|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Home | Search | Browse | About IPO | Staff | Links |

|

Kaskaskia Lures

Cloy Houser's love of fishing lured him into the business world. STORY BY TIM BAHR

Located in west-central Illinois, and 50 miles east of St. Louis, is Carlyle Lake, the largest manmade lake in the state. That lake, along with the nearby town of Centralia, provided the background for a small business venture that produced "Kaskaskia Lures." The business was not only an important piece of local history, but the story depicts a man's pursuit of the American dream. This adventure was comical at times, sad at others, but definitely a learning experience. This fisherman's tale is not a stretch of the imagination, but it will play on your emotions, and maybe have you reexamine the path to your own dream. It's the American way of life—anyone can have a dream and pursue it. For some, the goal is the most important accomplishment. For others, the journey is the satisfaction. For Cloy Houser, the journey was an education that provided rewards, and the goal evolved into the knowledge of how to accept disappointment. "I just got too old before I started thinking," remarked Houser, when asked about his experience. Cloy Everett Houser was born in August of 1919 at Centralia. In the 1940s, he fished Horseshoe Lake in southern Illinois. His favorite lure for that water was the Shannon Twin Spinner. In the 1950s, he worked in Lakeland, Florida, spending free time casting a Heddon River Runt on the shallow lakes and trolling a Millsite Daily Double on the deeper ones. Then he discovered worm fishing. "At that time, plastic worms were stiff as a lead pencil," Houser remarked. "My fishing buddy and I would wade out at night past the snakes into the open water. We used keel sinkers with our worms because bullet sinkers weren't around yet. We were all the time getting hung up and losing our tackle, but we caught nice fish." In the 1960s, Houser's employment took him to five other states, eventually landing him in Los Angeles. After his dad died, he decided he'd had enough of the concrete jungle of California and headed back to

16 OutdoorIllinois

Centralia, where he belonged and where there were three seasons: fishing, hunting and fishing. Houser's plan was to work a few more years before retirement and fish as much as possible. He had no intention of going into the lure business, even though he was playing around with several ideas about how to catch fish with artificial bait. At that time, Virgil Ward's Beetle Spin was the talk of the fishing world. Houser copied that spinner bait, but instead of a curly worm tail, he cut a straight tail lengthwise and came up with the current split tail. He and his friends had so much success with his "Split Tail Spin" that he decided to try and sell them locally.

Houser's friend. Harry Moore, made his own jigs and spinners and sold them under an untrademarked name, Kaskaskia Lures. Moore sold Houser the name and some supplies to get started. In 1967, Houser developed a spinner bait that had deer/squirrel hair for the skirt. His inspiration for this lure was the Shannon Twin Spin he had fished with years earlier. This bucktail bait was called the "Invader." It was a short-arm spinner bait with a jig head like most of the spinner baits of that time. A lot of the existing spinner baits had rubber/vinyl skirts, but Houser hand tied all his hair skirts. The biggest difference was the shape of the lead head. Most jig heads were rounded or blunt. Houser tapered his down to a point and streamlined the rest of the lead body to glide through the water smoother. The bait was field tested on Carlyle Lake and the Kaskaskia River. After his fishing buddies gave their approval that the bait was indeed effective, Houser put it on the market. The Houser Bait Company was off and running. Not only was the lure a success in the water, but it was also a hot item in the few bait stores that sold it.

In order to expand distribution of his two lures, Houser hired a factory rep for a sporting goods company and his brother, Wayner, became his partner, helping make lures. They hand tied all their skirts, a labor-intensive stage that slowed down production. Thus, as demand continued to rise, production remained slow. They couldn't keep up with orders. Reality hit the two brothers one day when a buyer from Central Hardware came to Centralia and wanted to place an order for several thousand "Invaders." Houser was shocked at the request. "I said, 'Well, mister, you may believe that I'm lying to you, but I ain't got nuthin' to sell. I'm out. I got one salesman, and he can sell more than we can produce,'" Houser recounted. Amazed at his success, but bewildered by the supply-demand ratio, Houser was embarrassed. He accomplished what he had set out to do, but nobody told him that success could also be overwhelming. In order to speed production, and without changing their flagship lure, Houser came up with a lead-head bait that had a vinyl skirt. The lure was called a "Dilly," after a fishing friend who had died.

December 2002 17

This new bait was also successful, but this time supply met demand. Of course, production time spent on the "Dilly" took time away from the production of the "Invader." Houser hired three elderly widows to paint jig heads for a penny apiece in their own homes. At this point in time, the business operated in a small building the brothers owned. They trademarked the names "Kaskaskia Lures," "Invader" and "Dilly." These were the only lures Houser had trademarked, and he never sought a patent for any bait. The excitement of producing fishing lures and having them sell so easily encouraged the Houser brothers to expand even further. This time they ventured into the worm business. They designed their own rubber worm and had 50,000 of them produced by a company in North Carolina. They then purchased a million worm hooks from Eagle Claw in Denver. The result was a No. 2 hook with long bucktail hair tied to it, followed by a nine-inch rubber worm. This long-haired bait was called a "Hippie Worm," named after the then present-day hippies. "Well, that thing took off like gang busters," Houser remarked. Once again, they couldn't keep up with demand, so they switched to a vinyl skirt and eliminated the bucktail.

With the addition of the new worm inventory, room was getting cramped. They attempted an assembly line means of production, but too many obstacles arose. As the Housers tried to increase output and solve problems, orders for product poured in and the backlog continued to rise. At one point, the brothers became frustrated and offered unsuccessfully to sell the business to a partnership. Baits designed in the 1970s were the "King Rattler," "Queen Rattler," "Bullet Spin" and "Bug Eyed Frog"— products that saved the business, at least temporarily. The brothers contracted with workshops at Centralia and Fairfield to pour and paint lead heads, assemble spinner harnesses and prepare peg-board packages. Production increased, but new problems arose. More equipment was required and constantly needed maintenance. Supplies had to be ordered in large quantities to supply both workshops. Rejects were common at the start, but the training paid off and steady production of good products resulted. One logical-sounding idea eventually ended the dream. The Centralia Sentinel published a catalog that contained pictures, sizes, colors and prices of the lures. Their salesman and Cloy Houser's son, who sold lures in Arizona under the Houser Bait Company name, distributed the catalogs. The orders streamed in. Sporting goods stores in Florida, Oklahoma and Ohio placed orders. The Housers then received a notarized letter from Canada containing an order for two million dollars of products and requesting exclusive rights for Kaskaskia Lures in Canada. "That deal was out of my league. I couldn't even talk to the man," recalled Houser. The brothers could not fill an order that size under the existing conditions. To further prove that things were getting out of hand, he turned down a request for a business ad in the Yellow Pages. "1 was afraid somebody would call and I wouldn't have anything to sell," he stated. "It may sound like a joke, but it was the truth." Tragic but true. In 1974 the brothers were out of room for expansion, had most of their money tied up in invoicing and still couldn't keep up with orders. "It got hectic and the business just got ahead of us," recalled Houser. He knew the financial officer at the bank 18 OutdoorIllinois

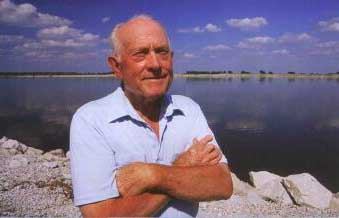

Along the shores of Carlyle Lake near his Keyesport home. Cloy Houser reminisces about his lure company. and asked for a small business loan for a building, machinery, employees and supplies. As the loan was being worked out, he began to see the enormity of the whole situation. "I was scared," he reminisced. "I told my brother, 'Wayner, we ain't no spring chickens. We are going to have to work like the devil for 10 years to get the business on stable ground and pay the bank back. Then our lives are gone; that's the end of us. Do we want to go into this?'" As the business limped along and they contemplated their options, the decision was made for them. Cloy Houser's wife was diagnosed with cancer and soon died. That was rough. He lost interest, not only in the lure business, but life in general. All he did was mourn.

"I had no desire to get in there and fight anymore," he said. So, he gave his part of the business to his brother and moved to Keyesport. His brother eventually sold the business to the state, which purchased it for workshops. Wayner Houser supervised the workshops for three years then retired. The state later sold the business. When I interviewed Houser, he compared his experience in the lure business to fighting a fish. "You reel and reel but the fish keeps on taking line. It's something you like to do, but every once in a while you would like to land that thing," he said. I came away with the feeling that he was disappointed with himself. He said he did not get to establish a business that was profitable and stable enough to stand on its own.

"I wish that I had started the business 20 years earlier. I would have taken the money the bank offered and produced the baits people wanted to buy," Houser commented. Houser closed our conversation saying, "We weren't big. But when you buy a half a million hooks at one time, you're not exactly little." Again, it's the American way of life. Anyone can have a dream, and if they work hard, they might achieve it. I believe Houser achieved his dream, but was confused on his goal. The journey was his goal; not success. He has lived his life for the sport he loves. And along the way, he's left some lures and memories of the Houser Bait Company.

December 2002 19 |

|

State Library |