, you could put me in that category. And when I was asked to write a story about Volo Bog, my question was probably similar to what a lot of people ask: "Why would anyone want to visit a bog?"

Here are a couple of reasons. Volo Bog isn't just a bog. It's a quaking bog. And it's a quaking bog with an open water center. It is truly one of the more fascinating places you'll find in Illinois.

Let's begin with a disclaimer. Volo Bog is geared a little differently than other DNR sites. This isn't a state park or recreation area. Volo Bog is a natural area—a place dedicated to environmental discovery.

"Don't come here looking for conventional recreation opportunities," said Greg Behm, site superintendent. "This park is more for environmental activities and passive recreation. We don't have fishing or playgrounds or camping, and there's only a limited bow hunting season by permit only. But if you have a healthy curiosity about the environment, you might want to give Volo Bog a look."

Perhaps the best way to tell you about Volo Bog is to begin with a geologic history of the site starting about 15,000 years ago when the last glacier—known as the Wisconsin glacier— was retreating north out of what would become Illinois. As the glacier moved north, debris was left behind, including giant boulders, gravel, sand and huge hunks of ice the size of small cities that broke off as the glacier melted. The rocks and dirt formed the landscape, and the ice created huge craters. As the climate warmed, the ice melted to form natural lakes, and 10,000 years ago, Volo Bog was a lake of about 40 acres.

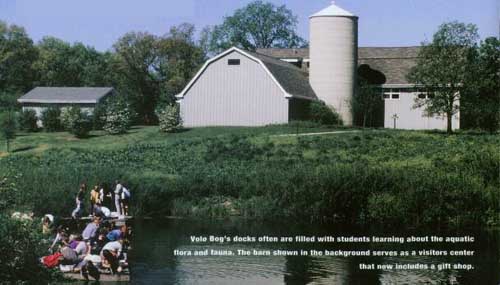

Volo Bog's docks are often filled with students learning about the aquatic flora and fauna. The barn shown in the background serves as a visitors center that includes a gift shop.

|

|

8 OutdoorIllinois

The boardwalk allows curious visitors to explore the site without harming the fragile ecosystem.

|

|

|

But while other lakes created in a similar fashion had inlets and outlets creating replenishing water and current, Volo had steep banks and poor drainage—a land-locked waterway with stagnant water.

In the natural world, a lake begins filling from sedimentation and eventually will deteriorate into a bog or fen, then become a marsh or a swamp, and finally dry land. Its whole purpose, it seems, is to lose its water and become land again. It's called natural succession.

And there really is a difference between a bog and a fen and a swamp and a marsh. A bog is a wetland that has no feeder inlets and no outlets. It lives on rainwater and snow melt. A fen is a wetland with a mineral-rich supply of water. Swamps and marshes have feeder inlets and outlets. Swamps are dominated by trees and marshes by herbaceous vegetation.

Actually, Volo Bog does include a very minor inlet, so from a strict technical standpoint, it's not a true bog.

But the feeder is so minor that the area is often called a bog.

What's interesting about a bog is that it appears to be solid land right out to the open water. There are ferns, thick-leaved plants and large trees growing there. But the so-called land is anything but. It is layers of floating organic material, mostly sphagnum moss, that didn't decompose well because the water is both acidic and stagnant. A bog begins small at the edge of the lake and thickens into layers, until finally it is capable of supporting plants, shrubs and eventually tamarack trees that can grow upwards of 60 feet.

Because water in bogs tends to be acidic, only specialized plants live there. These plants usually are those with leathery leaves that conserve water. At Volo, you'll find unusual ferns, poison sumac, leatherleaf, rare orchids and carnivorous pitcher plants that eat insects. In fact, more than two dozen rare, threatened or endangered plants can be found there. You'll also find rare birds, such as the endangered yellow-headed blackbird, American bittern, veery, sandhill cranes and white-winged crossbills.

The floating mat is made up mostly of sphagnum moss. It works its way ever so slowly toward the center of the lake, until it finally connects and there no longer is an open water center.

While it looks firm, keep in mind this mass is floating. If you step onto it, you'll think you're walking on a waterbed. In fact, the weight of a person can cause the plants to shake, which is where we get the term "quaking bog."

|

June 2002 9

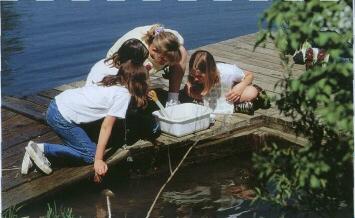

| Interpreter Stacy Milter shows off some of the aquatic invertebrates to three Big Hollow School students.

|

Tamarack trees, a northern species rare to Illinois, have a horizontal root system that helps keep the mat together. Their roots don't go below the mat. In fact, these trees cannot live where it is too wet.

"Once the mat becomes too thick and grounds itself to the bottom of the bog, tamarack trees die," said Stacy Miller, site interpreter. "They can float on top of the mat, but they cannot tolerate having their root systems submerged for extended periods. So dead tamarack trees are pretty good indicators of where the floating bog ends and land begins."

After the Wisconsin glacier retreated, it left behind numerous lakes that became bogs. They are plentiful in Minnesota and Wisconsin, but northern Illinois is about as far south as they occur, and less than a dozen still exist in Illinois. Volo Bog just happens to be the best of these bogs, and the only one in Illinois that still includes an open water center.

Because of this, Volo Bog displays all stages of vegetative succession, from open water lake to upland forest. The open water in the center of Volo Bog represents the remains of the lake formed by the retreating glacier. Next is the bog itself—floating sphagnum moss with rare plants and trees. As you continue outward, you will come to shrub swamp and marsh areas. And once you get to dry land, you are at the edge of the original lake basin.

So essentially, Volo is a lake is a bog is a fen is a swamp is a marsh, kind of like I said earlier.

How long will open water remain in Volo Bog? No one is saying, and there is no succession time table. But don't hold your breath.

"The last glacier left here about 11,000 years ago, and when it left, this became a lake," Miller said. "Succession has been going on a long time. Today there is less than an acre of open water left, so you can see how slowly it occurs."

Scientists believe succession has been going on about 6,000 years, and there is good reason to believe they're accurate. Miller said oxygen-poor, acidic water preserves items in the bog, so pollen grains and leaves deposited thousands of years ago are close to their original condition. By taking core samples, scientists know what the climate and vegetation was like in this part of the state for the past 6,000 years.

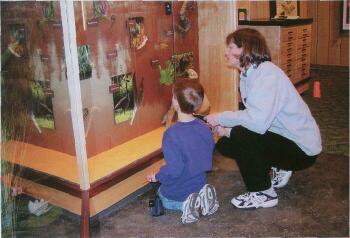

A tour of the bog begins in a renovated dairy barn that serves as the park office and visitors center. Built in the early 1900s, the barn underwent renovation in the mid-1990s and now includes a gift shop and accessible restrooms. The silo alongside the barn houses an elevator to transport disabled visitors to the second floor, where they'll find a reference library, a hands-on discovery area and newly installed exhibits, including a small bridge which simulates what it would feel like to walk on the floating mass.

Most of the outside tour will be on a boardwalk that goes through the marsh and bog to the open water. What's unique about the boardwalk is that parts of it have been sinking for years. When it sinks to the water level, another one is built on top of the old. The first one was built in the 1920s, and the current one is layer number seven. There are six below it.

Volo Bog came to the attention of scientists 75 years ago, when a North-

|

The visitors center houses a hands-on discovery area and exhibits featuring the geologic history of plants and animals in the bog.

|

|

|

10 OutdoorIllinois

The picnic area offers a shady spot to rest, eat and enjoy the scenery.

|

western University professor pointed out its importance. Nothing was done to preserve the site until 1958, however, when The Nature Conservancy bought 47 acres and turned it over to the University of Illinois. Nothing more was done there until 1969, when a developer attempted to get the area around the bog zoned for a commercial residential complex.

In 1970, the Attorney General took steps to ensure the residential development wouldn't damage the bog. That same year, the University of Illinois transferred its acreage to the Department of Conservation (now the Department of Natural Resources), and the site was dedicated as a state nature preserve. Three years later, the state bought the developer's 150 acres of land and began proceedings to purchase another 450 acres. That same year, the site was designated a national natural landmark by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Since then, nearly 600 additional acres have been purchased to buffer and protect the area from development, including 330 acres during the past five years, bringing the site to about 1,200 acres in size. Volo now includes several marsh areas, a number of prairie restoration areas, two other bogs and some woodland areas. Included is an old barn that's home to the largest nursery colony of little brown bats found on public lands.

"Twenty-five years ago, the biggest threat we had was development," Behm said. "Chicago was growing this direction, and we're close to the Chain of Lakes, a major recreation area, so people were trying to buy property here to build homes. We now own enough land around the bog so development is no longer a threat."

The biggest concern today, according to Behm, is invasive species. Buckthorn was the exotic invasive plant that was a threat a few years ago, but while that threat has been eliminated, today there is a more formidable one.

"We started seeing purple loosestrife here about 12 years ago, and it has been spreading," Behm said. "We've tried numerous things to reduce or eradicate it, including the release of European beetles said to feed on these plants. The loosestrife is still here, but we have it in check for now."

Another threat is the extension of Route 53, which was proposed a number of years ago, but hasn't been acted on lately. That route was engineered to go through the property.

Volo Bog is fortunate to have a "Friends of Volo Bog" organization with about 250 members, and also a volunteer network with about 60 active members that help with prairie burns, plantings and tours. The site staff and volunteers offer numerous fun educational programs throughout the year for people of all ages, including bog tours, birding, astronomy, prairie walks, insect safaris, bat programs and story telling.

Volo Bog also has nearly five additional miles of trails beginning near the visitors center and offering scenic views for hikers and crosscountry skiers.

There's also a small picnic area located near the visitors center, though no fire ring is available. Since ground fires are not allowed, visitors must bring their own grill if they want to cook.

As fascinating as Volo Bog is, I'll admit that it's not for everyone. In fact, only about 60,000 visitors go there each year, and this despite the fact that it is located within 50 miles of more than 8 million people, and within 10 minutes of the Chain of Lakes, Illinois' busiest outdoor summer playground.

But if you're looking for a quiet place in the midst of commotion, a land filled with rolling hills, unusual sights and a truly unique outdoor adventure, you really should give Volo Bog State Natural Area a look.

|

Information you can use

Address: Volo Bog State Natural Area, 28478 W. Brandenburg Road, Ingleside, IL 60041.

Telephone: (815) 344-1294. Directions: Located in Lake County 5 miles south of Fox Lake, 1 1/4 miles off Route 59.

Hours: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Memorial Day through Labor Day. Reduced hours during the fall, winter and early spring.

Tours: Scheduled site tours take place 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. on Saturdays and Sunday,

or can be arranged in advance for groups of 10 or more. You can also pick up a trail guide and tour the bog on your own.

|

|

Gary Thomas is the former editor of Outdoorlllinois.

|

June 2002 11

|