|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

The Duck Scholarship

STORY BY JOE MCFARLAND

One cold day between hunting seasons, Harvey Pitt looked skyward and faced the truth about those ducks. There wouldn't be any ducks where he was going. And he sure couldn't take them along when he died. As Pitt lay recovering in a Springfield hospital bed, watching an electronic heart monitor confirm he was still alive, the aging duck hunter realized the rules of material possessions hadn't changed since 1927. That was the year he was born, which meant he had lived a full life already. But even before that near-fatal heart attack in November 2000, Pitt long understood how life and death work. Nobody slips into the afterlife with souvenirs collected on earth. Not even a truckload of antique waterfowl decoys. Pitt thought anxiously about those decoys—the Ward Brothers, the Perdews, the prized Masons—every last, precious one of them. He envisioned how his cherished waterfowl collection would remain after he died: treasures meticulously arranged on the very shelves where he'd left them, all going nowhere. Unless he did something about it. So Harvey Pitt had to make a decision. Nobody would be around to inherit his collection. "My wife Mickey and I have no heirs," the 75-year-old waterfowler said, speaking in a hoarse voice of acceptance. "When we're gone, that's it." For those who don't recognize the Illinois waterfowler's name, Pitt is owner of one of the finest collections of antique decoys in North America. It all began in 1960, when the art of wooden decoys was fading fast in the post-World War II age of plastic. When Pitt began saving decoys, he had no intention of amassing a fortune. Yet it all began to add up. To get down to business, the collection is worth a lot of money, simple as that. It's "a substantial" figure, as Pitt describes it. Inevitably, anyone near such a collection eventually begins to count fingers, estimating value. Everything has a price. So many rare decoys, so many, many dollars. The value of the collection looms over all considerations. The sale of Pitt's decoys and related waterfowl collectibles would mean a significant, six-figure inheritance to someone. So Pitt needed to make arrangements. He had to decide, finally, what would

2 OutdoorIllinois

become of everything he owned—those hundreds of rare, antique waterfowl decoys he'd accumulated during the past 40 years. Who would get them? Who should? Should he open a one-of-a-kind museum, some perpetual repository for one of the finest waterfowl collections anywhere? If he gave it all away, was there anyone on earth deserving of such a fortune? Selling the collection was an easy option. It was always an option. But not really. Calling it quits and cashing it in meant giving up the majority of his existence while he was still alive. And he was still alive. Even as he lay in that hospital bed three days after the doctors brought him back to life, old decoys remained Pitt's identity. He lived to collect decoys and he lived to study and preserve the history of waterfowling in America. In addition to the hundreds of rare and expensive waterfowl decoys he'd accumulated, along with the waterfowl mounts (Pitt is also a taxidermist), hand-carved calls, artifacts and knick-knacks, he also saved reference books. Waterfowl books. Every book he could find about the history of ducks and geese was up on his shelf, waiting for anyone who wanted to learn about this increasingly distant history to merely stop by and ask. Knowledge always meant something to Pitt. The possession of knowledge outweighed mere possessions—after all, what good is an old decoy sitting on a shelf unless the story behind it were understood? A lifelong student, an information-seeking historian of all things waterfowl, Pitt wanted to know everything. As a young man in 1952, he received his master of science degree at Southern Illinois University, devouring books and lectures. Before that, there was McKendree College near Belleville, where Pitt earned straight A's his senior year. He was ambitious, yet hungry, earning an education the hard way. In those days, money was scarce for a World War II veteran. "There wasn't a poorer student around when I went to McKendree," Pitt said, explaining how simply getting to class on $75 per month was a daily challenge. "Sometimes I'd hitchhike from my home in Mascoutah to Lebanon, about 20 miles round trip. If I was lucky, I'd be able to beg a ride. "You have to understand, there weren't any scholarships available for biology students when I was in college. If you were an outstanding athlete, there were plenty of athletic scholarships available. But nothing for biology students." Pitt never forgot the hardship of his college days, even as the comparative luxury of his present life permitted him to buy a single decoy worth thousands of dollars.

October 2002 3

Pitt's. true wealth—the wealth of knowledge—came at an expense greater than he believed anyone should have to endure. Getting an education shouldn't be a privilege for only those who could afford it, Pitt decided. So there was his answer. "When I was in that hospital, staring at that heart monitor, I decided what to do about the collection," Pitt recalls. "The day I came home, I told Mickey to call McKendree." This lifetime student realized there was, after all, a selfless solution to his mortal fate. His valuable collection could be sold to create an educational scholarship. It would be a McKendree scholarship—specifically for needy biology students. Pitt's 40-year accumulation of waterfowl rarities would be transformed into a posthumous gift to biology students who needed financial help. Any upstanding biology student at McKendree would be eligible. "The stipulations are few, only that this scholarship will be awarded to any deserving biological science student at McKendree, regardless of their faith, race or ethnic origin," Pitt says. "I will let the board of trustees decide specifically how it should be administered."

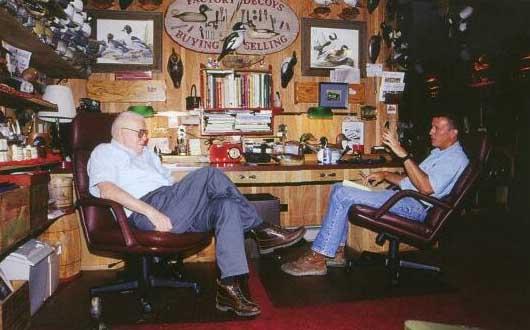

It would be more than a year, and another hospital stay, before the final papers were signed. Yet his mind was set. Always a man of his word, there would be no second-guessing what would become of the treasure of decoys. Upon the death of both Pitts, the collection will be transferred to McKendree College, then sold. So it was decided. It was finished in a sense, yet not finished. Pitt was still alive...and living meant collecting those beautiful decoys, just as he'd done for more than 40 years. There was also one other thing. In addition to saving old decoys, Pitt now manufactured a brand of his own. A trusted friend named Ed Dunham teamed up with Pitt a few years ago to create their personal line of authentic, hand-painted cedar ducks to preserve the folk art known as American waterfowl decoys. Pitt and Dunham's cottage industry partnership, P&D Decoys, was born.

OutdoorIllinois

True, plenty of artists and craft makers churn out novelty decoys. But these old warriors weren't interested in distorted representations of decoys. P&D decoys are meant for actual duck hunting, not the coffee table. "These are gunning decoys," Pitt insists while inspecting a pintail drake he's just finished painting. "I know a lot of them will never see water (collectors are snatching them up as fast as they're made with hundreds already on back order), but they're made to use." Between painting sessions, Pitt still negotiates deals for rare decoys he craves. His rules of business, as in life, remain fairness and honesty. "I tell people what their decoys are worth, and then I offer that price," Pitt explained, adding he never preys upon anyone who doesn't realize what they've got, even if the opportunity to make a steal is easy. "There's an old saying that you don't make a widow cry," Pitt said knowingly. College officials at McKendree, meanwhile, aren't waiting quietly for the eventual endowment. They've planned a show this month to honor the living man whose kindness will assist future, kindred biology students.

A homecoming exhibit of Pitt's collection—a portion of it—is set for the weekend of Oct. 18-19. Pitt and Dunham will be on hand to answer questions about decoys and waterfowl during the weekend and to mingle with students, faculty and alumni. "He holds McKendree very close to his heart," observes John Nonn, director of major gifts at McKendree, who proclaims Pitt's "sense of right and wrong" to be exemplary. "He is definitely a man of high character and moral structure." "He's an amazing guy," adds Jane Weingartner, director of planned giving for McKendree. "Harvey Pitt is a person who has such high integrity, he will always be an example to our students." Nonn is quick to note times have changed since Pitt was a hungry student at McKendree. It's considerably more expensive. And while there are finally scholarships available specifically for biology students (a total of two), a single semester's tuition now averages $7,100. Clearly, the duck scholarship will make a difference. "Harvey's gift will allow students to achieve goals that they might never achieve without financial assistance," Nonn said. "Obviously, he is a very generous man."

|

|

State Library |